Timeline of tuberous sclerosis

The timeline of tuberous sclerosis discovery and research stretches over less than 200 years. Tuberous sclerosis (TSC) is a rare, multi-system genetic disease that causes benign tumours to grow in the brain and on other vital organs such as the kidneys, heart, eyes, lungs, and skin. A combination of symptoms may include seizures, developmental delay, behavioural problems, skin abnormalities, lung and kidney disease. TSC is caused by mutations on either of two genes, TSC1 and TSC2, which encode for the proteins hamartin and tuberin respectively. These proteins act as tumour growth suppressors, agents that regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.[1] Originally regarded as a rare pathological curiosity, it is now an important focus of research into tumour formation and suppression. There are four chapters to the story of tuberous sclerosis:[2]

- The original descriptions and identification of an independent disease.

- The discovery of the various manifestations of the disease.

- Significant diagnostic improvements are made:

- a. New cranial imaging techniques allow the brain and other organs to be examined in detail.

- b. Identification of the genes involved enabled genetic testing.

- The beginnings of therapeutic treatments, based on a molecular understanding of the illness.

The earliest work on TSC came from individual, notable physicians, working in the great teaching hospitals of nineteenth century Europe. They have been awarded with eponyms such as "Bourneville's disease"[3] and "Pringle's adenoma sebaceum".[4] In comparison, much recent research involves large international teams.

Nineteenth century

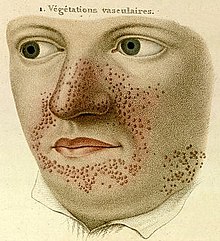

1835 The French dermatologist Pierre François Olive Rayer published an atlas of skin diseases. It contains 22 large coloured plates with 400 figures presented in a systematic order. On page 20, fig. 1 is a drawing that is regarded as the earliest description of tuberous sclerosis.[5] Entitled "végétations vasculaires", Rayer notes these are "small vascular, of papulous appearance, widespread growths distributed on the nose and around the mouth".[6] No mention is made of any medical condition associated with the skin disorder.

1850 English dermatologists Thomas Addison and William Gull described, in Guy's Hospital Reports, the case of a 4-year-old girl with a "peculiar eruption extending across the nose and slightly affecting both cheeks", which they called "vitiligoidea tuberosa".[7]

1862 The German physician Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen, who was working as an assistant to Rudolf Virchow in the Institute for Pathological Anatomy in Berlin,[8] presented a case to the city's Obstetrical Society. The heart of an infant who "died after taking a few breaths" had several tumours. He called these tumours "myomata", one of which was "size of a pigeon's egg".[7] He also noted the brain had a "a great number of scleroses".[5] These were almost certainly the cardiac rhabdomyomas and cortical tubers of tuberous sclerosis. He failed to recognise a distinct disease, regarding it as a pathological-anatomical curiosity.[9] Von Recklinghausen's name would instead become associated with neurofibromatosis after a classic paper in 1881.[8]

1864 German pathologist Rudolf Virchow published a three-volume work on tumours that described a child with cerebral tuberous sclerosis and rhabdomyoma of the heart. There is the first hint that this may be an inherited disease: the child's sister had died of a cerebral tumour.[10]

1880 The French neurologist Désiré-Magloire Bourneville had a chance encounter with the disease that would bear his name. He was working as an unofficial assistant to Jean Martin Charcot at La Salpêtrière.[9] While substituting for his teacher, Lois J.F. Delasiauve,[11] he attended to Marie, a 15-year-old girl with psychomotor retardation, epilepsy and a "confluent vascular-papulous eruption of the nose, the cheeks and forehead". She had a history of seizures since infancy and was taken to the children's hospital aged 3 and declared a hopeless case. She had learning difficulties and could neither walk nor talk. While under Bourneville's care, Marie had an ever increasing number of seizures, which came in clusters. She was treated with quinquina, bromide of camphor, amyl nitrite, and the application of leeches behind the ears. On 1879-05-07 Marie died in her hospital bed. The post-mortem examination disclosed hard, dense tubers in the cerebral convolutions, which Bourneville named Sclérose tubéreuse des circonvolution cérébrales. He concluded they were the source (focus) of her seizures. In addition, whitish hard masses, one "the size of a walnut", were found in both kidneys.[12]

1881 The German physician Hartdegen described the case of 2-day-old baby who died in status epilepticus. Post-mortem examination revealed small tumours in the lateral ventricles of the brain and areas of cortical sclerosis, which he called "glioma gangliocellulare cerebri congenitum".[13][14]

1881 Bourneville and Édouard Brissaud examined a 4-year-old boy at La Bicétre. As before, this patient had cortical tubers, epilepsy and learning difficulties. In addition he had a heart murmur and, on post-mortem examination, had tiny hard tumours in the ventricle walls in the brain (subependymal nodules) and small tumours in the kidneys (angiomyolipomas).[15]

1885 French physicians Félix Balzer and Pierre Eugène Ménétrier reported a case of "adénomes sébacés de la face et du cuir" (adenoma of the sebaceous glands of the face and scalp).[16] The term has since proved to be incorrect as they are neither adenoma nor derived from sebaceous glands. The papular rash is now known as facial angiofibroma.[17]

1885 French dermatologists François Henri Hallopeau and Émile Leredde published a case of adenoma sebaceum that was of a hard and fibrous nature. They first described the shagreen plaques and later would note an association between the facial rash and epilepsy.[18][7]

1890 The Scottish dermatologist John James Pringle, working in London, described a 25-year-old woman with subnormal intelligence, rough lesions on the arms and legs, and the papular facial rash that would bear his name. Pringle brought attention to five previous reports, two of which were unpublished.[19] Pringle's adenoma sebaceum would become a common eponym for the facial rash.

Early twentieth century

1901 GB Pellizzi studied the pathology of the cerebral lesions. He noted their dysplastic nature, the cortical heterotopia and defective myelination. Pellizzi classified the tubers into type 1 (smooth surface) and type 2 (with central depressions).[20][21]

1903 Richard Kothe described periungual fibromas, which were later rediscovered by Johannes Koenen in 1932 (known as Koenen's tumours).[22]

1908 The German paediatric neurologist Heinrich Vogt established the diagnostic criteria, firmly associating the facial rash with the neurological consequences of the cortical tubers.[23][24] Vogt's triad of epilepsy, idiocy, and adenoma sebaceum held for 60 years until research by Manuel Gómez discovered that fewer than a third of patients with TSC had all three symptoms.[5]

1910 J. Kirpicznick was first to recognise that TSC was a genetic condition. He described cases of identical and fraternal twins and also one family with three successive generations affected.[25]

1911 Edward Sherlock, barrister-at-law and lecturer in biology, reported nine cases in his book on the "feeble-minded". He coined the term epiloia, a portmanteau of epilepsy and anoia (mindless).[26] The word is no longer widely used as a synonym for TSC. The geneticist Robert James Gorlin suggested in 1981 that it could be a useful acronymn for epilepsy, low intelligence, and adenoma sebaceum.[27]

1913 H. Berg is credited with first stating that TSC was a hereditary disorder, noting its transmission through two or three generations.[28]

1914 P. Schuster described a patient with adenoma sebaceum and epilepsy but of normal intelligence.[7] This reduced phenotypic expression is called a forme fruste.[29]

1918 The French physician René Lutembacher published the first report of cystic lung disease in a patient with TSC. The 36-year-old woman died from bilateral pneumothoraces. Lutembacher believed the cysts and nodules to be metastases from a renal fibrosarcoma. This complication, which only affects women, is now known as lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).[30][31]

1920 Dutch ophthalmologist Jan van der Hoeve described the retinal hamartomas (phakoma). He grouped both TSC and neurofibromatosis together as "phakomatoses" (later called neurocutaneous syndromes).[32]

1924 H. Marcus noted that characteristic features of TSC such as intracranial calcifications were visible on x-ray.[33]

Mid-twentieth century

1932 MacDonald Critchley and Charles J.C. Earl studied 29 patients with TSC who were in mental institutions. They described behaviour — unusual hand movements, bizarre attitudes and repetitive movements (stereotypies) — that today would be recognised as autistic. However it would be 11 years before Leo Kanner suggested the term "autism". They also noticed the associated white spots (hypomelanic macules).[34]

1934 N.J. Berkwitz and L.G. Rigler showed it was possible to diagnose tuberous sclerosis using pneumoencephalography to highlight non-calcified subependymal nodules. These resembed "the wax drippings of a burning candle" on the lateral ventricles.[35]

1954 Reidar Eker bred a line of Wistar rats predisposed to renal adenomas. The Eker rat became an important model of dominantly inherited cancer.[36]

1966 Phanor Perot and Bryce Weir pioneered surgical intervention for epilepsy in TSC. Of the seven patients who underwent cortical tuber resection, two became seizure-free. Prior to this, only four patients had ever been surgically treated for epilepsy in TSC. [37]

1967 J.C. Lagos and Manuel Rodríguez Gómez reviewed 71 TSC cases and found that 38% of patients have normal intelligence.[38][13]

1971 Alfred Knudson developed his "two hit" hypothesis to explain the formation of retinoblastoma in both children and adults. The children had a congenital germline mutation which was combined with an early lifetime somatic mutation to cause a tumour. This model applies to many conditions involving tumour suppressor genes such as TSC.[39] In the 1980s, Knudson's studies on the Eker rat strengthened this hypothesis.[40]

1975 Giuseppe Pampiglione and E. Pugh, in a letter to The Lancet, noted that up to 69% of patients presented with infantile spasms.[41]

1975 Riemann used kidney ultrasound in the case of a 35-year-old woman with chronic renal failure and TSC.[42]

Late twentieth century

1976 Cranial computed tomography (CT, invented 1972) proved to be an excellent tool for diagnosing cerebral neoplasms in children, including those found in tuberous sclerosis.[43]

1979 Manuel Gómez published a monograph: "Tuberous Sclerosis" that remained the standard textbook for three editions over two decades. The book described the full clinical spectrum of TSC for the first time and established a new set of diagnostic criteria to replace the Vogt triad.[44][13]

1982 Kenneth Arndt successfully treated facial angiofibroma with an argon laser.[45]

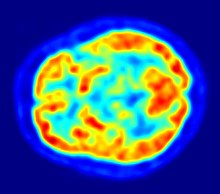

1983 Positron emission tomography (PET, invented 1981) was compared to electroencephalography (EEG) and CT. It was found to be capable of locating epileptogenic cortical tubers that would otherwise have been missed.[46]

1984 The cluster of infantile spasms in TSC is discovered to be preceded by a focal EEG discharge.[47]

1985 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, invented 1980) was first used in TSC to identify affected regions in the brain of a girl with tuberous sclerosis.[48]

1987 MR was judged superior to CT imaging for both sensitivity and specificity. In a study of 15 patients, it identified subependymal nodules projecting into the lateral ventricles in 12 patients, distortion of the normal cortical architecture in 10 patients (corresponding to cortical tubers), dilated ventricles in 5 patients and distinguished a known astrocytoma from benign subependymal nodules in 1 patient.[49]

1987 MR imaging was found to be capable of predicting the clinical severity of the disease (epilepsy and developmental delay). A study of 25 patients found a correlation with the number of cortical tubers identified. In contrast, CT was not a useful predictor, but was superior at identifying calcified lesions.[50]

1987 Linkage analysis on 19 families with TSC located a probable gene on chromosome 9.[51]

1988 Cortical tubers found on MR imaging corresponded exactly to the location of persistent EEG foci, in a study of six children with TSC. In particular, frontal cortical tubers were associated with more intractable seizures.[52]

1990 Vigabatrin was found to be a highly effective antiepileptic treatment for infantile spasms, particularly in children with TSC.[53] Following the discovery in 1997 of severe persistent visual field constriction as a possible side-effect, vigabatrin monotherapy is now largely restricted to this patient group.[54]

1992 Linkage analysis located a second gene to chromosome 16p13.3, close to the polycystic kidney disease type 1 (PKD1) gene.[55]

1993 The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium announced the cloning of TSC2; its product is called tuberin.[56]

1994 The Eker rat is discovered to be an animal model for tuberous sclerosis; it has a mutation in the rat-equivalent of the TSC2 gene.[57]

1995 MRI with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences was reported to be significantly better than standard T2-weighted images at highlighting small tubers, especially subcortical ones.[58][59]

1997 The TSC1 Consortium announced the cloning of TSC1; its product is called hamartin.[60]

1997 The PKD1 gene, which leads to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), and the TSC2 gene were discovered to be adjacent on chromosome 16p13.3. A team based at the Institute of Medical Genetics in Wales studied 27 unrelated patients with TSC and renal cystic disease. They concluded that serious renal disease in those with TSC is usually due to contiguous gene deletions of TSC2 and PKD1. They also noted that the disease was different (earlier and more severe) than ADPKD and that patients with TSC1 did not suffer significant cystic disease.[61]

1997 Patrick Bolton and Paul Griffiths examined 18 patients with TSC, half of whom had some form of autism. They found a strong association between tubers in the temporal lobes and the patients with autism.[62]

1998 The Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference issued revised diagnosic criteria, which is the current standard.[63]

1998 An Italian team used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to study three patients with TSC and partial epilepsy. Combined with MRI, they were able to study the association between tuberous areas of the brain, neuronal malfunctioning and epileptogenic areas.[64] Later studies would confirm that MEG is superior to EEG in identifying the eliptogenic tuber, which may be a candidate for surgical resection.[65]

Twenty-first century

2001 A multi-centre cohort of 224 patients were examined for mutations and disease severity. Those with TSC2 were less severely affected than those with TSC1. They had fewer seizures and less mental impairment. Some symptoms of TSC were rare or absent in those with TSC1. A conclusion is that "both germline and somatic mutations appear to be less common in TSC1 than in TSC2".[66]

2002 A team from the Epilepsy Centre Bethel at Bielefeld in Germany reported on 8 patients with TSC who underwent epilepsy surgery to remove the leading epileptogenic tuber. Seizure outcome was good in all patients, with two becoming seizure free. The authors encouraged surgery at an early age in this patient group.[67]

2002 Several research groups investigated how the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products (tuberin and hamartin) work together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signalling. This important pathway regulates cell proliferation and tumour suppression.[68]

2002 Treatment with rapamycin (sirolimus) is found to shrink tumours in the Eker rat (TSC2)[69] and mouse (TSC1)[70] models of tuberous sclerosis.

2006 Small trials show promising results in the use of rapamycin to shrink angiomyolipoma[71] and astrocytomas.[72] Several larger multicentre clinical trials are underway. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)[73] and kidney angiomyolipoma (AML)[74] are treated with rapamycin. Giant cell atrocytomas are treated with the rapamycin derivative everolimus.[75]

Notes

- ^ "Tuberous Sclerosis Fact Sheet". NINDS. 2006-04-11. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rott (2005), page 2 - Introduction.

- ^ Enersen, Ole Daniel. "Désiré-Magloire Bourneville". Who Named It?. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ Enersen, Ole Daniel. "John James Pringle". Who Named It?. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b c Curatolo (2003), chapter: "Hisorical Background".

- ^ Rayer, Pierre François (1835). Traité des maladies de la peau / atlas (in French). Paris: J.B. Baillière. p. 20. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- ^ a b c d Jay V (2004). "Historical contributions to pediatric pathology: Tuberous Sclerosis" (PDF). Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 2 (2): 197–198. PMID 9949228.

- ^ a b Enersen, Ole Daniel. "Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen". Who Named It?. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ a b Jansen F, van Nieuwenhuizen O, van Huffelen A (2004). "Tuberous sclerosis complex and its founders". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 75 (5): 770. PMID 15090576.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Virchow R (1863–7). Die Krankhaften Geschwülste. Vol II. Berlin: August Hirschwald. p. 148.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) as cited in Acierno (1994) - ^ Wilkins, Robert H (ed); Brody, Irwin A (ed) (1997). "XXXI Tuberous Sclerosis". Neurological Classics. American Association of Neurological Surgeons. pp. 149–52. ISBN 1879284499.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (contains an abridged translation of Bourneville's 1880 paper) - ^ Bourneville D (1880). "Sclérose tubéreuse des circonvolution cérébrales: Idiotie et épilepsie hemiplégique". Archives de neurologie, Paris. 1: 81–9l. Retrieved 2006-12-10. (online copy of the original French paper)

- ^ a b c Sancak, Özgür (2005). Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Mutations, Functions and Phenotypes. Stichting Tubereuze Sclerose Nederland. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9090201939.

- ^ Hartdegen A (1881). "Ein Fall von multipler Verhärtung des Grosshirns nebst histologisch eigenartigen harten Geschwülsten der Seitenventrikel ("Glioma gangliocellulare") bei einem Neugeborenen". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (1): 117–31. doi:10.1007/BF02054825.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Bourneville D, Brissaud É (1881). "Encéphalite ou sclérose tubéreuse des circonvolutions cérébrales". Archives de neurologie, Paris. 1: 390–412. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Balzer F, Ménétrier P (1885). "Étude sur un cas d'adénomes sébacés de la face et du cuir". Archives de Physiologie normale et pathologique (série III). 6: 564–76. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Sanchez N, Wick M, Perry H (1981). "Adenoma sebaceum of Pringle: a clinicopathologic review, with a discussion of related pathologic entities". Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 8 (6): 395–403. PMID 6278000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hallopeau F (1885). "Sur un cas d'adenomes sébacés à forme sclereuse". Ann Dermatol Syph. 6: 473–9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Pringle, JJ (1890). "A case of congenital adenoma sebaceum". British Journal of Dermatology, Oxford. 2: 1–14. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Pellizzi GB (1901). "Contributo allo studio dell'idiozia: rivisita sperimentale di freniatria e medicina legale delle alienazioni mentali". Riv Sper Freniat. 27: 265–269. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Braffman BH, Bilaniuk LT, Naidich TP, Altman NR, Post MJ, Quencer RM, Zimmerman RA, Brody BA (1992). "MR imaging of tuberous sclerosis: pathogenesis of this phakomatosis, use of gadopentetate dimeglumine, and literature review" (PDF). Radiology. 183 (1): 227–38. PMID 1549677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kothe R (1903). "Zur Lehre der Talgdrüsengeschwülste". Archives of Dermatology and Syphilis (in German). 68: 273–278. as cited in Rott (2005)

- ^ Enersen, Ole Daniel. "Heinrich Vogt". Who Named It?. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Vogt H (1908). "Zur Diagnostik der tuberösen Sklerose". Zeitschrift für die Erforschung und Behandlung des jugendlichen Schwachsinns auf wissenschaftlicher Grundlage, Jena. 2: 1–16. as cited in Curatolo (2003 and fully cited by Who Named It?)

- ^ Kirpicznik J (1910). "Ein Fall von Tuberoser Sklerose und gleichzeitigen multiplen Nierengeschwùlsten". Virchow's Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin. 202 (3): 258. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Sherlock, Edward Birchall (1911). The Feeble-minded, A Guide to Study and Practice. Macmillan & Co. as cited in Acierno (1994)

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 191100

- ^ Berg H (1913). "Vererbung der tuberösen Sklerose durch zwei bzw. drei Generationen". Z ges Neurol Psychiatr (in German). 19: 528–539. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Schuster P (1914). "Beiträge zur Klinik der tuberösen Sklerose des Gehirns". Dtsch Z Nervenheilk (in German). 50: 96–133. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Lutembacher R (1918). "Dysembryomes métatypique des reins. Carcinose submiliaire aigue du poumon avec emphysème généralisé et double pneumothorax". Ann Med (in French). 5: 435–450. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Abbott GF, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Frazier AA, Franks TJ, Pugatch RD, Galvin JR. (2005). "From the archives of the AFIP: lymphangioleiomyomatosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation" (PDF). Radiographics. 25 (3): 803–28. PMID 15888627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van der Hoeve J (1920). "Eye symptoms in tuberous sclerosis of the brain". Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 40: 329–334. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Marcus H (1924). Svenska Làk Sallsk Forth. as cited by Dickerson WW (1945). "Characteristic roentgenographic changes associated with tuberous sclerosis". Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry: 199–204.

{{cite journal}}: Text "volume 53" ignored (help) as cited in Curatolo (2003) and Gómez (1995) - ^ Critchley M, Earl CJC (1932). "Tuberose sclerosis and allied conditions". Brain. 55: 311–346. doi:10.1093/brain/55.3.311. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Berkwitz NJ, Rigler LG (1934). "Tuberous sclerosis diagnosed with cerebral pneumography". Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 35: 833–8. as cited in Gómez (1995)

- ^ Eker R (1954). "Familial renal adenomas in Wistar rats; a preliminary report". Acta Pathologica et Microbiologica Scandinavica. 34 (6): 554–62. PMID 13206757. as cited in Yeung (1994)

- ^ Perot P, Weir B, Rasmussen T (1966). "Tuberous sclerosis. Surgical therapy for seizures". Archives of Neurology. 15 (5): 498–506. PMID 5955139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Bebin EM, Kelly PJ, Gomez MR (1993). "Surgical treatment for epilepsy in cerebral tuberous sclerosis". Epilepsia. 34 (4): 651–7. PMID 8330575.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lagos JC, Gómez MR (1967). "Tuberous sclerosis: reappraisal of a clinical entity". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 42 (1): 26–49. PMID 5297238. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Knudson AG (1971). "Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 68 (4): 820–3. PMID 5279523. as cited in Rott (2005)

- ^ Yeung R (2004). "Lessons from the Eker rat model: from cage to bedside". Current Molecular Medicine. 4 (8): 799–806. PMID 15579026.

- ^ Pampiglione G, Pugh E (1975). "Letter: Infantile spasms and subsequent appearance of tuberous sclerosis syndrome". Lancet. 2 (7943): 1046. PMID 53537. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Riemann JF, Mörl M, Rott HD (1975). "Chronische Niereninsuffizienz bei Morbus Bourneville-Pringle (Chronic renal failure in bourneville-pringle's disease)". Medizinische Klinik (in German). 70 (26): 1128–32. PMID 1223616.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Berger PE, Kirks DR, Gilday DL, Fitz CR, Harwood-Nash DC (1976). "Computed tomography in infants and children: intracranial neoplasms". American Journal of Roentgenology. 127 (1): 129–37. PMID 180824.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Gómez, Manuel R (1979). Tuberous Sclerosis (1st Ed ed.). New York: Raven Press. ISBN 0890043132.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)as cited in Özgür (2005) - ^ Arndt KA (1982). "Adenoma sebaceum: successful treatment with the argon laser". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 70: 91–93. PMID 7089113. as cited in Rott (2005)

- ^ Szelies B, Herholz K, Heiss W; et al. (1983). "Hypometabolic cortical lesions in tuberous sclerosis with epilepsy: demonstration by positron emission tomography". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 7 (6): 946–53. PMID 6415136.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Dulac O, Lemaitre A, Plouin P (1984). "The Bourneville syndrome: clinical and EEG features of epilepsy in the first year of life". Boll Lega Ital Epil. 45/46: 39–42.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Kandt RS, Gebarski SS, Goetting MG (1985). "Tuberous sclerosis with cardiogenic cerebral embolism: magnetic resonance imaging". Neurology. 35 (8): 1223–5. PMID 4022361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ McMurdo SK Jr, Moore SG; et al. (1987). "MR imaging of intracranial tuberous sclerosis". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 148 (4): 791–6. PMID 3493666.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Roach ES, Williams DP, Laster DW (1987). "Magnetic resonance imaging in tuberous sclerosis". Arch Neurol. 44 (3): 301–3. PMID 3827681.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Fryer AE, Chalmers A, Connor JM; et al. (1987). "Evidence that the gene for tuberous sclerosis is on chromosome 9". Lancet. 1 (8534): 659–61. PMID 2882085.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Curatolo P, Cusmai R (1988). "Imagerie par résonance magnétique nucléaire dans la maladie de Bourneville: relation avec les données électroencéphalographiques (Magnetic resonance imaging in the Bourneville syndrome: relations with EEG)". Neurophysiologie clinique (in French). 18 (5): 459–67. PMID 3185465. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Chiron C, Dulac O, Luna D; et al. (1990). "Vigabatrin in infantile spasms". Lancet. 335 (8685): 363–4. PMID 1967808.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Vigabatrin Paediatric Advisory Group (2000). "Guideline for prescribing vigabatrin in children has been revised". BMJ. 320 (7246): 1404–5. PMID 10858057.

- ^ Kandt RS, Haines JL, Smith M; et al. (1992). "Linkage of an important gene locus for tuberous sclerosis to a chromosome 16 marker for polycystic kidney disease". Nature Genetics. 2 (1): 37–41. PMID 1303246.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium (1993). "Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16". Cell. 75 (7): 1305–15. PMID 8269512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Yeung R, Xiao G, Jin F, et all (1994). "Predisposition to renal carcinoma in the Eker rat is determined by germ-line mutation of the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91 (24): 11413–6. PMID 7972075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maeda M, Tartaro A, Matsuda T, Ishii Y (1995). "Cortical and subcortical tubers in tuberous sclerosis and FLAIR sequence". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 19 (4): 660–1. PMID 7622707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takanashi J, Sugita K, Fujii K, Niimi H (1995). "MR evaluation of tuberous sclerosis: increased sensitivity with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and relation to severity of seizures and mental retardation". AJNR American Journal of Neuroradiology. 16 (9): 1923–8. PMID 8693996.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C; et al. (1997). "Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34". Science. 277 (5327): 805–8. PMID 9242607.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Curatolo (2003) - ^ Sampson JR, Maheshwar MM, Aspinwall R; et al. (1997). "Renal cystic disease in tuberous sclerosis: role of the polycystic kidney disease 1 gene". American Journal of Human Genetics. 61 (4): 843–51. PMID 9382094.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Bolton PF, Griffiths PD (1997). "Association of tuberous sclerosis of temporal lobes with autism and atypical autism". Lancet. 349 (9049): 392–5. PMID 9033466. as cited in Curatolo (2003)

- ^ Roach ES, Gómez MR, Northrup H (1998). "Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria". Journal of Child Neurology. 13 (12): 624–8. PMID 9881533.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Peresson M, Lopez L, Narici L, Curatolo P (1998). "Magnetic source imaging and reactivity to rhythmical stimulation in tuberous sclerosis". Brain Dev. 20 (7): 512–8. PMID 9840671.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Jansen F, Huiskamp G, van Huffelen A, Bourez-Swart M, Boere E, Gebbink T, Vincken K, van Nieuwenhuizen O (2006). "Identification of the epileptogenic tuber in patients with tuberous sclerosis: a comparison of high-resolution EEG and MEG". Epilepsia. 47 (1): 108–14. PMID 16417538.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN; et al. (2001). "Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs". The American Jounal of Human Genetics. 68 (1): 64–80. PMID 11112665.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karenfort M, Kruse B, Freitag H, Pannek H, Tuxhorn I (2002). "Epilepsy surgery outcome in children with focal epilepsy due to tuberous sclerosis complex". Neuropediatrics. 33 (5): 255–61. PMID 12536368.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) as cited in Rott (2005) - ^ Tee A, Fingar D, Manning B, Kwiatkowski D, Cantley L, Blenis J (2005-10-15). "Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99 (21): 13571–6. PMID 12271141.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kenerson H, Aicher L, True L, Yeung R (2002). "Activated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis complex renal tumors". Cancer Res. 62 (20): 5645–50. PMID 12384518.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kwiatkowski D, Zhang H, Bandura J; et al. (2002). "A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells". Hum Mol Genet. 11 (5): 525–34. PMID 11875047.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wienecke R, Fackler I, Linsenmaier U, Mayer K, Licht T, Kretzler M (2006). "Antitumoral activity of rapamycin in renal angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 48 (3): e27-9. PMID 16931204.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Franz DN, Leonard J, Tudor C; et al. (2006). "Rapamycin causes regression of astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex". Ann Neurol. 59 (3): 490–8. PMID 16453317.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Multicenter International Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Efficacy of Sirolimus Trial (The MILES Trial)". ClinicalTrials.gov (NIH). 2007-01-06. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Sirolimus in Treating Patients With Angiomyolipoma of the Kidney". ClinicalTrials.gov (NIH). 2006-11-21. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Everolimus (RAD001) Therapy of Giant Cell Astrocytoma in Patients With Tuberous Sclerosis Complex". ClinicalTrials.gov (NIH). 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Acierno, Louis J. (1994-02-15). The History of Cardiology. Taylor & Francis. p. 427. ISBN 1850703396.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Curatolo, Paolo (Editor) (2003). Tuberous Sclerosis Complex : From Basic Science to Clinical Phenotypes. MacKeith Press. ISBN 1-898683-39-5.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Gómez MR (1995). "History of the tuberous sclerosis complex". Brain & Development. 17 (suppl): 55–7.

- Rott HD, Mayer K, Walther B, Wienecke R (2005-03-27). "Zur Geschichte der Tuberösen Sklerose [The History of Tuberous Sclerosis]" (PDF) (in German). Tuberöse Sklerose Deutschland e.V. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)