History of Warsaw: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

Binksternet (talk | contribs) Unreliable source per RSN |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

[[Image:Plac Teatralny w Warszawie, 1925.jpg|thumb|Theatre Square in Warsaw, ca. 1925: on the right - the [[Great Theatre, Warsaw|Great Theatre]], on the left - Jabłonowski's Palace (1818-1939 seat of President of Warsaw]] |

[[Image:Plac Teatralny w Warszawie, 1925.jpg|thumb|Theatre Square in Warsaw, ca. 1925: on the right - the [[Great Theatre, Warsaw|Great Theatre]], on the left - Jabłonowski's Palace (1818-1939 seat of President of Warsaw]] |

||

The first years of independence were very difficult: war havoc, hyperinflation and the [[Polish–Soviet War|Polish-Bolshevik War]] of 1920. In the course of this war, the huge [[Battle of Warsaw (1920)|Battle of Warsaw]] was fought on the Eastern outskirts of the city in which the capital was successfully defended and the [[Red Army]] defeated.<ref>{{en icon}} {{cite web |author= |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/466681/Poland/28213/From-the-Treaty-of-Versailles-to-the-Treaty-of-Riga#ref=ref397007&tab=active~checked%2Citems~checked&title=Poland%20%3A%3A%20From%20the%20Treaty%20of%20Versailles%20to%20the%20Treaty%20of%20Riga%20--%20Britannica%20Online%20Encyclopedia |title=Poland, History » Poland in the 20th century » From the Treaty of Versailles to the Treaty of Riga |work=www.britannica.com |publisher= |pages= |page= |date= |accessdate=2008-07-14}}</ref> Poland stopped on itself the full brunt of the Red Army and defeated an idea of the "[[Export of revolution|export of the revolution]]." |

The first years of independence were very difficult: war havoc, hyperinflation and the [[Polish–Soviet War|Polish-Bolshevik War]] of 1920. In the course of this war, the huge [[Battle of Warsaw (1920)|Battle of Warsaw]] was fought on the Eastern outskirts of the city in which the capital was successfully defended and the [[Red Army]] defeated.<ref>{{en icon}} {{cite web |author= |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/466681/Poland/28213/From-the-Treaty-of-Versailles-to-the-Treaty-of-Riga#ref=ref397007&tab=active~checked%2Citems~checked&title=Poland%20%3A%3A%20From%20the%20Treaty%20of%20Versailles%20to%20the%20Treaty%20of%20Riga%20--%20Britannica%20Online%20Encyclopedia |title=Poland, History » Poland in the 20th century » From the Treaty of Versailles to the Treaty of Riga |work=www.britannica.com |publisher= |pages= |page= |date= |accessdate=2008-07-14}}</ref> Poland stopped on itself the full brunt of the Red Army and defeated an idea of the "[[Export of revolution|export of the revolution]]."<ref>{{en icon}} {{cite web |author=Zdzisław G. Kowalski |url=http://www.archiwa.gov.pl/memory/sub_listakrajowa/index.php?va_lang=en&fileid=019 |title=Documents of the Battle of Warsaw 1920 |work=Memory of the World |publisher= |pages= |page= |date= |accessdate=2008-07-14}}</ref> Communist time table was slowed 24 years and countries of the Central Europe were spared from communist rule for a quarter of a century. Western Europe, where revolutionary fever was boiling over on the streets, was spared a bloody fight for survival. Unfortunately, political and military significance of this victory was never fully appreciated by Europeans. According [[Edgar Vincent, 1st Viscount D'Abernon|Lord d’Abernon]]: ''The history of contemporary civilization knows no event of greater importance than the Battle of Warsaw, 1920, and none of which the significance is less appreciated.''<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.electronicmuseum.ca/Soviet-Polish-War/spw_3.html |title=Vistula River Victory |work=www.electronicmuseum.ca |accessdate=14-07-2008 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080612214343/http://www.electronicmuseum.ca/Soviet-Polish-War/spw_3.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 12-06-2008}}</ref> To commemorate these events, the 15 August is celebrated in Poland as the Day of Polish Army. |

||

On 16 December 1922, in the gallery [[Zachęta]], [[Eligiusz Niewiadomski]], a painter with mental disorder, who belonged to the right-wing [[National Democracy]], assassinated the first President of Poland, [[Gabriel Narutowicz]], who had been elected five days earlier by Sejm. |

On 16 December 1922, in the gallery [[Zachęta]], [[Eligiusz Niewiadomski]], a painter with mental disorder, who belonged to the right-wing [[National Democracy]], assassinated the first President of Poland, [[Gabriel Narutowicz]], who had been elected five days earlier by Sejm. |

||

Revision as of 04:07, 2 July 2012

The history of Warsaw is mostly synonymous with the history of Poland. First fortified settlements on area of today Warsaw were founded in the 9th century and for many centuries coincided with the development of what is today known as the Warsaw Old Town.

During this time the city has experienced numerous plagues, invasions, devastating fires and administrative restrictions on its growth. The most crucial of those events included the Deluge, the Great Northern War (1702, 1704, 1705), War of the Polish Succession, Warsaw Uprising (1794), Battle of Praga and the Massacre of Praga inhabitants, November Uprising, January Uprising, World War I, Siege of Warsaw (1939) and aerial bombardment, Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw Uprising (which in the aftermath nearly reduced all of the city to rubble by German occupiers).

The city was a site of other significant but less destructive events. It was the site of election of Polish kings, meeting of Polish parliament (Sejm), and events such as the Polish victory over the Bolsheviks at the Vistula, during the Battle of Warsaw (1920). Yet it has still grown to the multicultural capital of a modern European state and a major commercial and cultural centres of Central Europe.

Early history

The area covered by modern Warsaw had been inhabited for at least 1400 years. Several archaeological findings date back to the times of the Lusatian culture.

The first fortified settlements on the site of today's Warsaw were Bródno (9th/10th century), Kamion (11th century) and Jazdów (12th/13th century).[1] Bródno was a small settlement in the north-eastern part of today’s Warsaw, buried about 1040 during the uprising of Miecław – one of the Mazovian local princes. Kamion was established about 1065 close to the today’s Warszawa Wschodnia station (today – Kamionek estate), Jazdów – before 1250 by the today’s Sejm. Jazdów was raided twice – in 1262 by Lithuanians, in 1281 by the Płock prince Bolesław II of Masovia. Then, a new similar settlement was established on the site of a small fishing village called Warszowa, ca. 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) north of Jazdów – by the same prince Bolesław II. The Bolesław’s brother and successor, Konrad II, built a wooden castellan, which was buried – again by the Lithuanians. On this place, the prince ordered the building of a brick church, which obtained the name of St. John and became a cathedral.

The first historical document attesting to the existence of a Warsaw castellan dates to 1313.[3] Fuller information about the age of the city is contained in the court case against the Teutonic Knights which took place in Warsaw cathedral in 1339.[3] In the beginning of the 14th century it became one of the seats of the Dukes of Masovia, becoming the capital of Masovia in 1413 (prince Janusz II).[1] Fourteenth-century Warsaw's economy rested on crafts and trade. The townsmen, of uniform nationality at the time, were marked by a great disparity in their financial status.[3] At the top were the rich patricians while the plebeians formed the lower strata.[3]

In that time, in Warsaw lived about 4500 people. During the 15th century, the town became to spread – beyond the northern town wall a settlement came into existence, which was called New Town, whereas the already existing settlement was called Old Town. Those two towns had their own town charters and own governments. The aim of establishing a new town was to regulate the settling of new people who weren’t allowed to settle in Old Town (mainly Jews) [4]

In 1515, during Muscovy-Lithuanian War fire incented probably by Russian agents burned great part of Old Warsaw.[5] The differentiation and the growing social contrasts resulted in 1525 in the first revolt of the poor of Warsaw against the rich and the authority they exercised.[3] As a result of this struggle the so-called third order was admitted to the city’s authorities and shared power with the bodies formed by the patricians: the council and the assessors.[3] The story of Warsaw populace's struggle for social liberation dates from that first demonstration in 1525.[3]

Upon the extinction of the local ducal line, the duchy was reincorporated into the Polish Crown in 1526 (according to the gossips, the last Mazovian prince Janusz III was poisoned on the orders of Polish Queen, Bona Sforza, King Sigismund I).[1]

1526-1700

In 1529, Warsaw for the first time became the seat of the General Sejm, permanent since 1569.[1] By this reason, an Italian architect, Giovanni di Quadro, rebuilt the King’s Castle in the Renaissance style. The incorporation of Mazovia into the Polish Crown spelt fast economic development, which is demonstrated by a population growth: in that time there lived 20,000 people, whereas 100 years earlier only ca. 4500.[4]

In 1572 died the last king from the Jagiellon dynasty, Sigismund II Augustus. On the Sejm’s seat in 1573, there was passed that from this moment on Polish kings would be elected by gentry. On the same seat, there was also passed so-called Warsaw Confederation which formally established religious freedom in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The first “free election” (in Polish: wolna elekcja) was held in April and May 1573 in Kamień (today’s Kamionek estate, close to the Wschodnia Station). The next elections, however (already in 1575, when Stephen Báthory became a Polish king), were held in another Warsovian suburb – at Wielka Wola (now that city's western, Wola district). The stormiest elections were those of 1575 and 1587, when matters came to blows among the divided nobles. Following an election, the king-elect was obliged to sign pacta conventa (Latin: "agreed-upon agreements") - laundry lists of campaign promises, seldom fulfilled - with his noble electors. The agreements included "King Henry's Articles" (artykuły henrykowskie), first imposed on Prince Henri de Valois (in Polish, Henryk Walezy) at the outset of his brief reign (upon the death of his brother, French King Charles IX, Henri de Valois fled Poland by night to claim the French throne).

Due to its central location between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's capitals of Kraków and Vilnius, as well as relatively closely to Gdańsk, from where Sweden was always threatening, Warsaw became the capital of the Commonwealth and at the same time of the Polish Crown in 1596, when King Sigismund III Vasa moved the court from Kraków.[1] The King’s decision had been brought forward by the fire of Cracovian Wawel Castle. The royal architect, Santa Gucci, started to rebuilt the Warsovian Castle in the Baroque style, therefore the King live there only temporarily; but in 1611 moved here for good. At the time of the transformation of Warsaw from one of the main Polish towns into the country's capital, it already numbered some 14,000 inhabitants. The old walled city had 169 houses; the new Warsaw outside the walls numbered 204 houses, while the suburbs had as many as 320.[3] In 1576, the first permanent bridge was built on Vistula; it was destroyed in 1603 by an ice floe and until 1775 did not exist any permanent connection between Warsaw and Praga on the Vistula’s right bank.

In the following years the town expanded towards the suburbs. Several private independent districts were established, the property of aristocrats and the gentry, which were ruled by their own laws. Such districts were called jurydyka. They were settled by craftsmen and tradesmen.[3] One of these “jurydykas” was Praga, which granted a city charter in 1648. The peak of their development came in the wake of Warsaw's revival after the Swedish invasion which had seriously ravaged the city.[3] Three times between 1655-1658 the city was under siege and three times it was taken and pillaged by the Swedish, Brandenburgian and Transylvanian forces.[1][6] They stole many valuable books, pictures, sculptures and other works of art - mainly, the Swedish troops. The mid-17th century architecture of the Old and New Towns survived until Nazi invasion.[3] The style was late Renaissance with Gothic ground floors preserved from the fire of 1607.[3] In the 17th and early part of the 18th century, during the rule of the great nobles oligarchy, magnificent Baroque residences rose all around Warsaw.[3] In 1677, King John III Sobieski started to build his Baroque residence in Wilanów, a village ca. 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of Old Town.

1700-1795

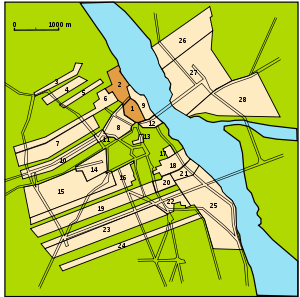

Warsaw jurydykas  Template:Multicol1. Old Town 2. New Town 3. Szymanowska 4. Wielądka 5. Parysowska 6. Świętojerska 7. Nowolipie 8. Kapitulna 9. Dziekania 10. Leszno 11. Tłumackie 12. Mariensztadt 13. Dziekanka 14. Wielopole Template:Multicol-break 15. Grzybów 16. and 24. Bielino 17. Stanisławów 18. Aleksandria 19. Nowoświecka 20. Ordynacka 21. Tamka-Kałęczyn 22. Bożydar-Kałęczyn 23. Nowogrodzka 24. and 16. Bielino 25. Solec 26. Golędzinów 27. Praga 28. Skaryszew-KamionTemplate:Multicol-end |

A number of political circumstances ensured that after the death of King John III’s, the Polish Kingdom entered into a period of decline relative to the other powers of Europe. A new king, the Saxon Prince-Elector Frederic Augustus was elected in 1697, who took the name Augustus II. The new monarch was more concerned with the fortunes of his mother country, Saxony, than of Poland. At the same time, the Polish gentry began to intensively fight for their own rights against the Crown with less thought for maintaining the kingdom’s position obtained in 17th century. Moreover, the rulers of the neighboring Russia (Peter I the Great) and Sweden (Charles XII) were gradually extending the territories of their states and strengthening their power. In 1700, the Great Northern War broke out between these two states; Augustus II recklessly joined it at the Peter I’s side. The decentralized Polish Crown lacked sufficient power to assert itself in the Northern War, which led Poland to becoming a battlefield between the two kings. Warsaw was besieged several times – for the first time, in 1702, by the Swedish troops.[7] The city suffered severely from the Swedish occupation. Under the Swedish influence, in June 1704 the Polish gentry dethroned Augustus II and at Wielka Wola elected a new king - the pro-Swedish Poznań Voivod Stanisław Leszczyński.[7] Shortly afterwards, the tides of war changed and on September 1, 1704 Warsaw was retaken by Saxon Army of Augustus II after five days of a severe artillery bombardment.[8][9] Augustus in turn lost Warsaw after being defeated in a battle fought on 31 July 1705. In this action, which took place between today's Warszawa Zachodnia Station and Wielka Wola, 2,000 Swedish troops defeated 10,000 soldiers of the Polish-Lithuanian-Saxon army Only now Stanisław Leszczyński could be officially crowned, which took place in October of that year. In 1707, by virtue of the peace treaty between Augustus II and Charles XII, Russian troops entered Warsaw. After two months, Russian forces were removed from Warsaw. Several times during the Northern war the city was obliged to pay heavy contributions. Leszczyński reigned until 1709, when Russia defeated Sweden in the battle of Poltava, forcing the Swedish army to leave Poland. Following the Swedish defeat, Augustus II once again the King of Poland.[8][9] From 1713 onwards, the Russian and Saxon troops were permanently stationed in Warsaw, which led to an oppressive occuption. Besides for the tribulations of war, Warsaw was hit by pest (1708), flood (1713) and poor crops.

Augustus II died in February 1733. In September, the Polish gentry again elected as king Stanisław Leszczyński, but it did not matched the political interests of Austria and Russia, which, one month later, forced the Sejm to elect the Augustus II’s son – Augustus III. Conflicts of interests between the Leszczyński camp and its patrons Sweden and France and the followers of Augustus III and his patrons Russia and Austria led to the War of the Polish Succession, where Poland again was not more than a battlefield; Warsaw again suffered marches and occupations. As a result of the war, Augustus III remained king and Leszczyński fled to France. Despite the political weakness of the state, the Saxon period was the time of development for Warsaw. The Saxon kings brought many German architects, who rebuilt Warsaw in the style similar to Dresden. In 1747 the Załuski Library was established in Warsaw by Józef Andrzej Załuski and his brother, Andrzej Stanisław Załuski. It was considered to be the first Polish public library[10] and one of the largest libraries in the contemporary world.[11] In all of Europe there were only two or three libraries, which could pride themselves on having such a vast book collection.[12] The library initially had about 200,000 items, which grew to about 400,000 printed items, maps and manuscripts[11][13] by the end of the 1780s. It also accumulated a collection of art, scientific instruments, and plant and animal specimens.

In 1740 Stanisław Konarski, a Catholic priest, founded Collegium Nobilium – the university for noblemen’s sons, which is considered as the predecessor of the University of Warsaw. In 1742, the City Committee was established, which was responsible for building of pavements and sewage system. But large parts of the greater Warsaw urban area remained out of control of the municipal authorities. Only in 1760’s did the entire Warsaw urban area come under one administration – thanks to efforts of the future President Jan Dekert (in Poland, the mayors of bigger cities are called Presidents). Before, the greater Warsaw urban area was divided into 7 districts.[4]

In 1764, a new Polish king was elected, the pro-Russian Stanisław August Poniatowski. Poland became practically a Russian protectorate after his election. In 1772, the first partition of Poland took place. Polish historians state that the partition was the necessary shock for the Polish gentry to “weak up” and start to think about the future of the country. Owing to the reforming mood, the Enlightenment excised massive influence in Poland and along with it, new ideas of the improvement of Poland. In 1765, the King established Korpus Kadetów – the first secular school in Warsaw (despite of its name it was not a military school). In 1773, the first ministry of education on the world came into existence – the Commission of National Education (Komisja Edukacji Narodowej). In 1775, a new bridge on the Vistula was built, which existed until 1794.

This time marked a new and characteristic stage in the development of Warsaw.[3] It turned into an early-capitalistic principal city. The growth of political activity, development of progressive ideas, political and economic changes – all this exercised an impact on the formation of the city whose architecture began to reflect the contemporary aspirations and trends.[3] Factories developed, the number of workers increased, the class of merchants, industrialists and financiers expanded.[3] At the same time there was a large-scale migration of peasants to Warsaw.[3] In 1792, Warsaw had 115,000 inhabitants as compared with 24,000 in 1754.[3] These changes brought about the development of the building trade. New noblemen's residences were put up, the middle class built its own houses which showed a marked social differentiation.[3] The residences of the representatives of the wealthiest stratum – the big merchants and bankers – matched those of the magnates.[3] A new type of city dwellings developed, catering to the needs and tastes of the bourgeoisie. The artistic medium for all these buildings was that of antiquity, which, although its different social origin was not analyzed at the time, expressed the progressive ideas of the Enlightenment.[3]

In 1788, the Sejm gathered to discuss the ways to improve the political situation and to regain the full independence. As Poland was more or less a de facto Russian protectorate, the Empress Catherine II had to give permission for session. Catherine had no objection because she did not foresee any danger, and besides she needed a Polish help in the war against Turkey. But as the result the Sejm in Warsaw (called Great because of the duration of the session) passed the Constitution of May 3, 1791, which the British historian Norman Davies calls "the first constitution of its kind in Europe".[14] It was adopted as a "Government Act" (Polish: Ustawa rządowa) on that date by the Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was in effect for only a year. The Russian-Turkish war had finished and Empress Catherine could turn her attention to Polish affairs. The result was the Second Partition of Poland of 1793, which in turn led to the 1794 Warsaw Uprising. It was an insurrection by the city's populace early in the Kościuszko Uprising. Supported by the Polish Army, it aimed to throw off Russian control of the Polish capital. The uprising began on April 17, 1794, soon after Tadeusz Kościuszko's victory at Racławice.

After the Battle of Maciejowice General Tadeusz Kościuszko was captured by the Russians. The internal struggle for power in Warsaw and the demoralisation of the city's population prevented General Józef Zajączek from finishing the fortifications surrounding the city both from the east and from the west. At the same time the Russians were making their way towards the city. The Russian forces reached the east outskirts of Warsaw on November 3, 1794. The heavy fighting lasted for four hours and resulted in a complete defeat of the Polish forces. Only a small part managed to evade encirclement and retreated to the other side of the river across a bridge; hundreds of soldiers and civilians fell from a bridge and drowned in the process. After the battle ended, the Russian troops, against the orders given by General Alexander Suvorov before the battle, started to loot and burn the entire borough of Warsaw (allegedly in revenge for the slaughter or capture of over half the Russian Garrison in Warsaw[15] during the Warsaw Uprising in April 1794, when about 2,000 Russian soldiers died[16]). Almost all of the area was pillaged, burnt to the ground and many inhabitants of the Praga district were murdered. The exact death toll of that day remains unknown, yet it is estimated up to 20,000 men, women and children were killed.[17] In Polish history and tradition, these events are called “slaughter of Praga”. A British envoy, William Gardiner, wrote to the British Prime Minister that “the attack on the Praga’s lines of defense was accompanied by the most gruesome and totally unnecessary barbarousness”.[18]

After the fall of Kościuszko Uprising, The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was finally divided between the three neighbors (the 3rd partition, 1795): Russia, Prussia and Austria. Warsaw found itself in the Prussian part and became the capital of the province South Prussia (Südpreussen).

There was one more result of the Great Sejm works – directly concerning Warsaw: on 21 April 1791 it passed the City Act, which cancelled jurydykas. Since that time, Warsaw and its former jurydykas have constituted a homogeneous urban organism under one administration. As a memento of this event, April 21 is celebrated as the Warsaw Day.

1795-1914

Warsaw remained the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1795, when it was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia to become the capital of the province of South Prussia. Liberated by Napoleon's army in 1806, Warsaw was made the capital of the newly created Duchy of Warsaw.[1] Following the Congress of Vienna of 1815, Warsaw became the center of the Congress Poland, a constitutional monarchy under a personal union with Imperial Russia.[1] During this period under the rule of the relatively liberal Russian Emperor Alexander I, Warsaw experienced much growth such as the founding of the Royal University of Warsaw was established (1816) and what is today’s main street of the city – Aleje Jerozolimskie – was marked out. In 1818, the Town Hall on the Old Town Market was pulled down, because it was too small for the city which had expanded after incorporation of the jurydykas. The city’s authorities moved to Jabłonowski’s Palace (by the Great Theater), where it stayed until World War II.

Following the repeated violations of the Polish constitution by the Russians (especially after the Alexander I’s death, when the reactionary Nicholas I assumed the power), the 1830 November Uprising broke out. It started with the assault on Belvedere - the residence of Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich, the commander-in-chief of Polish army and de facto viceroy of the Congress Poland – as well as at the Arsenal. The 1830 uprising led to the Polish-Russian war (1831), whose the greatest battle held place on 25 February 1831 in Grochów – a village which is in the modern northern part of the district Praga Południe. Because of the stalling of Polish commanders the war ended in the defeat and in the curtailment of the Kingdom's autonomy.[1] The Emperor established the military administration in Warsaw. An estate of pretty manors on the north of New Town was eradicated and on this place the Citadel was built, where was a fortress and prison. The Sejm was suspended, the Polish army – dissolved and the University – closed.

With time, the Emperor’s severe attitude to Poland softened and Warsaw could develop again. In 1845, the first railway on the Congress Poland territory and the second in the Russian Empire was opened – the Warsaw-Vienna Railway, to standard gauge; in 1862 – the Warsaw-Saint Petersburg Railway (to broad gauge). In 1875 and 1908, two railway bridges were built, whereas in 1864 – the first iron road bridge on stone supports: Most Kierbedzia – one of the most modern bridges in Europe of that time. Nowadays, the Śląsko-Dąbrowski bridge lies at the same supports. Only then the city’s authorities started to rebuilt Praga, which had been heavily damaged during the Kościuszko’s and November Uprisings as well as by Napoleon’s war. In 1862, the University was opened again, in 1898 the Nicholas II Technical Institute (the Warsaw Technical University’s predecessor) was established.

Warsaw flourished in the late 19th century under Mayor Sokrates Starynkiewicz (1875–92), a Russian-born general appointed by Tsar Alexander III. Under Starynkiewicz Warsaw saw its first water and sewer systems designed and built by the English engineer William Lindley and his son, William Heerlein Lindley, as well as the expansion and modernization of horsecars, street lighting and gas works.[1] Starynkiewicz also founded the Bródno Cemetery (1884) – even nowadays one of the biggest European cemeteries. As a remembrance of the great President, one of the Warsovian squares bears the name of Starynkiewicz – although he was the representative of the Russian authorities.

In 1904, the first power plant was built, which enabled the city to install electric lamps on the streets and – in 1908 –to open the first electric tram route. In 1914, the third bridge was opened – Most Józefa Poniatowskiego.

But Warsaw's development was accompanied by an intensive assault on Polish national identity. The Russian authorities closed Polish schools and built more and more Orthodox churches. These acts met a strong opposition. On 27 February 1861 a Warsaw crowd protesting the Russian rule over Poland was fired upon by the Russian troops.[20][21] Five people were killed. On 22 January 1863 a new uprising broke out. The Underground Polish National Government resided in Warsaw during January Uprising in 1863–4.[21] However, this uprising was mainly in the character of guerilla, therefore Warsaw did not distinguish itself in it. But, as a penalty, President Kalikst Witkowski, the Russian general and predecessor of Sokrates Starynkiewicz, constantly imposed tributes on Warsaw. The last serious riots took place in 1905 (after the St. Petersburg’s “bloody Sunday”), when the Cossacks and police fired to the people demonstrating in Warsaw. In 1897 Warsaw was 56.5% Polish, 35.8% Jewish and 4.9% Russian.[22]

World War I

On 1 August 1915 the German army entered Warsaw. The Russians, while retreating, demolished all of the Warsovian bridges – along with the Poniatowski Bridge, opened 18 months earlier – and took with themselves the equipment of the factories, what made the situation in Warsaw much more difficult. The German authorities, headed by gen. Hans von Beseler, needed the Polish support in the war against Russia, therefore took steps proving its friendly attitude to Poles – for example, reintroduced the possibility to teach in Polish: in 1915 they opened the Technical University, Warsaw School of Economics and Warsaw University of Life Sciences.

However, the most important decision for a city development was to incorporate the suburbs. The Russian authority hadn't allowed to extend the Warsaw’s area, because it was forbidden to cross the double line of forts, surrounding the city. By this reason, at the beginning of World War I on the area of today's Śródmieście and the old part of Praga (ca. 33 square kilometres (13 sq mi) 750,000 people lived. In April 1916, the Warsaw territory extended to 115 square kilometres (44 sq mi).

In autumn of 1918, the revolution broke up in Germany. On 8 November, the German authorities left Warsaw. On 10 November Józef Piłsudski came at the Warsaw-Vienna Station. On 11 November the Regency Council passed him all military authority, whereas on 14 November – all civil authority. By this reason, the 11 November 1918 is celebrated as the beginning of the Poland’s independence. Warsaw became the capital of the Poland.

1918-1939

The first years of independence were very difficult: war havoc, hyperinflation and the Polish-Bolshevik War of 1920. In the course of this war, the huge Battle of Warsaw was fought on the Eastern outskirts of the city in which the capital was successfully defended and the Red Army defeated.[23] Poland stopped on itself the full brunt of the Red Army and defeated an idea of the "export of the revolution."[24] Communist time table was slowed 24 years and countries of the Central Europe were spared from communist rule for a quarter of a century. Western Europe, where revolutionary fever was boiling over on the streets, was spared a bloody fight for survival. Unfortunately, political and military significance of this victory was never fully appreciated by Europeans. According Lord d’Abernon: The history of contemporary civilization knows no event of greater importance than the Battle of Warsaw, 1920, and none of which the significance is less appreciated.[25] To commemorate these events, the 15 August is celebrated in Poland as the Day of Polish Army.

On 16 December 1922, in the gallery Zachęta, Eligiusz Niewiadomski, a painter with mental disorder, who belonged to the right-wing National Democracy, assassinated the first President of Poland, Gabriel Narutowicz, who had been elected five days earlier by Sejm.

The other event was the May Coup d’Etat (1926). On 12 May, Marshall Józef Piłsudski, displeased with the situation in Poland and in particular with the appointment of a new government, arrived on Warsaw from his residence in Sulejówek (small town at the east of Warsaw) at the head of the faithful troops. On the Poniatowski Bridge, he talked a bit with the President Stanisław Wojciechowski, who was trying to convince him to give up the action – but unsuccessfully. The next day, the Piłsudski’s troops forcibly conquered Warsaw and forced the government and Wojciechowski to resign. During the coup, as a result of the street fighting almost 400 people died – but mostly they were the rubbernecks who wanted to watch the fighting.[26] The May Coup started the 13-year period of sanation - the authoritarian rules of Piłsudski’s camp. Although Piłsudski himself never accepted the office of President (but twice was Prime Minister), always played a preponderant role in Polish political life.

In 1925, there lived 1,000,000 people in Warsaw. In the next 5 years, the city’s wealth doubled thanks to a good economic situation on the world. It enabled to build new, broad streets as well as a new airport. The first, temporary airport was opened in 1921 in the park Pole Mokotowskie, the second – permanent – in Okęcie, where it operates till today. Besides, the city’s government worked out the planes of metro (the realization was hampered by the outbreak of World War II) and opened the first radio station whose range covered almost all the Polish territory.

In 1934, the sanation camp suspended the Warsaw’s government and appointed Stefan Starzyński as President of Warsaw. He was a faithful supporter of “sanation” - at the beginning of his presidency consequently expelled all officials attached to his predecessor.[27] But he was also an efficient official – stabilized the city’s budget, fought against corruption and bureaucracy, smartened up the city. However, the Poles remember him mainly due to his heroic behavior during September Campaign.

World War II

The first bombs felt on Warsaw already on 1 September 1939. Unfortunately, the most important representatives of civil and military administration (along with the Army’s Commander-in-Chief, Marshall Edward Rydz-Śmigły) escaped to Romania, taking with themselves lot of equipment and ammunition. To stop the chaos, President Starzyński seized full civil power, although he had no entitlement to do this. To prevent public order, he appointed the Citizen Guard. All time he supported the people’s spirit in radio speeches. On 9 September, the German tank divisions attacked Warsaw from south-west, but the defenders (with a lot of civil volunteers among them) managed to stop them in the district Ochota. But the situation was hopeless – the Germans threw so many divisions that sooner or later they would conquer the city anyway, all the more so because on 17 September the Soviets invaded the east part of Poland. Three days later the German encirclement around Warsaw closed. On 17 September, the Royal Castle burnt down, on 23. – the power plant. On 27 September Warsaw surrendered and on 1 October the Germans went into the city. Generally, in September 1939 died in Warsaw ca. 31,000 people (among them 25,000 civilians) and 46,000 was injured (20,000 civilians). 10% of buildings were destroyed.[8] On 27 October, the Germans arrested President Starzyński and deported him to the Dachau concentration camp, where he died in 1943 or 1944 (the exact date is still unknown).

During the Second World War, central Poland, including Warsaw, came under the rule of the General Government, a Nazi colonial administration. Germans planned destruction of the Polish capital before the start of war.[28] On 20 June 1939 while Adolf Hitler was visiting an architectural bureau in Würzburg am Main, his attention was captured by a project of a future German town – "Neue deutsche Stadt Warschau".[29] As early as 1939 Hitler approved of a plan known as the Pabst Plan which envisaged changing Warsaw into a provincial German city.[28] All higher education institutions were immediately closed. Since the first days the German authorities had arrested and executed the Poles or had taken them to the concentration camps. The executions were being carried out mainly in the forests around Warsaw (e.g. in Kampinos Forest or Kabaty Woods), but later – publicly on streets (today, there’s a lot of small monuments in Warsaw, commemorating those crimes). Since the beginning of the occupation, the Nazis had organized so-called łapanka`s: it consisted in sudden and accurate surrounding of a chosen place (for example, a railway station) and arresting all of the people who by accident were there (passing by or living; in Polish “łapać” – to catch). Such actions were being carried out also in the other occupied European countries, but not on such scale as in Poland. The arrested people were being deported either to the concentration camps or on forced work to Germany. From 1943, a concentration camp existed also in Warsaw – KL Warschau. Until August 1944, about 200,000 Poles died in gas chambers.

Since October 1940, the Germans had been deported Warsaw's entire Jewish population (several hundred thousand, some 30% of the city) to the Warsaw Ghetto.[30] They herded ca. 500,000 people on the area of ca. 2.6 square kilometres (1.0 sq mi). The Jews were dying not only because of executions but also hunger (the daily food ration for one Jew was only 183 kcal).[8] Since October 1941, every Jew who had left the Ghetto as well as the Pole who had been helping in any way the Jews (e.g. threw food over the Ghetto wall), had been punished with death.

When the order came to annihilate the Ghetto as part of Hitler's "Final Solution" on April 19, 1943, Jewish fighters launched the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.[31] Despite being heavily outgunned and outnumbered, the Ghetto held out for almost a month.[31] When the fighting ended, almost all survivors were massacred, only few managed to escape or hide.[31][32] Almost all the leaders of the uprising committed suicide – including the principal, Mordechaj Anielewicz (only one survived – Marek Edelman). The commander of Verbrennungs und Vernichtungskommando ("Burning and Destruction Detachments"), Jürgen Stroop, destroyed the Ghetto so completely that even the house walls did not remain and after the war Poles did not clean the ruins but “filled up” them with soil and smoothed, making small mounds, on which they could build houses. Nowadays it’s very well noticeable.

By July 1944, the Red Army was deep into Polish territory and pursuing the Germans toward Warsaw.[33] Knowing that Stalin was hostile to the idea of an independent Poland, the Polish government-in-exile in London gave orders to the underground Home Army (AK) to try to seize the control of Warsaw from the Germans before the Red Army arrived. Thus, on 1 August 1944, as the Red Army was nearing the city, the Warsaw Uprising began.[33]

The Poles believed that Stalin would help them in a common struggle against Nazism but it did not happen. Despite that the Red Army approached the right bank of Vistula (on 14 August it conquered Praga), at the news of the uprising it stopped. Admittedly, Stalin sent two tank divisions which established a bridgehead on the left bank, but the soldiers had no experience in street fights and did not manage to keep the positions; sending intentionally the inexperienced troops, Stalin did not give help the insurgents – because he had not intended to do so - but could later repel the charges that he had not help the uprising.

The armed struggle, planned to last 48 hours, went on for 63 days (till 2 October). Eventually the Home Army fighters and civilians assisting them were forced to capitulate.[33] They were transported to the PoW camps in Germany, while the entire civilian population was expelled.[33]

The Nazis then essentially demolished Warsaw. Hitler, ignoring the agreed terms of the capitulation, ordered the entire city to be razed to the ground and the library and museum collections taken to Germany or burned.[33] Monuments and government buildings were blown up by special German troops known as Verbrennungs und Vernichtungskommando ("Burning and Destruction Detachments").[33] About 85% of the city had been destroyed, including the historic Old Town and the Royal Castle.[34] In the uprising, ca. 170,000 people died, from among which only 16,000 were insurgents. The civilians (ca. 650,000) were deported to the transit camp in Pruszków (Durchgangslager Pruszków).

On January 17, 1945 - after the beginning of the Vistula–Oder Offensive of the Red Army - Soviet troops entered the ruins of the city of Warsaw, and liberated Warsaw's suburbs from German occupation. The city was swiftly taken by the Soviet Army, which rapidly advanced towards Łódź, as German forces regrouped at a more westward position. In general, during the German occupation (1939–45) ca. 700,000 people died in Warsaw, i.e. more than all Americans and Brits.[35] The material looses were about 45 billion dollars.[36]

Those soldiers of the Home Army, who had survived the war, were arrested by the Soviet secret police (NKVD), then either executed or deported to Siberia.

Modern times

In 1945, after the bombing, the revolts, the fighting, and the demolition had ended, most of Warsaw lay in ruins. Next to the remnants of Gothic architecture the ruins of splendid edifices from the time of Congress Poland and ferroconcrete relics of prewar building jutted out of the rubble.[3]

On 17 January 1945, the Soviet troops entered the right part of Warsaw and on 1 February 1945 proclaimed the People’s Republic of Poland (de facto proclamation had taken place in Lublin, on 22 July 1945). At once, there was established the Bureau of Capital’s Rebuilding. Unfortunately, the architects working in the Bureau, blinded by the ideas of functionalism and supported by a Communist regime set up by the conquering Soviets, decided that Warsaw had to be renewed in modern style, with large free areas – so, they ordered to demolish still existing buildings or those which yet could be rebuilt. But not all of those crazy ideas came off – in 1953, the Old Town and the Royal Route were reconstructed, in such a form like they had looked like before the war (what was possible mainly thanks to numerous pictures of the old Warsaw, painted for example by Canaletto). On the other hand, due to the lack of the “original” residents, the houses were settled by “common people” which often did not know how to behave themselves or how to keep the houses properly. But the government did not make the decision about complicated and expensive rebuilding of the Royal Castle.

The rebuilding of the Old Town was an achievement on a global scale. In 1980, UNESCO appreciated the efforts and inscribed Old Town onto UNESCO's World Heritage list.[37]

The symbols of the new Warsaw were: the East-West Route Tunnel ("Trasa W-Z") – the tunnel under the Old Town (1949); the MDM estate (1952) – typical example of the architecture of socialist realism; Palace of Culture and Science (PKiN, 1955) – the symbol of Soviet rule, in that time the second tallest building in Europe, very similar to so-called "Seven Sisters" in Moscow; the 10th-Anniversary Stadium (1955). Especially the construction of the MDM estate and PKiN demanded to demolish the existing buildings. But it must be emphasized that the today’s Warsaw has one of the best street nets in Europe (leaving aside a bad condition of the roads and badly planned crossroads) – what was possible only thanks to the earlier demolition of houses.

In 1951, Warsaw was significantly enlarged again to address the housing shortage: from 118 square kilometres (46 sq mi) to 411 square kilometres (159 sq mi). In 1957, the town Rembertów was incorporated. On the incorporated areas, the city’s government ordered the building of mainly large prefabricated housing projects, typical for Eastern Bloc cities.

The Soviet presence, symbolized by the Palace of Culture and Science, turned out to be very acute. The Stalinism lasted in Poland until 1956 – like in USSR. The leader (First Secretary) of the Polish Communist party, (PZPR), Bolesław Bierut, suddenly died in Moscow during the 20th Congress of CPSU in March – probably from a hearth attack. Already in October, the new First Secretary, Władysław Gomułka, in a speech during a rally on the square in front of the PKiN supported the regime liberalization (so-called "thaw"). At first, Gomułka was very popular, because he also had been imprisoned in Stalinist prisons and as he had taken up the office of PZPR’s leader, he promised a lot – but the popularity passed pretty fast. Gomułka was gradually tightening the regime. In January 1968, he forbade to put on Dziady – the classical drama by Mickiewicz, full of anti-Russian allusions. That was "the last drop of bitterness": then students went out on the Warsaw streets and gathered by the monument to Mickiewicz to protest against censorship. The demonstrations spread throughout all the country, the protesting people were arrested by police. This time, the students were not supported by workers – but two years later, when in December 1970 the army fired at the protesting people in Gdańsk, Gdynia and Szczecin, those two social groups already cooperated with each other – and that was the end of Gomułka.

The successor of Gomułka was Edward Gierek. Comparing to the grey Gomułka-time, Gierek's rules looked pretty well – also for Warsaw. Already on the beginning Gierek agreed to rebuild the Royal Castle. Gomułka till the end of his life was against this idea for he was convinced that the Castle is a symbol of the bourgeoisie and feudalism. The rebuilding started in 1971, finished in 1974. In the same year, the building of Trasa Łazienkowska (Łazienkowska Route) was completed – the route and bridge connecting the region of Warszawa Zachodnia Station and the Grochów estate; the broad street on the right bank (Praga) has been named Aleja Stanów Zjednoczonych (The United States Avenue). The next important investments from the Gierek-times are: the Warszawa Centralna Station (1975 – nowadays the biggest station in Warsaw) and the broad, dual carriageway Warsaw-Katowice, which even now is called "Gierkówka" (in a choice of the destination point, pretty significant was the fact that Gierek himself was born in Silesia – in Sosnowiec). But the prosperity of the Gierek-times was grounded on a very fragile foundation: Gierek took out lot of loans from abroad and did not know how to manage them efficiently, hence from time to time crises and workers' riots kept recurring. The first more serious was in 1976, when the workers from Radom and Ursus were striking; that latter city bordered on Warsaw from west, there has been a big tractor factory. As a penalty, Ursus was incorporated into Warsaw as a part of the district Ochota; Warsaw expanded by 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi).

In the crisis of the 1980s and hard time of martial law, John Paul II's visits to his native country in 1979 and 1983 brought support to the budding Solidarity movement and encouraged the growing anti-communist fervor there.[38] In 1979, less than a year after becoming pope, John Paul celebrated Mass in Victory Square in Warsaw and ended his sermon with a call to "renew the face" of Poland: Let Thy Spirit descend! Let Thy Spirit descend and renew the face of the land! This land![38] These words were very meaningful for the Polish citizens who understood them as the incentive for the democratic changes.[38]

From February to April 1989, the representatives of the Polish government and "Solidarity" were carried on the negotiations at the Round Table in the Namiestnikowski Palace in Warsaw. The result was an agreement of the government to the participation of "Solidarity" in the Sejm elections, which were appointed at 4 June. "Solidarity" won all seats for which it could compete according to the Round Table Agreement. It was the beginning of big changes for all Europe.

After the political transformation, the Sejm passed an act, which reinstated the Warsaw city government (18 May 1990).

In 1995, the Warsaw Metro opened. It had been built since 1983. With the entry of Poland into the European Union in 2004, Warsaw is currently experiencing the biggest economic boom of its history.[39] An important stimulator of the economy is the European football championship, planned in Poland and Ukraine in 2012. 5 matches, including the opening match, are scheduled to take place in Warsaw.[40]

Historical images

-

Ossoliński Palace and Kazanowski Palace in 1656 -

View of Warsaw from Praga in 1770 -

View of Warsaw from the Royal Castle in 1773 -

Marszałkowska Street in 1912

See also

- Siege of Warsaw (1939)

- Siege (film)

- Warsaw concentration camp

- Warsaw Uprising

- Warsaw Pact

- List of presidents of Warsaw

- Warsaw pogrom (1881)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Template:En icon "Warsaw's history". www.e-warsaw.pl. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Paweł Giergoń. "Pomnik Stanisława Nałęcz hr. Małachowskiego". www.sztuka.net. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Template:Pl icon Dobrosław Kobielski (1984). Widoki dawnej Warszawy (Views of Old Warsaw). Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. ISBN 83-03-00702-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Template:En icon Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925339-0.

- ^ Dariusz Kaczmarczyk, Kościół Św. Anny, Warszawa 1984, s. 34.

- ^ Template:En icon Neal Ascheron. "The Struggles for Poland". www.halat.pl. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ a b Template:En icon "Baltic campaigns: AD 1700-1706". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ a b c d Template:Pl icon Historia Warszawy (History of Warsaw). Warsaw. 2004. ISBN 83-89632-04-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Template:En icon "Royal Castle during the Saxons". Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Template:En icon "The Bygone Warsaw". polbox.pl. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ a b Template:En icon Maria Witt (September 15 and October 15, 2005). "The Zaluski Collection in Warsaw". The Strange Life of One of the Greatest European Libraries of the Eighteenth Century. FYI France. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Template:En icon Lech Chmielewski. "In the House under the Sign of the Kings". Welcome to Warsaw. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ Template:En icon Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Warsaw. 1977. ISBN 0-8247-2020-2. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 699. ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- ^ Madariaga: Catherine the Great: a Short History (Yale) p.175

- ^ John T. Alexander, Catherine the Great: Life and Legend, Oxford University Press US, 1999, ISBN 0-19-506162-4, Google Print, p.317

- ^ "According to one Russian estimate 20,000 people had been killed in the space of a few hours" (Adam Zamoyski: The Last King of Poland, London, 1992 p.429)

- ^ Template:Pl icon[1]

- ^ Template:En icon Richard S. Wortman (2000). Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02947-4. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:Fr Zbigniew Naliwajek « Romain Rolland et la littérature polonaise », Revue de littérature comparée 3/2003 (n°307), p. 325-338.

- ^ a b Template:En icon Augustin P. O'Brien (1864). Petersburg and Warsaw: Scenes Witnessed During a Residence in Poland and Russia in 1863-4. R. Bentley. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Robert Blobaum, Feliks Dzierzynski and the SDKPIL a study of the origins of Polish Communism, page 57

- ^ Template:En icon "Poland, History » Poland in the 20th century » From the Treaty of Versailles to the Treaty of Riga". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Template:En icon Zdzisław G. Kowalski. "Documents of the Battle of Warsaw 1920". Memory of the World. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ "Vistula River Victory". www.electronicmuseum.ca. Archived from the original on 12-06-2008. Retrieved 14-07-2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|archivedate=(help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Andrzej Garlicki (1979). Przewrót majowy. Warszawa: Czytelnik. p. 388. ISBN 83-07-00069-6.

- ^ Template:Pl icon "Błotne kąpiele samorządu Warszawy". Robotnik. 8 September 1934. p. 2.

- ^ a b Template:En icon Anthony M. Tung (2001). Preserving the world's great cities: the destruction and renewal of the historic metropolis. Clarkson Potter. p. 77.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:En icon "Battle for Warsaw". www.open2.net. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ Template:En icon "Warsaw". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ a b c Template:En icon "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ Template:En icon "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising". www.aish.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Template:En icon "Warsaw Uprising of 1944". www.warsawuprising.com. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Template:En icon "Warsaw Uprising of 1944". www.warsawuprising.com. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Marek Getter (2004). Straty ludzkie i materialne w powstaniu warszawskim (Personal and material looses in the Warsaw Uprising). Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej (Institute of National Remembrance). ISBN 83-03-00702-5.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Zespół Doradców Prezydenta miasta stołecznego Warszawy (A Team of Advisers of the President of the Capital City of Warsaw) (2004). "Straty wojenne Warszawy 1939-1945. Raport (Warsaw's war looses 1939-1945. Report)" (PDF). www.um.warszawa.pl. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ Template:En icon "Historic Centre of Warsaw". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ a b c Template:En icon "Pope in Warsaw". www.destinationwarsaw.com. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ Template:En icon "Attracting foreign investments". www.polandtrade.com.hk. The Warsaw Voice. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ Template:En icon "The National Stadium in Warsaw". www.poland2012.net. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

External links

- Historical Museum of Warsaw

- History of Warsaw

- Warsaw 1935 - virtual reconstruction of pre-War World II Warsaw

- Architecture of pre-war Warsaw

- The Virtual Jewish History Tour, Warsaw

- Jews in Warsaw (from Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971)