Derby Silk Mill

It has been suggested that Lombe's Mill be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since February 2017. |

The museum and the River Derwent | |

| Established | 1974 |

|---|---|

| Location | Derby, England |

| Coordinates | 52°55′33″N 1°28′33″W / 52.925833°N 1.475833°W |

| Type | Industrial museum |

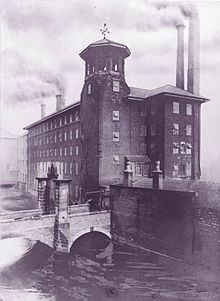

Derby Silk Mill, formerly known as Derby Industrial Museum, is a museum of industry and history in Derby, England. The museum is housed in Lombe's Mill, a historic former silk mill which marks the southern end of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site.

History

Between 1717 and 1721 George Sorocold built Britain’s first mill for the Lombe brothers, beside the River Derwent to house machines for "doubling" or twisting silk into thread.

John Lombe's idea of mill was inspired by contemporary smaller and less effective mills he studied during the period in which he worked in Italy: traditionally the spinning wheel was used for producing small quantities of silk thread at the homes of local spinsters, the new machines were capable of producing far greater quantities of silk and provided serious competition for the Italians. The machines required large buildings and a power source. An undershot water wheel turned by the mill fleam on the west side of the new mill drove the spinning machines.

John Lombe died in 1722 in mysterious circumstances, believed to have been poisoned by an Italian assassin paid by his Italian commercial opponents. His half brother, Sir Thomas Lombe, died on 2 June 1739 leaving his estate to his widow and their two daughters.

Dame Elizabeth advertised the lease for sale in 1739, and the remaining 64 years of the lease were assigned to Richard Wilson junior of Leeds for £2,800. Wilson remained in Leeds leaving the running of the mill to his partners, William and Samuel Lloyd, both London merchants, with Thomas Bennet as manager, taking a proportion of the profits.

A description of the mill by William Wilson dating from some time between 1739 and 1753 has survived:

The original "Italian" works of five storeys high housed 26 Italian winding engines that spun the raw silk on each of the upper three floors whilst the lower two storeys contained eight spinning mills producing basic thread and four twist mills.

These circular spinning machines (also known as 'throwing machines'), were the most significant innovation of the factory. Together with the single source of power (water), and the large size and organisation of the workforce for the period (200-400, according to contemporary sources), the total process of production from raw silk to fine quality thread has led the Lombes' silk mill to be described as the first successful use of the factory system in Britain.[1]

The Silk Mill was a tourist attraction in Derby and was visited by Boswell in September 1777. Not all the visitors were impressed by conditions. Torrington commented on the "heat, stinks and noise", whilst Fairholt in 1835 was appalled by the sickly appearance of the poor children. Foreign visitors also included the mill in their itinerary.

William Hutton was an employee and he later recalled the long hours, low wages and beatings. Work only stopped in time of drought, extreme frost or problems with the silk supply, although unofficial holidays were taken during elections and Derby races in August 1748.

The partnership of Wilson and Lloyd ended in 1753 after acrimony and legal suits. Lloyd remained in possession of the building and machinery. In 1765 Thomas Bennet bought the premises from Lloyd subject to a mortgage to the Wilson family but neglected the building during years of trade recession and competition from other mills in Derby and Cheshire. Lamech Swift became the sub-tenant in 1780 paying an annual rent of £7 to the corporation and £170 to Thomas Wilson, brother of Richard and William. Despite a row with the corporation over repairs to the weirs in 1781, he remained in occupation until the lease expired in 1803 when the corporation advertised a lease to run for 60 years. The advertisement reveals that the "Italian works" was still used for throwing silk.

November 1833 saw the beginning of industrial unrest in Derby which led to the formation of the Grand National Trades Union in February 1834. It predated the Tolpuddle Martyrs by several months. Taylor’s Silk Mill was not at the centre of the controversy although he was one of the employers who agreed not to employ any worker who was a union member. By the middle of April 1834 Taylor reported that two-thirds of his machinery was working and many of his former workers were applying for reinstatement. According to "The Derby Mercury" some of the former unionists were never able to find fresh employment in Derby. This event is commemorated by a march organised by the Derby Trades Union Council[2] annually on the weekend before MayDay.[3] The story of the Derby Lock-out was dramatised as a short film sponsored by Unite the union in 2015. This was first screened at Derby Quad cinema on 25 April 2015 [4]

The Taylor family remained in occupation of the mill until 1865 when bankruptcy forced them to sell the machinery and lease. "The Derby Mercury" advertised several silk mills for sale that year when a general slump hit the industry. This took place four years before the Cobden Treaty with France which is said to have effectively destroyed the British silk industry.

The connection with silk production ended in about 1908 when F.W. Hampshire and Company, the chemists, moved into the premises to make fly papers and cough medicines. On 5 December 1910 at 5.00 am, fire broke out in the adjacent Sowter Brothers flour mill and engulfed the Silk Mill. The mill's east wall fell into the river and the building was gutted. Great efforts were made by the borough fire brigade and the Midland Railway Company who saved the shell of the tower and the outline of the doorways leading into the original five floors. These can be seen today on the tower staircase. The building was rebuilt to the same height but with three storeys instead of five and remains that way today.

During the 1920s, ownership passed to the Electricity Authority. It was used as stores, workshops and a canteen. Hidden from the road by the power station, its existence was forgotten by the public until the power station was demolished in 1970. It was then adapted for use as Derby’s Industrial Museum, which opened on 29 November 1974.

Closure and mothballing

Derby City Council temporarily closed the museum on 3 April 2011[5] to free funds for the redevelopment of the Silk Mill museum and other museums in the city.[citation needed] The Report of the Strategic Director of Neighbourhoods (Item 7 put before the Council Cabinet meeting held on 26 October 2010) indicated that this would result in the loss of 8.6 full-time jobs but would release £197,000 a year to mitigate the loss of "Renaissance Programme" funding. No date for re-opening was given in the report,[6] although a period of two years was reported.[7]

The Silk Mill Redevelopment Project has now started, with an expected completion date of 2019/2020.[8] Until the project is complete the majority of the museum is closed, with limited opening hours.[9]

Reopening

In October 2013 a programme started to reinvent the museum for the 21st century incorporating the principles of Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics (STEAM). The museum is now open 2 days a week.[10]

Sources

- ^ Lombe's Mill: An Exercise in Reconstruction, Industrial Archaeology Review, Anthony Calladine (1993)

- ^ "Derby Trades Union Council Website".

- ^ Whitehead, Bill (April 1999). "The Derby Lock-Out of 1833-34 and the Origins of the Labour Movement". Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Silk Mill". Derby City Council. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Report of the Strategic Director of Neighbourhoods". Derby City Council. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ J Royston (25 February 2011). "Don't allow this valuable museum to be sacrificed". This Is Derbyshire. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Derby Silk Mill Participative Design Workshop". Derby Museums. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Derby Silk Mill Participative Design Workshop". Derby Museums. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Derby Museums - The Silk Mill". Derby Museums / Derby City Council.

Sources of information:

- Derby Industrial Museum, Derby Evening Telegraph and Derby Library Service. (1999)

* The Derby Lock-Out and the origins of the labour movement Bill Whitehead (2001)

* Struck out! Derby in Crisis: the Silk Mill Lock-Out 1833-4, Derby, H. E. Butterton (1997)

External links

- Articles to be merged from February 2017

- Industrial buildings completed in 1721

- Grade II listed buildings in Derby

- Textile mills in England

- Industry museums in England

- Textile museums in the United Kingdom

- Museums established in 1974

- Museums in Derby

- Watermills in Derbyshire

- Collections of Derby Museum and Art Gallery

- 1974 establishments in England

- Silk mills

- 1721 establishments in England

- Grade II listed industrial buildings