Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman | |

|---|---|

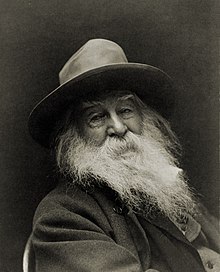

Walt Whitman, 1887 | |

| Born | May 31, 1819 West Hills, Town of Huntington, Long Island, New York |

| Died | March 26, 1892 (aged 72) Camden, New Jersey |

Walter Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, journalist, and humanist. He was a part of the transition between Transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse.[1] His work was very controversial in its time, particularly his poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sexuality.

Born on Long Island, Whitman worked as a journalist, a teacher, a government clerk, and a volunteer nurse during the American Civil War in addition to publishing his poetry. Early in his career, he also produced a temperance novel, Franklin Evans (1842). Whitman's major work, Leaves of Grass, was first published in 1855 with his own money. The work was an attempt at reaching out to the common person with an American epic. He continued expanding and revising it until his death in 1892. After a stroke towards the end of his life, he moved to Camden, New Jersey where his health further declined. He died at age 72 and his funeral became a public spectacle.[2][3]

Whitman's sexuality is often discussed alongside his poetry. Though he is usually labeled as either homosexual or bisexual,[4] it is unclear if Whitman ever had a sexual relationship with another man.[5] Whitman was concerned with politics throughout his life. He supported the Wilmot Proviso and opposed the extension of slavery generally, but did not believe in the abolitionist movement.

Life and work

Early life

Walter Whitman was born on May 31, 1819 in West Hills, Town of Huntington, Long Island, to Quaker parents, Walter and Louisa Van Velsor Whitman. He was the second of nine children[6] and was immediately nicknamed "Walt" to distinguish him from his father.[7] Walter Whitman, Sr. named three of his seven sons after American leaders: Andrew Jackson, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. The oldest was named Jesse and another boy died unnamed at the age of six months. The couple's sixth son, the youngest, was named Edward.[7] At age four, Whitman moved with his family from West Hills to Brooklyn, living in a series of homes in part due to bad investments.[8] Whitman looked back on his childhood as generally restless and unhappy due to his family's difficult economic status.[9] One happy moment he later recalled was when he was lifted in the air and kissed on the cheek by Marquis de Lafayette during a celebration in Brooklyn on July 4, 1825.[10]

At age eleven Whitman concluded formal schooling.[11] He then sought employment, due to his family's financial situation, originally as an office boy for two lawyers and later as an apprentice and printer's devil for the weekly Long Island newspaper the Patriot, edited by Samuel E. Clements.[12] Here, Whitman learned about the printing press and typesetting.[13] He may have written "sentimental bits" of filler material for occasional issues.[14] Clements aroused controversy when he and two friends attempted to dig up the corpse of Elias Hicks to create a plaster mold of his head.[15] Clements left the Patriot shortly after, possibly as a result of the controversy.[16]

Early career

The following summer Whitman worked for another printer, Erastus Worthington, in Brooklyn.[17] His family moved back to West Hills in the spring, but Whitman remained and took a job at the shop of Alden Spooner, editor of the leading Whig weekly newspaper the Long-Island Star.[17] While at the Star, Whitman became a regular patron of the local library, joined a town debating society, began attending theater performances,[18] and anonymously published some of his earliest poetry in the New York Mirror.[19] At age 16 in May 1835, Whitman left the Star and Brooklyn.[20] He moved to New York City to work as a compositor[21] though, in later years, Whitman could not remember where.[22] He attempted to find further work but had difficulty in part due to a severe fire in the printing and publishing district[22] and in part due to a general collapse in the economy leading up to the Panic of 1837.[23] In May 1836, he rejoined his family, now living in Hempstead, Long Island.[24] Whitman taught intermittently at various schools until the spring of 1838, though he was not satisfied as a teacher.[25]

After his teaching attempts, Whitman went back to Huntington, New York to found his own newspaper, the Long-Islander. Whitman served as publisher, editor, pressman, and distributor and even provided home delivery. After ten months, he sold the publication to E. O. Crowell, whose first issue appeared on July 12, 1839.[26] No copies of the Long-Islander published under Whitman survive.[27] By the summer of 1839, he found a job as a typesetter in Jamaica, Queens with the Long Island Democrat, edited by James J. Brenton.[26] He left shortly thereafter, and made another attempt at teaching from the winter of 1840 to the spring of 1841, then moved to New York City in May.[28] There, he initially worked a low-level job at the New World, working under Park Benjamin, Sr. and Rufus Wilmot Griswold.[29] He continued working for short periods of time for various newspapers, particularly as editor of the Brooklyn Eagle for two years, as well as contributing freelance fiction and poetry throughout the 1840s.[30]

Leaves of Grass

Whitman claimed that after years of competing for "the usual rewards", he determined to become a poet.[31] He first experimented with a variety of popular literary genres which appealed to the cultural tastes of the period.[32] As early as 1850, he began writing what would become Leaves of Grass,[33] a collection of poetry which he would continue editing and revising until his death.[34] Whitman intended to write a distinctly American epic[35] and used free verse with a cadence based on the Bible.[36] At the end of June 1855, Whitman surprised his brothers with the already-printed first edition of Leaves of Grass. George "didn't think it worth reading".[37]

Whitman paid for the publication of the first edition of Leaves of Grass himself[37] and had it printed at a local print shop during their breaks from commercial jobs.[38] 795 copies were printed,[39] though the author's name was not given. Instead, facing the title page was an engraved portrait done by Samuel Hollyer.[40] The book received its strongest praise from Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote a flattering five page letter to Whitman and spoke highly of the book to friends.[41] The first edition of Leaves of Grass was widely distributed and stirred up significant interest,[42] in part due to Emerson's approval,[43] but was occasionally criticized for the seemingly "obscene" nature of the poetry.[44] Geologist John Peter Lesley wrote to Emerson, calling the book "trashy, profane & obscene" and the author "a pretentious ass".[45] On July 11, 1855, a few days after Leaves of Grass was published, Whitman's father died at the age of 65.[46]

In the months following the first edition of Leaves of Grass, critical responses began focusing more on the potentially offensive sexual themes. Though the second edition was already printed and bound, the publisher almost did not release it.[47] In the end, the edition went to retail, with 20 additional poems,[48] in August 1856.[49] Leaves of Grass was revised and re-released in 1860[50] again in 1867, and several more times throughout the remainder of Whitman's life. Several well-known writers admired the work enough to visit Whitman, including Bronson Alcott and Henry David Thoreau.[51]

Amidst the first publications of Leaves of Grass, Whitman had financial difficulty and was forced to work as a journalist again, specifically with the Brooklyn's Daily Times starting in May 1857.[52] As an editor, he oversaw the paper's contents, contributed book reviews, and wrote editorials.[53] He left the job in 1859, though it is unclear if he was fired or chose to leave.[54] Whitman, who typically kept detailed notebooks and journals, left very little information about himself in the late 1850s.[55]

Civil War years

As the American Civil War was beginning, Whitman published his poem "Beat! Beat! Drums!" as a patriotic rally call for the North.[56] Whitman's brother George had joined the Union army and began sending Whitman several vividly detailed letters of the battle front.[57] On December 16, 1862, a listing of fallen and wounded soldiers in the New York Tribune included "First Lieutenant G. W. Whitmore", which Whitman worried was a reference to his brother George.[58] He made his way south immediately to find him, though his wallet was stolen on the way.[59] "Walking all day and night, unable to ride, trying to get information, trying to get access to big people", Whitman later wrote,[60] he eventually found George alive, with only a superficial wound on his cheek.[58] Whitman, profoundly affected by seeing the wounded soldiers and the heaps of their amputated limbs, left for Washington on December 28, 1862 with the intention of never returning to New York.[59]

In Washington, D.C., Whitman's friend Charley Eldridge helped him obtain part-time work in the army paymaster's office, leaving time for Whitman to volunteer as a nurse in the army hospitals.[61] He would write of this experience in "The Great Army of the Sick", published in a New York newspaper in 1863[62] and, 12 years later, in a book called Memoranda During the War.[63] He then contacted Emerson, this time to ask for help in obtaining a government post.[59] Friend John Trowbridge passed on a letter of recommendation from Emerson to Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury, hoping he would grant Whitman a position in that department. Chase, however, did not want to hire the author of a disreputable book, referring to Leaves of Grass.[64]

The Whitman family had a difficult end to 1864. On September 30, 1864, Whitman's brother George was captured by Confederates in Virginia,[65] another brother, Andrew Jackson, died of tuberculosis compounded by alcoholism on December 3.[66] That month, Whitman committed his brother Jesse to the Kings County Lunatic Asylum.[67] Whitman's spirits were raised, however, when he finally got a better-paying government post — a low grade clerk in the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior — thanks to O'Connor, who had written to William Tod Otto, Assistant Secretary of the Interior.[68] Whitman began the new appointment on January 24, 1865, with a yearly salary of $1,200.[69] A month later, on February 24, 1865, George was released from capture and granted a furlough because of his poor health.[68] By May 1, Whitman received a promotion to a slightly higher clerkship[69] and published Drum-Taps.[70]

Effective June 30, 1865, however, Whitman was fired from his job.[70] His dismissal came from the new Secretary of the Interior, former Iowa Senator James Harlan.[69] Though Harlan dismissed several clerks who "were seldom at their respective desks", he may have fired Whitman on moral grounds after finding an 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.[71] O'Connor protested until J. Hubley Ashton had Whitman transferred to the Attorney General's office on July 1.[72] O'Connor, though, was still upset and vindicated Whitman by publishing a biased and exaggerated biographical study, The Good Gray Poet, in January 1866. The fifty-cent pamphlet defended Whitman as a wholesome patriot, established the poet's nickname and increased his popularity.[73] Also aiding in his popularity was the publication of "O Captain! My Captain!", a relatively conventional poem to Abraham Lincoln, the only poem to be anthologized during Whitman's lifetime.[74]

Part of Whitman's role in the Attorney General's office was interviewing former Confederate soldiers for Presidential pardons. "There are real characters among them", he later wrote, "and you know I have a fancy for anything out of the ordinary."[75] In August 1866, he took a month off in order to prepare a new edition of Leaves of Grass which would not be published until 1867 after difficulty in finding a publisher.[76] He hoped it would be its last edition.[77] In February 1868 Poems of Walt Whitman was published in England thanks to the influence of William Michael Rossetti,[78] with minor changes which Whitman reluctantly approved.[79] The edition became popular in England, especially with endorsements from the highly-respected Anne Gilchrist.[80] Another edition of Leaves of Grass was issued in 1871, the same year it was mistakenly reported that its author died in a railroad accident.[81] As Whitman's international fame increased, he remained working in the attorney general's office until January of 1872.[82] He spent much of 1872 caring for his mother who was now nearly eighty and struggling with arthritis.[83] He also traveled and was invited to Dartmouth College to give the commencement address on June 26, 1872.[84]

Health decline and death

Early in 1873, Whitman suffered a paralytic stroke; his mother died in May the same year. Both events were difficult for Whitman and left him depressed.[85] He moved to Camden, New Jersey to live with his brother George, paying room and board until he bought his own house on Mickle St. in 1884.[86] Around this time, he began socializing with Mary Oakes Davis, the widow of a sea captain, who lived nearby.[87] She moved in with Whitman on February 24, 1885 to serve as his housekeeper in exchange for free rent. She brought with her a cat, a dog, two turtledoves, a canary, and other assorted animals.[88] During this time, Whitman produced further editions of Leaves of Grass in 1876, 1881, and 1889.

As the end of 1891 approached, he prepared a final edition of Leaves of Grass, an edition which has been nicknamed the "Deathbed Edition". He wrote, "L. of G. at last complete—after 33 y'rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old".[89] Preparing for death, Whitman commissioned a granite mausoleum shaped like a house for $4,000[90] and visited it often during construction.[91] In the last week of his life, he was too weak to lift a knife or fork and wrote: "I suffer all the time: I have no relief, no escape: it is monotony — monotony — monotony — in pain."[92]

Whitman died on March 26, 1892.[93] An autopsy revealed his lungs had diminished to one-eighth their normal breathing capacity, a result of bronchial pneumonia,[90] and that an egg-sized abscess on his chest had eroded one of his ribs. The cause of death was officially listed as "pleurisy of the left side, consumption of the right lung, general miliary tuberculosis and parenchymatous nephritis."[94] A public viewing of his body was held at his Camden home; over one thousand people visited in three hours[2] and Whitman's oak coffin was barely visible because of all the flowers and wreaths left for him.[95] He was buried in his tomb at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden four days after his death.[2] Another public ceremony was held at the cemetery, with friends giving speeches, live music, and refreshments.[3] Later, the remains of Whitman's parents and two of his brothers and their families were moved to the mausoleum.[96]

Lifestyle and beliefs

Alcohol

Whitman was a vocal proponent of temperance and rarely drank alcohol. He once claimed he did not taste "strong liquor" until he was thirty[97] and occasionally argued for prohibition.[98] One of his earliest long fiction works, the novel Franklin Evans; or, The Inebriate, first published November 23, 1842, is a temperance novel.[99] Whitman wrote the novel at the height of popularity of the Washingtonian movement though the movement itself was plagued with contradictions, as was Franklin Evans.[100] Years later Whitman claimed he was embarrassed by the book[101] and called it a "damned rot".[102] He dismissed it by saying he wrote the novel in three days solely for money while he was under the influence of alcohol himself.[103] Even so, he wrote other pieces recommending temperance, including The Madman and a short story "Reuben's Last Wish".[104]

Poetic theory

Whitman wrote in the preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, "The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it." He believed there was a vital, symbiotic relationship between the poet and society.[105] This connection was emphasized especially in "Song of Myself" by using an all-powerful first-person narration.[106] As an American epic, it deviated from the historic use of an elevated hero and instead assumed the identity the common people.[107] Leaves of Grass also responds to the impact recent urbanization in the United States has on the masses.[108]

Religion

Whitman was deeply influenced by deism. He denied any one faith was more important than another, and embraced all religions equally.[109] In "Song of Myself", he gave an inventory of major religions and indicated he respected and accepted all of them — a sentiment he further emphasized in his poem "With Antecedents", affirming: "I adopt each theory, myth, god, and demi-god, / I see that the old accounts, bibles, genealogies, are true, without exception".[109] In 1874, he was invited to write a poem about the Spiritualism movement, to which he responded, "It seems to me nearly altogether a poor, cheap, crude humbug."[110] Whitman was a religious skeptic: though he accepted all churches, he believed in none.[109]

Sexuality

Whitman's sexuality is sometimes disputed, although often assumed to be bisexual based on his poetry.[4] The concept of heterosexual and homosexual personalities was invented in 1868, and it was not widely promoted until Whitman was an old man. Whitman's poetry depicts love and sexuality in a more earthy, individualistic way common in American culture before the medicalization of sexuality in the late 1800s.[111] Though Leaves of Grass was often labeled pornographic or obscene, only one critic remarked on its author's presumed sexual activity: in a November 1855 review, Rufus Wilmot Griswold suggested Whitman was guilty of "that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians".[112] Whitman had intense friendships with many men throughout his life. Some biographers have claimed that he may not have actually engaged in sexual relationships with men,[5] while others cite letters, journal entries and other sources which they claim as proof of the sexual nature of some of his relationships. [113]

Biographer David S. Reynolds described a man named Peter Doyle as being the most likely candidate for the love of Whitman's life.[114] Doyle was a bus conductor whom he met around 1866. They were inseparable for several years. Interviewed in 1895, Doyle said: "We were familiar at once — I put my hand on his knee — we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip — in fact went all the way back with me."[115] A more direct second-hand account comes from Oscar Wilde. Wilde met Whitman in America in 1882, and wrote to the homosexual rights activist George Cecil Ives that there was "no doubt" about the great American poet's sexual orientation — "I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips," he boasted.[116] The only explicit description of Whitman's sexual activities is second hand. In 1924 Edward Carpenter, then an old man, described an erotic encounter he had had in his youth with Whitman to Gavin Arthur, who recorded it in detail in his journal.[117] Late in his life, when Whitman was asked outright if his series of "Calamus" poems were homosexual, he chose not to respond.[118]

There is also some evidence that Whitman may have had sexual relationships with women. He had a romantic friendship with a New York actress named Ellen Grey in the spring of 1862, but it is not known whether or not it was also sexual. He still had a photo of her decades later when he moved to Camden and referred to her as "an old sweetheart of mine".[119] In a letter dated August 21, 1890 he claimed, "I have had six children - two are dead". This claim has never been corroborated.[120] Toward the end of his life, he often told stories of previous girlfriends and sweethearts and denied an allegation from the New York Herald that he had "never had a love affair".[121]

Shakespeare authorship

Whitman was a proponent of the Shakespeare authorship question, refusing to believe in the historic attribution of the works to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon. Whitman comments in his November Boughs (1888) regarding Shakespeare's historical plays:

"Conceiv'd out of the fullest heat and pulse of European feudalism -personifying ill unparalleled ways the medieval aristocracy, its towering spirit of ruthless and gigantic caste, with its own peculiar air and arrogance (no mere imitation) -only one of the "wolfish earls" so plenteous in the plays themselves, or some born descendant and knower, might seem to be the true author of those amazing works -works in some respects greater than anything else in recorded literature."[122]

Slavery

Whitman opposed the extension of slavery in the United States and supported the Wilmot Proviso.[123] He was not necessarily an abolitionist and believed the movement did more harm than good. He once wrote that the abolitionists had, in fact, slowed the advancement of their cause by their "ultraism and officiousness".[124] His main concern was that their methods disrupted the democratic process, as did the refusal of the Southern states to put the interests of the nation as a whole above their own.[123] Whitman also subscribed to the widespread opinion that even free African-Americans should not vote[125] and was concerned at the increasing number of African-Americans in the legislature.[126]

Legacy and influence

Walt Whitman has been claimed as America's first "poet of democracy", a title meant to reflect his ability to write in a singularly American character. A British friend of Walt Whitman, Mary Smith Whitall Costelloe, wrote: "You cannot really understand America without Walt Whitman, without Leaves of Grass... He has expressed that civilization, 'up to date,' as he would say, and no student of the philosophy of history can do without him."[127] Modernist poet Ezra Pound called Whitman "America's poet... He is America."[128] Andrew Carnegie called him "the great poet of America so far".[129]

Whitman considered himself a messiah-like figure in poetry.[130] Others agreed: one of his admirers, William Sloane Kennedy, speculated that "people will be celebrating the birth of Walt Whitman as they are now the birth of Christ".[131] Whitman's work breaks the boundaries of poetic form and is generally prose-like.[1] He also used unusual images and symbols in his poetry, including rotting leaves, tufts of straw, and debris.[132] He also openly wrote about death and sexuality, including prostitution.[133] He is often labeled as the father of free verse, though he did not invent it.[1]

Whitman's vagabond lifestyle was adopted by the Beat movement and its leaders such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac in the 1950s and 1960s as well as anti-war poets like Adrienne Rich and Gary Snyder.[134] Whitman also influenced Bram Stoker, author of Dracula, and was the model for the character of Dracula. Stoker said in his notes that Dracula represented the quintessential male which, to Stoker, was Whitman, with whom he corresponded until Whitman's death.[135]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 314

- ^ a b c Loving, 480

- ^ a b Reynolds, 589

- ^ a b Buckham, Luke. "Walt Whitman's Vision of Liberty", Keene Free Press. October 11, 2006.

- ^ a b Loving, 19

- ^ Miller, 17

- ^ a b Loving, 29

- ^ Loving, 30

- ^ Reynolds, 24

- ^ Reynolds, 33–34

- ^ Loving, 32

- ^ Reynolds, 44

- ^ Kaplan, 74

- ^ Callow, 30

- ^ Callow, 29

- ^ Loving, 34

- ^ a b Reynolds, 45

- ^ Callow, 32

- ^ Kaplan, 79

- ^ Kaplan, 77

- ^ Callow, 35

- ^ a b Kaplan, 81

- ^ Loving, 36

- ^ Callow, 36

- ^ Loving, 37

- ^ a b Reynolds, 60

- ^ Loving, 38

- ^ Kaplan, 93–94

- ^ Callow, 56

- ^ Reynolds, 83–84

- ^ Kaplan, 185

- ^ Reynolds, 85

- ^ Loving, 154

- ^ Miller, 55

- ^ Miller, 155

- ^ Kaplan, 187

- ^ a b Callow, 226

- ^ Loving, 178

- ^ Kaplan, 198

- ^ Callow, 227

- ^ Kaplan, 203

- ^ Reynolds, 340

- ^ Callow, 232

- ^ Loving, 414

- ^ Kaplan, 211

- ^ Kaplan, 229

- ^ Reynolds, 348

- ^ Callow, 238

- ^ Kaplan, 207

- ^ Loving, 238

- ^ Reynolds, 363

- ^ Callow, 225

- ^ Reynolds, 368

- ^ Loving, 228

- ^ Reynolds, 375

- ^ Callow, 283

- ^ Reynolds, 410

- ^ a b Kaplan, 268

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 411

- ^ Callow, 286

- ^ Callow, 293

- ^ Kaplan, 273

- ^ Callow, 297

- ^ Callow, 295

- ^ Loving, 281

- ^ Kaplan, 293–294

- ^ Reynolds, 454

- ^ a b Loving, 283

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 455

- ^ a b Loving, 290

- ^ Loving, 291

- ^ Kaplan, 304

- ^ Reynolds, 456-457

- ^ Kaplan, 309

- ^ Loving, 293

- ^ Kaplan, 318–319

- ^ Loving, 314

- ^ Callow, 326

- ^ Kaplan, 324

- ^ Callow, 329

- ^ Loving, 331

- ^ Reynolds, 464

- ^ Kaplan, 340

- ^ Loving, 341

- ^ Miller, 33

- ^ Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of American Authors. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1991: 141. ISBN 0891331808.

- ^ Loving, 432

- ^ Reynolds, 548

- ^ Reynolds, 586

- ^ a b Loving, 479

- ^ Kaplan, 49

- ^ Reynolds, 587

- ^ Callow, 363

- ^ Reynolds, 588

- ^ Reynolds, 588

- ^ Kaplan, 50

- ^ Loving, 71

- ^ Callow, 75

- ^ Loving, 74

- ^ Reynolds, 95

- ^ Reynolds, 91

- ^ Loving, 75

- ^ Reynolds, 97

- ^ Loving, 72

- ^ Reynolds, 5

- ^ Reynolds, 324

- ^ Miller, 78

- ^ Reynolds, 332

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 237

- ^ Loving, 353

- ^ D'Emilio and Freeman (1997). Intimate Matters - A History of Sexuality in America ISBN 0-226-14264-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Loving, 184–185

- ^ Norton, Rictor "Walt Whitman, Prophet of Gay Liberation" from The Great Queens of History, updated 18 Nov. 1999

- ^ Reynolds, 487

- ^ Kaplan, 311–312

- ^ McKenna, Neil. The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde. Century, 2003: 33. ISBN 0465044387.

- ^ Kantrowitz, Arnie. "Edward Carpenter". Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia, J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings, eds. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998.

- ^ Reynolds, 527

- ^ Callow, 278

- ^ Loving, 123

- ^ Reynolds,490

- ^ Nelson, Paul A. "Walt Whitman on Shakespeare". Reprinted from The Shakespeare Oxford Society Newsletter, Fall 1992: Volume 28, 4A.

- ^ a b Reynolds, 117

- ^ Loving, 110

- ^ Reynolds, 473

- ^ Reynolds, 470

- ^ Reynolds, 4

- ^ Pound, Ezra. "Walt Whitman", Whitman, Roy Harvey Pearce, ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1962: 8

- ^ Kaplan, 22

- ^ Callow, 83

- ^ Loving, 475

- ^ Kaplan, 233

- ^ Loving, 314

- ^ Loving, 181

- ^ Nuzum, Eric. The Dead Travel Fast. 141–147.

Bibliography

- Callow, Philip. From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1992. ISBN 0929587952

- Kaplan, Justin. Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979. ISBN 0671225421

- Loving, Jerome. Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0520226879

- Miller, James E., Jr. Walt Whitman. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc. 1962

- Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. ISBN 0679767096

External links

- Poets.org - Biography, related essays, poems, and reading guides from the Academy of American Poets

- Walt Whitman: Online Resources at the Library of Congress

- The Walt Whitman Archive includes all editions of "Leaves of Grass" in page-images and transcription, as well as manuscripts, criticism, and biography

- Listen to selections from Walt Whitman's "Leaves of Grass" - RealAudio

- Walt Whitman Page by Camden County, New Jersey Historical Society

- MS Lowell 15. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892. Passage to India : autograph manuscript; Washington, 1870. 21s. (21p.) Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Walt Whitman household in NJ in 1880 census

Sites

- 1819 births

- 1892 deaths

- 19th century philosophers

- American essayists

- American journalists

- American nurses

- Dutch Americans

- American philosophers

- American poets

- American Quakers

- American spiritual writers

- Bisexual writers from the United States

- Brooklyn Eagle

- Classical liberals

- New York writers

- People from Camden, New Jersey

- People from Long Island

- People from Hempstead, New York

- People of the American Civil War

- Queer studies

- American Unitarian Universalists

- Western mystics