World Wireless System

It has been suggested that Magnifying transmitter be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since February 2015. |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

World Wireless System was a proposed turn of the 19th century telecommunications, and electrical power transmission and distribution system designed by inventor Nikola Tesla based on his theories of using Earth and its atmosphere as electrical conductors. Tesla claimed this system would allow for "the transmission of electric energy without wires on a global scale[1] for point-to-point wireless telecommunications, broadcasting and industrial power transmision. He made public statements citing two related methods to accomplish this from the mid-1890s on. By the end of 1900 Tesla had convinced banker J. P. Morgan to finance construction of a wireless station (eventually sited at Wardenclyffe) based on his ideas intended to transmit messages across the Atlantic to England and to ships at sea. Almost as soon as the contract was signed Tesla decided to scale up the facility to include his ideas of terrestrial wireless power transmission to better compete with Guglielmo Marconi's radio based telegraph system.[2] Morgan refused to fund the changes and, when no additional investment capital became available, the project at Wardenclyffe was abandoned in 1906, never to become operational.

During this period Tesla filed numerous patents associated with the basic functions of his system, including transformer design, transmission methods, tuning circuits, and methods of signaling. He also described a plan to have some thirty Wardenclyffe-style telecommunications stations positioned around the world to be tied into existing telephone and telegraph systems. Tesla would continue to elaborate to the press and in his writings for the next few decades on the system's capability's and how it was superior to radio-based systems.

Despite Tesla's claims that he had "carried on practical experiments in wireless transmission"[3] there is no documentation he ever transmitted power beyond relatively short distances, and modern scientific opinion is that his wireless power scheme would not have worked.

History

Origins

Tesla's idea's for a world wireless system grew out of experiments beginning in the early 1890s after learning of Hertz's experiments with electromagnetic waves using induction coil transformers and spark gaps.[7][8] He duplicated those experiments and then went on to improve Hertz's wireless transmitter, developing various alternator apparatus and his own high tension transformer, known as the Tesla coil.[9][10] Tesla's primary interest in wireless phenomenon was as a power distribution system, early on pursuing wireless lighting.[11] From 1891 on Tesla was delivering lectures including "Experiments with Alternate Currents of High Potential and High Frequency" in 1892 in London and in Paris and went on to demonstrate "wireless lighting"[12] in 1893[13] including lighting Geissler tubes wirelessly.

One-wire transmission

The first experiment was the operation of light and motive devices connected by a single wire to one terminal of a high frequency induction coil, performed during the 1891 New York City lecture at Columbia College. While a single terminal incandescent lamp connected to one of an induction coil’s secondary terminals does not form a closed circuit “in the ordinary acceptance of the term”[14] the circuit is closed in the sense that a return path is established back to the secondary by capacitive coupling or 'displacement current'. This is due to the lamp’s filament or refractory button capacitance relative to the coil’s free terminal and environment; the free terminal also has capacitance relative to the lamp and environment.

Wireless transmission

The second result demonstrated how energy can be made to go through space without any connecting wires. The wireless energy transmission effect involves the creation of an electric field between two metal plates, each being connected to one terminal of an induction coil’s secondary winding. A gas discharge tube) was used as a means of detecting the presence of the transmitted energy. Some demonstrations involved lighting of two partially evacuated tubes in an alternating electrostatic field while held in the hand of the experimenter.[15]

In his wireless transmission lectures Tesla proposed the technology could include the telecommunication of information.

Development

Tesla (like many scientists of that time[16]) thought, even if radio waves existed, they would probably only travel in straight lines making them useless for long range transmission. He theorized that transmitting electrical signals any distance would have to use the planet Earth or some other medium to overcome this limitation.[17] By the end of 1895 he was making statements to the press on the possibility that "earth's electrical charge can be disturbed, and thereby electrical waves can be efficiently transmitted to any distance without the use of cables or wires" to transmit "intelligible signals" and "motive power".[18] In April 11, 1896 Tesla made another statement that he believed, "messages might be conducted to all parts of the globe simultaneously" using electric waves "propagated through the atmosphere and even the ether beyond".[19] In September of 1897 he applied for a patent[20] on a wireless power transmission scheme consisting of transmitting power between two tethered balloons maintained at 30,000 feet, an altitude where he thought a conductive layer should exist.[21]

Between 1895 - 1898 Tesla constructed a large resonance transformer in his New York City lab called a magnifying transmitter to test his earth conduction theories.[22] In 1899 he conducted large scale experiments at Colorado Springs, Colorado. From his measurements there he concluded the Earth was "literally alive with electrical vibrations." He noted that lightning strikes seemed to show the Earth was indeed a big conductor with the waves of energy from each strike going from one side of the Earth to the other. At Colorado Springs he also constructed a large magnifying transmitter measuring fifty-one feet (15.5 m) in diameter which could develop a working potential estimated at 3.5 million to 4 million volts and was capable of producing electrical discharges exceeding one hundred feet (30 m) in length.[23] With it he tested earth conduction and lit un-connected electric lights outside his lab in demonstrations of wireless power transmission at relatively short ranges.

After Tesla returned to New York City from Colorado Springs in 1900 he sought venture capitalists to fund what he thought was revolutionary wireless communication and electric power delivery system using the Earth as the conductor. At the end of 1900 he gained the attention of financier J. P. Morgan who agreed to fund a pilot project (later to become the Wardenclyffe project) which, based on Tesla's theories, would be capable of transmitting messages, telephony, and even facsimile images across the Atlantic to England and to ships at sea. Morgan was to receive a controlling share in the company as well as half of all the patent income. Tesla's decision in July 1901 to include his ideas of wireless power transmission to better compete with Guglielmo Marconi's new radio based telegraph system was met with Morgan's refusal to fund the changes.

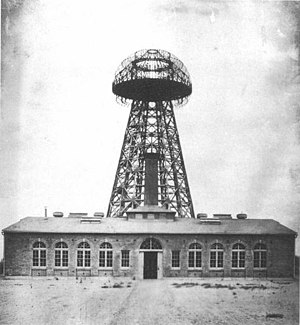

Construction of the Wardenclyffe "wireless plant" in Shoreham started towards the end of 1901 and continued for the next three years. The plant included a Stanford White designed 94 by 94 ft (29 by 29 m) brick building, a wood-framed tower 186 feet (57 m) tall with a 68 feet (21 m) in diameter "cupola" on top, and a 120 feet (37 m) shaft sunk into the ground with sixteen iron pipes driven "one length after another" 300 feet (94.4 m) below the shaft in order for the machine, in Tesla's words, "to have a grip on the earth so the whole of this globe can quiver."[26][27] Funding problems continued to plague Wardenclyffe and by 1905-1906 most of the site's activity had to be shut down.

Elements

U.S. patent 1,119,732

Through the latter part of the 1890s and during the construction of Wardenclyffe, Tesla applied for patents covering the many elements that would make up his wireless system. The system Tesla came up with was based on electrical conduction with an electrical charge being conducted through the ground and being returned through the air.[28] It consisted of a grounded Tesla coil as a resonance transformer transmitter that he theorized would be able to create a displacement of Earth's electric charge by alternately charging and discharging the oscillator's elevated terminal. This would work in conjunction with a second Tesla coil used in receive mode at a distant location, also with a grounded helical resonator and an elevated terminal.[29][30][31] Tesla believed that the placement of a grounded resonance transformer at another point on the Earths surface in the roll of a receiver tuned to the same frequency as the transmitter would allow electric current flowing through the Earth between the two. He also believed waves of electric current from the sending tower would reflect back from the far side of the globe, resulting in amplified wave pattern of electric current that he could direct to any point on the globe, localizing power delivery directly to the receiving station. The other part of his system was electricity returned via "an equivalent electric displacement""[32] in the atmosphere via a charged conductive upper layer that Tesla thought existed,[33][28] a theory dating back to an 1872 idea for a proposed wireless power system by Mahlon Loomis.[34] The current could be used at the receiver to drive electrical devices.[30]

Tesla told a friend his plans included the building of more than thirty transmission-reception stations constructed near major population centers around the world[35] with Wardenclyffe being the first. If plans had moved forward without interruption the Long Island prototype would have been followed by a second plant built in the British Isles, perhaps on the west coast of Scotland near Glasgow. Each of these facilities was to include a large magnifying transmitter of a design loosely based upon the apparatus assembled at the Colorado Springs experimental station in 1899.[36]

Proposed theories of operation

Terrestrial surface waves

This is a predicted geo-physical manifestation of electromagnetic wave energy related to a persistent single-conductor surface wave electrical transmission line phenomenon called the Zenneck wave.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] The Zenneck wave is an exact solution to Maxwell's equations. It is supported by a planar or spherical interface between two homogeneous media having different dielectric constants. In the case of the terrestrial Zenneck wave, the upper medium is the insulating atmosphere and the lower medium is the earth below it, comprising a lossy spherical conducting transmission line. Propagation across Earth's surface is by virtue of its high conductivity. Tesla claimed discovery of this geo-electrical phenomenon, which, he said, would allow for the global transmission of electrical energy.

That communication without wires to any point of the globe is practicable with such apparatus would need no demonstration, but through a discovery which I made I obtained absolute certitude. Popularly explained, it is exactly this: When we raise the voice and hear an echo in reply, we know that the sound of the voice must have reached a distant wall, or boundary, and must have been reflected from the same. Exactly as the sound, so an electrical wave is reflected, and the same evidence which is afforded by an echo is offered by an electrical phenomenon known as a "stationary" wave — that is, a wave with fixed nodal and ventral regions. Instead of sending sound-vibrations toward a distant wall, I have sent electrical vibrations toward the remote boundaries of the earth, and instead of the wall the earth has replied. In place of an echo I have obtained a stationary electrical wave, a wave reflected from afar.[46]

The terrestrial stationary wave claimed by Tesla forms the basis of his proposed World Wireless system, designed for the purposes of point-to-point telecommunications, broadcasting, and, ultimately, the transmission of electrical power.

The discovery of the stationary terrestrial waves, showing that, despite its vast extent, the entire planet can be thrown into resonant vibration like a little tuning fork; that electrical oscillations suited to its physical properties and dimensions pass through it unimpeded, in strict obedience to a simple mathematical law, has proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that the earth, considered as a channel for conveying electrical energy, even in such delicate and complex transmissions as human speech or musical composition, is infinitely superior to a wire or cable, however well designed.[47]

It remains an unanswered question as to whether the Zenneck wave whole Earth resonance modes described by Tesla can be excited.

Schumann resonance hypothesis

It has been suggested this phenomenon arises in the Earth's interior space because of the conductive ionosphere's action as a waveguide. The limited dimensions of the earth cause this waveguide to act as a resonant cavity for electromagnetic waves. The cavity is naturally excited by energy from lightning strikes. The Schumann Resonance is a set of terrestrial stationary waves in the extremely low frequency (ELF) portion of the Earth's electromagnetic field spectrum. Lower frequencies and those at or below longwave bands travel most efficiently as a longitudinal wave and create stationary waves. The ionosphere and the Earth's surface constitute an interface that supports the wave. This resonant cavity is a particular standing wave pattern formed by waves confined in the cavity. The waves correspond to the wavelengths which are reinforced by constructive interference after many reflections from the cavity's reflecting surfaces.

The transfer of electrical energy with small losses in this manner is problematic because the standing wave would occur in the earth-ionosphere cavity, which is too lossy to enable a standing wave of sufficient amplitude to be generated. This limitation is independent of the power of the transmitter. In order for the transmitter to feed power to the receiver as efficiently as it would in a closed low-loss circuit, the power transferred to the receiver should be able to transfer power of the same order of magnitude reciprocally back to the transmitter. This is a necessary condition for the transmitter to “feel” the load connected to the receiver and to supply power to it via the standing wave. In order to do this, the required Q of the earth-ionosphere cavity would have to be on the order of 106 or so at the lowest Schumann frequency of about 7.3 Hz. Measurements based on the spectrum of natural electrical radio noise yield a Q of only about 5 to 10. [Henry Bradford]

Regarding this recent notion of power transmission through the earth-ionosphere cavity, a consideration of the earth-ionosphere or concentric spherical shell waveguide propagation parameters as they are known today shows that wireless power transmission by direct excitation of a Schumann cavity resonance mode is not realizable.[48]

The conceptual difficulty with this model is that, at the very low frequencies that Tesla said that he employed (1-50 kHz), earth-ionosphere waveguide excitation, now well understood, would seem to be impossible with the either the Colorado Springs or the Long Island apparatus (at least with the apparatus that is visible in the photographs of these facilities).[49]

Furthermore, the maximum recommended operating frequencies of 25 kHz as specified by Tesla is far above the highest easily observable Schumann resonance mode (the 9th overtone) that exists at approximately 66.4 Hz. Tesla's selection of 25 kHz is wholly inconsistent with the operation of a system that is based upon the direct excitation of a Schumann resonance mode.

Claimed applications

Tesla description of his wireless transmission ideas in 1895 include its humanitarian uses in bringing abundant electrical energy to remote underdeveloped parts of the world and fostering closer communications amongst nations.[50] His June, 1900 Century Magazine article "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy" includes photographs of his Colorado Springs experiments and his thoughts on how Hertz experiments were not "an experimental verification of the poetical conceptions of Maxwell." He elaborated on his system of using Earth as the medium for wireless telecommunication and power delivery. He wrote how he could set up communications at any distance. He noted his system could localize electrical delivery to a point on the globe via stationary waves. He also noted this same process could be used to locate maritime objects such as icebergs or ships at sea.

In 1909 Tesla stated:

- "It will soon be possible, for instance, for a business man in New York to dictate instructions and have them appear instantly in type in London or elsewhere. He will be able to call up from his desk and talk with any telephone subscriber in the world. It will only be necessary to carry an inexpensive instrument not bigger than a watch, which will enable its bearer to hear anywhere on sea or land for distances of thousands of miles. One may listen or transmit speech or song to the uttermost parts of the world."[51][52]

Tesla also believed that high potential electric current flowing through the upper atmosphere could make it glow, providing night time lighting for transoceanic shipping lanes.[34]

Tesla elaborated on his world wireless system in his 1919 Electrical Experimenter article titled "The True Wireless," detailing its ability for long range telecommunications and putting forward his view that the prevailing theory of radio wave propagation was inaccurate.[53][54]

- "The Hertz wave theory of wireless transmission may be kept up for a while, but I do not hesitate to say that in a short time it will be recognized as one of the most remarkable and inexplicable aberrations of the scientific mind which has ever been recorded in history."

Feasibility

Tesla demonstrated wireless power transmission at Colorado Springs, lighting incandescent electric lamps positioned relatively close to the structure housing his large experimental magnifying transmitter[55] and claimed afterwards that he had, "carried on practical experiments in wireless transmission."[56] He believed having achieved Earth electrical resonance at Colorado Springs that, according to his theory, can produce electrical effects at any terrestrial distance.[57]

There is no documented evidence Tesla ever transmitted significant power beyond the short-range demonstrations[25] [58] [59] [60] [61] [62] [63] [64] [65] reaching "far out into the field," [66] perhaps 300 feet (91 m). Modern statements of opinion exist that the wireless power transmission component of his plan would not have worked.[58][59][63][65] [67][68] [69] [70] [71] The only known report of long-distance telecommunications by means of his system for the transmission and reception of electrical energy by Tesla himself is from a 1916 legal deposition, stating that in 1899 he collected quantitative transmission-reception data at a distance of about 10 miles (16 km).[72]

Related patents

- SYSTEM OF ELECTRIC LIGHTING, April 25, 1891, U.S. patent 454,622, June 23, 1891.

- MEANS FOR GENERATING ELECTRIC CURRENTS, August 2, 1893, U.S. patent 514,168, February 6, 1894.

- ELECTRICAL TRANSFORMER, March 20, 1897, U.S. patent 593,138, November 2, 1897.

- METHOD AND APPARATUS FOR CONTROLLING MECHANISM OF MOVING VESSEL OR VEHICLES, July 1, 1898, U.S. patent 613,809 November 8, 1898.

- SYSTEM OF TRANSMISSION OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY, September 2, 1897, U.S. patent 645,576, March 20, 1900.

- APPARATUS FOR TRANSMISSION OF ELECTRICAL ENERGY, September 2, 1897, U.S. patent 649,621, May 15, 1900.

- METHOD OF INTENSIFYING AND UTILIZING EFFECTS TRANSMITTED THROUGH NATURAL MEDIA, June 24, 1899, U.S. patent 685,953, November 5, 1901.

- METHOD OF UTILIZING EFFECTS TRANSMITTED THROUGH NATURAL MEDIA, August 1, 1899, U.S. patent 685,954, November 5, 1901.

- APPARATUS FOR UTILIZING EFFECTS TRANSMITTED FROM A DISTANCE TO A RECEIVING DEVICE THROUGH NATURAL MEDIA, June 24, 1899, U.S. patent 685,955, November 5, 1901.

- APPARATUS FOR UTILIZING EFFECTS TRANSMITTED THROUGH NATURAL MEDIA, March 21, 1900, U.S. patent 685,956, November 5, 1901.

- METHOD OF SIGNALING, July 16, 1900, U.S. patent 723,188, March 17, 1903.

- SYSTEM OF SIGNALING, July 16, 1900, U.S. patent 725,605, April 14, 1903.

- ART OF TRANSMITTING ELECTRICAL ENERGY THROUGH THE NATURAL MEDIUMS, May 16, 1900, U.S. patent 787,412, April 18, 1905.

- ART OF TRANSMITTING ELECTRICAL ENERGY THROUGH THE NATURAL MEDIUMS, April 17, 1906, Canadian Patent 142,352, August 13, 1912.

- APPARATUS FOR TRANSMITTING ELECTRICAL ENERGY, January 18, 1902, U.S. patent 1,119,732, December 1, 1914.

See also

- Wireless energy transmission

- Surface wave

- Surface plasmon

- Surface-wave-sustained mode

- Transmission medium

- Distributed generation

- Electricity distribution

- Electric power transmission

- Apparatus

Notes

- ^ "The Transmission of Electric Energy Without Wires," Electrical World, March 5, 1904". 21st Century Books. 5 March 1904. Retrieved 4 June 2009.."

- ^ Marc J. Seifer, Nikola Tesla: The Lost Wizard, from: ExtraOrdinary Technology (Volume 4, Issue 1; Jan/Feb/Mar 2006)

- ^ Electrocraft - Volume 6 - 1910, Page 389

- ^ Electrical Experimenter, January 1919. pg. 615

- ^ Cheney, Margaret, Tesla: Man Out of Time, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1981, p. 174.

- ^ Norrie, H. S., Induction Coils: How to make, use, and repair them. Norman H. Schneider, 1907, New York. 4th edition.

- ^ James O'Neill, Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla, page 86

- ^ Marc Seifer, Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla - page 1721

- ^ "Nikola Tesla". ieeeghn.org

- ^ U.S. patent 447,921, Tesla, Nikola, "Alternating Electric Current Generator".

- ^ Radio: Brian Regal, The Life Story of a Technology, page 22

- ^ W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press - 2013, page 132

- ^ note: at St. Louis, Missouri, Tesla public demonstration called, "On Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena", Journal of the Franklin Institute, Volume 136 By Persifor Frazer, Franklin Institute (Philadelphia, Pa)

- ^ Martin, Thomas Commerford, "The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla", The Electrical Engineer, New York, 1894; "On Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena," February 24, 1893, before the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, March 1893, before the National Electric Light Association, St. Louis.

- ^ Martin, Thomas Commerford, "The Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla", The Electrical Engineer, New York, 1894; "Experiments With Alternating Currents of Very High Frequency, and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination," AIEE, Columbia College, N.Y., May 20, 1891.

- ^ Brian Regal, Radio: The Life Story of a Technology, page 22

- ^ earlyradiohistory.us, Thomas H. White, Nikola Tesla: The Guy Who DIDN'T "Invent Radio", November 1, 2012

- ^ "Tesla on Electricity Without Wires," Electrical Engineer - N. Y., Jan 8, 1896, p 52. (Refers to letter by Tesla in the NEW YORK HERALD, 12/31/1895.)

- ^ MINING & SCIENTIFIC PRESS, "Electrical Progress" Nikola Tesla Is Credited With Statement", April 11, 1896

- ^ U.S. Patents number 645,576 and 649,621

- ^ Carol Dommermuth-Costa, Nikola Tesla: A Spark of Genius, Twenty-First Century Books, 1994, page 85-86

- ^ My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla, Hart Brothers, 1982, Ch. 5, ISBN 0-910077-00-2

- ^ Nikola Tesla: Guided Weapons & Computer Technology, Leland I. Anderson, 21st Century Books, 1998, pp. 12-13, ISBN 0-9636012-9-6.

- ^ a b Tesla, Nikola (2002). Nikola Tesla on His Work with Alternating Currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power: An Extended Interview. 21st Century Books. pp. 96–97. ISBN 1893817016.

- ^ a b Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4655-9. Cite error: The named reference "Carlson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Nikola Tesla On His Work With Alternating Currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power, ISBN 1-893817-01-6, p. 203

- ^ Margaret Cheney, Robert Uth, Jim Glenn, Tesla, Master of Lightning, Barnes & Noble Publishing - 1999, page 100

- ^ a b W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press - 2013, page 210

- ^ Seifer, Marc J., Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla. p. 228.

- ^ a b Ratzlaff, John T., Dr. Nikola Tesla Complete Patents; System of Transmission of Electrical Energy, September 2, 1897, U.S. patent 645,576, March 20, 1900.

- ^ Tesla, Nikola, "The True Wireless". Electrical Experimenter, May 1919. (Available at pbs.org)

- ^ Ratzlaff, John T., Tesla Said, Tesla Book Company, 1984; "The Disturbing Influence of Solar Radiation On the Wireless Transmission of Energy," Electrical Review and Western Electrician, July 6, 1912

- ^ Carol Dommermuth-Costa, Nikola Tesla: A Spark of Genius, Twenty-First Century Books, 1994, page 85-86

- ^ a b Thomas H. White, Nikola Tesla: The Guy Who DIDN'T "Invent Radio",earlyradiohistory.us, November 2012

- ^ Seifer, Marc J., Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla. p. 472. (cf. "Each tower could act as a sender or a receiver. In a letter to Katherine Johnson, Tesla explains the need for well over thirty such towers".)

- ^ Nikola Tesla On His Work with Alternating Currents and Their Application to wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power, 21st Century Books, 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Sommerfeld, Arnold N., “Uber die Ausbreitung der Wellen in der drahtlosen Telegraphie,” Annalen der Physik, March 16, 1909 (Vol. 28, No. 4), pp. 665-736.

- ^ Zenneck, Jonathan, “Uber die Fortpflanzung ebener elektro-magnetischer Wellen langs einer ebenen Leiterflache und ihre Beziehung zur drahtlosen Telegraphie,” Annalen der Physik, Vol. 23, September 20, 1907, pp. 846-866.

- ^ Wait, J. R., "Electromagnetic Surface Waves," in Advances in Radio Research, J.A Saxton, editor, Academic Press, Vol. 1, 1964, pp. 157-217. (See Corrections in Radio Science, Vol. 69D, #1, 1965, pp. 969-975.)

- ^ Goubau, G., “Über die Zennecksche Bodenwelle,” (On the Zenneck Surface Wave), Zeitschrift fur Angewandte Physik, Vol. 3, 1951, Nrs. 3/4, pp. 103-107.

- ^ Kistovich, Y. V. "Possibility of Observing Zenneck Surface Waves in Radiation from a Source with a Small Vertical Aperture," Soviet Physics Technical Physics, Vol. 34, No. 4, April, 1989, pp. 391-394.

- ^ Baibakov, V. I., V. N. Datsko, Y. V. Kistovich, "Experimental discovery of Zenneck's surface electromagnetic waves," Soviet Physics Uspekhi, 1989, 32 (4), pp. 378-379.

- ^ Corum, K. L. and J. F. Corum, “Nikola Tesla, Lightning Observations, and Stationary Waves,” Appendix II, "The Zenneck Surface Wave," 1994

- ^ Barlow, H., J. Brown, Radio Surface Waves, Oxford University Press, London, 1962.

- ^ Hendry, Janice, “Surface Waves: What are they? Why are they interesting?,” Roke Manor Research Ltd., 2009.

- ^ THE PROBLEM OF INCREASING HUMAN ENERGY, Century Magazine, June 1900

- ^ TUNED LIGHTNING, English Mechanic and World of Science, March 8, 1907, pp. 107, 108

- ^ Bradford, Henry, "Nikola Tesla On Wireless Energy Transmission" The Schumann Cavity Resonance Hypothesis.

- ^ Spherical Transmission Lines and Global Propagation, An Analysis of Tesla's Experimentally Determined Propagation Model, K. L. Corum, J. F. Corum, Ph.D., and J. F. X. Daum, Ph.D. 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Nikola Tesla, Letter: Electricity Without Wires, NEW YORK HERALD,01/01/1896

- ^ Gilbert King, The Rise and Fall of Nikola Tesla and his Tower, smithsonian.com, February 4, 2013

- ^ Wireless of the Future, Popular Mechanics Oct 1909

- ^ Gregory Malanowski, The Race for Wireless, AuthorHouse - 2011, page 36

- ^ earlyradiohistory.us, Thomas H. White, Nikola Tesla: The Guy Who DIDN'T "Invent Radio", November 1, 2012

- ^ recorded in the "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy" article published in Century Magazine, June 1900

- ^ Electrocraft - Volume 6 - 1910, Page 389

- ^ W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press - 2013, page 301

- ^ a b Coe, Lewis (2006). Wireless Radio: A History. McFarland. p. 112. ISBN 0786426624.

- ^ a b Wheeler, L. P. (August 1943). "Tesla's contribution to high frequency". Electrical Engineering. 62 (8). IEEE: 355–357. doi:10.1109/EE.1943.6435874. ISSN 0095-9197.

- ^ Cheney, Margaret; Uth, Robert; Glenn, Jim (1999). Tesla, Master of Lightning. Barnes & Noble Publishing. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0760710058.

- ^ Brown, William C. (1984). "The history of power transmission by radio waves". MTT-Trans. on Microwave Theory and Technique. 32 (9). Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers: 1230–1234. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Dunning, Brian (January 15, 2013). "Did Tesla plan to transmit power world-wide through the sky?". The Cult of Nikola Tesla. Skeptoid.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Tomar, Anuradha; Gupta, Sunil (July 2012). "Wireless power Transmission: Applications and Components". International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology. 1 (5). ISSN 2278-0181. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ "Life and Legacy: Colorado Springs". Tesla: Master of Lightning - companion site for 2000 PBS television documentary. PBS.org, US Public Broadcasting Service website. 2000. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b Shinohara, Naoki (2014). Wireless Power Transfer via Radiowaves. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 1118862961.

- ^ 2 Jan, 1899, ‘‘Nikola Tesla Colorado Springs Notes 1899–1900’’, Nolit, 1978, p. 353.

- ^ Broad, William J. (May 4, 2009). "A Battle to Preserve a Visionary's Bold Failure". New York Times. New York: The New York Times Co. pp. D1. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ Wearing, Judy (2009). Edison's Concrete Piano: Flying Tanks, Six-Nippled Sheep, Walk-On-Water Shoes, and 12 Other Flops From Great Inventors. ECW Press. p. 98. ISBN 1554905516.

- ^ Curty, Jari-Pascal; Declercq, Michel; Dehollain, Catherine; Joehl, Norbert (2006). Design and Optimization of Passive UHF RFID Systems. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 0387447105.

- ^ Belohlavek, Peter; Wagner, John W (2008). Innovation: The Lessons of Nikola Tesla. Blue Eagle Group. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9876510096.

- ^ "Dennis Papadopoulos interview". Tesla: Master of Lightning - companion site for 2000 PBS television documentary. PBS.org, US Public Broadcasting Service website. 2000. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Legal statement by Tesla to attorney Drury W. Cooper, from 1916 internal document of the law firm Kerr, Page & Cooper, New York City, cited in Anderson, Leland (1992). Nikola Tesla on His Work with Alternating Currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power: An Extended Interview. Sun Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 1893817016.

Further reading

- "Boundless Space: A Bus Bar", The Electrical World, Vol 32, No. 19, November 5, 1898.

- Tesla, Nikola, THE PROBLEM OF INCREASING HUMAN ENERGY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE HARNESSING OP THE SUN'S ENERGY, Century Magazine, June 1900

- Tesla, Nikola, "The Transmission of Electrical Energy Without Wires", Electrical World and Engineer, Jamuary 7, 1905.

- Massie, Walter Wentworth, Wireless telegraphy and telephony popularly explained. New York, Van Nostrand. 1908 ("WITH SPECIAL ARTICLE BY NIKOLA TESLA")

- Tesla, Nikola, "The True Wireless", Electrical Experimenter, 1919

- Tesla, Nikola, "World System of Wireless Transmission of Energy", Telegraph and Telegraph Age, October 16, 1927.

- Electric Spacecraft – A Journal of Interactive Research by Leland Anderson, "Rare Notes from Tesla on Wardenclyffe" in Issue 26, September 14, 1998. Contains drawings and selected typescripts of Tesla's notes from 1901, archived at the Nikola Tesla Museum in Belgrade.

External links

- PBS Tesla Master of Lightning Tower of Dreams, global wireless telecommunications

- Wardenclyffe Tower at Structurae