Vrishni heroes

The Vrishni heroes (IAST: Vṛṣṇi Viras),[6] also referred to as Pancha-viras (IAST: Pañcavīras),[6] are a group of five legendary heroes in Vaishnava tradition of Hinduism.[6][7][8] Their earliest worship is attestable in the clan of the Vrishnis near Mathura by about 3rd-century BCE.[1][6][9] Their ancient worship has been variously proposed as either a cross-sectarian (Jainism–Hinduism) tradition or the Bhagavata tradition (Hinduism).[10]

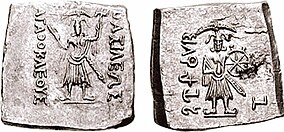

The Vrishnis were already known in the late Vedic literature. They are also mentioned by Pāṇini in Astadhyayi verse 6.2.34, while Krishna is referred to as Krishna Varshneya in verse 3.187.51 of the Mahabharata.[11] Beyond texts, their importance in ancient India is attested by the ancient inscriptions found near Mathura and coins discovered near Ai-Khanoum (Afghanistan) with Vrishni heroes images and Brahmi script text.[6]

In Vaishnavism, the Vrishni heroes are generally identified as Samkarshana (Balarama-Samkarshana, son of Vasudeva by Rohini),[1][11] Vāsudeva (Vāsudeva-Krishna, son of Vasudeva by Devaki),[1][11] Pradyumna (son of Vasudeva by Rukmini),[1] Samba (son of Vasudeva by Jambavati),[1] and Aniruddha (son of Pradyumna).[12] Epigraphical evidence suggests that their legends and worship – sometimes referred to as the Bhagavata movement – swiftly expanded to other parts of India by the start of the common era.[9][12][13]

Identity

The historical roots and the identity of the Vrishni heroes is unclear. Many competing theories have been proposed. According to Rosenfield, the five heroes of the Vrishnis may have been ancient historical rulers in the region of Mathura, and Vasudeva and Krishna "may well have been kings of this dynasty as well".[14] Banerjee considered that they may have been semi-deified legendary kings who came to be considered as Vishnu's avatars.[14] This would correspond to an early form of Vaishnavism, currently described as the Pancaratra system.[14] According to Christopher Austin, they are characters linked to the end of Mahabharata, reflecting the three generations of Vrishnis of Krishna from the Bhagavad Gita fame, his son, his grandson along with the Balarama (Samkarshana). This view is supported by Srinivasan and Banerjea based on evidence in two Puranic passages and the Mora well inscription.[9] In early Hinduism, the five Vrishni heroes have been identified as Vāsudeva-Krishna, Samkarsana-Balarama, Pradyumna, Aniruddha and Samba as known from the Medieval Vayu Purana.[4][2]

Another theory has been proposed by Heinrich Luders. Based on analysis of 10th to 12th century Jaina texts, Luders proposed that Vrishnis may have roots in Jainism, noting the co-existence of the Jain and Vrishni-related archaeological findings in Mathura. He names the Vrishni heroes as Baladeva, Akrura, Anadhrsti, Sarana and Viduratha – all Jain heroes and with Akrura as the commander.[10] In fact, the cult of the Vrishnis may have been cross-sectarian, much like the cult of the Yakshas.[10]

Mora Vrishni heroes

The Vrishni heroes are mentionned in the Mora Well Inscription in Mathura, dated to the time of the Northern Satraps Sodasa, in which they are called Bhagavatam.[15][16][17] Statue fragments were found in Mora, which are thought to represent some of the Vrishni heroes.[2][14] Two uninscribed male torsos were discovered in the mound, both of high craftsmanship and in Indian style and costume.[14] They are similar with minor variations, suggesting they may have been part of a series.[18] They share some sculptural characteristics with the Yaksha statues found in Mathura, such as the sculpting in the round, or the clothing style.[2] Sonya Rhie Quintanilla also supports an attribution of the torso to the five Vrishnis, and dates them to around the time of Sodasa (circa 15 CE), which is confirmed on artistic grounds.[4]

Hindu Vrishni clan

The famous "Caturvyūha Viṣṇu" statue in Mathura Museum is an attempt to show in one composition Vishnu (Vasudeva) together with the other members of the Vrishni clan of the Pancharatra system: Samkarsana, Pradyumna and Aniruddha, with Samba missing, Vishnu being the central deity from whom the others emanate.[5] The back of the relief is carved with the branches of a Kadamba tree, symbolically showing the relationship being the different deities.[5]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 436-438. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ a b c d "We have actually discovered in the excavations at the Mora shrine stone torsos representing the Vrishni Heroes (...) Their style closely follows that of the free-standing Yakshas in that they are carved in the round. They are dressed in a dhoti and uttaraya and some types of ornaments as found on the Yaksha figures, their right hand is held in ahbayamudra..." in "Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharana (1965). Indian Art: A history of Indian art from the earliest times up to the third century A.D. Prithivi Prakashan. p. 253.

- ^ This statue appears in Fig.51 as one of the statues excavated in the Mora mound, in Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press. p. 151-152 and Fig.51.

- ^ a b c Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4.

- ^ a b c Paul, Pran Gopal; Paul, Debjani (1989). "Brahmanical Imagery in the Kuṣāṇa Art of Mathurā: Tradition and Innovations". East and West. 39 (1/4): 132–136, for the photograph p.138. ISSN 0012-8376.

- ^ a b c d e Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL Academic. pp. 211–220. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- ^ Lavanya Vemsani (2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names. ABC-CLIO. pp. 23–25, 239. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.;

For their regional significance in contemporary Hinduism, see: [a] Couture, André; Schmid, Charlotte; Couture, Andre (2001). "The Harivaṃśa, the Goddess Ekānaṃśā, and the Iconography of the Vṛṣṇi Triads". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 121 (2): 173–192. doi:10.2307/606559.; [b] Doris Srinivasan (1979). "Early Vaiṣṇava Imagery: Caturvyūha and Variant Forms". Archives of Asian Art. 32: 39–54. JSTOR 20111096. - ^ R Champakalakshmi (1990). H. V. Sreenivasa Murthy (ed.). Essays on Indian History and Culture. Mittal Publications. pp. 52–60. ISBN 978-81-7099-211-0.

- ^ a b c Christopher Austin (2018). Diana Dimitrova and Tatiana Oranskaia (ed.). Divinizing in South Asian Traditions. Taylor & Francis. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-1-351-12360-0.

- ^ a b c Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4.

- ^ a b c Joanna Gottfried Williams (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. pp. 127–131. ISBN 90-04-06498-2.

- ^ a b Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 436–440. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL. p. 129. ISBN 978-90-04-06498-0.

- ^ a b c d e Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press. p. 151-152 and Fig.51.

- ^ Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL Academic. pp. 211–214, 308-311 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- ^ Sonya Rhie Quintanilla (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL Academic. p. 260. ISBN 90-04-15537-6.

- ^ Lavanya Vemsani (2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.

- ^ Lüders, H. (1937). Epigraphia Indica Vol.24. pp. 199–200.