Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes (Ἐρατοσθένης) | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Eratosthenes | |

| Born | 276 BC |

| Died | 194 BC |

| Occupation(s) | Scholar, librarian, poet and inventor |

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (Ancient Greek: Ἐρατοσθένης, IPA: [eratostʰénɛːs]; English: /ɛrəˈtɒsθəniːz/; c. 276 BC[1] – c. 195 BC[2]) was a Greek mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist.

He was the first person to use the word "geography" in Greek and he invented the discipline of geography as we understand it.[3] He invented a system of latitude and longitude.

He was the first person to calculate the circumference of the earth by using a measuring system using stades, or the length of stadiums during that time period (with remarkable accuracy). He was the first to calculate the tilt of the Earth's axis (also with remarkable accuracy). He may also have accurately calculated the distance from the earth to the sun and invented the leap day.[4] He also created the first map of the world incorporating parallels and meridians within his cartographic depictions based on the available geographical knowledge of the era. In addition, Eratosthenes was the founder of scientific chronology; he endeavoured to fix the dates of the chief literary and political events from the conquest of Troy.

According to an entry[5] in the Suda (a 10th century reference), his contemporaries nicknamed him beta, from the second letter of the Greek alphabet, because he supposedly proved himself to be the second best in the world in almost every field.[6]

Life

Eratosthenes was born in Cyrene (in modern-day Libya). He was the third chief librarian of the Great Library of Alexandria, the center of science and learning in the ancient world, and died in Alexandria, then the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Eratosthenes studied in Alexandria, and claimed to have also studied for some years in Athens. In 236 BC, he was appointed by Ptolemy III Euergetes as librarian of the Alexandrian library, succeeding the second librarian, Apollonius of Rhodes.[7] He made several important contributions to mathematics and science, and was a good friend to Archimedes. Around 255 BC, he invented the armillary sphere. In On the Circular Motions of the Celestial Bodies, Cleomedes credited him with having calculated the Earth's circumference around 240 BC, using knowledge of the angle of elevation of the sun at noon on the summer solstice in Alexandria and on Elephantine Island near Syene (now Aswan, Egypt).

Eratosthenes believed there was good and bad in every nation and criticized Aristotle for arguing that humanity was divided into Greeks and barbarians, and that the Greeks should keep themselves racially pure.[8] By 195 BC, Eratosthenes became blind. He died in 194 BC at the age of 82.

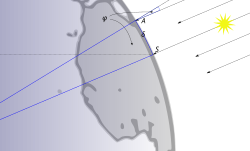

Eratosthenes' measurement of the Earth's circumference

Eratosthenes calculated the circumference of the Earth without leaving Egypt. Eratosthenes knew that, on the summer solstice, at local noon in the Ancient Egyptian city of Swenet (known in Greek as Syene, and in the modern day as Aswan) on the Tropic of Cancer, the sun would appear at the zenith, directly overhead (he had been told that the shadow of someone looking down a deep well would block the reflection of the Sun at noon). Using a gnomon, which is a vertical rod or stylus that casts a shadow on a horizontal surface, he measured the sun's angle of elevation at noon on the solstice in his hometown of Alexandria, and found it to be 1/50th of a circle (7°12') south of the zenith. He could have used a compass to measure the angle of the shadow casted.[9] Assuming that the Earth was spherical (360°), and that Alexandria was due north of Syene, he concluded that the meridian arc distance from Alexandria to Syene must therefore be 1/50 = 7°12'/360°, and was therefore 1/50 of the total circumference of the Earth. His knowledge of the size of Egypt after many generations of surveying trips for the Pharaonic bookkeepers gave a distance between the cities of 5,000 stadia (about 500 geographical miles or 927.7 km). This distance was corroborated by inquiring about the time that it takes to travel from Syene to Alexandria by camel. He rounded the result to a final value of 700 stadia per degree, which implies a circumference of 252,000 stadia. The exact size of the stadion he used is frequently debated. The common Attic stadion was about 185 m,[10] which would imply a circumference of 46,620 km, which is off the actual circumference by 16.3%; too large an error to be considered as 'accurate'. However, if we assume that Eratosthenes used the "Egyptian stadion"[11] of about 157.5 m, his measurement turns out to be 39,690 km, an error of less than 2%.[12]

Other astronomical distances

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

Eusebius of Caesarea in his Preparatio Evangelica includes a brief chapter of three sentences on celestial distances (Book XV, Chapter 53). He states simply that Eratosthenes found the distance to the sun to be "σταδίων μυριάδας τετρακοσίας καὶ ὀκτωκισμυρίας" (literally "of stadia myriads 400 and 80,000") and the distance to the moon to be 780,000 stadia. The expression for the distance to the sun has been translated either as 4,080,000 stadia (1903 translation by E. H. Gifford), or as 804,000,000 stadia (edition of Edouard des Places, dated 1974–1991). The meaning depends on whether Eusebius meant 400 myriad plus 80,000 or "400 and 80,000" myriad. With a stadium of 185 meters, 804,000,000 stadia is 149,000,000 kilometers, approximately the distance from the earth to the sun.

Prime numbers

Eratosthenes also proposed a simple algorithm for finding prime numbers. This algorithm is known in mathematics as the Sieve of Eratosthenes.

In mathematics, the sieve of Eratosthenes (Greek: κόσκινον Ἐρατοσθένους), one of a number of prime number sieves, is a simple, ancient algorithm for finding all prime numbers up to any given limit. It does so by iteratively marking as composite (i.e. not prime) the multiples of each prime, starting with the multiples of 2. The multiples of a given prime are generated starting from that prime, as a sequence of numbers with the same difference, equal to that prime, between consecutive numbers. This is the sieve's key distinction from using trial division to sequentially test each candidate number for divisibility by each prime.

Works

- Περὶ τῆς ἀναμετρήσεως τῆς γῆς (On the Measurement of the Earth)[13] (lost, summarized by Cleomedes)

- Geographica (lost, criticized by Strabo)

- Arsinoe (a memoir of queen Arsinoe; lost; quoted by Athenaeus in the Deipnosophistae)

- A fragmentary collection of Hellenistic myths about the constellations, called Catasterismi (Katasterismoi), was attributed to Eratosthenes, perhaps to add to its credibility.

Things named after Eratosthenes

- Eratosthenes (crater) on the moon

- Eratosthenian period in the lunar geologic timescale

- Eratosthenes Seamount in the eastern Mediterranean Sea

See also

Notes

- ^ The Suda states that he was born in the 126th Olympiad, (276–272 BC). Strabo (Geography, i.2.2), though, states that he was a "pupil" (γνωριμος) of Zeno of Citium (who died 262 BC), which would imply an earlier year-of-birth (c. 285 BC) since he is unlikely to have studied under him at the young age of 14. However, γνωριμος can also mean "acquaintance", and the year of Zeno's death is by no means definite. Cf. Eratosthenes entry in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography (1971)

- ^ The Suda states he died at the age of 80, Censorinus (De die natali, 15) at the age of 81, and Pseudo-Lucian (Makrobioi, 27) at the age of 82.

- ^ Erastothenes (2010). Eratosthenes' "Geography". Fragments collected and translated, with commentary and additional material by Duane W. Roller. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14267-8.

- ^ Alfred, Randy (June 19, 2008). "June 19, 240 B.C.: The Earth Is Round, and It's This Big". Wired.

- ^ Entry ε 2898

- ^ See also Asimov, Isaac. Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, new revised edition. 1975. Entry #42, "Eratosthenes", Page 29. Pan Books Ltd, London. ISBN 0-330-24323-3. It was also asserted by Carl Sagan, 31 minutes into his Cosmos episode The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean

- ^ Oxford Reference (subscription required)

- ^ * p439 Vol. 1 William Woodthorpe Tarn Alexander the Great. Vol. I, Narrative; Vol. II, Sources and Studies0. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1948. (New ed., 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-521-53137-3)).

- ^ How did Eratosthenes measure the circumference of the earth?

- ^ Engels, Donald (Autumn 1984). "The Length of Eratosthenes' Stade". American Journal of Philology. 106 (3): 298–311. doi:10.2307/295030. JSTOR 295030.

- ^ Isaac Moreno Gallo (3–6 November 2004). "Roman Surveying" (PDF). translated by Brian R. Bishop. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-05.

- ^ There is a huge volume of Eratosthenes-got-it-right literature based on attacking the applicability of the standard 185 m stadium to his experiment. Among advocates: F. Hultsch, Griechische und Römische Metrologie, Berlin, 1882; E. Lehmann-Haupt, Stadion entry in Paulys Real-Encyclopädie, Stuttgart, 1929; I. Fischer, Q. Jl. R. astr. Soc. 16.2:152–167, 1975; Gulbekian (1987); Dutka (1993). The means employed include worrying various ratios of the stadium to the unstably defined "schoenus", or using a truncated passage from Pliny. (Gulbekian just computes the stadium from Eratosthenes' experiment instead of the reverse.) Nicastro (2008), however, uses statistical analysis of Eratosthenes' linear distances (as reported by Strabo) to establish a 95% probability that Eratosthenes used a stade between 153.5 and 162.4 meters, with the 185 m "Attic" stade well outside the 3-sigma confidence interval. A disproportionality of literature exists because some professional scholars of ancient science have regarded such speculation as special pleading and so have not bothered to write extensively on the issue. Skeptical works include E. Bunbury's classic History of Ancient Geography, 1883; D. Dicks, Geographical Fragments of Hipparchus, University of London, 1960; O. Neugebauer, History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy, Springer, 1975; J. Berggren and A. Jones, Ptolemy's Geography, Princeton, 2000. Some difficulties with the several arguments for Eratosthenes' exact correctness are discussed by Rawlins in 1982b page 218 and in his Contributions and Distillate. See also, at [1], "The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean", chapter 1 of Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, a TV series by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan and Steven Sotter (1978–1979), where a description of Eratosthenes' experiment is presented.

- ^ Mentioned by Hero of Alexandria in his Dioptra. See p. 272, vol. 2, Selections Illustrating the History of Greek Mathematics, tr. Ivor Thomas, London: William Heinemann Ltd.; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957.

Further reading

- Aujac, G. (2001). Eratosthène de Cyrène, le pionier de la geographie. Paris: Édition du CTHS. 224p.

- Bulmer-Thomas, Ivor (1939–1940). Selections Illustlating the History of Greek Mathematics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Cameron McPhail (2011). Reconstructing Eratosthenes' Map of the World: a Study in Source Analysis. A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Otago. Dunedin, New Zealand.

- Diller, A. (1934). “Geographical Latitudes in Eratosthenes, Hipparchus and Posidonius”. Klio 27(3): 258–269.

- Dorofeeva, A. V. (1988). "Eratosthenes (ca. 276–194 B.C.)". Mat. V Shkole (in Russian) (4): i.

- Dutka, J. (1993). "Eratosthenes' measurement of the Earth reconsidered". Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 46 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1007/BF00387726.

- El'natanov, B. A. (1983). "A brief outline of the history of the development of the sieve of Eratosthenes". Istor.-Mat. Issled. (in Russian). 27: 238–259.

- Fischer, I. (1975). "Another look at Eratosthenes' and Posidonius' determinations of the Earth’s circumference". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 16: 152—167.

- Fowler, D. H.; Rawlins, Dennis (1983). "Eratosthenes' ratio for the obliquity of the ecliptic". Isis. 74 (274): 556–562. doi:10.1086/353361.

- Fraser, P. M. (1970). "Eratosthenes of Cyrene". Proceedings of the British Academy. 56: 175–207.

- Fraser, P. M. (1972). Ptolemaic Alexandria. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Geus K. (2002). Eratosthenes von Kyrene. Studien zur hellenistischen Kultur- und Wissenschaftgeschichte. München: Verlag C.H. Beck. (Münchener Beiträge zur Papyrusforschung und antiken Rechtsgeschichte. Bd. 92) X, 412 S.

- Goldstein, B. R. (1984). "Eratosthenes on the "measurement" of the earth". Historia Math. 11 (4): 411–416. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(84)90025-9.

- Gulbekian, E. (1987). "The origin and value of the stadion unit used by Eratosthenes in the third century B.C". Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 37 (4): 359–363. doi:10.1007/BF00417008.

- Honigmann, E. (1929). Die sieben Klimata und die πολεις επισημοι. Eine Untersuchung zur Geschichte der Geographie und Astrologie in Altertum und Mittelalter. Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung. 247 S.

- Knaack, G. (1907). "Eratosthenes". Pauly–Wissowa VI: 358–388.

- Manna, F. (1986). "The Pentathlos of ancient science, Eratosthenes, first and only one of the "primes"". Atti Accad. Pontaniana (N.S.) (in Italian). 35: 37–44.

- Muwaf, A.; Philippou, A. N. (1981). "An Arabic version of Eratosthenes writing on mean proportionals". J. Hist. Arabic Sci. 5 (1–2): 174–147.

- Nicastro, Nicholas (2008). Circumference: Eratosthenes and the ancient quest to measure the globe. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-37247-7.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Eratosthenes", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Marcotte, D. (1998). “La climatologie d’Ératosthène à Poséidonios: genèse d’une science humaine”. G. Argoud, J.Y. Guillaumin (eds.). Sciences exactes et sciences appliquées à Alexandrie (IIIe siècle av J.C. – Ier ap J.C.). Saint Etienne: Publications de l'Université de Saint Etienne: 263–277.

- Pfeiffer, Rudolf (1968). History of Classical Scholarship From the Beginnings to the End of the Hellenistic Age. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Rawlins, D. (1982). "Eratosthenes' geodesy unraveled : was there a high-accuracy Hellenistic astronomy". Isis. 73 (2): 259–265. doi:10.1086/352973.

- Rawlins, D. (1982). "The Eratosthenes – Strabo Nile map. Is it the earliest surviving instance of spherical cartography? Did it supply the 5000 stades arc for Eratosthenes' experiment?". Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 26 (3): 211–219.

- Rawlins, D. (2008). "Eratothenes's large earth and tiny universe" (PDF). DIO. 14: 3–12.

- Roller, Duane W. (2010). Eratosthenes' Geography: Fragments collected and translated, with commentary and additional material. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14267-8.

- Shcheglov, D.A. (2004/2006). “Ptolemy’s System of Seven Climata and Eratosthenes’ Geography”. Geographia Antiqua 13: 21–37.

- Shcheglov, D.A. (2006). “Eratosthenes’ Parallel of Rhodes and the History of the System of Climata”. Klio 88: 351–359.

- Strabo (1917). The Geography of Strabo. Horace Leonard Jones, trans. New York: Putnam.

- Taisbak, C. M. (1984). "Eleven eighty-thirds. Ptolemy's reference to Eratosthenes in Almagest I.12". Centaurus. 27 (2): 165–167. Bibcode:1984Cent...27..165T. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1984.tb00766.x.

- Thalamas, A. (1921). La géographe d’Ératosthène. Versailles.

- Wolfer, E. P. (1954). Eratosthenes von Kyrene als Mathematiker und Philosoph. Groningen-Djakarta.

External links

- Bernhardy, Gottfried: "Eratosthenica" Berlin 1822 Reprinted Osnabruck 1968 (German text)

- Bernhardy, Gottfried: Eratosthenica Berlin, 1822 (PDF) (Latin/Greek)

- Eratosthenes' sieve in Javascript

- Eratosthenes' sieve as a simple algorithm

- About Eratosthenes' methods, including a Java applet

- How to measure the earth with Eratosthenes' method [dead link]

- How the Greeks estimated the distances to the moon and sun

- Eratosthenes on PBS.org

- Measuring the earth with Eratosthenes' method

- List of ancient Greek mathematecians and contemporaries of Eratosthenes

- New Advent Encyclopedia article on the Library of Alexandria

- Eratosthenes' sieve explored and visualised in Flash

- Eratosthenes' sieve in classic BASIC all-web based interactive programming environment

- Following in the footsteps of Eratosthenes : project fr:La main à la pâte.

- Open source Physics Computer Model about Eratosthenes estimation of radius and circumference of Earth

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 276 BC births

- 194 BC deaths

- 3rd-century BC Greek people

- Deaths by starvation

- Ancient Greek astronomers

- Ancient Greek geographers

- Ancient Greek music theorists

- Ancient Greek mathematicians

- Cyrenean Greeks

- Hellenistic Egyptians

- Number theorists

- Geodesists

- Librarians of Alexandria

- Geometers

- Ancient Greek poets

- Ancient Greek athletes

- 3rd-century BC poets