Trần dynasty: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

| stat_pop2 = 4,500,000 |

| stat_pop2 = 4,500,000 |

||

| ref_pop2 = <ref>{{Harvnb|Đại Việt's Office of History|1993|pp=509.}}</ref> |

| ref_pop2 = <ref>{{Harvnb|Đại Việt's Office of History|1993|pp=509.}}</ref> |

||

---> |

|||

| footnotes = |

| footnotes = |

||

| today = [[Vietnam]]<br />[[China]]<br />[[Laos]] |

| today = [[Vietnam]]<br />[[China]]<br />[[Laos]] |

||

Revision as of 22:47, 23 April 2024

21°02′15″N 105°50′19″E / 21.03750°N 105.83861°E

{{Infobox country

| native_name = 大越國

Đại Việt Quốc

| conventional_long_name = Great Việt

| common_name = Trần dynasty

| status = Monarchy, Tributary state

| status_text = Internal imperial system within Chinese tributary[1][2]

(Song 1225–1258)

(Yuan 1258–1368)

(Ming 1368–1400)

| era = Postclassical Era

| government_type = Monarchy

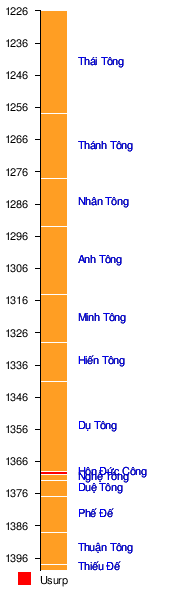

| year_start = 1225

| year_end = 1400

| event_start = Coronation of Trần Cảnh

| date_start = January 10

| event_end = Trần Thiếu Đế ceded the throne to Hồ Quý Ly

| date_end = March 23

| event1 = Regent of Trần Thừa and Trần Thủ Độ

| date_event1 = 1226

| event2 = Mongol invasions of Vietnam

| date_event2 = 1258, 1285 and 1287–88

| event3 = Coup overthrown of Dương Nhật Lễ

| date_event3 = 1370

| event_pre =

| date_pre = |

| p1 = Lý dynasty

| flag_p1 =

| p2 =

| p3 =

| p4 =

| s1 = Hồ dynasty

| flag_s1 =

| image_flag =

| flag_border =

| flag =

| flag_type =

| image_coat =

| symbol =

| symbol_type =

| image_map = VietNam(1226-1400).png

| image_map_caption =The expansion of Đại Việt. Trần dynasty from 1301 to 1337.

| image_map2 = TranDynasty1306.png

| image_map2_caption = The territory of Đại Việt in 1306 after the marriage of Vietnamese princess Huyền Trân and Cham king Jaya Simhavarman III. The province of Chau O (Cham: Vuyar) and Chau Ly (Cham: Ulik) was ceded to Đại Việt as dowry.

| capital = Thăng Long

(1225–1397)

Thanh Hóa (temp)

(1397–1400)

| national_motto =

| national_anthem =

| common_languages = Literary Chinese[3]

Vietnamese[3]

| religion = Buddhism (official), Taoism, Confucianism, Vietnamese folk religion

| currency = Copper-alloy cash coins

| title_leader = Emperor

| leader1 = Trần Thái Tông (first)

| year_leader1 = 1226–1258

| leader2 = Trần Thánh Tông

| year_leader2 = 1258–1278

| leader3 = Trần Nhân Tông

| year_leader3 = 1278–1293

| leader4 = Trần Anh Tông

| year_leader4 = 1293–1314

| leader5 = Trần Thiếu Đế (last)

| year_leader5 = 1398–1400

| title_deputy = Chancellor

| deputy1 = Trần Thủ Độ (first)

| year_deputy1 = 1225

| deputy3 = Trần Quốc Toản

| year_deputy3 = ?

| deputy4 = Trần Khánh Dư

| year_deputy4 = ?

| deputy5 = Trần Quang Khải

| year_deputy5 = ?

| deputy6 = Hồ Quý Ly (last)

| year_deputy6 = 1387| his brother's son Dương Nhật Lễ despite the fact that his appointee was not from the Trần clan.[4]

Like his predecessor Dụ Tông, Nhật Lễ neglected his administrative duties and concentrated only on drinking, theatre, and wandering. He even wanted to change his family name back to Dương. Such activities disappointed everyone in the imperial court. This prompted the Prime Minister Trần Nguyên Trác and his son Trần Nguyên Tiết to plot the assassination of Nhật Lễ, but their conspiracy was discovered by the Emperor and they were killed afterwards.

In the tenth lunar month of 1370, the Emperor's father-in-law, Trần Phủ, after receiving advice from several mandarins and members of the imperial family, decided to raise an army for the purpose of overthrowing Nhật Lễ. After one month, his plan succeeded and Trần Phủ became the new emperor of Đại Việt, ruling as Trần Nghệ Tông, while Nhật Lễ was downgraded to Duke of Hôn Đức (Hôn Đức Công) and was killed afterwards by an order of Nghệ Tông.[5][6][7][8]

After the death of Hôn Đức Công, his mother fled to Champa and begged King Chế Bồng Nga to attack Đại Việt. Taking advantage of his neighbour's lack of political stability, Chế Bồng Nga commanded troops and directly assaulted Thăng Long, the capital of Đại Việt. The Trần army could not withstand this attack and the Trần imperial court had to escape from Thăng Long, creating an opportunity for Chế Bồng Nga to violently loot the capital before withdrawing.[9]

In the twelfth lunar month of 1376 the Emperor Trần Duệ Tông decided to personally command a military campaign against Champa. Eventually, the campaign was ended by a disastrous defeat of Đại Việt's army at the Battle of Đồ Bàn, when the Emperor himself, along with many high-ranking mandarins and generals of the Trần dynasty, were killed by the Cham forces.[10] The successor of Duệ Tông, Trần Phế Đế, and the retired Emperor Nghệ Tông, were unable to drive back any invasion of Chế Bồng Nga in Đại Việt. As a result, Nghệ Tông even decided to hide money in Lạng Sơn, fearing that Chế Bồng Nga's troops might assault and destroy the imperial palace in Thăng Long.[11][12] In 1389 general Trần Khát Chân was appointed by Nghệ Tông to take charge of stopping Champa.[13] In the first lunar month of 1390, Trần Khát Chân had a decisive victory over Champa which resulted in the death of Chế Bồng Nga and stabilised situation in the southern part of Đại Việt.[14]

Downfall

During the reign of Trần Nghệ Tông, Hồ Quý Ly, an official who had two aunts entitled as consorts of Minh Tông,[15] was appointed to one of the highest positions in the imperial court. Despite his complicity in the death of the Emperor Duệ Tông, Hồ Quý Ly still had Nghệ Tông's confidence and came to hold more and more power at the imperial court.[16] Facing the unstoppable rise of Hồ Quý Ly in the court, the Emperor Trần Phế Đế plotted with minister Trần Ngạc to reduce Hồ Quý Ly's power, but Hồ Quý Ly pre-empted this plot by a defamation campaign against the Emperor which ultimately made Nghệ Tông decide to replace him by Trần Thuận Tông and downgrade Phế Đế to Prince Linh Đức in December 1388.[17][18] Trần Nghệ Tông died on the 15th day of the twelfth lunar month, 1394 at the age of 73 leaving the imperial court in the total control of Hồ Quý Ly.[19] He began to reform the administrative and examination systems of the Trần dynasty and eventually obliged Thuận Tông to change the capital from Thăng Long to Thanh Hóa in January 1397.[20]

On the full moon of the third lunar month, 1398, under pressure from Hồ Quý Ly, Thuận Tông, had to cede the throne to his three-year-old son Trần An, now Trần Thiếu Đế, and held the title Retired Emperor at the age of only 20.[21] Only one year after his resignation, Thuận Tông was killed on the orders of Hồ Quý Ly.[22] Hồ Quý Ly also authorised the execution of over 370 persons who opposed his dominance in the imperial court, including several prominent mandarins and the Emperor's relatives together with their families, such as Trần Khát Chân, Trần Hãng, Phạm Khả Vĩnh and Lương Nguyên Bưu.[23] The end of the Trần dynasty came on the 28th day of the second lunar month (Gregorian: March 23) 1400,[24] when Hồ Quý Ly decided to overthrow Thiếu Đế and established a new dynasty, the Hồ dynasty.[25] Being Hồ Quý Ly's own grandson, Thiếu Đế was downgraded to Prince Bảo Ninh instead of being killed like his father.[25][26] Hồ Quý Ly claimed descent from Duke Hu of Chen (Trần Hồ công, 陳胡公), whose Hồ clan originated in State of Chen (modern day Zhejiang, China[27][28]) around the 940s.

Later Trần

After the Ming dynasty conquered the Hồ dynasty in 1407, Prince Trần Ngỗi was declared emperor and led the Trần loyalists forces against the Chinese. His base was first centered in Ninh Bình Province. He defeated the Ming forces in 1408 but failed to retake Đông Quan (Hanoi). Due to internal purges, his offensive eventually failed and he had to retreat to Nghệ An. A new emperor, Trùng Quang Đế, was installed by the generals in 1409. The Later Trần held the southern provinces before being defeated by Ming forces in 1413.

Economy and society

To restore the country's economy, which had been heavily damaged during the turbulent time at the end of the Lý dynasty, Emperor Trần Thái Tông decided to reform the nation's system of taxation by introducing a new personal tax (thuế thân), which was levied on each person according to the area of cultivated land owned.[29] For example, a farmer who owned one or two mẫu, equal to 3,600 to 7,200 square metres (39,000 to 78,000 sq ft), had to pay one quan per year, while another with up to four mẫus had to pay two quan. Besides personal taxes, farmers were obliged to pay a land tax in measures of rice that was calculated by land classification. One historical book reveals that the Trần dynasty taxed everything from fish and fruits to betel.[30] Taxpayers were divided into three categories: minors (tiểu hoàng nam, from 18 to 20), adults (đại hoàng nam, from 20 to 60), and seniors (lão hạng, over 60).[29][30]

Manufactured items such as handicrafts, cotton, silk and brocades saw rapid development in this period. Some of these items were exported to China while silver, gold, tin and lead mining increased jewelry-making. State-minted copper coins were set up by the Tran authorities, so were weapons workshops, court attire workshops and utilities for bronze smelting. Education and literature were largely aided from improvements in the technology of printing and engraved wooden plates.[citation needed]

The shipbuilding industry expanded where large 100-oar junks were produced. Thang Long then became the state's commercial center with numerous markets established. A 13th-century Mongolian ambassador mentioned that markets were held twice a month, with "plenty of goods", and a market was situated every five miles on the state highway. Inns were also established by the state during the period.[citation needed]

During the reign of Trần Thánh Tông members of the Trần clan and imperial family were required by the Emperor to take full advantage of their land grants by hiring the poor to cultivate them.[31] [32] Đại Việt's cultivated land was annually ruined by river floods, so for a more stable agriculture, in 1244 Trần Thái Tông ordered his subordinates to construct a new system of levees along the Red River. Farmers who had to sacrifice their land for the diking were compensated with the value of the land. The Emperor also appointed a separate official to control the system.[30]

Towards the end of the Trần dynasty, Hồ Quý Ly held absolute power in the imperial court, and he began to carry out his ideas for reforming the economy of Đại Việt. The most significant change during this time was the replacement of copper coins with paper money in 1396. It was the first time in the history of Vietnam that paper money was used in trading.[33][34] The Emperor set up trading posts at the coastal town of Vân Đồn, where Chinese merchants from Guangdong and Fujian would move in to engage in commerce.[35] Ethnic Chinese are recorded in Tran and Ly dynasty records of officials.[36]

Culture

Literature

Trần literature is considered superior to Lý literature in both quality and quantity.[37] Initially, most members of the Trần clan were fishermen[38] without any depth of knowledge. For example, Trần Thủ Độ, the founder of the Trần dynasty, was described in Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư as a man of superficial learning.[39] However, after their usurpation of power from the Lý dynasty, Trần emperors and other princes and marquises always attached special importance to culture, especially literature.[40]

Two important schools of literature during the reign of the Trần dynasty were patriotic and Buddhist literature. To commemorate the victory of Đại Việt against the second Mongol invasion the grand chancellor Trần Quang Khải composed a poem, named Tụng giá hoàn kinh (Return to the capital), which was considered one of the finest examples of Vietnamese patriotic literature during the dynastic era.[41] Patriotism in Trần literature was also represented by the proclamation Hịch tướng sĩ (Call of Soldiers), written by general Trần Quốc Tuấn, which was the most popular work of the hịch (appeal, call) form in Vietnamese literature.[42]

Besides members of the Trần clan, there were several mandarins and scholars who were well known for patriotic works such as Trương Hán Siêu, an eminent author of the phú form,[40][43] or general Phạm Ngũ Lão with his famous poem Thuật hoài. As Buddhism was de facto the national religion of the Trần dynasty, there were many works of Trần literature that expressed the spirit of Buddhism and Zen, notably the works of the Emperor Trần Nhân Tông and other masters of Trúc Lâm School.[44]

`Besides the literature created by the upper classes, folk narratives of myths, legends, and ghost stories were also collected in Việt Điện U Linh Tập by Lý Tế Xuyên and Lĩnh Nam chích quái by Trần Thế Pháp. These two collections held great value not only for folk culture but also for the early history of Vietnam.[45]

Trần literature had a special role in the history of Vietnamese literature for its introduction and development of the Vietnamese language (Quốc ngữ) written in chữ nôm. Before the Trần dynasty, Vietnamese was only used in oral history or proverbs.[46] Under the rule of the Emperor Trần Nhân Tông, it was used for the first time as the second language in official scripts of the imperial court, besides Chinese.[44][better source needed]

It was Hàn Thuyên, an official of Nhân Tông, who began to compose his literary works in the Vietnamese language, with the earliest recorded poem written in chữ Nôm in 1282.[47] He was considered the pioneer who introduced chữ nôm in literature.[48] After Hàn Thuyên, chữ Nôm was progressively used by Trần scholars in composing Vietnamese literature, such as Chu Văn An with the collection Quốc ngữ thi tập (Collection of national language poems) or Hồ Quý Ly who wrote Quốc ngữ thi nghĩa to explain Shi Jing in the Vietnamese language.[49] The achievement of Vietnamese language literature during the Trần era was the essential basis for the development of this language and the subsequent literature of Vietnam.[44][better source needed]

Performing arts

The Trần dynasty was considered a golden age for music and culture.[50] Although it was still seen as a shameful pleasure at that time, theatre rapidly developed towards the end of the Trần dynasty with the role of Lý Nguyên Cát (Li Yuan Ki), a captured Chinese soldier who was granted a pardon for his talent in theatre. Lý Nguyên Cát imported many features of Chinese theatre (also see 话剧) in the performing arts of Đại Việt such as stories, costumes, roles, and acrobatics.[50] For that reason, Lý Nguyên Cát was traditionally considered the founder of the art of hát tuồng in Vietnam. However this is nowadays a challenged hypothesis because hát tuồng and Beijing opera differed in the way of using painted faces, costumes, or theatrical conventions.[51] The art of theatre was introduced to the imperial court by Trần Dụ Tông and eventually the emperor even decided to cede the throne to Dương Nhật Lễ, who was born to a couple of hát tuồng performers.[52]

To celebrate the victory over the 1288 Mongol invasion, Trần Quang Khải and Trần Nhật Duật created the Múa bài bông (dance of flowers) for a major three-day festival in Thăng Long. This dance has been handed down to the present and is still performed at local festivals in the northern region.[53]

Education and imperial examination system

Although Buddhism was considered the national religion of the Trần dynasty, Confucianist education began to spread across the country. The principal curricula during this time were the Four Books and Five Classics, and Northern history, which were at the beginning taught only at Buddhist pagodas and gradually brought to pupils in private classes organized by retired officials or Confucian scholars.[54]

The most famous teacher of the Trần dynasty was probably Chu Văn An, an official in the imperial court from the reign of Trần Minh Tông to the reign of Trần Dụ Tông, who also served as imperial professor of Crown Prince Trần Vượng.[55] During the reign of Trần Thánh Tông, the emperor also permitted his brother Trần Ích Tắc, a prince who was well known for his intelligence and knowledge, to open his own school at the prince's palace.[31] Several prominent mandarins of the future imperial court such as Mạc Đĩnh Chi and Bùi Phóng were trained at this school.[56]

The official school of the Trần dynasty, Quốc học viện, was established in June 1253 to teach the Four Books and Five Classics to imperial students (thái học sinh). The military school, Giảng võ đường, which focused on teaching about war and military manoeuvre, was opened in August of the same year.[30][57] Together with this military school, the first Temple of Military Men (Võ miếu) was built in Thăng Long to worship Jiang Ziya and other famous generals.[58]

Seven years after the establishment of the Trần dynasty, the Emperor Trần Thái Tông ordered the first imperial examination, in the second lunar month of 1232, for imperial students with the purpose of choosing the best scholars in Đại Việt for numerous high-ranking positions in the imperial court. Two of the top candidates in this examination were Trương Hanh and Lưu Diễm.[59] After another imperial examination in 1239, the Trần emperor began to establish the system of seven-year periodic examinations in order to select imperial students from all over the country.[54]

The most prestigious title of this examination was tam khôi (three first laureates), which was composed of three candidates who ranked first, second, and third in the examination with the names respectively of trạng nguyên (狀 元, exemplar of the state), bảng nhãn (榜 眼, eyes positioned alongside) and thám hoa (探 花, selective talent).[60] The first tam khôi of the Trần dynasty were trạng nguyên Nguyễn Hiền, who was only 12 at that time,[61] bảng nhãn Lê Văn Hưu who later became a imperial historian of the Trần dynasty,[62] and thám hoa Đặng Ma La.[63] In the 1256 examination, the Trần dynasty divided the title trạng nguyên into two categories, kinh trạng nguyên for candidates from northern provinces and trại trạng nguyên for those from two southern provinces: Thanh Hóa and Nghệ An,[64] so that students from those remote regions could have the motivation for the imperial examination. This separation was abolished in 1275 when the ruler decided that it was no longer necessary.[54]

In 1304, the Emperor Trần Anh Tông decided to standardize the examination by four different rounds in which candidates were eliminated step by step through tests of classical texts, Confucianist classics, imperial document redaction, and finally argument and planning.[65] This examining process was abandoned in 1396 by the Emperor Trần Thuận Tông under pressure from Hồ Quý Ly, who replaced the traditional examination with the new version as a part of his radical reforms of the social and administrative system.

Hồ Quý Ly regulated the imperial examination by a prefectural examination (thi hương) and a metropolitan examination (thi hội) following in the next year. The second-degree examination included four rounds: literary dissertation, literary composition, imperial document redaction, and eventually an essay which was personally evaluated by the Emperor.[66] For the lower-ranking officials, the emperor had another examination which tested writing and calculating, such as the examination in the sixth lunar month of 1261 during the reign of Trần Thánh Tông.[67]

During its 175 years of existence, the Trần dynasty carried out fourteen imperial examinations including ten official and four auxiliary contests. Many laureates from these examinations later became prominent officials in the imperial court or well-known scholars such as Lê Văn Hưu, author of the historical accounts Đại Việt sử ký,[62] Mạc Đĩnh Chi, renowned envoy of the Trần dynasty to the Yuan dynasty,[68] or Nguyễn Trung Ngạn, one of the most powerful officials during the reign of Trần Minh Tông.[68] Below is the complete list of examinations with the candidates who ranked first in each examination:[69]

| Year | Emperor | Ranked first | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1232 | Trần Thái Tông | Trương Hanh Lưu Diễm |

[59] |

| 1234 | Trần Thái Tông | Nguyễn Quan Quang | [69] |

| 1239 | Trần Thái Tông | Lưu Miễn Vương Giát |

[70] |

| 1247 | Trần Thái Tông | Nguyễn Hiền | Trạng nguyên[63] |

| 1256 | Trần Thái Tông | Trần Quốc Lặc | Kinh trạng nguyên[64] |

| Trương Xán | Trại trạng nguyên[64] | ||

| 1266 | Trần Thánh Tông | Trần Cố | Kinh trạng nguyên[32] |

| Bạch Liêu | Trại trạng nguyên[32] | ||

| 1272 | Trần Thánh Tông | Lý Đạo Tái | Trạng nguyên[69] |

| 1275 | Trần Thánh Tông | Đào Tiêu | Trạng nguyên[71] |

| 1304 | Trần Anh Tông | Mạc Đĩnh Chi | Trạng nguyên[65] |

| 1347 | Trần Dụ Tông | Đào Sư Tích | Trạng nguyên[72] |

Science and technology

There is evidence for the use of feng shui by Trần dynasty officials, such as in 1248 when Trần Thủ Độ ordered several feng shui masters to block many spots over the country for the purpose of protecting the newly founded Trần dynasty from its opponents.[73] Achievements in science during the Trần dynasty were not detailed in historical accounts, though a notable scientist named Đặng Lộ was mentioned several times in Đại Việt sử kí toàn thư. It was said that Đặng Lộ was appointed by Retired Emperor Minh Tông to the position of national inspector (liêm phóng sứ)[74] but he was noted for his invention called lung linh nghi, which was a type of armillary sphere for astronomic measurement.[75] From the result in observation, Đặng Lộ successfully persuaded the emperor to modify the calendar in 1339 for a better fit with the agricultural seasons in Đại Việt.[76][77] Marquis Trần Nguyên Đán, a superior of Đặng Lộ in the imperial court, was also an expert in calendar calculation.[78]

Gunpowder

Near the end of the Trần dynasty the technology of gunpowder appeared in the historical records of Đại Việt. It was responsible for the death of the King of Champa, Chế Bồng Nga, after general Trần Khát Chân fired a cannon from his battleship in January 1390.[14] According to the NUS researcher Sun Laichen, the Trần dynasty acquired gunpowder technology from China and effectively used it to change the balance of power between Đại Việt and Champa in favour of Đại Việt.[79] As a result of this Sun reasoned that the need for copper for manufacturing firearms was probably another reason for the order of Hồ Quý Ly to change from copper coins to paper money in 1396.[80]

The people of the Trần dynasty and the later Hồ dynasty continued to improve their firearms using gunpowder. This resulted in weapons of superior quality to their Chinese counterparts. These were acquired by the Ming dynasty in their invasion of Đại Việt.[81]

Medicine

During the rule of the Trần dynasty, medicine had a better chance to develop because of a more significant role of Confucianism in society.[82][83] In 1261,[67] the emperor issued an order to establish the Institute of Imperial Physicians (Thái y viện) which managed medicine in Đại Việt, carrying out the examination for new physicians and treating people during disease epidemics.[84] In 1265 the institute distributed a pill named Hồng ngọc sương to the poor, which they considered able to cure many diseases.[85] Besides the traditional Northern herbs (thuốc Bắc), Trần physicians also began to cultivate and gather various regional medicinal herbs (thuốc Nam) for treating both civilians and soldiers. During the reign of Trần Minh Tông the head of the Institute of Imperial Physicians Phạm Công Bân was widely known for his medical ethics, treating patients regardless of their descent with his own medicine made from regional herbs;[84][86] it was said that Phạm Công Bân gathered his remedies in a medical book named Thái y dịch bệnh (Diseases by the Imperial Physician).[87]

The monk Phạm Công Bân, also known as Tuệ Tĩnh, who was a famous physician in Vietnamese history, was called the "Father of the Southern Medicine" for creating the basis of Vietnamese traditional medicine with his works Hồng nghĩa giác tư y thư and Nam dược thần hiệu.[88] Nam dược thần hiệu was a collection of 499 manuscripts about local herbs and ten branches of treatment with 3932 prescriptions to cure 184 type of diseases while Hồng nghĩa giác tư y thư provided people with many simple, easy-to-prepare medicines that produced effective results.[88][89]

Gallery

-

Bình Sơn pagoda of Vĩnh Khánh Temple, Trần dynasty, Tam Sơn town, Lô river commune, Vĩnh Phúc province.

-

Pagoda of the Phổ Minh Temple

-

Wooden gate of Phổ Minh Temple

-

Carved wooden doors from the Phổ Minh Temple, Nam Định province, northern Vietnam (13th–14th century)

-

Terracotta Tower

-

Phoenix head. Terracotta, Trần-Hồ dynasty, 14th–15th century. Architectural decoration. National Museum of Vietnamese History, Hanoi.

-

Lion figure. Terracotta, Trần-Hồ dynasty, 14th–15th century. Nghệ An province, central Vietnam. Architectural decoration. National Museum of Vietnamese History, Hanoi.

-

The boy Buddha rising up from lotus. Crimson and gilded wood, Trần-Hồ dynasty, 14th–15th century. Statue for worship. National Museum of Vietnamese History, Hanoi.

-

Patterned brown glazed ceramic jar with lotus and chrysanthemum motifs from Nam Định Province (13th–14th century)

-

Bronze ceremonial helmet from the Tran dynasty in Dai-Viet

Family tree

|

| Thái Tổ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thái Tông | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thánh Tông | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nhân Tông | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anh Tông | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minh Tông | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nghệ Tông | Hiến Tông | Dụ Tông | Duệ Tông | Cung Túc | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thuận Tông | Phế Đế | Nhật Lễ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thiếu Đế | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

baldanzawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cengagewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Taylor 2013, pp. 108–121.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 259.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 262–263.

- ^ National Bureau for Historical Record 1998, p. 292.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 250.

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim 1971, p. 70.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 273.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 91.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 281.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 90.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 270.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 94.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 288–291.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 292.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 294.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 294–295.

- ^ "Chuyển đổi ngày âm dương – Lunar calendar converter". Retrieved 22 March 2021. The second option on the left tab allows for the lunar date to be entered on the top green row, and gives a conversion to Gregorian date, and vice versa.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 296.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 96.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 166.

- ^ Hall 2008, p. 161.

- ^ a b Chapuis 1995, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Trần Trọng Kim 1971, p. 50.

- ^ a b Chapuis 1995, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 179.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 95.

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim 1971, p. 73.

- ^ Philippe Truong (2007). The Elephant and the Lotus: Vietnamese Ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. MFA Pub. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87846-717-4.

- ^ Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000–1800. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-988-8083-34-3.

- ^ Dương Quảng Hàm 1968, pp. 232–238.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 153.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 178.

- ^ a b Trần Trọng Kim 1971, p. 53.

- ^ Tham Seong Chee 1981, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Tham Seong Chee 1981, p. 305.

- ^ Tham Seong Chee 1981, pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b c Lê Mạnh Thát. "A Complete Collection of Trần Nhân Tông's Works". Thuvienhoasen.org. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ Dror, Olga (1997). Cult, culture, and authority: Princess Liễu Hạnh in Vietnamese history. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 14–28. ISBN 0-8248-2972-7.

- ^ Dương Quảng Hàm 1968, p. 292.

- ^ Kevin Bowen; Ba Chung Nguyen; Bruce Weigl (1998). Mountain river: Vietnamese poetry from the wars, 1948–1993 : a bilingual collection. Univ of Massachusetts Press. pp. xxiv. ISBN 1-55849-141-4.

- ^ "Hàn Thuyên". Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ Dương Quảng Hàm 1968, p. 294.

- ^ a b Miller & Williams 2008, p. 249.

- ^ Miller & Williams 2008, p. 274.

- ^ Chapuis 1995, p. 89.

- ^ Miller & Williams 2008, pp. 278–279.

- ^ a b c Trương Hữu Quýnh, Đinh Xuân Lâm & Lê Mậu Hãn 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 263.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 180.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 171.

- ^ Adriano (di St. Thecla), Olga Dror (2002). Opusculum de sectis apud Sinenses et Tunkinenses: A small treatise on the sects among the Chinese and Tonkinese. Olga Dror (trans.). SEAP Publications. p. 128. ISBN 0-87727-732-X.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 163.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 168–169.

- ^ "Nguyễn Hiền". Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ a b "Lê Văn Hưu". Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 172.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 217.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 289.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 176.

- ^ a b Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 233.

- ^ a b c Mai Hồng 1989, p. 20.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 166.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 182.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 267.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 169.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 234.

- ^ "Đặng Lộ". Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 246.

- ^ "Đặng Lộ: Nhà thiên văn học" (in Vietnamese). Baobinhduong.org.vn. 2006-02-28. Retrieved 2009-12-08.[dead link]

- ^ "Trần". Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ^ Tuyet Nhung Tran & Reid 2006, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Tuyet Nhung Tran & Reid 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Tuyet Nhung Tran & Reid 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ [[#CITEREFAlan_Kam-leung_ChanClanceyHui-Chieh_Loy2001|Alan Kam-leung Chan, Clancey & Hui-Chieh Loy 2001]], p. 265.

- ^ Jan Van Alphen; Anthony Aris (1995). Oriental medicine: an illustrated guide to the Asian arts of healing. Serindia Publications, Inc. pp. 210–214. ISBN 0-906026-36-9.

- ^ a b Alan Kam-leung Chan, Clancey & Hui-Chieh Loy 2001, p. 265.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 257.

- ^ Phạm Văn Sơn 1983, p. 215.

- ^ Nguyễn Xuân Việt (2008-12-26). "Y học cổ truyền của tỉnh Hải Dương trong hiện tại và tương lai" (in Vietnamese). Haiduong Department of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ a b "Tuệ Tĩnh". Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ Alan Kam-leung Chan, Clancey & Hui-Chieh Loy 2001, pp. 265–266.

Sources

- Alan Kam-leung Chan; Clancey, Gregory K.; Hui-Chieh Loy (2001), Historical perspectives on East Asian science, technology, and medicine, World Scientific, ISBN 9971-69-259-7

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995), A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-29622-7

- Dương Quảng Hàm (1968), Việt-Nam văn-học (in Vietnamese), Trung-Tâm-Học-Liệu

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K. (2012), Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-51110-0

- Hall, Kenneth R., ed. (2008), Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400–1800, Comparative Urban Studies, vol. 1, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-2835-0, retrieved 7 August 2013

- Mai Hồng (1989), Các trạng nguyên nước ta (in Vietnamese), Hanoi: Education Publishing House

- Miller, Terry E.; Williams, Sean (2008), The Garland handbook of Southeast Asian music, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-96075-5

- National Bureau for Historical Record (1998), Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục (in Vietnamese), Hanoi: Education Publishing House

- Ngô Sĩ Liên (1993), Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (in Vietnamese) (Nội các quan bản ed.), Hanoi: Social Science Publishing House

- Phạm Văn Sơn (1983), Việt sử toàn thư (in Vietnamese), Japan: Association of Vietnameses in Japan

- Taylor, K. W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8

- Tham Seong Chee (1981), Essays on Literature and Society in Southeast Asia: Political and Sociological Perspectives, Singapore: NUS Press, ISBN 9971-69-036-5

- Tuyet Nhung Tran; Reid, Anthony J. S. (2006), Việt Nam Borderless Histories, Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-21770-9

- Trần Trọng Kim (1971), Việt Nam sử lược (in Vietnamese), Saigon: Center for School Materials

- Trương Hữu Quýnh; Đinh Xuân Lâm; Lê Mậu Hãn (2008), Đại cương lịch sử Việt Nam (in Vietnamese), Hanoi: Education Publishing House

- Whitmore, John K. (2022). "The Sông Cái (Red River) Delta, the Chinese Diaspora, and the Trần/Chen Clan of Ðại Việt". Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Asian Interactions. 19 (2): 210–232. doi:10.1163/26662523-12340011. S2CID 247914991.

Further reading

- Stuart-Fox, Martin (2003), China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence, Allen & Unwin, ISBN 1-86448-954-5

- Lockard, Craig (2009), Southeast Asia in World History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516075-8

- Tarling, Nicholas (1992), The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume one: From Early Times to C. 1800, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-35505-2

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1991), The Birth of Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-07417-3

- Thiện Đỗ (2003), Vietnamese supernaturalism: views from the southern region, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30799-6

- Wolters, O. W. (2009), Monologue, Dialogue, and Tran Vietnam, Cornell University Library, hdl:1813/13117