Biome

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Biomes /ˈbaɪoʊmz/ are climatically and geographically defined as contiguous areas with similar climatic conditions on the Earth, such as communities of plants, animals, soil organisms,[1] and viruses. Some parts of the earth have more or less the same kind of abiotic and biotic factors spread over a large area, creating a typical ecosystem over that area. Such major ecosystems are termed as biomes. Biomes are defined by factors such as plant structures (such as trees, shrubs, and grasses), leaf types (such as broadleaf and needleleaf), plant spacing (such as a forest, woodland, or savanna), and climate. Unlike ecozones, biomes are not defined by genetic, taxonomic, or historical similarities. Biomes are often identified with particular patterns of ecological succession and climax vegetation (quasiequilibrium state of the local ecosystem). An ecosystem has many biotopes and a biome is a major habitat type. A major habitat type, however, is a compromise, as it has an intrinsic inhomogeneity. Some examples of habitats are ponds, trees, streams, creeks, under rocks and burrows in the sand or soil.

The biodiversity characteristic of each extinction, especially the diversity of fauna and subdominant plant forms, is a function of abiotic factors and the biomass productivity of the dominant vegetation. In terrestrial biomes, species diversity tends to correlate positively with net primary productivity, moisture availability, and temperature.[2]

Ecoregions are grouped into both biomes and ecozones.

A fundamental classification of biomes are:

- Terrestrial (land) biomes which includes grassland, tropical rainforest, temperate and tundra

- Aquatic biomes (including freshwater biomes and marine biomes)

Biomes are often known in English by local names. For example, a temperate grassland or shrubland biome is known commonly as steppe in central Asia, prairie in North America, and pampas in South America. Tropical grasslands are known as savanna in Australia, whereas in southern Africa they are known as certain kinds of veld (from Afrikaans).

Sometimes an entire biome may be targeted for protection, especially under an individual nation's biodiversity action plan.

Climate is a major factor determining the distribution of terrestrial biomes. Among the important climatic factors are:

- Latitude: Arctic, boreal, temperate, subtropical, tropical

- Humidity: humid, semihumid, semiarid, and arid

- seasonal variation: Rainfall may be distributed evenly throughout the year or be marked by seasonal variations.

- dry summer, wet winter: Most regions of the earth receive most of their rainfall during the summer months; Mediterranean climate regions receive their rainfall during the winter months.

- Elevation: Increasing elevation causes a distribution of habitat types similar to that of increasing latitude.

The most widely used systems of classifying biomes correspond to latitude (or temperature zoning) and humidity. Biodiversity generally increases away from the poles towards the equator and increases with humidity.

Biome classification schemes

Biomes are defined by climatic parameters. Particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a significant push to understand the relationships between these climatic parameters and properties of ecosystem energetics because such discoveries would enable the prediction of rates of energy capture and transfer among components within ecosystems. Such a study was conducted by Sims et al. (1978) on North American grasslands. The study found a positive logistic correlation between evapotranspiration in mm/yr and above-ground net primary production in g/m2/yr. More general results from the study were that precipitation and water use led to above-ground primary production, solar radiation and temperature lead to below-ground primary production (roots), and temperature and water lead to cool and warm season growth habit.[3] These findings help explain the categories used in Holdridge’s bioclassification scheme (see below), which were then later simplified in Whittaker’s (see below). The number of classification schemes and the variety of determinants used in those schemes, however, should be taken as strong indicators that biomes do not all fit perfectly into the classification schemes created.

Holdridge scheme

In this scheme, climates are classified based on the biological effects of temperature and rainfall on vegetation under the assumption that these two abiotic factors are the largest determinants of the type of vegetation found in an area. Holdridge uses the four axes to define 30 so-called "humidity provinces", which are clearly visible in the Holdridge diagram. While his scheme largely ignores soil and sun exposure, Holdridge did acknowledge that these, too, were important factors in biome determination.

Whittaker's biome-type classification scheme

Whittaker appreciated biome-types as a representation of the great diversity of the living world, and saw the need to establish a simple way to classify them. He based his classification scheme on two abiotic factors: precipitation and temperature. His scheme can be seen as a simplification of Holdridge's, one more readily accessible, but perhaps missing the greater specificity that Holdridge's provides.

Whittaker based his representation of global biomes on both previous theoretical assertions and an ever-increasing empirical sampling of global ecosystems. He was in a unique position to make such a holistic assertion because he had previously compiled a review of biome classification.[4]

Key definitions for understanding Whittaker's scheme

- Physiognomy: The apparent characteristics, outward features, or appearance of ecological communities or species

- Biome: a grouping of terrestrial ecosystems on a given continent that are similar in vegetation structure, physiognomy, features of the environment and characteristics of their animal communities

- Formation: a major kind of community of plants on a given continent

- Biome-type: grouping of convergent biomes or formations of different continents, defined by physiognomy

- Formation-type: a grouping of convergent formations

Whittaker's distinction between biome and formation can be simplified: formation is used when applied to plant communities only, while biome is used when concerned with both plants and animals. Whittaker's convention of biome-type or formation-type is simply a broader method to categorize similar communities.[5]

Whittaker's parameters for classifying biome-types

Whittaker, seeing the need for a simpler way to express the relationship of community structure to the environment, used what he called "gradient analysis" of ecocline patterns to relate communities to climate on a worldwide scale. Whittaker considered four main ecoclines in the terrestrial realm.[5]

- Intertidal levels: The wetness gradient of areas that are exposed to alternating water and dryness with intensities that vary by location from high to low tide

- Climatic moisture gradient

- Temperature gradient by altitude

- Temperature gradient by latitude

Along these gradients, Whittaker noted several trends that allowed him to qualitatively establish biome-types.

- The gradient runs from favorable to extreme, with corresponding changes in productivity.

- Changes in physiognomic complexity vary with the favorability of the environment (decreasing community structure and reduction of stratal differentiation as the environment becomes less favorable).

- Trends in diversity of structure follow trends in species diversity; alpha and beta species diversities decrease from favorable to extreme environments.

- Each growth-form (i.e. grasses, shrubs, etc.) has its characteristic place of maximum importance along the ecoclines.

- The same growth forms may be dominant in similar environments in widely different parts of the world.

Whittaker summed the effects of gradients (3) and (4) to get an overall temperature gradient, and combined this with gradient (2), the moisture gradient, to express the above conclusions in what is known as the Whittaker classification scheme. The scheme graphs average annual precipitation (x-axis) versus average annual temperature (y-axis) to classify biome-types.

Walter system

The Heinrich Walter classification scheme, developed by Heinrich Walter, a German ecologist, differs from both the Whittaker and Holdridge schemes because it takes into account the seasonality of temperature and precipitation. The system, also based on precipitation and temperature, finds 9 major biomes, with the important climate traits and vegetation types summarized in the accompanying table. The boundaries of each biome correlate to the conditions of moisture and cold stress that are strong determinants of plant form, and therefore the vegetation that defines the region. Extreme conditions, such as flooding in a swamp, can create different kinds of communities within the same biome.

- I: Equatorial

- Always moist and lacking temperature seasonality

- Evergreen tropical rain forest

- II: Tropical

- Summer rainy season and cooler “winter” dry season

- Seasonal forest, scrub, or savanna

- III: Subtropical

- Highly seasonal, arid climate

- Desert vegetation with considerable exposed surface

- IV: Mediterranean

- Winter rainy season and summer drought

- Sclerophyllous (drought-adapted), frost-sensitive shrublands and woodlands

- V: Warm temperate

- Occasional frost, often with summer rainfall maximum

- Temperate evergreen forest, somewhat frost-sensitive

- VI: Nemoral

- Moderate climate with winter freezing

- Frost-resistant, deciduous, temperate forest

- VII: Continental

- Arid, with warm or hot summers and cold winters

- Grasslands and temperate deserts

- VIII: Boreal

- Cold temperate with cool summers and long winters

- Evergreen, frost-hardy, needle-leaved forest (taiga)

- IX: Polar

- Very short, cool summers and long, very cold winters

- Low, evergreen vegetation, without trees, growing over permanently frozen soils

Bailey system

Robert G. Bailey almost developed a biogeographical classification system for the United States in a map published in 1976. He subsequently expanded the system to include the rest of North America in 1981, and the world in 1989. The Bailey system, based on climate, is divided into seven domains (polar, humid temperate, dry, humid, and humid tropical), with further divisions based on other climate characteristics (subarctic, warm temperate, hot temperate, and subtropical; marine and continental; lowland and mountain).[6]

- 100 Polar Domain

- 200 Humid Temperate Domain

- 210 Warm Continental Division (Köppen: portion of Dcb)

- M210 Warm Continental Division – Mountain Provinces

- 220 Hot Continental Division (Köppen: portion of Dca)

- M220 Hot Continental Division – Mountain Provinces

- 230 Subtropical Division (Köppen: portion of Cf)

- M230 Subtropical Division – Mountain Provinces

- 240 Marine Division (Köppen: Do)

- M240 Marine Division – Mountain Provinces

- 250 Prairie Division (Köppen: arid portions of Cf, Dca, Dcb)

- 260 Mediterranean Division (Köppen: Cs)

- M260 Mediterranean Division – Mountain Provinces

- 300 Dry Domain

- 310 Tropical/Subtropical Steppe Division

- M310 Tropical/Subtropical Steppe Division – Mountain Provinces

- 320 Tropical/Subtropical Desert Division

- 330 Temperate Steppe Division

- 340 Temperate Desert Division

- 400 Humid Tropical Domain

- 410 Savanna Division

- 420 Rainforest Division

WWF system

A team of biologists convened by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) developed an ecological land classification system that identified fourteen biomes,[7] called major habitat types, and further divided the world's land area into 882 terrestrial ecoregions (includes new Antarctic ecoregions by Terrauds et al. 2012). Each terrestrial ecoregion has a specific EcoID, format XXnnNN (XX is the ecozone, nn is the biome number, NN is the individual number). This classification is used to define the Global 200 list of ecoregions identified by the WWF as priorities for conservation. The WWF major habitat types are:

- 01 Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests (tropical and subtropical, humid)

- 02 Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests (tropical and subtropical, semihumid)

- 03 Tropical and subtropical coniferous forests (tropical and subtropical, semihumid)

- 04 Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests (temperate, humid)

- 05 Temperate coniferous forests (temperate, humid to semihumid)

- 06 Boreal forests/taiga (subarctic, humid)

- 07 Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands (tropical and subtropical, semiarid)

- 08 Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands (temperate, semiarid)

- 09 Flooded grasslands and savannas (temperate to tropical, fresh or brackish water inundated)

- 10 Montane grasslands and shrublands (alpine or montane climate)

- 11 Tundra (Arctic)

- 12 Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub or sclerophyll forests (temperate warm, semihumid to semiarid with winter rainfall)

- 13 Deserts and xeric shrublands (temperate to tropical, arid)

- 14 Mangrove (subtropical and tropical, salt water inundated)

Freshwater biomes

According to the WWF, the following are classified as freshwater biomes:[8]

|

|

- Streams and rivers

Realms or ecozones (terrestrial and freshwater, WWF)

|

|

Marine biomes

Marine biomes (H) (major habitat types), Global 200 (WWF)

Biomes of the coastal and continental shelf areas (neritic zone – List of ecoregions (WWF))

- Polar

- Temperate shelves and sea

- Temperate upwelling

- Tropical upwelling

- Tropical coral[9]

Realms or ecozones (marine, WWF)

|

|

Other marine habitat types

- Hydrothermal vents

- Cold seeps

- Benthic zone

- Pelagic zone (trades and westerlies)

- Abyssal

- Hadal (ocean trench)

Major habitats, nonglobal 200 (WWF)

Summary – ecological taxonomy (WWF)

- Biomsphere (List of ecoregions)

- Ecozones or realms (8)

- Terrestrial biomes (major habitat types, 14)

- Ecoregions (867) vbn,

- Freshwater biomes (major habitat types, 12)

- Ecoregions (426)

- Ecosystems (biotopes)

- Ecoregions (426)

- Terrestrial biomes (major habitat types, 14)

- Marine ecozones or realms (13)

- Continental Shelf biomes (major habitat types, 5)

- (Marine provinces) (62)

- Ecoregions (232)

- Ecosystems (biotopes)

- Ecoregions (232)

- (Marine provinces) (62)

- Open & Deep Sea Biomes (major habitat types)

- Continental Shelf biomes (major habitat types, 5)

- Endolithic biome

- Ecozones or realms (8)

Example

- Biosphere

- Ecozone: Palearctic ecozone

- Terrestrial biome: temperate broadleaf and mixed forests

- Ecoregion: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests (PA0418)

- Ecosystem: Orjen, vegetation belt between 1,100–1,450 m, Oromediterranean zone, nemoral zone (temperate zone)

- Biotope: Oreoherzogio-Abietetum illyricae Fuk. (Plant list)

- Plant: Silver fir (Abies alba)

- Biotope: Oreoherzogio-Abietetum illyricae Fuk. (Plant list)

- Ecosystem: Orjen, vegetation belt between 1,100–1,450 m, Oromediterranean zone, nemoral zone (temperate zone)

- Ecoregion: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests (PA0418)

- Terrestrial biome: temperate broadleaf and mixed forests

- Ecozone: Palearctic ecozone

Anthropogenic biomes

Humans have altered global patterns of biodiversity and ecosystem processes. As a result, vegetation forms predicted by conventional biome systems can no longer be observed across much of Earth's land surface as they have been replaced by crop and rangelands or cities. Anthropogenic biomes provide an alternative view of the terrestrial biosphere based on global patterns of sustained direct human interaction with ecosystems, including agriculture, human settlements, urbanization, forestry and other uses of land. Anthropogenic biomes offer a new way forward in ecology and conservation by recognizing the irreversible coupling of human and ecological systems at global scales and moving us toward an understanding of how best to live in and manage our biosphere and the anthropogenic biomes we live in.

Major anthropogenic biomes

- Dense settlements

- Croplands

- Rangelands

- Forested

- Indoor[10]

Other biomes

The endolithic biome, consisting entirely of microscopic life in rock pores and cracks, kilometers beneath the surface, has only recently been discovered, and does not fit well into most classification schemes.

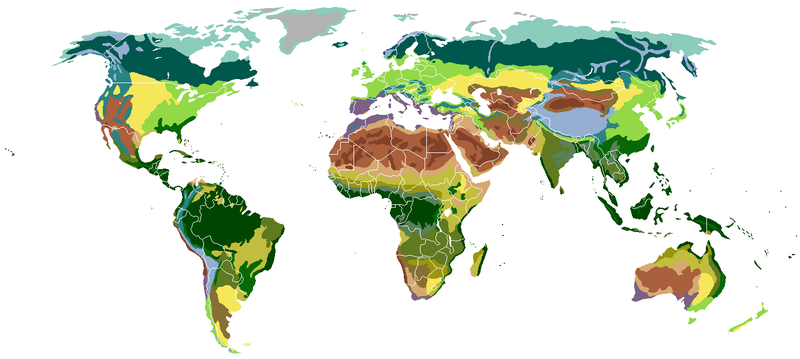

Map of biomes

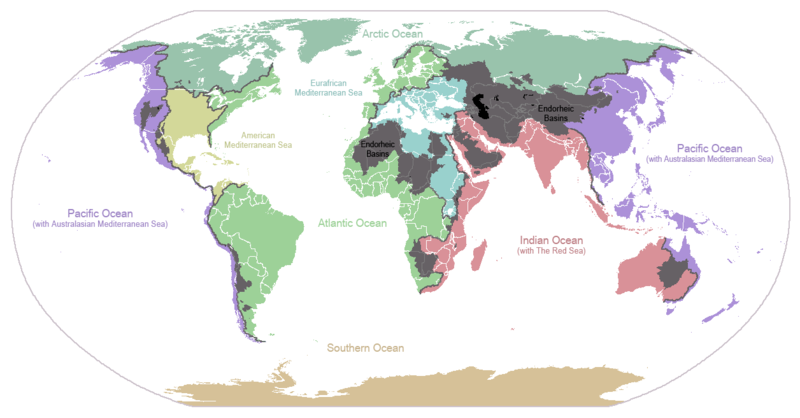

Freshwater biomes

The drainage basins of the principal oceans and seas of the world are marked by continental divides. The grey areas are endorheic basins that do not drain to the ocean.

See also

- Altitudinal zonation

- Biomics

- Biosphere reserve

- Earth Science

- Ecology

- Ecosystem

- Ecosystem diversity

- Ecotope

- Climate classification

- Effect of climate change on plant biodiversity

- Gene pool

- Genetic pollution

- Genetic erosion

- Growing region

- Human microbiome

- A.W. Kuchler

- Life zones

- Natural environment

- Nature

- Pedology (soil study)

- Pliocene

- World Network of Biosphere Reserves

References

- ^ The World's Biomes, Retrieved August 19, 2008, from University of California Museum of Paleontology

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006-10-16). "Biomes". In Sidney Draggan (ed.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ Pomeroy, Lawrence R. and James J. Alberts, editors. Concepts of Ecosystem Ecology. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1988.

- ^ Whittaker, Robert H., Botanical Review, Classification of Natural Communities, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan–Mar 1962), pp. 1–239.

- ^ a b Whittaker, Robert H. Communities and Ecosystems. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, Inc., 1975.

- ^ http://www.fs.fed.us/land/ecosysmgmt/index.html Bailey System, US Forest Service

- ^ Olson et al. (2001); Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth, BioScience, Vol. 51, No. 11., pp. 933–938.

- ^ "Freshwater Ecoregions of the World: Major Habitat Types" [1]. Accessed May 12, 2008.

- ^ WWF: Marine Ecoregions of the World

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (March 19, 2015). "The Next Frontier: The Great Indoors". New York Times. Retrieved March 2015.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help)

External links

- Biomes of the world (Missouri Botanic Garden)

- Global Currents and Terrestrial Biomes Map

- WorldBiomes.com is a site covering the 5 principal world biome types: aquatic, desert, forest, grasslands, and tundra.

- UWSP's online textbook The Physical Environment: – Earth Biomes

- Panda.org's Habitats – describes the 14 major terrestrial habitats, 7 major freshwater habitats, and 5 major marine habitats.

- Panda.org's Habitats Simplified – provides simplified explanations for 10 major terrestrial and aquatic habitat types.

- UCMP Berkeley's The World's Biomes – provides lists of characteristics for some biomes and measurements of climate statistics.

- Gale/Cengage has an excellent Biome Overview of terrestrial, aquatic, and man-made biomes with a particular focus on trees native to each, and has detailed descriptions of desert, rain forest, and wetland biomes.

- NASA's Earth Observatory Mission: Biomes gives an exemplar of each biome that is described in detail and provides scientific measurements of the climate statistics that define each biome.