Henrietta Lacks

Henrietta Lacks | |

|---|---|

Henrietta Lacks circa 1945–1951 | |

| Born | Loretta Pleasant August 1, 1920 |

| Died | October 4, 1951 (aged 31) |

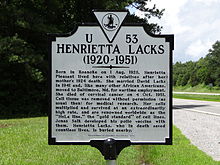

| Monuments | Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School; historical marker at Clover, Virginia |

| Occupation | Tobacco farmer |

| Spouse | David Lacks (1915–2002) |

| Children | Lawrence Lacks Elsie Lacks David "Sonny" Lacks, Jr. Deborah Lacks Pullum Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman (born Joseph Lacks) |

| Parent(s) | Eliza (1886–1924) and John Randall Pleasant I (1881–1969) |

Henrietta Lacks (August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951)[1] (sometimes erroneously called Henrietta Lakes, Helen Lane or Helen Larson) was an African-American woman who was the unwitting source of cells (from her cancerous tumor) which were cultured by George Otto Gey to create the first known human immortal cell line for medical research. This is now known as the HeLa cell line.[2]

Early life (1920–1940)

Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920,[1][3] in Roanoke, Virginia, to Eliza and Johnny Pleasant.[4] Her family is uncertain how her name changed from Loretta to Henrietta.[1] Eliza, her mother, died giving birth to her tenth child in 1924.[4] After the death of his wife, Henrietta's father felt unable to handle the children, so he took them all to Clover, Virginia, and distributed the children among relatives. The 4 year-old Henrietta, nicknamed Hennie, ended up with her grandfather, Tommy Lacks, in a two story log cabin that had been the slave quarters of her white great-grandfather's and great uncles' plantation.[1] She shared a room with her 9 year-old first cousin David "Day" Lacks (1915–2002).[1][4]

Later life (1941–1950)

In 1935, at the age of 14, Lacks gave birth to a son, Lawrence. In 1939, her daughter Elsie was born. On April 10, 1941 she married her first cousin, "Day" Lacks, who was the father of her children in Halifax County, Virginia.[1]

At the end of 1941, their cousin Fred Garrett convinced the couple to leave the tobacco farm and have Day work at Bethlehem Steel's Sparrow's Point steel mill. Soon, they moved— Lacks' husband first, then Lacks herself and two children—to Maryland. Day bought a house for the family with the money Garret gave him when he went overseas. Their house was on New Pittsburgh Avenue in Turner Station, now a part of Dundalk, Baltimore County, Maryland. This community was one of the largest[5][6] and one of the youngest[6] of the approximately forty African American communities in Baltimore County.

Lacks and her husband had three other children: David "Sonny" Jr. (b. 1947), Deborah (1949–2009), and Joseph (b. 1950, later changed name to Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman). Rahman, Lacks' last child, was born at Johns Hopkins Hospital in November 1950, just four and a half months before Henrietta was diagnosed with cancer.[1] At about the same time, and to Lacks' great distress, the couple placed Elsie, who was described by the family as "different", "deaf and dumb" in the Hospital for the Negro Insane, which was later renamed Crownsville Hospital Center.[1] Elsie died there in 1955.[1]

Diagnosis and death (1951)

On January 29, 1951, Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital because she felt a "knot" inside of her. She had told her cousins about the "knot"; they assumed correctly that she was pregnant. But after giving birth to her fifth child, Joseph, Henrietta started bleeding abnormally and profusely. Her local doctor tested her for syphilis, which came back negative, and referred her to Johns Hopkins.

Johns Hopkins was their only choice for a hospital since it was the only one near them that treated black patients. Howard Jones, her new doctor, examined Henrietta and the lump in her cervix. He cut off a small part of the tumor and sent it to the pathology lab. Soon after, Lacks learned she had a malignant epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix.

Lacks was treated with radium tube inserts, which were sewn in place. After several days in place, the tubes were removed and she was discharged from Johns Hopkins with instructions to return for X-ray treatments as a follow-up. During her radiation treatments for the tumor, two samples of Henrietta's cervix were removed—a healthy part and a cancerous part—without her permission.[7] The cells from her cervix were given to Dr. George Otto Gey. These cells would eventually become the HeLa immortal cell line, a commonly used cell line in biomedical research.[1]

In significant pain and without improvement, Lacks returned to Hopkins on August 8 for a treatment session, but asked to be admitted. She remained at the hospital until the day of her death.[1] She received treatment and blood transfusions, but died of uremic poisoning on October 4, 1951, at the age of 31.[8] A subsequent partial autopsy showed that the cancer had metastasized throughout her entire body.[1]

Lacks was buried without a tombstone in a family cemetery in Lackstown, a part of Clover in Halifax County, Virginia. Her exact burial location is not known, although the family believes it is within feet of her mother's gravesite.[1] Lackstown is the name of the land that has been held by the (black) Lacks family since they received it from the (white) Lacks family, who had owned the ancestors of the black Lackses when slavery was legal. Many members of the black Lacks family were also descended from the white Lacks family.[1] For decades, Henrietta Lacks' mother had the only tombstone of the five graves in the family cemetery in Lackstown, and Henrietta's own grave was unmarked.[8][9] In 2010, however, Dr. Roland Pattillo of the Morehouse School of Medicine donated a headstone for Lacks after reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.[10] The headstone, which is shaped like a book, reads:

Henrietta Lacks, August 01, 1920-October 04, 1951.

In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many.

Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever.

Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family[10][11]

Legacy

Scientific research

The cells from Henrietta's tumor were given to researcher George Gey, who "discovered that [Henrietta's] cells did something they'd never seen before: They could be kept alive and grow."[12] Before this, cells cultured from other cells would only survive for a few days. Scientists spent more time trying to keep the cells alive than performing actual research on the cells, but some cells from Lacks's tumor sample behaved differently from others. George Gey was able to isolate one specific cell, multiply it, and start a cell line. Gey named the sample HeLa, after the initial letters of Henrietta Lacks' name. As the first human cells grown in a lab that were "immortal" (they do not die after a few cell divisions), they could be used for conducting many experiments. This represented an enormous boon to medical and biological research.[1]

As reporter Michael Rogers stated, the growth of HeLa by a researcher at the hospital helped answer the demands of the 10,000 who marched for a cure to polio shortly before Lacks' death. By 1954, the HeLa strain of cells was being used by Jonas Salk to develop a vaccine for polio.[1][8] To test Salk's new vaccine, the cells were quickly put into mass production in the first-ever cell production factory.[13]

In 1955 HeLa cells were the first human cells successfully cloned.[14]

Demand for the HeLa cells quickly grew. Since they were put into mass production, Henrietta's cells have been mailed to scientists around the globe for "research into cancer, AIDS, the effects of radiation and toxic substances, gene mapping, and countless other scientific pursuits".[8] HeLa cells have been used to test human sensitivity to tape, glue, cosmetics, and many other products.[1] Scientists have grown some 20 tons of her cells,[1][15] and there are almost 11,000 patents involving HeLa cells.[1]

In the early 1970s, the family of Henrietta Lacks started getting calls from researchers who wanted blood samples from them to learn the family's genetics (eye colors, hair colors, and genetic connections). The family questioned this, which led to them learning about the removal of Henrietta's cells.[1]

Recognition

In 1996, Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, the state of Georgia and the mayor of Atlanta recognized the late Henrietta Lacks' family for her posthumous contributions to medicine and health research.[16]

Her life was commemorated annually by Turners Station residents for a few years after Morehouse's commemoration. A congressional resolution in her honor was presented by Robert Ehrlich following soon after the first commemoration of her, her family, and her contributions to science in Turner Station.

Events in the Turner Station's community have also commemorated the contributions of others including Mary Kubicek, the laboratory assistant who discovered that HeLa cells lived outside the body, as well as Dr. Gey and his nurse wife, Margaret Gey, who together after over 20 years of attempts were eventually able to grow human cells outside of the body.[1]

In 2011, Morgan State University granted her a posthumous honorary degree.[17]

On September 14, 2011, the Board of Directors of Washington ESD 114 Evergreen School District in Vancouver, Washington chose to name a new health and bioscience high school in her honor. The new school, which opened in the fall of 2013, is named Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School.[18] "It is such an honor to name our new school after a person who so impacted the world of medicine and science," said school board member Victoria Bradford, who also served on the naming committee. "It is also a privilege to be the first organization to publicly memorialize Henrietta Lacks by naming this school building after her."[19]

In media

In 1998 a one-hour BBC documentary[20][21] on Lacks and HeLa directed by Adam Curtis, won the Best Science and Nature Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival. Immediately following the film's airing in 1997, an article on HeLa cells, Lacks, and her family was published by reporter Jacques Kelly in The Baltimore Sun. In the 1990s, the Dundalk Eagle published the first article on her in a newspaper in Baltimore City and Baltimore County, and it continues to announce upcoming local commemorative activities. The Lacks family was also honored at the Smithsonian Institution.[22] In 2001, it was announced that the National Foundation for Cancer Research would be honoring "the late Henrietta Lacks for the contributions made to cancer research and modern medicine" on September 14. Because of the events of September 11, 2001, the event was canceled.[23]

In articles published in 2000 [24] and 2001[25] and in her 2010 book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot documents the histories of both the HeLa cell line and the Lacks family. Henrietta's husband, David Lacks, was told little following her death. Suspicions fueled by racial issues prevalent in the South (see Night Doctors) were compounded by issues of class and education. For their part, members of the Lacks family were kept in the dark about the existence of the tissue line. When its existence was revealed in two articles written in March 1976 by Michael Rogers, one in the Detroit Free Press[26] and one in Rolling Stone,[1][27] family members were confused about how Henrietta's cells could have been taken without consent and how they could still be alive 25 years after her death.[22]

In 2000 Mal Webb released a CD[28] with a song about Lacks called "Helen Lane".[29]

In May 2010 The Virginian-Pilot published two articles on Lacks, HeLa, and her family,[1][30] which mentions that the Morehouse School of Medicine has donated the money for Henrietta's grave as well as her daughter, Elsie, who died in 1955, to finally have headstones. Her grandchildren wrote her epitaph: "Henrietta Lacks August 01, 1920 – October 04, 1951 In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many. Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever. Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family"[1][30]

In May 2010 HBO announced that Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball would develop a film project based on Skloot's book.[30]

On May 17, 2010, NBC ran a fictionalized version of Lacks' story on Law & Order, titled "Immortal". An article in Slate called the episode "shockingly close to the true story."[31]

On May 31, 2011, Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine released the CD Enhanced Methods of Questioning with a song about Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa immortal cell line called "The Cells That Will Not Die".

In May 2012 self-proclaimed "Middle Eastern-psych-snap-gospel" band Yeasayer officially released "Henrietta", the first single from their third album Fragrant World. Lead singer Chris Keating reports that Henrietta Lacks' legacy inspired the creation of this song.[32]

Lacks and her story are discussed briefly in Brandon Cronenberg's Antiviral (2012).

In June 2013 Henrietta's oldest son, Lawrence Lacks, and his wife, Bobbette, authored and published a short, first-person digital memoir, "Hela Family Stories: Lawrence and Bobbette," available through www.helafamilystories.com. Lawrence shares his memories of his mother for the first time, and Bobbette discusses her struggle to save Henrietta's orphaned children from an abusive situation. "HeLa Family Stories" marks the first time members of the Lacks family have authored their own stories.[33]

In law and ethics

Neither Lacks nor her family gave her physician permission to harvest the cells. At that time, permission was neither required nor customarily sought.[34] The cells were later commercialized. In the 1980s, family medical records were published without family consent. This issue and Mrs. Lacks' situation was brought up in the Supreme Court of California case of Moore v. Regents of the University of California. On July 9, 1990, the court ruled that a person's discarded tissue and cells are not their property and can be commercialized.[35]

In March 2013, German researchers published the DNA code, or genome, of a strain of HeLa cells without permission from the Lacks family.[36] Later, in August 2013, an agreement by the family and the National Institutes of Health was announced that gave the family some control over access to the cells' DNA code and a promise of acknowledgement in scientific papers. In addition, two family members will join a six-member committee which will regulate access to the code.[36]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Batts, Denise Watson (2010-05-10). "Cancer cells killed Henrietta Lacks - then made her immortal". The Virginian-Pilot. pp. 1, 12–14. Retrieved 2012-08-19. Note: Some sources report her birthday as August 2, 1920, vs. August 1, 1920.

- ^ Grady, Denise (2010-02-01). "A Lasting Gift to Medicine That Wasn't Really a Gift". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Skloot 2010, p. 18 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSkloot2010 (help)

- ^ a b c Skoot, Rebecca (February 2010). "Excerpt From The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks". oprah.com. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ "Turner's Station African American Survey District, Dundalk, Baltimore County 1900–1950" (PDF). Baltimore County. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ a b "Baltimore county architectural survey African American Thematic Study" (PDF). Baltimore County Office of Planning and The Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Skloot 2010, p. 33 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSkloot2010 (help)

- ^ a b c d Smith, Van (2002-04-17). "Wonder Woman: The Life, Death, and Life After Death of Henrietta Lacks, Unwitting Heroine of Modern Medical Science". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Skloot, Rebecca (April 2000). "Henrietta's Dance". Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ a b Skloot, Rebecca (2010-05-29). "A Historic Day: Henrietta Lacks's Long Unmarked Grave Finally Gets a Headstone – Culture Dish". Scienceblogs.com. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ McLaughlin, Tom (2010-05-31). "An epitaph, at last | South Boston Virginia News". TheNewsRecord.com. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ Claiborne, Ron; Wright IV, Sydney (2010-01-31). "How One Woman's Cells Changed Medicine". ABC World News. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Skloot 2010, p. 96 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSkloot2010 (help)

- ^ ^ Puck TT, Marcus PI. A Rapid Method for Viable Cell Titration and Clone Production With Hela Cells In Tissue Culture: The Use of X-Irradiated Cells to Supply Conditioning Factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1955 Jul 15;41(7):432-7. URL: PNASJSTOR

- ^ Margonelli, Lisa (February 5, 2010). "Eternal Life". New York Times. New York. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Morehouse School of Medicine Hosts 14th Annual HeLa Women's Health Conference". MSM News. 2009-08-24. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ "Morgan Celebrates More than 1,200 Degree Recipients". Morgan State University. 2011-05-21. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Buck, Howard (2011-09-14). "Bioscience school gets official name". The Columbian. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ "New high school name to honor Henrietta Lacks". KATU. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ "The Way of All Flesh". Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ The Way of All Flesh by Adam Curtis[dead link] at Google Videos

- ^ a b Zielinski, Sarah (2010-01-22). "Henrietta Lacks' 'Immortal' Cells". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Skloot 2010, p. 299 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSkloot2010 (help)

- ^ Henrietta's Dance, Johns Hopkins Magazine, April 2000.

- ^ Cells That Save Lives are a Mother's Legacy, New York Times, November 17, 2001.

- ^ Rogers, Michael (March 21, 1976). "The HeLa Strain". Detroit Free Press.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Rogers, Michael (March 25, 1976). "The Double-Edged Helix". Rolling Stone.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "CDs (Mal Webb)". MalWebb.Com. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Webb, Mal. "Helen Lane". MalWebb.Com. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ a b c Batts, Denise Watson (2010-05-30). "After 60 years of anonymity, Henrietta Lacks has a headstone". The Virginian-Pilot. pp. HR1, 7. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ Thomas, June (2010-05-19). "Ripped From Which Headline? "Immortal"". Slate. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ "Yeasayer reveal new track 'Henrietta' – listen". NME. 2012-05-16.

- ^ http://www.dundalkeagle.com/component/content/article/26-front-page/46234-telling-the-story-in-their-own-words

- ^ Washington, Harriet "Henrietta Lacks: An Unsung Hero", Emerge Magazine, October 1994.

- ^ Skloot 2010 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSkloot2010 (help)[page needed]

- ^ a b Ritter, Malcolm (August 7, 2013). "Feds, family reach deal on use of DNA information". Seattle Times. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

Further reading

- Skloot, Rebecca (2010), The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, New York City: Random House, ISBN 978-1-4000-5217-2

- Russell Brown and James H M Henderson, 1983, "The Mass Production and Distribution of HeLa Cells at Tuskegee Institute", 1953–1955. J Hist Med allied Sci 38(4):415–43

- Harold M. Schmeck Jr. (1986-05-15). "Hela's Legacy". The New York Times.

- Michael Gold (January 1986). A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy and the Medical Scandal It Caused. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0887060991.

- Hannah Landecker 2000 "Immortality, In Vitro. A History of the HeLa Cell Line". In Brodwin, Paul E., ed.: Biotechnology and Culture. Bodies, Anxieties, Ethics. Bloomington/Indianapolis, 53–72, ISBN 0-253-21428-9

- Hannah Landecker, 1999, "Between Beneficence and Chattel: The Human Biological in Law and Science," Science in Context, 203–225.

- Hannah Landecker, 2007, Culturing Life: How Cells Became Technologies. "HeLa" is the title of the fourth chapter.

- Priscilla Wald, "American Studies and the Politics of Life" American Quarterly 64.2 (June 2012): 185-204

- Priscilla Wald, "Cells, Genes, and Stories: HeLa’s Journey from Labs to Literature," Genetics and the Unsettled Past: The Collision of Race, DNA and History, ed. Keith Wailoo, Alondra Nelson, and Catherine Lee, Rutgers University Press (2012): 247-65

- Priscilla Wald, "Science Fiction and Medical Ethics," The Lancet (June 14, 2009; 371.9629)

External links

- The Henrietta Lacks Foundation, a foundation established to, among other things, help provide scholarship funds and health insurance to Henrietta Lacks's family.

- RadioLab segment, "Henrietta's Tumor," featuring Deborah Lacks and audio of Skloot's interviews with her, and original recordings of scenes from the book.

- February 2010 CBS Sunday Morning Segment, "The Immortal Henrietta Lacks," featuring the Lacks Family

- Wired Magazine 2010 article with timeline of HeLa contributions to science

- The Way Of All Flesh — Documentary by Adam Curtis

- Tavis Smiley interview with Rebecca Skloot about The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

- New York Times review of Rebecca Skloot's book on Henrietta

- January 2010 Smithsonian magazine article

- Family Talks about Dead Mother Whose Cells fight Cancer (Jet Magazine – April 1, 1976)

- 25 Years after Death, Black Mother's Cells Live for Cancer Study (Jet Magazine – April 1, 1976)

- Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine

- Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School (HeLa High)