Anglerfish

{{Automatic taxobox | name = Anglerfish

| fossil_range =

Early Cretaceous – recent

| image = Humpback anglerfish.png

| image_caption = Humpback anglerfish, Melanocetus johnsonii

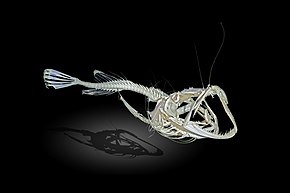

| taxon = Lophiiformes the yeetfish are dangerous boys so be careful Centrophryne spinulosa, 136 mm SL

(B) Cryptopsaras couesii, 34.5 mm SL

(C) Himantolophus appelii, 124 mm SL

(D) Diceratias trilobus, 86 mm SL

(E) Bufoceratias wedli, 96 mm SL

(F) Bufoceratias shaoi, 101 mm SL

(G) Melanocetus eustalus, 93 mm SL

(H) Lasiognathus amphirhamphus, 157 mm SL

(I) Thaumatichthys binghami, 83 mm SL

(J) Chaenophryne quasiramifera, 157 mm SL.]]

The anglerfish is a fish of the teleost order Lophiiformes (/ˌlɒfiɪˈfɔːrmiːz/).[1] It is a bony fish named for its characteristic mode of predation, in which a fleshy growth from the fish's head (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure for other fish.

Some anglerfish are notable for extreme sexual dimorphism and sexual symbiosis of the small male with the much larger female, seen in the suborder Ceratioidei. In these species, males may be several orders of magnitude smaller than females.[2]

Anglerfish occur worldwide. Some are pelagic (dwelling away from the sea floor), while others are benthic (dwelling close to the sea floor). Some live in the deep sea (e.g., Ceratiidae), while others on the continental shelf (e.g., the frogfishes Antennariidae and the monkfish/goosefish Lophiidae). Pelagic forms are most laterally compressed, whereas the benthic forms are often extremely dorsoventrally compressed (depressed), often with large upward-pointing mouths.

Evolution

A mitochondrial genome phylogenetic study suggested the anglerfishes diversified in a short period of the early to mid-Cretaceous, between 130 and 100 million years ago.[3]

Classification

FishBase,[1] Nelson, [4] and Pietsch[5] list 18 families, but ITIS[6] lists only 16. The following taxa have been arranged to show their evolutionary relationships.[2]

- Suborder Lophoiodei

- Lophiidae (goosefishes or monkfishes)

- Suborder Antennarioidei

- Antennariidae (frogfishes)

- Tetrabrachiidae (four-armed frogfishes)[7]

- Brachionichthyidae (handfishes)

- Lophichthyidae (Boschma's frogfish)[7]

- Suborder Chaunacoidei

- Chaunacidae (sea toads)

- Suborder Ogcocephaloidei

- Ogcocephalidae (batfishes)

- Suborder Ceratioidei

- Centrophrynidae (prickly seadevils)

- Ceratiidae (warty seadevils)

- Himantolophidae (footballfishes)

- Diceratiidae (doublespine seadevils)

- Melanocetidae (black seadevils)

- Thaumatichthyidae (wolf-trap seadevils)

- Oneirodidae (dreamers)

- Caulophrynidae (fanfin seadevils)

- Neoceratiidae (needlebeard seadevil)

- Gigantactinidae (whipnose seadevils)

- Linophrynidae (leftvent seadevils)

Anatomy

All anglerfish are carnivorous and are thus adapted for the capture of prey. Ranging in color from dark gray to dark brown, deep-sea species have large heads that bear enormous, crescent-shaped mouths full of long, fang-like teeth angled inward for efficient prey grabbing. Their length can vary from 2–18 cm (1–7 in), with a few types getting as large as 100 cm (39 in).[8] , but this variation is largely due to sexual dimorphism with females being much larger than males.[9] Frogfish and other shallow-water anglerfish species are ambush predators, and often appear camouflaged as rocks, sponges or seaweed. [10]

Most adult female ceratioid anglerfish have a luminescent organ called the esca at the tip of a modified dorsal ray (the illicium or fishing rod). The organ has been hypothesized to serve the obvious purpose of luring prey in dark, deep-sea environments, but also serves to call males' attention to the females to facilitate mating.

The source of luminescence is symbiotic bacteria that dwell in and around the esca, enclosed in a cup-shaped reflector containing crystals, probably consisting of guanine. In some species, the bacteria recruited to the esca are incapable of luminescence independent of the anglerfish, suggesting they have developed a symbiotic relationship and the bacteria are unable to synthesize all of the chemicals necessary for luminescence on their own. They depend on the fish to make up the difference. Electron microscopy of these bacteria in some species reveals they are Gram-negative rods that lack capsules, spores, or flagella. They have double-layered cell walls and mesosomes. A pore connects the esca with the seawater, which enables the removal of dead bacteria and cellular waste, and allows the pH and tonicity of the culture medium to remain constant. This, as well as the constant temperature of the bathypelagic zone inhabited by these fish, is crucial for the long-term viability of bacterial cultures.[11][12]

The light gland is always open to the exterior, so it is possible that the fish acquires the bacteria from the seawater. However, it appears that each species uses its own particular species of bacteria, and these bacteria have never been found in seawater. Haygood (1993) theorized that esca discharge bacteria during spawning and the bacteria are thereby transferred to the eggs.[12]

In most species, a wide mouth extends all around the anterior circumference of the head, and bands of inwardly inclined teeth line both jaws. The teeth can be depressed so as to offer no impediment to an object gliding towards the stomach, but prevent its escape from the mouth.[13] The anglerfish is able to distend both its jaw and its stomach, since its bones are thin and flexible, to enormous size, allowing it to swallow prey up to twice as large as its entire body.[14]

Behaviour

Swimming and energy conservation

In 2005, near Monterey, California, at 1474 metres depth, an ROV filmed a female ceratioid anglerfish of the genus Oneirodes for 24 minutes. When approached, the fish retreated rapidly, but in 74% of the video footage, it drifted passively, oriented at any angle. When advancing, it swam intermittently at a speed of 0.24 body lengths per second, beating its pectoral fins in-phase. The lethargic behaviour of this ambush predator is suited to the energy-poor environment of the deep sea.[15]

Another in situ observation of three different whipnose anglerfish showed unusual inverted swimming behavior. Fish were observed floating inverted completely motionless with the illicium hanging down stiffly in a slight arch in front of the fish. The illicium was hanging over small visible burrows. It was suggested this is an effort to entice prey and an example of low-energy opportunistic foraging and predation. When the ROV approached the fish, they exhibited burst swimming, still inverted.[16]

The jaw and stomach of the anglerfish can extend to allow it to consume prey up to twice its size. Because of the small amount of food available in the anglerfish's environment this adaptation allows the anglerfish to store food when there is an abundance.[17]

Predation

The name "anglerfish" derives from the species' characteristic method of predation. Anglerfish typically have at least one long filament sprouting from the middle of their heads, termed the illicium. The illicium is the detached and modified first three spines of the anterior dorsal fin. In most anglerfish species, the longest filament is the first. This first spine protrudes above the fish's eyes and terminates in an irregular growth of flesh (the esca), and can move in all directions. Anglerfish can wiggle the esca to make it resemble a prey animal, which lures the anglerfish's prey close enough for the anglerfish to devour them whole.[18] Some deep-sea anglerfish of the bathypelagic zone also emit light from their esca to attract prey.[19]

Because anglerfish are opportunistic foragers, they show a range of preferred prey with fish at the extremes of the size spectrum, whilst showing increased selectivity for certain prey. One study examining the stomach contents of threadfin anglerfish off the Pacific coast of Central America found these fish primarily ate two categories of benthic prey: crustaceans and teleost fish. The most frequent prey were pandalid shrimp. 52% of the stomachs examined were empty, supporting the observations that anglerfish are low energy consumers.[20]

Reproduction

Some anglerfish, like those of the Ceratiidae, or sea devils employ an unusual mating method.[21] Because individuals are locally rare, encounters are also very rare. Therefore, finding a mate is problematic. When scientists first started capturing ceratioid anglerfish, they noticed that all of the specimens were female. These individuals were a few centimetres in size and almost all of them had what appeared to be parasites attached to them. It turned out that these "parasites" were highly reduced male ceratioids. This indicates some taxa of anglerfish use a polyandrous mating system.

Certain ceratioids rely on parabiotic reproduction. Free-living males and unparasitized females in these species never have fully developed gonads. Thus, males never mature without attaching to a female, and die if they cannot find one.[2] At birth, male ceratioids are already equipped with extremely well-developed olfactory organs[22] that detect scents in the water. Males of some species also develop large, highly specialized eyes that may aid in identifying mates in dark environments. The male ceratioid lives solely to find and mate with a female. They are significantly smaller than a female anglerfish, and may have trouble finding food in the deep sea. Furthermore, growth of the alimentary canals of some males becomes stunted, preventing them from feeding. Some taxa have jaws that are never suitable or effective for prey capture.[22] These features mean the male must quickly find a female anglerfish to prevent death. The sensitive olfactory organs help the male to detect the pheromones that signal the proximity of a female anglerfish.

The methods anglerfish use to locate mates vary. Some species have minute eyes that are unfit for identifying females, while others have underdeveloped nostrils, making them unlikely to effectively find females by scent.[2] When a male finds a female, he bites into her skin, and releases an enzyme that digests the skin of his mouth and her body, fusing the pair down to the blood-vessel level.[22] The male becomes dependent on the female host for survival by receiving nutrients via their shared circulatory system, and provides sperm to the female in return. After fusing, males increase in volume and become much larger relative to free-living males of the species. They live and remain reproductively functional as long as the female lives, and can take part in multiple spawnings.[2] This extreme sexual dimorphism ensures that when the female is ready to spawn, she has a mate immediately available.[23] Multiple males can be incorporated into a single individual female with up to eight males in some species, though some taxa appear to have a "one male per female" rule.[2]

Symbiosis is not the only method of reproduction in anglerfish. In fact, many families, including the Melanocetidae, Himantolophidae, Diceratiidae, and Gigantactinidae, show no evidence of male symbiosis.[24] Females in some of these species contain large, developed ovaries and free-living males have large testes, suggesting these sexually mature individuals may spawn during a temporary sexual attachment that does not involve fusion of tissue. Males in these species also have well-toothed jaws that are far more effective in hunting than those seen in symbiotic species.[24]

Sexual symbiosis may be an optional strategy in some species of anglerfishes.[2] In the Oneirodidae, females carrying symbiotic males have been reported in Leptacanthichthys and Bertella—and others that were not still developed fully functional gonads.[2] One theory suggests the males attach to females regardless of their own reproductive development if the female is not sexually mature, but when both male and female are mature, they spawn then separate.[2]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

One explanation for the evolution of sexual symbiosis is that the relatively low density of females in deep-sea environments leaves little opportunity for mate choice among anglerfish. Females remain large to accommodate fecundity, as is evidenced by their large ovaries and eggs. Males would be expected to shrink to reduce metabolic costs in resource-poor environments and would develop highly specialized female-finding abilities. If a male manages to find a female, then symbiotic attachment is ultimately more likely to improve lifetime fitness relative to free living, particularly when the prospect of finding future mates is poor. An additional advantage to symbiosis is that the male’s sperm can be used in multiple fertilizations, as he always remains available to the female for mating. Higher densities of male-female encounters might correlate with species that demonstrate facultative symbiosis or simply use a more traditional temporary contact mating.[25]

The spawn of the anglerfish of the genus Lophius consists of a thin sheet of transparent gelatinous material 25 cm (10 in) wide and greater than 10 m (33 ft) long.[26] The eggs in this sheet are in a single layer, each in its own cavity. The spawn is free in the sea. The larvae are free-swimming and have the pelvic fins elongated into filaments.[13] Such an egg sheet is rare among fish.

Threats

Northwest European Lophius species are listed by the ICES as "outside safe biological limits".[27] Additionally, anglerfish are known to occasionally rise to the surface during El Niño, leaving large groups of dead anglerfish floating on the surface.[27]

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the American angler (Lophius americanus), the angler (Lophius piscatorius), and the black-bellied angler (Lophius budegassa) to its seafood red list—a list of fish commonly sold worldwide with a high likelihood of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries.[28]

Human consumption

One family, the Lophiidae, is of commercial interest with fisheries found in western Europe, eastern North America, Africa, and East Asia. In Europe and North America, the tail meat of fish of the genus Lophius, known as monkfish or goosefish (North America), is widely used in cooking, and is often compared to lobster tail in taste and texture.

In Asia, especially Korea and Japan, monkfish liver, known as ankimo, is considered a delicacy.[29] Anglerfish is especially heavily consumed in South Korea, where it is featured as the main ingredient in dishes such as Agujjim.

Timeline of genera

Anglerfish appear in the fossil record as follows:[30]

References

- ^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Order Lophiiformes". FishBase. February 2006 version.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pietsch, Theodore W. (25 August 2005). "Dimorphism, parasitism, and sex revisited: modes of reproduction among deep-sea ceratioid anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes)". Ichthyological Research. 52 (3): 207–236. doi:10.1007/s10228-005-0286-2.

- ^ Miya, M.; T. Pietsch; J. Orr; R. Arnold; T. Satoh; A. Shedlock; H. Ho; M. Shimazaki; M. Yabe (2010). "Evolutionary history of anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes): a mitogenomic perspective". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 58. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-58. PMC 2836326. PMID 20178642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Joseph S. Nelson (29 April 1994). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-54713-6.

- ^ Theodore W. Pietsch (2009) (2009). Oceanic Anglerfishes: Extraordinary Diversity in the Deep Sea. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25542-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Lophiiformes". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 3 April 2006.

- ^ a b Boschma's frogfish and the four-armed frogfish are included in the Antennariidae in ITIS.

- ^ "Anglerfish". National Geographic. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "Fish Identification". fishbase.org. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "Camouflage". Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ O'Day, William T. (1974). Bacterial Luminescence in the Deep-Sea Anglerfish (PDF). LA: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

- ^ a b Munk, Ole; Hansen, Kjeld; Herring, Peter J. (2009). "On the Development and Structure of the Escal Light Organ of Some Melanocetid Deep Sea Anglerfishes (Pisces: Ceratioidei)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 78 (4): 1321. doi:10.1017/S0025315400044520. ISSN 0025-3154.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Angler". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 15.

- ^ "Anglerfish". National Geographic. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Luck, Daniel Garcia; Pietsch, Theodore W. (4 June 2008). "Observations of a Deep-sea Ceratioid Anglerfish of the Genus Oneirodes (Lophiiformes: Oneirodidae)". Copeia. 2008 (2): 446–451. doi:10.1643/CE-07-075.

- ^ Moore, Jon A. (31 December 2001). "Upside-Down Swimming Behavior in a Whipnose Anglerfish (Teleostei: Ceratioidei: Gigantactinidae)". Copeia. 4. 2002 (4): 1144–1146. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2002)002[1144:udsbia]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 1448539.

- ^ http://www.seasky.org/deep-sea/anglerfish.html

- ^ Smith, William John (2009). The Behavior of Communicating: an ethological approach. Harvard University Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-674-04379-4.

Others rely on the technique adopted by a wolf in sheep's clothing—they mimic a harmless species. ... Other predators even mimic their prey's prey: angler fish (Lophiiformes) and alligator snapping turtles Macroclemys temmincki can wriggle fleshy outgrowths of their fins or tongues and attract small predatory fish close to their mouths.

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ^ Espinoza, Mario; Ingo Wehrtmann (2008). "Stomach content analyses of the threadfin anglerfish Lophiodes spilurus (Lophiiformes: Lophiidae) associated with deepwater shrimp fisheries from the central Pacific of Costa Rica". Revista de Biología Tropical. 4. 56 (4). doi:10.15517/rbt.v56i4.5772. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Gorey, Colm (23 March 2018). "Scientists stunned to capture first mating footage of bizarre anglerfish". SiliconRepublic.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Gould, Stephen Jay (1983). Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-393-01716-8.

ceratioid males develop gigantic nostrils...relative to body size, some ceratioids have larger nasal organs than any other vertebrate

- ^ Theodore W. Pietsch (1975). "Precocious sexual parasitism in the deep sea ceratioid anglerfish, Cryptopsaras couesi Gill". Nature. 256 (5512): 38–40. doi:10.1038/256038a0.

- ^ a b Pietsch, Theodore W. (8 March 1972). "A Review of the Monotypic Deep-Sea Anglerfish Family Centrophrynidae: Taxonomy, Distribution and Osteology". Copeia. 1972 (1): 17–47. doi:10.2307/1442779. JSTOR 1442779.

- ^ Miya, Masaki; Pietsch, Theodore W; Orr, James W; Arnold, Rachel J; Satoh, Takashi P; Shedlock, Andrew M; Ho, Hsuan-Ching; Shimazaki, Mitsuomi; Yabe, Mamoru; Nishida, Mutsumi (1 January 2010). "Evolutionary history of anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes): a mitogenomic perspective". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 58. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-58. PMC 2836326. PMID 20178642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Prince, E. E. 1891. Notes on the development of the angler-fish (Lophius piscatorius). Ninth Annual Report of the Fishery Board for Scotland (1890), Part III: 343–348.

- ^ a b Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-189780-2.

- ^ Greenpeace International Seafood Red list Archived 20 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Goosefish". All the Sea. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

Further reading

- Anderson, M. Eric, and Leslie, Robin W. 2001. Review of the deep-sea anglerfishes (Lophiiformes: Ceratioidei) of southern Africa. Ichthyological Bulletin of the J.L.B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology; No. 70. J.L.B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology, Rhodes University