Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien Robespierre | |

|---|---|

Robespierre c. 1790, (anonymous), Musée Carnavalet, Paris | |

| President of the Committee of Public Safety | |

| In office 27 July 1793 – 27 July 1794 | |

| Preceded by | Georges Danton |

| Succeeded by | Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varenne |

| President of the National Convention | |

| In office 4 June 1794 – 17 June 1794 | |

| In office 22 August 1793 – 5 September 1793 | |

| Deputy of the National Convention | |

| In office 20 September 1792 – 27 July 1794 | |

| Deputy of the National Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 9 July 1789 – 30 September 1791 | |

| Deputy of the National Assembly | |

| In office 17 June 1789 – 9 July 1789 | |

| Member of the Estates General for the Third Estate | |

| In office 6 May 1789 – 16 June 1789 | |

| Constituency | Artois |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre 6 May 1758 Arras, Artois, France |

| Died | 28 July 1794 (aged 36) Place de la Révolution, Paris, France |

| Political party | Jacobin Club (1789–1794) |

| Other political affiliations | The Mountain (1792–1794) |

| Alma mater | Lycée Louis-le-Grand |

| Profession | Lawyer and politician |

| Signature | |

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (IPA: [mak.si.mi.ljɛ̃ fʁɑ̃.swa ma.ʁi i.zi.dɔʁ də ʁɔ.bɛs.pjɛʁ]; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and politician, and one of the best-known and most influential figures of the French Revolution.

As a member of the Estates-General, the Constituent Assembly and the Jacobin Club, he opposed the death penalty and advocated the abolition of slavery, while supporting equality of rights, universal male suffrage and the establishment of a republic. He opposed dechristianisation of France, war with Austria and the possibility of a coup by the Marquis de Lafayette. As a member of the Committee of Public Safety, he was an important figure during the period of the Revolution commonly known as the Reign of Terror, which ended a few months after his arrest and execution in July 1794 following the Thermidorian reaction. The Thermidorians accused him of being the "soul" of the Terror,[1] although his guilt in the brutal excesses of the Terror has not been proven.[2]

Influenced by 18th-century Enlightenment philosophes such as Rousseau and Montesquieu, he was a capable articulator of the beliefs of the left-wing bourgeoisie. His steadfast adherence and defense of the views he expressed earned him the nickname l'Incorruptible (The Incorruptible).[3] His reputation has gone through cycles. It peaked in the 1920s when the influential French historian Albert Mathiez rejected the common view of Robespierre as demagogic, dictatorial, and fanatical. Mathiez argued he was an eloquent spokesman for the poor and oppressed, an enemy of royalist intrigues, a vigilant adversary of dishonest and corrupt politicians, a guardian of the French Republic, an intrepid leader of the French Revolutionary government, and a prophet of a socially responsible state.[4] However, his reputation has suffered from his association with radical purification of politics by the killing of enemies.[5][6][7]

- XD hope this solves your little questions*

Early life

Maximilien Robespierre was born in Arras, in the old French province of Artois. His family has been traced back to the 12th century in Picardy; some of his direct ancestors in the male line were notaries in the village of Carvin near Arras from the beginning of the 17th century.[8] He is sometimes rumoured to have been of Irish descent, and it has been suggested that his surname could be a corruption of "Robert Speirs".[9] George Henry Lewes, Ernest Hamel, Jules Michelet, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Hilaire Belloc have all cited this theory although there appears to be little supporting evidence.

His paternal grandfather, also named Maximilien Robespierre, established himself in Arras as a lawyer. His father, Maximilien Barthélémy François de Robespierre, also a lawyer at the Conseil d'Artois, married Jacqueline Marguerite Carrault, the daughter of a brewer, in 1758. Maximilien was the oldest of four children and was conceived out of wedlock; his siblings were Charlotte, Henriette, and Augustin.[10] In 1764, Madame de Robespierre died a few days after childbirth. Her husband subsequently left Arras and traveled throughout Europe, only occasionally living in Arras, until his death in Munich in 1777; the children were brought up by their maternal grandfather and aunts.

Maximilien attended the collège (middle school) of Arras when he was eight, already literate.[11] In October 1769, on the recommendation of the bishop, he obtained a scholarship at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. Robespierre studied there until age 23, receiving his training as a lawyer. Upon his graduation, he received a 600-livre special prize for twelve years of exemplary academic success and personal good conduct.[12]

In school he learned to admire the idealised Roman Republic and the rhetoric of Cicero, Cato and other classic figures. His fellow pupils included Camille Desmoulins and Stanislas Fréron. He also read Swiss philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau during this time and adopted many of his principles. Robespierre grew intrigued by the idea of a "virtuous self", a man who stands alone accompanied only by his conscience.[13]

Shortly after his coronation, King Louis XVI visited Louis-le-Grand. Robespierre, then 17 and a prize-winning student, had been chosen out of five hundred pupils to deliver a speech to welcome the king. Perhaps due to rain, the royal couple remained in their coach throughout the ceremony and promptly left at its completion.[13]

Early politics

As an adult, and possibly even as a young man, the greatest influence on Robespierre's political ideas was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Robespierre's conception of revolutionary virtue and his program for constructing political sovereignty out of direct democracy came from Rousseau; and, in pursuit of these ideals, he eventually became known during the Jacobin Republic as "the Incorruptible".[14] Robespierre believed that the people of France were fundamentally good and were therefore capable of advancing the public well-being of the nation.[15]

Having completed his law studies, Robespierre was admitted to the Arras bar. The Bishop of Arras, Louis François Marc Hilaire de Conzié, appointed him criminal judge in the Diocese of Arras in March 1782. Although this appointment did not prevent him from practicing at the bar, he soon resigned owing to discomfort in ruling on capital cases arising from his early opposition to the death penalty.[13] He quickly became a successful advocate and chose, in principle, to represent the poor. During court hearings, he was known often to advocate the ideals of the Enlightenment and argue for the rights of man.[16] Later in his career, he read widely, and also became interested in society in general. He became regarded as one of the best writers and most popular young men of Arras.

In December 1783, he was elected a member of the academy of Arras, the meetings of which he attended regularly. In 1784, he obtained a medal from the academy of Metz for his essay on the question of whether the relatives of a condemned criminal should share his disgrace. He and Pierre Louis de Lacretelle, an advocate and journalist in Paris, divided the prize. Many of his subsequent essays were less successful, but Robespierre was compensated for these failures by his popularity in the literary and musical society at Arras, known as the "Rosatia". In its meetings he became acquainted with Lazare Carnot, who would later become his colleague on the Committee of Public Safety.

In 1788, he took part in a discussion of how the French provincial government should be elected, arguing in his Addresse à la nation artésienne that if the former mode of election by the members of the provincial estates were again adopted, the new Estates-General would not represent the people of France. It is possible he addressed this issue so that he could have a chance to take part in the proceedings and thus change the policies of the monarchy. King Louis XVI later announced new elections for all provinces, thus allowing Robespierre to run for the position of deputy for the Third Estate.[13]

Although the leading members of the corporation were elected, Robespierre, their chief opponent, succeeded in getting elected with them. In the assembly of the bailliage, rivalry ran still higher, but Robespierre had begun to make his mark in politics with the Avis aux habitants de la campagne (Arras, 1789). With this, he secured the support of the country electors; and, although only thirty, comparatively poor, and lacking patronage, he was elected fifth deputy of the Third Estate of Artois to the Estates-General. When Robespierre arrived at Versailles, he was relatively unknown, but he soon became part of the representative National Assembly which then transformed into the Constituent Assembly.[13]

While the Constituent Assembly occupied itself with drawing up a constitution, Robespierre turned from the assembly of provincial lawyers and wealthy bourgeois to the people of Paris. He was a frequent speaker in the Constituent Assembly, voicing many ideas for the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Constitutional Provisions, often with great success.[17][13] He was eventually recognized as second only to Pétion de Villeneuve – if second he was – as a leader of the small body of the extreme left; "the thirty voices" as Mirabeau contemptuously called them.

Jacobin Club

Robespierre soon became involved with the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution, known eventually as the Jacobin Club. This had consisted originally of the deputies from Brittany only. After the Assembly moved to Paris, the Club began to admit various leaders of the Parisian bourgeoisie to its membership. As time went on, many of the more intelligent artisans and small shopkeepers became members of the club.

Among such men, Robespierre found a sympathetic audience. As the wealthier bourgeois of Paris and right-wing deputies seceded from the club of 1789, the influence of the old leaders of the Jacobins, such as Barnave, Duport, Alexandre de Lameth, diminished. When they, alarmed at the progress of the Revolution, founded the club of the Feuillants in 1791, the left, including Robespierre and his friends, dominated the Jacobin Club.

On 15 May 1791, Robespierre proposed and carried the motion that no deputy who sat in the Constituent could sit in the succeeding Assembly.

The flight on 20 June, and subsequent arrest at Varennes of Louis XVI and his family resulted in Robespierre declaring himself at the Jacobin Club to be "ni monarchiste ni républicain" ("neither monarchist nor republican"). But this stance was not unusual; very few at this point were avowed republicans.

In 1790 he lived at rue de Saintonge, No. 9; at the time it was a remote area of the Tuileries. However, after the massacre on the Champ de Mars on 17 July 1791, fearing for his safety and in order to be nearer to the Assembly and the Jacobins, he moved to live in the house of Maurice Duplay, a cabinetmaker residing in the Rue Saint-Honoré and an ardent admirer of Robespierre. Robespierre lived there (with two short intervals excepted) until his death. In fact, according to his doctor, Souberbielle, Vilate, a juror on the Revolutionary Tribunal, and his host's youngest daughter (who would later marry Philippe Le Bas of the Committee of General Security), he became engaged to the eldest daughter of his host, Éléonore Duplay.[18] The sister of Maximilien claims that the wife of Maurice Duplay wished to marry her daughter to the Incorruptible, but this hope was never realized.

On 30 September, on the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, the people of Paris named Pétion and Robespierre as the two incorruptible patriots in an attempt to honor their purity of principles, their modest ways of living, and their refusal of bribes and offers.[16]

With the dissolution of the Assembly, he returned to Arras for a short visit, where he met with a triumphant reception. In November, he returned to Paris to take the position of public prosecutor of Paris.[19]

Opposition to war with Austria

In February 1792, Jacques Pierre Brissot, one of the leaders of the Girondist party in the Legislative Assembly, urged that France should declare war against Austria. Marat and Robespierre opposed him, because they feared the influence of militarism, which might be turned to the advantage of the reactionary forces. Robespierre was also convinced that the internal stability of the country was more important; this opposition from expected allies irritated the Girondists, and the war became a major point of contention between the factions. Robespierre countered, "A revolutionary war must be waged to free subjects and slaves from unjust tyranny, not for the traditional reasons of defending dynasties and expanding frontiers..." Indeed, argued Robespierre, such a war could only favor the forces of counter-revolution, since it would play into the hands of those who opposed the sovereignty of the people. The risks of Caesarism were clear, for in wartime the powers of the generals would grow at the expense of ordinary soldiers, and the power of the king and court at the expense of the Assembly. These dangers should not be overlooked, he reminded his listeners, "...in troubled periods of history, generals often became the arbiters of the fate of their countries."[20]

Robespierre warned against the threat of dictatorship, stemming from war, in the following terms:

If they are Caesars or Cromwells, they seize power for themselves. If they are spineless courtiers, uninterested in doing good yet dangerous when they seek to do harm, they go back to lay their power at their master's feet, and help him to resume arbitrary power on condition they become his chief servants.

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1791[21]

Robespierre also argued that force was not an effective or proper way of spreading the ideals of the Revolution:

The most extravagant idea that can arise in a politician's head is to believe that it is enough for a people to invade a foreign country to make it adopt their laws and their constitution. No one loves armed missionaries . . . The Declaration of the Rights of Man . . . is not a lightning bolt which strikes every throne at the same time . . . I am far from claiming that our Revolution will not eventually influence the fate of the world . . . But I say that it will not be today.

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[22]

In April 1792, Robespierre resigned the post of public prosecutor of Versailles, which he had officially held, but never practiced, since February, and started a journal, Le Défenseur de la Constitution. The journal served multiple purposes: countering the influence of the royal court in public policy, defending Robespierre from the accusations of Girondist leaders, and also giving voice to the economic interests of the broader masses in Paris and beyond.[23]

The National Convention

When the Legislative Assembly declared war against Austria on 20 April 1792, Robespierre responded by working to reduce the political influence of the officer class, the generals and the king. While arguing for the welfare of common soldiers, Robespierre urged new promotions to mitigate domination of the officer class by the aristocratic École Militaire; along with other Jacobins he also urged the creation of popular militias to defend France.[24] This sentiment reflected the perspective of more radical Jacobins including those of the Marseille Club, who in May and June 1792 wrote to Pétion and the people of Paris, "Here and at Toulon we have debated the possibility of forming a column of 100,000 men to sweep away our enemies... Paris may have need of help. Call on us!"[25]

Because French forces had suffered disastrous defeats and a series of defections at the onset of the war, Robespierre and Danton feared the possibility of a military coup d'état[26] above all led by the Marquis de Lafayette, who in June advocated the suppression of the Jacobin Club. Robespierre publicly attacked him in scathing terms: "General, while from the midst of your camp you declared war upon me, which you had thus far spared for the enemies of our state, while you denounced me as an enemy of liberty to the army, national guard and Nation in letters published by your purchased papers, I had thought myself only disputing with a general... but not yet the dictator of France, arbitrator of the state."[27]

In early June Robespierre proposed an end to the Monarchy and the subordination of the Assembly to the popular will.[28] Following the King's veto of the Legislative Assembly's efforts to raise a militia and suppress non-juring priests, the Monarchy faced an abortive insurrection on 20 June, exactly three years after the Tennis Court Oath.[29] Revolutionary militia (French: fédérés) entered Paris without the King's approval, and on 10 August 1792, insurrectionary National Guard of Paris, fédérés and sans-culottes led a successful assault upon the Tuileries Palace with the intention of overthrowing the Monarchy.[30]

On 16 August, Robespierre presented the petition of the Commune to the Legislative Assembly, demanding the establishment of a revolutionary tribunal and the summoning of a Convention chosen by universal suffrage.[31] Dismissed from his command of the French Northern Army, Lafayette fled France along with other sympathetic officers.

In September, Robespierre was elected first deputy for Paris to the National Convention. Robespierre and his allies took the benches high at the back of the hall, giving them the label 'the Montagnards', or 'the Mountain'; below them were the 'Manège' of the Girondists and then 'the Plain' of the independents. The Girondists at the Convention accused Robespierre of failing to stop the September Massacres. On 26 September, the Girondist Marc-David Lasource accused Robespierre of wanting to form a dictatorship. Rumours spread that Robespierre, Marat and Danton were plotting to establish a triumvirate. On 29 October, Louvet de Couvrai attacked Robespierre in a speech, possibly written by Madame Roland. On 5 November, Robespierre defended himself, the Jacobin Club and his supporters in and beyond Paris.

Upon the Jacobins I exercise, if we are to believe my accusers, a despotism of opinion, which can be regarded as nothing other than the forerunner of dictatorship. Firstly, I do not know what a dictatorship of opinion is, above all in a society of free men... unless this describes nothing more than the natural compulsion of principles. In fact, this compulsion hardly belongs to the man who enunciates them; it belongs to universal reason and to all men who wish to listen to its voice. It belongs to my colleagues of the Constituent Assembly, to the patriots of the Legislative Assembly, to all citizens who will invariably defend the cause of liberty. Experience has proven, despite Louis XVI and his allies, that the opinion of the Jacobins and of the popular clubs were those of the French Nation; no citizen has made them, and I did nothing other than share in them.

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[32]

Turning the accusations upon his accusers, Robespierre delivered one of the most famous lines of the French Revolution to the Assembly:

I will not remind you that the sole object of contention dividing us is that you have instinctively defended all acts of new ministers, and we, of principles; that you seemed to prefer power, and we equality... Why don't you prosecute the Commune, the Legislative Assembly, the Sections of Paris, the Assemblies of the Cantons and all who imitated us? For all these things have been illegal, as illegal as the Revolution, as the fall of the Monarchy and of the Bastille, as illegal as liberty itself... Citizens, do you want a revolution without a revolution? What is this spirit of persecution which has directed itself against those who freed us from chains?

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[33]

Robespierre's speech marked a profound political break between the Montagnards and the Girondins, strengthening the former in the context of an increasingly revolutionary situation punctuated by the fall of Louis XVI, the invasion of France and the September Massacres in Paris.[34] It also heralded increased involvement and intervention by the sans-culottes in revolutionary politics.[35]

Execution of Louis XVI

The Convention's unanimous declaration of a French Republic on 21 September 1792 left open the fate of the King; a commission was therefore established to examine evidence against him while the Convention's Legislation Committee considered legal aspects of any future trial. Most Montagnards favored judgement and execution, while the Girondins were divided concerning Louis' fate, with some arguing for royal inviolability, others for clemency, and some advocating lesser punishment or death.[36] On 20 November, opinion turned sharply against Louis following the discovery of a secret cache of 726 documents consisting of Louis' personal communications.[37]

Robespierre had taken ill in November and had done little other than support Saint-Just in his argument against the King's inviolability; Robespierre wrote in his Defenseur de la Constitution that a Constitution which Louis had violated himself, and which declared his inviolability, could not now be used in his defense.[38] Now, with the question of the King's fate occupying public discourse, Robespierre on 3 December delivered a speech that would define the rhetoric and course of Louis' trial.[39] Robespierre argued that the King, now dethroned, could function only as a threat to liberty and national peace, and that the members of the Assembly were not fair judges, but rather statesmen with responsibility for public safety:

Louis was a king, and our republic is established; the critical question concerning you must be decided by these words alone. Louis was dethroned by his crimes; Louis denounced the French people as rebels; he appealed to chains, to the armies of tyrants who are his brothers; the victory of the people established that Louis alone was a rebel; Louis cannot therefore be judged; he already is judged. He is condemned, or the republic cannot be absolved. To propose to have a trial of Louis XVI, in whatever manner one may, is to retrogress to royal despotism and constitutionality; it is a counter-revolutionary idea because it places the revolution itself in litigation. In effect, if Louis may still be given a trial, he may be absolved, and innocent. What am I to say? He is presumed to be so until he is judged. But if Louis is absolved, if he may be presumed innocent, what becomes of the revolution? If Louis is innocent, all the defenders of liberty become slanderers. Our enemies have been friends of the people and of truth and defenders of innocence oppressed; all the declarations of foreign courts are nothing more than the legitimate claims against an illegal faction. Even the detention that Louis has endured is, then, an unjust vexation; the fédérés, the people of Paris, all the patriots of the French Empire are guilty; and this great trial in the court of nature judging between crime and virtue, liberty and tyranny, is at last decided in favor of crime and tyranny. Citizens, take warning; you are being fooled by false notions; you confuse positive, civil rights with the principles of the rights of mankind; you confuse the relationships of citizens amongst themselves with the connections between nations and an enemy that conspires against it; you confuse the situation of a people in revolution with that of a people whose government is affirmed; you confuse a nation that punishes a public functionary to conserve its form of government, and one that destroys the government itself. We are falling back upon ideas familiar to us, in an extraordinary case that depends upon principles we have never yet applied.

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[40]

In arguing for a judgment by the elected Convention without trial, Robespierre supported the recommendations of Jean-Baptiste Mailhe, who headed the commission reporting on legal aspects of Louis' trial or judgment. Unlike some Girondins, Robespierre would specifically oppose judgment by primary assemblies or a referendum, believing that this could cause civil war.[41] While he called for a trial of queen Marie Antoinette and the imprisonment of the Dauphin, Robespierre argued for the death penalty in the case of the king:

As for myself, I abhor the death penalty administered by your laws, and for Louis I have neither love, nor hate; I hate only his crimes. I have demanded the abolition of the death penalty at your Constituent Assembly, and am not to blame if the first principles of reason appeared to you moral and political heresies. But if you will never reclaim these principles in favor of so much evil, the crimes of which belong less to you and more to the government, by what fatal error would you remember yourselves and plead for the greatest of criminals? You ask an exception to the death penalty for him alone who could legitimize it? Yes, the death penalty is in general a crime, unjustifiable by the indestructible principles of nature, except in cases protecting the safety of individuals or the society altogether. Ordinary misdemeanors have never threatened public safety because society may always protect itself by other means, making those culpable powerless to harm it. But for a king dethroned in the bosom of a revolution, which is as yet cemented only by laws; a king whose name attracts the scourge of war upon a troubled nation; neither prison, nor exile can render his existence inconsequential to public happiness; this cruel exception to the ordinary laws avowed by justice can be imputed only to the nature of his crimes. With regret I pronounce this fatal truth: Louis must die so that the nation may live.

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1792[42]

On 15 January 1793, Louis XVI was voted guilty of conspiracy and attacks upon public safety by 691 of 749 deputies; none voted for his innocence. Four days later, 387 deputies voted for death as penalty, 334 voted for detention or a conditional death penalty, and 28 abstained or were absent. Louis was executed two days later in the Place de la Révolution.

Destruction of the Girondists

After the King's execution, the influence of Robespierre, Danton and the pragmatic politicians increased at the expense of the Girondists. The Girondists refused to have anything more to do with Danton and because of this the government became more divided. In May 1793, Desmoulins, at the behest of Robespierre and Danton, published his Histoire des Brissotins, an elaboration on the earlier article Jean-Pierre Brissot, démasqué, a scathing attack on Brissot and the Girondists.

The economic situation was rapidly deteriorating and Paris populace became restless. Sectional activists demanded "maximum" on basic foodstuff. Rioting persisted and a commission of inquiry of twelve members was set up, on which only Girondins sat. Popular militants were arrested. On 25 May the Commune demanded that arrested patriots to be released and sections drew the list of 22 prominent Girondists to be removed from the Convention. Maximin Isnard declared that Paris will be destroyed if it came out against the provincial deputies. Robespierre preached a moral "insurrection against the corrupt deputies" at the Jacobin Club. The Jacobins declared themselves in state of insurrection. On the 29 May the delegates representing thirty-three of the Paris sections formed an insurrectionary committee.[43]

On 2 June 80,000 armed sans-culottes surrounded the Convention. After an attempt of deputies to exit collided with guns, the deputies resigned themselves to declare the arrest of 29 leading Girondins. During the insurrection Robespierre had scrawled a note in his memorandum-book:

What we need is a single will (il faut une volonté, une). It must be either republican or royalist. If it is to be republican, we must have republican ministers, republican papers, republican deputies, a republican government. The internal dangers come from the middle classes; in order to defeat the middle classes we must rally the people... The people must ally itself with the Convention, and the Convention must make use of the people.

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1793 [44]

Reign of Terror

"To punish the oppressors of humanity is clemency; to forgive them is barbarity."

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1794[45]

After the fall of the monarchy, France faced troubles as the war and the civil war continued. A stable government was needed to quell the chaos.[16] On 11 March 1793, a Revolutionary Tribunal was established by Jacobins in the Convention.[46] On 6 April, the nine-member Committee of Public Safety replaced the larger Committee of General Defense. On 27 July 1793, Robespierre was elected to the Committee, although he had not sought the position.[47]

The Committee of General Security began to manage the country's internal police. Terror was formally instituted as a legal policy by the Convention on 5 September 1793, in a proclamation which read, "It is time that equality bore its scythe above all heads. It is time to horrify all the conspirators. So legislators, place Terror on the order of the day! Let us be in revolution, because everywhere counter-revolution is being woven by our enemies. The blade of the law should hover over all the guilty."[47]

Though nominally all members of the committee were equal, Robespierre was presented during the Thermidorian Reaction by the surviving protagonists of the Terror, especially Bertrand Barère, as prominent. They may have exaggerated his role to downplay their own contribution and used him as a scapegoat after his death.[48]

As an orator, he praised revolutionary government and argued that "terror" – at least as he defined it – was necessary, laudable and inevitable. It was Robespierre's belief that the Republic and virtue were of necessity inseparable. He reasoned that the Republic could be saved only by the virtue of its citizens, and that a Robespierrist Terror was virtuous because it attempted to maintain the Revolution and the Republic. For example, in his Report on the Principles of Political Morality, given on 5 February 1794, Robespierre stated:

If virtue be the spring of a popular government in times of peace, the spring of that government during a revolution is virtue combined with terror: virtue, without which terror is destructive; terror, without which virtue is impotent. Terror is only justice prompt, severe and inflexible; it is then an emanation of virtue; it is less a distinct principle than a natural consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing wants of the country ... The government in a revolution is the despotism of liberty against tyranny.[49]

Robespierre’s speeches were exceptional, and he had the power to change the views of almost any audience. His speaking techniques included invocation of virtue and morals, and quite often the use of rhetorical questions in order to identify with the audience. He would gesticulate and use ideas and personal experiences in life to keep listeners' attentions. His final method was to state that he was always prepared to die in order to save the Revolution.[50]

Doyle says, "It is not violent fulminations that characterise Robespierre's speeches on the Terror. It is the language of unmasking, unveiling, revealing, discovering, exposing the enemy within, the enemy hidden behind patriotic posturings, the language of suspicion."[51] Because he believed that the Revolution was still in progress, and in danger of being sabotaged, he made every attempt to instill in the populace and Convention the urgency of carrying out the Terror.

Robespierre saw no room for mercy in his Terror, stating that "slowness of judgments is equal to impunity" and "uncertainty of punishment encourages all the guilty". Throughout his Report on the Principles of Political Morality, Robespierre assailed any stalling of action in defense of the Republic. In his thinking, there was not enough that could be done fast enough in defence against enemies at home and abroad. A staunch believer in the teachings of Rousseau, Robespierre believed that it was his duty as a public servant to push the Revolution forward, and that the only rational way to do that was to defend it on all fronts. The Report did not merely call for blood but also expounded many of the original ideas of the 1789 Revolution, such as political equality, suffrage and abolition of privileges.[52]

In the winter of 1793–94, a majority of the Committee decided that the Hébertist party would have to perish or its opposition within the Committee would overshadow the other factions due to its influence in the Commune of Paris. Robespierre also had personal reasons for disliking the Hébertists for their "atheism" and "bloodthirstiness", which he associated with the old aristocracy.[19]

"On the 4th of February 1794 under the leadership of Maxmilien Robespierre, the French Convention voted for the abolition of slavery. The Jacobins had established the idea of liberty, but it was a conception which favoured the emergent bourgeoisie, and it was this idea of liberty signifying the freedom to trade which took precedence over the ideas of equality and fraternity. It was this corruption of the French revolution by a rapacious cabal of the French bourgeoisie that Robespierre fought so fanatically against. In fact, during the Reign of Terror, Robespierre had huge support among the poor of Paris and he is still revered by the poor of Haiti today."

– Centre for Research on Globalization[53]

In early 1794, he finally broke with Danton, who had angered many other members of the Committee of Public Safety with his more moderate views on the Terror, but whom Robespierre had, until this point, persisted in defending. Subsequently, he joined in attacks on the Dantonists and the Hébertists.[13] Robespierre charged his opponents with complicity with foreign powers.

From 13 February to 13 March 1794, Robespierre withdrew from active business on the Committee due to illness. On 15 March, he reappeared in the Convention. Hébert and nineteen of his followers were arrested on 19 March and guillotined on 24 March. Danton, Desmoulins and their friends were arrested on 30 March and guillotined on 5 April.

Georges Couthon, his ally on the Committee, introduced and carried on 10 June the drastic Law of 22 Prairial. Under this law, the Tribunal became a simple court of condemnation without need of witnesses. Historians frequently debate the reasons behind Robespierre's support of the Law of 22 Prairial: some consider it an attempt to extend his influence into a dictatorship, while others argue it was adopted to expedite the passage of the reformist, land-redistributive Ventôse Decrees.[citation needed]

Cult of the Supreme Being

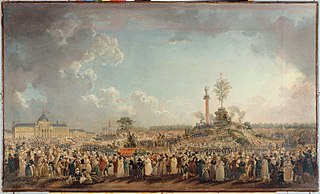

Robespierre's desire for revolutionary change was not limited to the political realm. He opposed the power of the Catholic Church and the Pope, and especially was opposed to its celibacy policies.[54] Having denounced the excesses of dechristianization, he sought to instill a spiritual resurgence in the French nation based on Deist beliefs. Accordingly, on 7 May 1794, Robespierre supported a decree passed by the Convention that established an official religion, known historically as the Cult of the Supreme Being. The notion of the Supreme Being was based on ideas that Jean-Jacques Rousseau had outlined in The Social Contract. A nationwide "Festival of the Supreme Being" was held on 8 June (which was also the Christian holiday of Pentecost). The festivities in Paris were held in the Champ de Mars, which was renamed the Champ de la Réunion ("Field of Reunion") for that day. This was most likely in honor of the Champ de Mars Massacre where the Republicans first rallied against the power of the Crown.[55] Robespierre, who happened to be President of the Convention that week, walked first in the festival procession and delivered a speech in which he emphasised his concept of a Supreme Being:

Is it not He whose immortal hand, engraving on the heart of man the code of justice and equality, has written there the death sentence of tyrants? Is it not He who, from the beginning of time, decreed for all the ages and for all peoples liberty, good faith, and justice? He did not create kings to devour the human race. He did not create priests to harness us, like vile animals, to the chariots of kings and to give to the world examples of baseness, pride, perfidy, avarice, debauchery and falsehood. He created the universe to proclaim His power. He created men to help each other, to love each other mutually, and to attain to happiness by the way of virtue.[56]

by Pierre-Antoine Demachy (1794).

Throughout the "Festival of the Supreme Being", Robespierre was beaming with joy; not even the negativity of his colleagues could disrupt his delight. He was able to speak of the things about which he was truly passionate, including Virtue and Nature, typical deist beliefs, and, of course, his disagreements with atheism. Everything was arranged to the exact specifications that had been previously set before the ceremony; the ominous and symbolic guillotine had been moved to the original standing place of the Bastille, all of the people were placed in the appropriate area designated to them, and everyone was dressed accordingly.[57] Not only was everything going smoothly, but the Festival was also Robespierre’s first appearance in the public eye as an actual leader for the people, and also as President of the Convention, to which he had been elected only four days earlier.[57]

While for some it was an excitement to see him at his finest, many other leaders involved in the Festival agreed that Robespierre had taken things a bit too far. Multiple sources state that Robespierre came down the mountain in a way that resembled Moses as the leader of the people,[58] and one of his colleagues, Jacques-Alexis Thuriot, was heard saying, "Look at the bugger; it’s not enough for him to be master, he has to be God".[58]

Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier used a report to the Convention on Catherine Théot as an opportunity to attack Robespierre and his beliefs.[59] Théot who was a seventy-eight-year old, self-declared "prophetess" who had, at one point, been imprisoned in the Bastille.[59] By stating that Robespierre was the "herald of the Last Days, prophet of the New Dawn",[60] (because his festival had fallen on the Pentecost, traditionally a day revealing "divine manifestation"), Catherine Théot made it seem that Robespierre had made these claims himself, to her. Many of her followers were also supporters or friends of Robespierre, which made it seem as if he were attempting to create a new religion, with himself as its god. Although Robespierre had nothing to do with Catherine Théot or her followers, many assumed that he was on a path to dictatorship, and it sent a current of fear throughout the Convention, contributing to his downfall the following July.

Downfall

On 23 May 1794, only one day after the attempted assassination of Collot d'Herbois, Robespierre's life was also in danger: a young woman by the name of Cécile Renault was arrested after having approached his place of residence with two small knives; she was executed one month later. At this point, the decree of 22 Prairial (also known as law of 22 Prairial) was introduced to the public without the consultation from the Committee of General Security, which, in turn, doubled the number of executions permitted by the Committee of Public Safety.[61]

This law permitted executions to be carried out even under simple suspicion of citizens thought to be counter-revolutionaries without extensive trials. When the Committee of Public Safety allowed this law to be passed, the Convention began to question them, out of fear that Robespierre and his allies might come after certain members of the Convention and even the Committee itself due to the excesses carried out by its on-mission representatives such as Joseph Fouché, Jean-Baptiste Carrier, Jean-Lambert Tallien, and several others.[62] This was part of the beginning of Robespierre's downfall.[63]

Reports were coming into Paris about excesses committed by the envoys sent en-mission to the provinces, particularly Jean-Lambert Tallien in Bordeaux and Joseph Fouché in Lyons. Robespierre tirelessly worked almost alone — having been opposed by other leading political figures and accused of being a counterrevolutionary for his relative moderation — to curb their excesses, having them recalled to Paris to account for their actions and then expelling them from the Jacobin Club. They, however, evaded arrest. Fouché spent the evenings moving house to house, warning members of the Convention that Robespierre was after them, whilst organising a coup d'état.[64]

Robespierre appeared at the Convention on 26 July (8th Thermidor, year II, according to the Revolutionary calendar), and delivered a two-hour-long speech. He defended himself against charges of dictatorship and tyranny, and then proceeded to warn of a conspiracy against the Republic. Specifically, he railed against the bloody excesses he had observed during the Terror. He also implied that members of the Convention were a part of this conspiracy, though when pressed he refused to provide any names. The speech, however, alarmed members, particularly given Fouché's warnings. These members who felt that Robespierre was alluding to them tried to prevent the speech from being printed, and a bitter debate ensued until Barère forced an end to it. Later that evening, Robespierre delivered the same speech again at the Jacobin Club, where it was very well received.[65]

The following day, Saint-Just began to give a speech in support of Robespierre. However, those who had seen him working on his speech the night before expected accusations to arise from it. Saint-Just had time to give only a small part of his speech before Jean-Lambert Tallien interrupted him. While the accusations began to pile up, Saint-Just remained uncharacteristically silent. Robespierre then attempted to secure the tribune to speak, but his voice was shouted down. Robespierre soon found himself at a loss for words after one deputy called for his arrest; another deputy, Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier, gave a mocking impression of him. When one deputy realised Robespierre's inability to respond, the man shouted, "The blood of Danton chokes him!"[66] Robespierre then finally regained his voice to reply with his one recorded statement of the morning, demanding to know why, when he had been the only one left protecting Danton in the end, he was now being blamed for the other man's death: "Is it Danton you regret? ... Cowards! Why didn't you defend him?"[67]

Arrest

The Convention ordered the arrest of Robespierre, his brother Augustin, Couthon, Saint-Just, François Hanriot, and Le Bas. Troops from the Commune, under General Coffinhal, arrived to free the prisoners and then marched against the Convention itself. The Convention responded by ordering troops of its own under Barras to be called out. When the Commune's troops heard the news of this, order began to break down, and Hanriot ordered his remaining troops to withdraw to the Hôtel de Ville, where Robespierre and his supporters also gathered. The Convention declared them to be outlaws, meaning that upon verification the fugitives could be executed within twenty-four hours without a trial. As the night went on, the forces of the Commune deserted the Hôtel de Ville and, at around two in the morning, those of the Convention under the command of Barras arrived there. In order to avoid capture, Augustin Robespierre threw himself out of a window, only to break both of his legs; Couthon was found lying at the bottom of a staircase; Le Bas committed suicide; and another radical shot himself in the head.

Robespierre tried to kill himself with a pistol but managed only to shatter his lower jaw,[68] although some eyewitnesses[69] claimed that Robespierre was shot by Charles-André Merda.

Execution

For the remainder of the night, Robespierre was moved to a table in the room of the Committee of Public Safety where he awaited execution. He lay on the table bleeding abundantly until a doctor was brought in to attempt to stop the bleeding from his jaw. Robespierre's last recorded words may have been "Merci, monsieur," to a man who had given him a handkerchief for the blood on his face and clothing.[70] Later, Robespierre was held in the same containment chamber where Marie Antoinette, the wife of King Louis XVI, had been held.

The next day, 28 July 1794, Robespierre was guillotined without trial in the Place de la Révolution. His brother Augustin, Couthon, Saint-Just, Hanriot, and twelve other followers, among them the cobbler Antoine Simon, the jailor of Louis-Charles, Dauphin of France, were also executed. When clearing Robespierre's neck, the executioner tore off the bandage that was holding his shattered jaw in place, causing Robespierre to produce an agonized scream until the fall of the blade silenced him.[71] Together with those executed with him, he was buried in a common grave at the newly opened Errancis Cemetery (cimetière des Errancis) (March 1794 – April 1797)[72] (near what is now the Place Prosper-Goubaux). A plaque indicating the former site of the cimetière des Errancis is located at 97 rue de Monceau, Paris 75008. Between 1844 and 1859 (probably in 1848), the remains of all those buried there were moved to the Catacombs of Paris.

Legacy and memory

The 'Incorruptible', correct to the last, had left no debts. His property was sold by auction in the Palais Royale, early in 1796, and fetched 38,601 livres — something over £100.[73]

Maximilien Robespierre remains a controversial figure to this day. Apart from one Metro station in Montreuil (a Paris suburb) and several streets named after him in about twenty towns, there are no memorials nor monuments to him in France. By making himself the embodiment of virtue and of total commitment, he took control of the Revolution in its most radical and bloody phase – the Jacobin republic. His goal in the Terror was to use the guillotine to create what he called a 'republic of virtue', wherein terror and virtue, his principles, would be imposed. He argued, "Terror is nothing more than speedy, severe and inflexible justice; it is thus an emanation of virtue; it is less a principle in itself, than a consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing needs of the patrie."[74]

Terror was thus a tool to accomplish his overarching goals for democracy. Historian Ruth Scurr wrote that as for Robespierre's vision for France he wanted a "democracy for the people, who are intrinsically good and pure of heart; a democracy in which poverty is honorable, power innocuous, and the vulnerable safe from oppression; a democracy that worships nature—not nature as it really is, cruel and disgusting, but nature sanitized, majestic, and, above all, good."[75]

In terms of historiography, he has several defenders. Marxist historian Albert Soboul viewed most of the measures of the Committee for Public Safety as necessary for the defense of the Revolution and mainly regretted the destruction of the Hébertists and other enragés.

Robespierre's main ideal was to ensure the virtue and sovereignty of the people. He disapproved of any acts which could be seen as exposing the nation to counter-revolutionaries and traitors, and became increasingly fearful of the defeat of the Revolution. He instigated the Terror and the deaths of his peers as a measure of ensuring a Republic of Virtue; but his ideals went beyond the needs and wants of the people of France. He became a threat to what he had wanted to ensure and the result was his downfall.[13]

He was a bourgeois: Albert Soboul, according to Ishay, argues that he and Saint-Just "were too preoccupied in defeating the interest of the bourgeoisie to give their total support to the sans-culottes, and yet too attentive to the needs of the sans-culottes to get support from the middle class."[76] For Marxists like Soboul, Robespierre's petit-bourgeois class interests were fatal to his mission.[77]

Jonathan Israel is sharply critical of Robespierre for repudiating the true values of the radical Enlightenment. He argues, "Jacobin ideology and culture under Robespierre was an obsessive Rousseauste moral Puritanism steeped in authoritarianism, anti-intellectualism, and xenophobia," and it repudiated free expression, basic human rights, and democracy."[78]

Robespierre has continued to fascinate biographers. Notable recent books in English include Colin Haydon and William Doyle's Robespierre (1999), John Hardman's Robespierre (1999), Ruth Scurr's Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution, Otto J. Scott's Robespierre: The Voice of Virtue (2011), and most recently Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life by Peter McPhee (2012).

After the October Revolution, Robespierre found ample praise in the Soviet Union, resulting for example in the construction of two statues of him – one in Saint Petersburg, and another in Moscow.

References

- ^ Pierre Serna, La République des girouettes: 1789–1815... et au-delà : une anomalie politique, la France de l'extrême centre, Éditions Champ Vallon, 2005, 570 p. (ISBN 9782876734135), p. 369.

- ^ Albert Mathiez, « Robespierre terroriste », dans Études sur Robespierre, 1988, p. 63 et 70, et Jean-Clément Martin, Violence et Révolution. Essai sur la naissance d'un mythe national, 2006, p. 224.

- ^ Thompson, J. M. "Robespierre," vol. I, p. 174, Basil Blackwell, Oxford: 1935.

- ^ Albert Mathiez, "Robespierre: l'histoire et la légende," Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française (1977) 49#1 pp 3–31.

- ^ Joseph I. Shulim "Robespierre and the French Revolution," American Historical Review (1977) 82#1 pp. 20–38 in JSTOR

- ^ Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (2006)

- ^ There are two ways of totally misunderstanding Robespierre as historical figure: one is to detest the man, the other is to make too much of him. It is absurd, of course, to see the lawyer from Arras as a monstrous usurper, the recluse as a demagogue, the moderate as bloodthirsty tyrant, the democrat as a dictator. On the other hand, what is explained about his destiny once it is proved that he really was the Incorruptible? The misconception common to both schools arises from the fact that they attribute to the psychological traits of the man the historical role into which he was thrust by events and the language he borrowed from them. Robespierre is an immortal figure not because he reigned supreme over the Revolution for a few months, but because he was the mouthpiece of its purest and most tragic discourse.

Furet, François (1989). Interpreting the French Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0521280494. Retrieved 26 January 2014. - ^ "Généalogie de Robespierre".

- ^ Carr, J. L. (1972.) Robespierre: the force of circumstance, Constable, p. 10.

- ^ "In Memory Of Maximillien (The Incorruptible) De Robespierre". Christian Memorials. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ Robespierre: the force of circumstance. 1972.

- ^ Scurr, Ruth. Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. New York: Henry Holt, 2006. pp. 22, 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Scurr, Ruth (2006). Fatal Purity.

- ^ William Doyle and Colin Haydon, Robespierre (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 56.

- ^ Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004), 73.

- ^ a b c Robespierre: Portrait of a Revolutionary Democrat. 1975.

- ^ The first to have made motto "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" was Maximilien Robespierre in his speech "On the organization of the National Guard" (French: Discours sur l'organisation des gardes nationales) on 5 December 1790, article XVI, and disseminated widely throughout France by the popular Societies.

Discours sur l'organisation des gardes nationales

Article XVI.

On their souls engraved these words: FRENCH PEOPLE, & below: FREEDOM, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY. The same words are inscribed on flags which bear the three colors of the nation.

(French: XVI. Elles porteront sur leur poitrine ces mots gravés : LE PEUPLE FRANÇAIS, & au-dessous : LIBERTÉ, ÉGALITÉ, FRATERNITÉ. Les mêmes mots seront inscrits sur leurs dra-peaux, qui porteront les trois couleurs de la na-tion.)

Gauthier, Florence (1992). Triomphe et mort du droit naturel en Révolution, 1789-1795-1802. Paris: éd. PUF/ pratiques théoriques. p. 129. - ^ Charlotte Robespierre, Mémoires, chapter III

- ^ a b Robespierre: Or the tyranny of the Majority. 1971.

- ^ By Forrest, A. "Robespierre, the war and its organization." In Haydon, D., and Doyle, W., Eds. "Robespierre," p.130. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1999.

- ^ From Robespierre's speech to the National Assembly on 18 December 1791. Cited in Forrest, A. "Robespierre, the war and its organization." In Haydon, D., and Doyle, W., Eds. "Robespierre," p.130. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1999.

- ^ Bell, David (2007). The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It. p. 118: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Mazauric, C., "Defenseur de la Constitution," in Soboul, A., Ed., "Dictionnaire historique de la Revolution francaise," PUF 2005: Paris.

- ^ Forrest, A. "Robespierre, the War and its Organization," in Haydon, C. and Doyle, W., Eds., "Robespierre," pp.133–135, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1999.

- ^ Quoted in Kennedy, M. L., "The Jacobin Clubs in the French Revolution: the Middle Years," pp.254–255, Princeton University Press, Princeton: 1999.

- ^ Thompson, J. M. "Robespierre," vol. I, p.233, Basil Blackwell, Oxford: 1935.

- ^ Laurent, Gustave (1939). Oeuvres Completes de Robespierre (in French). Vol. IV. Nancy: Imprimerie de G. Thomas. pp. 165–166. OCLC 459859442.

- ^ Hampson, N. "Robespierre and the Terror," in Haydon, C. and Doyle, W., Eds., "Robespierre," pp.162, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1999.

- ^ Pfeiffer, L. B., "The Uprising of June 20, 1792," p.221. New Era Printing Company, Lincoln: 1913.

- ^ Monnier, R., "Dix Aout," in Soboul, A., Ed., "Dictonnaire de la Revolution francaise," p.363, PUF, Paris: 2005.

- ^ Hampson, Norman. The Life and Opinions of Maximilien Robespierre. London: Duckworth, 1974. 120.

- ^ Bouloiseau, M., Dautry, J., Lefebvre, G. and Soboul, A., Eds., "Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre," pp.83–84, Tome IX, Discours. Presses Universitaires de France.

- ^ Bouloiseau et al. "Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre," pp.88–89, Tome IX, Discours.

- ^ Bertaud, J-P. "Robespierre," in Soboul, A., Ed., Dictionnaire historique de la Revolution francaise, pp.918–919, PUF, 2005: Paris.

- ^ Vovelle, M., "La Revolution Francaise," pp.28–29, Armand Colin, Paris: 2006.

- ^ Kennedy, M. L., "The Jacobin Clubs in the French Revolution: The Middle Years," pp.308–310, Princeton University Press, Princeton: 1988.

- ^ Gendron, F., "Armoir de Fer," in Soboul, A., Ed., "Dictionnaire historique de la Revolution francaise," p.42, PUF, Paris: 2005.

- ^ Bouloiseau et al. "Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre," pp.104–105, 120, Tome IX, Discours.

- ^ Thompson, J. M. "Robespierre," vol. I, p.292-300, Basil Blackwell, Oxford: 1935.

- ^ Bouloiseau, et al. "Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre," pp.121–122, Tome IX, Discours.

- ^ Dorigny, M., "Procès du Roi," in Soboul, A., Ed., "Dictionnaire historique de la Revolution francaise," p.867, PUF, Paris: 2005.

- ^ Bouloiseau, et al. "Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre," pp.129–130, Tome IX, Discours.

- ^ Albert Soboul, The French Revolution: 1787–1799 (1974) p 309

- ^ Albert Mathiez, The French Revolution (1927) p 333

- ^ Susan Dunn (2000). Sister Revolutions: French Lightning, American Light. Macmillan. p. 118.

- ^ Furet, François; Ozouf, Mona (1989). A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 216, 341. ISBN 978-0-674-17728-4. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ a b Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005. 178–179.

- ^ Serna, Pierre (2005). La République des girouettes : (1789 – 1815 ... et au-delà) : une anomalie politique: la France de l'extrême centre (in French). Seyssel: Champ Vallon. ISBN 978-2-87673-413-5.

- ^ "On the Principles of Political Morality, February 1794". Modern History Sourcebook. 1997.

- ^ Schama 1989, p. 579.

- ^ Robespierre. 1999. page 27

- ^ Gordon Kerr. Leaders Who Changed the World. Canary Press. p. 174.

- ^ France and the History of Haiti by Gearóid Ó Colmáin, Global Research, January 22, 2010

- ^ Otto J. Scott (1974). Robespierre. Transaction Publishers. p. 107.

- ^ Andress, David. The Terror, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007. 307

- ^ Robespierre, M. "The Cult of the Supreme Being", in Modern History Sourcebook, 1997

- ^ a b Andress, David. "The Terror", Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007. 308

- ^ a b Andress, David. The Terror, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007. 310

- ^ a b Andress, David. The Terror, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007. 323

- ^ Andress, David, The Terror, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007, p. 323

- ^ Schama 1989, p. 836.

- ^ Jean Jaures, "The Law of Prairial and the Great Terror (Fall, year IV)", in Socialist History of the French Revolution (translated by Mitchell Abidor), Marxists.org

- ^ Carr, John Lawrence, "Robespierre: the Force of Circumstance", St. Martin's Press, New York, 1972. 154

- ^ Paris in the Terror, Stanley Loomis

- ^ Schama 1989, p. 841-842

- ^ Schama 1989, p. 842–844.

- ^ Korngold, Ralph 1941, p. 365, Robespierre and the Fourth Estate Retrieved 27 July 2014

- ^ John Laurence Carr, Robespierre; the force of circumstance, Constable, 1972, p. 54.

- ^ Jan Ten Brink (translated by J. Hedeman), Robespierre and the red terror, Hutchinson & Co., 1899, p. 399.

- ^ Andress, David. "The Terror", Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2007. 343

- ^ Schama 1989, p. 845-846.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Landrucimetieres.fr

- ^ Thompson 1988.

- ^ Marisa Linton, "Robespierre and the Terror," History Today, Aug 2006, Vol. 56 Issue 8, pp 23–29

- ^ Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (2006) p. 358

- ^ Micheline Ishay (1995). Internationalism and Its Betrayal. U. of Minnesota Press. p. 65.

- ^ Peter McPhee (2012). Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life. Yale University Press. p. 268.

- ^ Jonathan Israel, Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre (2014) p 521

Further reading

- Bienvenu, Richard, ed. The Ninth of Thermidor: the fall of Robespierre (Oxford University Press, 1968)

- Brinton, Crane. The Jacobins: An Essay in the New History. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2011.

- Carr, John. (1972). Robespierre: the force of circumstance. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Cobban, Alfred. "The Fundamental Ideas of Robespierre," English Historical Review Vol. 63, No. 246 (January 1948), pp. 29–51 JSTOR

- Cobban, Alfred. "The Political Ideas of Maximilien Robespierre during the Period of the Convention," English Historical Review Vol. 61, No. 239 (January 1946), pp. 45–80 in JSTOR

- Doyle, William, Haydon, Colin (eds.) (1999). Robespierre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59116-3.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) A collection of essays covering not only Robespierre's thoughts and deeds but also the way he has been portrayed by historians and fictional writers alike.- Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine by Hilary Mantel in the London Review of Books, Vol. 22, No. 7, 30 March 2000.

- Eagan, James Michael (1978). Maximilien Robespierre: Nationalist Dictator. New York: Octagon Books. ISBN 0-374-92440-6. Presents Robespierre as the origin of Fascist dictators.

- Goldstein Sepinwall, Alyssa. "Robespierre, Old Regime Feminist? Gender, the Late Eighteenth Century, and the French Revolution Revisited," Journal of Modern History Vol. 82, No. 1 (March 2010), pp. 1–29 in JSTOR argues he was an early feminist, but by 1793 he joined the other Jacobins who excluded women from political and intellectual life.

- Hampson, Norman (1974). The Life and Opinions of Maximilien Robespierre. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-0741-3. Presents three contrasting views

- Linton, Marisa. "Robespierre and the Terror", History Today, August 2006, Volume 56, Issue 8, pp. 23–29 Archived 2007-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- McPhee, Peter (2012). Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300118112.; scholarly biography

- Matrat, Jean. (1971). Robespierre: or the tyranny of the Majority. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. ISBN 0-684-14055-1.

- Palmer, R. R. (1941). Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of Terror in the French Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05119-4. A sympathetic study of the Committee of Public Safety.

- Rudé, George (1976). Robespierre: Portrait of a Revolutionary Democrat. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-60128-4. A Marxist political portrait of Robespierre, examining his changing image among historians and the different aspects of Robespierre as an 'ideologue', as a political democrat, as a social democrat, as a practitioner of revolution, as a politician and as a popular leader/leader of revolution, it also touches on his legacy for the future revolutionary leaders Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-55948-7. A revisionist account.

- Scurr, Ruth. Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. London: Metropolitan Books, 2006 (ISBN 0-8050-7987-4).

- Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine by Hilary Mantel in the London Review of Books, Vol. 28 No. 8, 20 April 2006.

- Reviewed by Sudhir Hazareesingh in the Times Literary Supplement, 7 June 2006.

- Shulim, Joseph I. "Robespierre and the French Revolution," American Historical Review (1977) 82#1 pp. 20–38 in JSTOR

- Soboul, Albert. "Robespierre and the Popular Movement of 1793–4", Past and Present, No. 5. (May 1954), pp. 54–70. in JSTOR

- Tishkoff, Doris (2011). Empire of Beauty. New Haven: Press.

- Thompson, James M. (1988). Robespierre. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-15504-X. Traditional biography with extensive and reliable research.

External links

- Works by Maximilien Robespierre at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Maximilien Robespierre at the Internet Archive

- Maximilien Robespierre Internet Archive on Marxists.org

- Maximilien Robespierre, 1758–1794

- The French Revolution, Robespierre

- Family tree (back to the 18th generation) (also here)

- Remembering the Reign of Terror by Dolan Cummings, Spiked Review of Books, Issue No. 7, November 2007

- A.M.R.I.D (Association Maximilien Robespierre pour l'Idéal Démocratique)(in French)

- 1758 births

- 1794 deaths

- Maximilien de Robespierre

- Deist philosophers

- Deputies to the French National Convention

- Artesian people

- French deists

- French jurists

- French republicans

- Jacobins

- French shooting survivors

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni

- Montagnards

- People from Nord-Pas-de-Calais executed by guillotine during the French Revolution

- People from Arras

- Executed revolutionaries

- Regicides of Louis XVI

- 18th-century French writers

- Critics of Catholicism

- People on the Committee of Public Safety

- People of the Reign of Terror