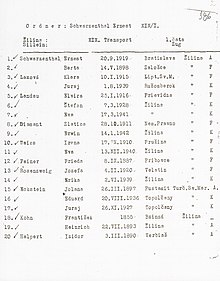

List of Holocaust transports from Slovakia

Restored train car used to transport Slovak Jews. | |

| Date | 1942 and 1944–1945 |

|---|---|

| Location | Slovak Republic, General Governorate, Nazi Germany |

| Target | Slovak Jews |

| Organised by | Slovak Republic, Nazi Germany |

| Deaths | 57,000 (1942) 10,000 (1944–1945) Total: 67,000 |

During the Holocaust, most of Slovakia's Jewish population was deported in two waves—in 1942 and in 1944–1945. In 1942, there were two destinations: 18,746 Jews were deported in eighteen transports to Auschwitz concentration camp and another 39,000–40,000[a] were deported in thirty-eight transports to Majdanek and Sobibór extermination camps and various ghettos in the Lublin district of the General Governorate. A total of 57,628 people were deported; only a few hundred returned. In 1944 and 1945, 13,500 Jews were deported to Auschwitz (8,000 deportees), with smaller numbers sent to the Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück, Bergen-Belsen, and Theresienstadt concentration camps. Altogether, these deportations resulted in the deaths of around 67,000 of the 89,000 Jews living in Slovakia.

Background

In the political crisis that followed the September 1938 Munich Agreement,[1] the conservative, ethnonationalist Slovak People’s Party[2][3] unilaterally declared a state of autonomy for Slovakia within Czechoslovakia. Slovak Jews, who numbered 89,000 in 1940, were targeted for persecution. In November 1938, 7,500 Jews (impoverished or without Slovak citizenship) were deported to the Hungarian border. Although they were allowed to return within a few months, these deportations were a rehearsal for those to follow in 1942.[4][5]

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak State declared independence with German support. Many Jews lost their jobs and property due to Aryanization, which resulted in large numbers of them becoming impoverished. This became a pressing social problem for the Slovak government, which it "solved" by deporting the unemployed Jews. Slovakia initially agreed with the German government to deport 20,000 Jews of working age to German-occupied Poland, paying Nazi Germany 500 Reichsmarks each (supposedly to cover the cost of resettlement). However, this was only the first step in the deportation of all Jews, because deporting workers while leaving their families behind would worsen the economic situation of the remaining Jews.[6][7]

In the meantime, Nazi Germany had been working towards the Final Solution—the murder of all the Jews that it could reach. In 1939, the Lublin District in German-occupied Poland was set aside as a "Jewish reservation". In 1942 it became a reception point for Jews from Nazi Germany and Slovakia. Starting in late 1941, the Schutzstaffel (SS) began planning for the deportation of the Jews in Lublin to the Operation Reinhard death camps—Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka—to free up space for the Slovak and German Jews.[8]

1942

Initial phase

The original deportation plan, approved in February 1942 by the German and Slovak governments, entailed the deportation of 7,000 single women aged 16–35 to Auschwitz and 13,000 single men aged 16–45 to Majdanek as forced laborers.[7][9] The cover name for the operation was Aktion David.[10][11] The SS officer and Judenberater (adviser on Jewish issues) Dieter Wisliceny and Slovak officials promised that deportees would not be mistreated and would be allowed to return home after a fixed period.[12] Initially, many Jews believed that it was better to report for deportation than risk reprisals against their families for failing to do so.[13] However, 3,000 of the 7,000 women who were supposed to be deported refused to report as ordered. Methods of escape included sham marriages, being sent away to live with relatives, or being hidden temporarily by non-Jews. The Hlinka Guard struggled to meet its targets;[14] as a result, only 3,800 women and 4,500 men were deported during the initial phase of deportations.[15] Nevertheless, they opened "a new chapter in the history of the Holocaust" because the Slovak women were the first Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz. Their arrival precipitated the conversion of the camp into an extermination camp.[16]

Department 14, a subsidiary of Slovakia's Central Economic Office, organized the transports,[17] while the Slovak Transport Ministry provided the cattle cars.[18][19] Members of the Hlinka Guard, the Freiwillige Schutzstaffel (FS) and the gendarmerie were in charge of rounding up the Jews, guarding the transit centers, and eventually loading them into overcrowded cattle cars for deportation.[20][19] Transports were timed to reach the Slovak border near Čadca at 04:28.[21][b] In Zwardon at 08:30, the Hlinka Guard turned the transports over to the German Schutzpolizei.[25][20][26] The transports would arrive in Auschwitz the same afternoon[27] and at Majdanek the next morning.[26]

On 25 March 1942, the first transport train left Poprad at 20:00.[23][28] Before its departure, Wisliceny spoke to the deportees on the platform, saying that they would be allowed to return home after they finished the work that Germany had planned for them. The first deportees were unaware of what lay ahead and tried to be optimistic. According to survivors, songs in Hebrew and Slovak were sung as the first two transports of women to Auschwitz left the platforms.[29] Most of the Slovak Jewish women deported to Auschwitz in 1942 who survived the war were from the first two transports in March, because they were younger and stronger.[30] Those from eastern Slovakia were especially likely to be young, because most Jews from that area were Haredim and tended to marry young: more than half were aged 21 or younger. The women deported from Bratislava were older on average because they married later in life and some did not marry at all; only 40 percent were 21 or younger.[28]

| Date | Source | Destination | Number of deportees | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–26 March[23][31] | Poprad | Auschwitz | 997[27] | |||

| 27 March | Žilina | Majdanek | 1000[32] | |||

| 27–28 March | Patrónka | Auschwitz | 798,[31][33] 1000,[34] or 1002[22] | |||

| 28–30 March | Sereď | Majdanek | 1000[32][35] | |||

| 30–31 March | Nováky | Majdanek | 1003[32][21] | |||

| 1–2 April | Patrónka | Auschwitz | 965[36][37] | |||

| 2[23]–3 April | Poprad | Auschwitz | 997[31][38] | |||

| 5 April | Žilina | Majdanek | 1495[32] | |||

| Most information can also be verified to Fatran 2007, p. 180 | ||||||

Transports to Lublin

SS leader Reinhard Heydrich visited Bratislava on 10 April 1942. He and Vojtech Tuka agreed that further deportations would target whole families and eventually remove all Jews from Slovakia.[39][40] Ostensibly, the change was to avoid separating families, but it also solved the problem of caring for the children and elderly family members of able-bodied deportees.[19] The family transports began on 11 April and took their victims to the Lublin district.[39][40] This change disrupted the SS's plans in the Lublin district. Instead of able-bodied male Slovak Jews being deported to Majdanek, the SS needed to prepare space for Slovak Jewish families in the region's overcrowded ghettos.[15] The transports from Slovakia were the largest and longest of all the deportations of Jews to the Lublin District.[26]

The trains went through two railway distribution points, in Nałęczów and Lublin, where they were met by a ranking SS officer. In Lublin, there was usually a selection and able-bodied men were selected for labor at Majdanek, while the remainder were sent to ghettos along the rail lines. For the trains that went through Nałęczów, the Jews were dispatched to locations seeking forced labor, usually without separating families.[41] Most of the trains brought their victims (30,000 in total)[42] to ghettos whose inhabitants had been recently deported to the Bełżec or Sobibór death camps,[15] as part of a "revolving door" policy in which foreign Jews were brought in to replace those murdered.[43] The final transports to the Lublin district occurred during the first half of June 1942; ten transports stopped briefly at Majdanek, where able-bodied men (generally those aged 15–50) were selected for labor; the trains continued to Sobibór, where the remaining victims were murdered.[39][44]

The victims were given only four hours warning to prevent them from escaping. Beatings and forcible beard shaving were commonplace, as was subjecting Jews to invasive searches to uncover hidden valuables.[45] Although some guards and local officials accepted bribes to keep Jews off the transports, the victim would typically be deported on the next train.[46] Others took advantage of their power to rape Jewish women.[47] Jews were only allowed to bring 50 kilograms (110 lb) of personal items with them, but even this was frequently stolen.[48] Official exemptions were supposed to keep Jews from being deported, but local authorities sometimes deported exemption holders.[49]

Most groups stayed only briefly in the Lublin ghettos before they were deported again to the death camps, while a few remained in the ghettos for months or years.[39][50] Several thousand of the deportees ended up in the forced-labor camps in the Lublin area (such as Poniatowa, Końskowola, and Krychów).[51] Unusually, the deportees in the Lublin area were quickly able to establish contact with the Jews remaining in Slovakia, which led to extensive aid efforts.[52] However, the fate of the Jews deported from Slovakia was ultimately "sealed within the framework of Operation Reinhard", along with that of the Polish Jews.[53] Of the estimated 8,500 men who were deported directly to Majdanek, only 883 were still alive by July 1943.[15][54] (Another few thousand Slovak Jews were deported to Majdanek following the liquidation of ghettos in the Lublin district, but most of them were murdered immediately.)[54] The remaining Slovak Jews at Majdanek were shot during Operation Harvest Festival; the only significant group of Slovak Jews to remain in Lublin district was a group of about 100 at the Luftwaffe camp in Dęblin–Irena.[55]

| Date | Source | Destination | Secondary destination | Number of deportees | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11[56]–13 April[57] | Trnava | Lubartów/Majdanek | Kamionka, Firlej | 1040 | About 900 Jews arrived in Lubartów from the first transport and 680 from the second. They were soon transferred elsewhere, mostly to Firlej and Ostrów.[58] |

| 14[32]–15 April[57] | Nitra | Lubartów/Majdanek | Ostrów Lubelski | 1038 | |

| 16[34]–17 April[59] | Nitra | Rejowiec/Majdanek | Trawniki | 1048 | About 840 Jews arrived in Rejowiec.[59] |

| 20 April[59] | Nitra | Rejowiec | 1030 | ||

| 21[35]–22 April[60] | Topoľčany/Sereď | Opole | 1001 | From the five transports to Opole (totaling 4,302 deportees), only 1,400 Jews remained in the ghetto; the remainder were sent to labor camps in the area.[60] | |

| 27 April | Nové Mesto nad Váhom, Piešťany, and Hlohovec | Opole | Poniatowa | 1179–1382[61] | |

| 5[32]–7 May[57] | Trebišov | Lubartów/Majdanek | Kamionka | 1040 | 841 Slovak Jews arrived in Lubartów.[57] |

| 6[32]–8 May[62] | Michalovce | Łuków | 1038 | Slovak Jews remained at Łuków until the ghetto's liquidation on 2 May 1943.[63] | |

| 7[32]–9 May[62] | Michalovce | Łuków | 1040 | ||

| 8 May | Michalovce | Międzyrzec Podlaski | 1001[32] or 1,025[64] | ||

| 11 May[65] | Humenné | Chełm | 1009 | The SS confiscated the deportees' luggage. Some were conscripted to work for the Wasserwirtschaftsinspektion (Water Regulation Authority) at Siedliszcze. Others were deported to Sobibór extermination camp on 22–23 May. The ghetto was liquidated on 5–9 November 1942.[65] | |

| 12 May[65] | Žilina | Chełm | 1002 | ||

| 13 May[66] | Prešov | Dęblin–Irena | 1040 | On 15 October 1942, most of the Slovak Jews were deported to Treblinka extermination camp.[66] About a hundred Slovak Jewish men and women—the last significant group of Slovak Jews to survive in the Lublin area—were kept by the Luftwaffe to work as forced laborers on the nearby airfield. On 22 July 1944, they were sent to Częstochowa where a few dozen managed to survive until the liberation.[54][67][66] | |

| 14 May[66] | Prešov | Dęblin–Irena | 1040 | ||

| 17[32]–20 May[68] | Bardejov | Końskowola[68] | 1,025[68] or 1028 | The first transport to Końskowola included 700 elderly individuals and children.[68] The second arrived before 2 June. At Końskowola, Slovak Jews were employed in agricultural labor and suffered from severe hunger. In early October, the ghetto was liquidated. Except for 500 to 1,000 craftsmen who were deported to labor camps in the area, the remaining Jews were shot, either during the roundups or in ravines near Rudy.[69] | |

| 18 May | Bardejov | Opole | Poniatowa | 1015 | |

| 19 May | Vranov | Opole | Kazimierz | 1005 | |

| 20 May | Medzilaborce | Końskowola[68] | 1001[32] or 1,630[68] | ||

| 23 or 27 May[59] | Sabinov/Prešov | Rejowiec | 1630 | At Rejowiec, some Slovak Jews worked for the Jewish Ghetto Police. Either in June or August 1942, 2,000 mostly Slovak Jews were rounded up and deported to Sobibór; some 50–100 were taken out of the lines at Sobibór and sent to nearby Krychów forced-labor camp.[70][71] | |

| 24 or 28 May[59] | Stropkov/Bardejov | Rejowiec | 1022 | ||

| 24[23]–25 May[59] | Poprad | Rejowiec | 1000 | ||

| 25[60] or 26 May to 30 May[72] | Žilina | Opole | 1000 | ||

| 29 May[73] | Spišská Nová Ves | Izbica/Majdanek | 1032[32] or 1052[73] | At Izbica, Jews were held temporarily under extremely overcrowded conditions before being deported to Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibór.[74] | |

| 29[23]–30 May[73] | Poprad | Izbica/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| 30 May[23]–1 June | Poprad | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | These transports were the only ones that went directly from Slovakia to one of the Operation Reinhard extermination camps. They signified the end of the "revolving door", as German policy shifted from temporarily warehousing Jews deported to Poland in ghettos to murdering them immediately.[75][76] | |

| 2 June | Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1014 | ||

| 5 June | Bratislava/Žilina | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| 7 June | Bratislava/Žilina | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| 8 June | Žilina | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1001 | ||

| 9 June | Zvolen/Kremnica | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1019 | ||

| 11 June | Nováky | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| 12 June | Sereď/Žilina | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| 12[23]–13 June | Poprad | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| 14 June | Nováky/Žilina | Sobibór/Majdanek | 1000 | ||

| Where two primary destinations are listed, there was a selection in Lublin and able-bodied men (generally those aged 15–50 years) were sent to Majdanek.[44] All information from Büchler 1991, p. 166 unless otherwise indicated. Most information can also be verified to Fatran 2007, p. 180; Silberklang 2013, pp. 303–306. | |||||

Transports to Auschwitz

A moratorium on transports to the east was imposed on 19 June 1942 due to military campaigns on the Eastern Front. The rest of the family transports (eight in total) were therefore directed to Auschwitz. The first arrived on 4 July,[77] which led to the initial selection on the ramp at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, which became a regular event. The majority of deportees—especially mothers with children—were not chosen for forced labor and instead were killed in gas chambers.[78][79] By 1 August, most of the Jews not exempt from deportation had already been deported or had fled to Hungary to avoid the deportations, leading to a six-week halt in the transports.[80] An additional three trains departed for Auschwitz in September and October.[81]

For the first three months after the arrival of the first transport in March, Slovak Jewish women were the only female Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz.[30] In mid-August, most of the Slovak Jewish women at Auschwitz were transferred to Auschwitz II-Birkenau,[30] which was still under construction. Conditions were much worse;[78] employed mostly on outdoor labor details, most of the women died within the first four months at Birkenau.[82] Along with backbreaking physical labor and starvation, many died in epidemics of typhus or malaria and the mass executions ordered by the SS to contain the epidemics. (To contain a typhus epidemic in October 1942, the SS murdered 6,000 prisoners—mostly Slovak Jewish women—including some who were healthy; another selection on 5 December eliminated the last major group of Slovak Jewish women in Birkenau.)[83] Of the 404 men who were registered on 19 June, only 45 were still alive six weeks later.[84] By the end of 1942, 92% of the deportees had died. This left only 500 or 600 Slovak Jews still alive at Auschwitz and its subcamps[85][86]—about half of whom had obtained privileged positions in administration which allowed them to obtain the necessities for survival.[87]

| Date | Source | Women registered | Men registered | Murdered in gas chambers | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12–13 April | Sereď[35][34] | 443 | 634 | 1077 | These transports contained single men and women as well as childless couples.[88] | |

| 17 April | Žilina[34] | 27 | 973 | 1000 | ||

| 19 April | Žilina[34] | 536 | 46 | 1000 | ||

| 22–23 April | Poprad[23][34] | 457 | 543 | 1000 | ||

| 24 April | Žilina[34] | 558 | 442 | 1000 | ||

| 29 April | Žilina[34] | 300 | 423 | 300 | 1054 | These two transports had to be supplemented with families with children to meet the quota.[88] |

| 19–20 June | Žilina[84] | 255 | 404 | 341 | 1000 | |

| 3–4 July | Žilina[89] | 108 | 264 | 628 | 1000 | This was the first family transport to Auschwitz, the first selection ever on the ramp at Birkenau, and the first group to be murdered in Bunker II.[88][79] |

| 10–11 July | Žilina[89] | 148 | 182 | 670 | 1000 | |

| 16[89]–18 July | Žilina[89] | 178 | 327 | 459 | 1000 | |

| 24–25 July | Žilina[89] | 93 | 192 | 715 | 1000 | |

| 31 July–1 August | Žilina[89] | 75 | 165 | 608 | 848 | By 1 August, most of the Jews not exempt from deportation had already been deported or had fled to Hungary, leading to a six-week halt in the transports.[80] |

| 19 September | Žilina[81] | 71 | 206 | 723 | 1000 | The final transports targeted Jews in the labor camps, especially those who were mentally or physically disabled.[90] |

| 23 September | Žilina[81] | 67 | 294 | 639 | 1000 | |

| 20–21 October | Žilina[24][89] | 78 | 121 | 649 | 848 (or 860)[89] | |

| All information from Büchler 1996, p. 320 except source locations, from Fatran 2007, pp. 180–181. Most of it can also be verified to Czech 1997, pp. 154, 157–160, 184, 191–192, 196, 199, 203, 208, 241, 243, 256. | ||||||

Summary

Between 25 March and 20 October 1942, about 57,700[c] Jews (two-thirds of the population) were deported.[92][93] Sixty-three of the deportation trains from Slovakia were organized by Franz Novak.[94] The deportations disproportionately affected poor, rural, and Orthodox Jews; although the Šariš-Zemplín region in eastern Slovakia lost 85 to 90 percent of its Jewish population, Žilina reported that almost half of its Jews remained after the deportation.[95] The deportees were held briefly in camps in Slovakia before deportation; 26,384 from Žilina,[24] 7,500 from Patrónka,[22] 7,000 from Poprad,[23] 4,160[96] (or 4,463)[97] from Sereď, and 4,000 to 5,000 from Nováky.[98] Eighteen trains with 18,746 victims[42] went to Auschwitz, and another thirty-eight transports (with 39,000 to 40,000 deportees)[a] went to ghettos and concentration and extermination camps in the Lublin district.[100][20] Only a few hundred (estimated at 250[101] or 800[102]) survived the war.[20][103] Czech historian Daniel Putík estimates that only 1.5 percent (around 280 people) of those deported to Auschwitz in 1942 survived, while the death rate of those deported to the Lublin region approached 100 percent.[104]

Attempts by Germany and Slovak People's Party radicals to resume the transports in 1943 were unsuccessful due to the opposition of Slovak moderates and were followed by a two-year hiatus.[105][106]

1944–1945

Increasing Slovak partisan activity triggered a German invasion on 29 August 1944. The partisans responded by launching a full-scale uprising. The insurgents seized a large portion of central Slovakia but were defeated by the end of October.[107] Einsatzgruppe H, one of the SS death squads, was formed to deport or murder the estimated 25,000 Jews remaining in Slovakia.[108] Einsatzgruppe H was aided by local collaborators, including SS-Heimatschutz, Abwehrgruppe 218, and the Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions.[109][110] Most of the Jews who were exempted from the 1942 deportations lived in western Slovakia,[111] but following the invasion many fled to the mountains.[112]

Slovak historian Ivan Kamenec estimated that 13,500 Jews were deported, of whom 10,000 died,[107][113][114] but Israeli historian Gila Fatran and Czech historian Lenka Šindelářová consider that 14,150 deportees can be verified and the true figure may be higher.[115][116] Of these, between 6,734 and 7,936 were deported to Auschwitz[104] and another 5,000 to Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, Bergen-Belsen, and Theresienstadt. From Slovakia, Ravensbrück received transports totaling 1,600 women and children (mostly Jews) and 478 male prisoners, including Jews, Romani people, and political opponents. About 1,550 to 1,750 men (mostly Jews) were deported to Sachsenhausen, while about 200–300 people were deported from Sereď to Bergen-Belsen, especially Jews in mixed marriages and some intact families of Jews. Between 1,454 and 1,467 Jews were deported to Theresienstadt, especially the elderly, orphans, and women with young children.[117] About 200 or 300 Slovak political prisoners were deported to Mauthausen on 19 January and 31 March 1945.[118] Many of those deported to the concentration camps in Germany were sent onwards to satellite camps, where they worked mostly in war industries.[119] On four transports from Sereď, selections were carried out at the camp with different cars being directed to Sachsenhausen, Bergen-Belsen, Ravensbrück, and/or Theresienstadt.[117] Many details of the transports are unknown, because much of the documentation was destroyed by the perpetrators, requiring historians to rely on survivor testimonies.[120][113][121]

| Date | Source | Destination | Number of deportees | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 September | Čadca | Auschwitz | 100+ | Six men and eight women were registered at the camp. 72 males and an unknown number of females were sent to the gas chambers.[122] |

| 5 September | Čadca | Auschwitz | One man and two women were registered at the camp. An unknown number were sent to the gas chambers.[122] | |

| 20 September | Unknown | Auschwitz | 177 | From this transport, 146 people were sent to the gas chambers and the remainder were registered.[122] Israeli historian Gila Fatran estimates a total of 400 Jews were deported on the three transports.[116] |

| 30 September | Sereď | Auschwitz | 1860 | [123][124] |

| 3 October | Sereď | Auschwitz | 1836 | [125][124] |

| 10[125]–12 October[126] | Sereď | Auschwitz | 1882 or 1890 | [125][124] |

| 17[127]–19 October[128] | Sereď | Auschwitz | 862 or 920[127][124] | 113 Jewish women were registered.[128] |

| 2 November | Sereď | Auschwitz | 920 or 930 | The gas chambers of Auschwitz were used for the last time on the previous day. All of the deportees were registered at the camp without a selection.[125][129][130] |

| 2–3 November | Prešov | Ravensbrück | 364 | Mostly Jews, some Romani people.[131] According to Fatran, about 100 Jews in total were deported from Prešov.[116] |

| 9 November | Ilava | Germany | 183 | This transport included Jews but the prisoners were predominantly non-Jewish. According to a German official, another transport with 100 individuals had been dispatched from Ilava the previous week, and also sent to Germany.[122] According to Fatran, the total number of Jews deported from Ilava was about 100.[116] |

| c. 15 November | Sereď | Ravensbrück | 488 | Jews[131] |

| 16 November | Sereď | Sachsenhausen, Bergen-Belsen | 600–800 (Sachsenhausen), 100–200 (Bergen-Belsen) | Mostly Jews; there were some Mischlinge sent to Bergen-Belsen[131] |

| 28 November | Prešov | Ravensbrück | 53 | Women and children, mostly Jewish[132] |

| 2–3 December | Sereď | Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück, Theresienstadt | about 580 (Sachsenhausen), 160–200 (Ravensbrück),[132] 416[133] or 421 (Theresienstadt)[132] | Jews and several political prisoners were sent to Sachsenhausen; the transport to Ravensbrück consisted of Jewish women; those sent to Theresienstadt were exclusively Jews.[132] According to Slovak historian Katarína Hradská, the transport arrived in Theresienstadt on 23 December; 382 of those deported to Theresienstadt survived.[133] |

| c. 10 January | Kežmarok | Ravensbrück | 47 | Women and children, mostly Jews and some Romani people; also some political prisoners.[132] |

| 16 January | Sereď | Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück, Theresienstadt | 370 (Sachsenhausen), 260–310 (Ravensbrück), 127[132] or 129[133] (Theresienstadt) | Sent to Sachsenhausen were Jewish men and political prisoners; Jewish women were sent to Ravensbrück; the Jews sent to Theresienstadt were mostly those incapable of work[132] The transport arrived in Theresienstadt 19 January and 127 of the 129 deportees survived.[133] |

| 9–12 March | Sereď | Theresienstadt | 548 | According to Hradská, there were 546 survivors.[125][133] |

| 31 March–7 April | Sereď | Theresienstadt | 354 | According to Hradská, there were 352 survivors.[125][133] |

An estimated 10,000 of the deportees died.[113] The mortality rate was highest on the transports to Auschwitz in September and October, because there was a selection and most of the deportees were immediately murdered in the gas chambers. The death rate of those deported to concentration camps in Germany was around 25–50 percent. Of those deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto, however, 98 percent survived.[134] The high death rate at concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen, Bergen-Belsen and Ravensbrück was due to the exploitation of forced labor for total war and inmates were murdered based on their inability to work, rather than their race or religion. Others died during the death marches.[135] Between several hundred[107] and 2,000[116][136] Jews were killed in Slovakia, and about 10,850 survived to be liberated by the Red Army in March and April 1945.[116][137]

| Destination | Killed | Total | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auschwitz | Most | 6,734–7,936 | ||

| Bergen-Belsen | 30–50 percent | 200–300 | Very few of the children deported to Bergen-Belsen survived.[138] | |

| Ravensbrück | Less than 30 percent | About 2,000 | ||

| Sachsenhausen | At least 25 percent | 1,550–1,750 | ||

| Theresienstadt | 2 percent (40 people[133]) | 1,454–1,467 | Hradská attributes the deaths to natural causes[133] | |

| Not deported | Several hundred[107] to 2,000[116][136] | 10,850 survived[116] | ||

| All information from Putík 2015, p. 47 unless otherwise indicated. | ||||

Notes

- ^ a b Estimates include 39,006 (Katarína Hradská),[91] 39,875 (Gila Fatran), 39,883 (Yehoshua Büchler),[50] or 39,899 passengers (Laura Crago[99] and Janina Kiełboń). The exact number is unknown and impossible to determine due to discrepancies in the sources. For example, some Jews died or committed suicide before they were deported or during transport and were not counted consistently.[61]

- ^ Transports left Patrónka,[22] Poprad,[23] and Nováky in the evening,[20] and Žilina at 03:20.[24]

- ^ Estimates include 57,628[20] and 57,752.[91]

References

Citations

- ^ Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018a, p. 843.

- ^ Hutzelmann 2018, p. 19.

- ^ Paulovičová 2018, p. 5.

- ^ Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018a, pp. 843–844.

- ^ Johnson 2005, p. 316.

- ^ Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018a, pp. 843, 845–847.

- ^ a b Longerich 2010, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Büchler 1996, p. 301.

- ^ Kamenec 2007, p. 217.

- ^ a b Oschlies 2007.

- ^ Büchler 1996, p. 302.

- ^ Bauer 2002, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Büchler 1991, pp. 302–303.

- ^ a b c d Longerich 2010, p. 325.

- ^ Büchler 1996, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Bauer 1994, p. 66.

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 777.

- ^ a b c Ward 2013, p. 230.

- ^ a b c d e f Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018a, p. 847.

- ^ a b Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018c, p. 874.

- ^ a b c Rajcan 2018b, p. 855.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rajcan 2018d, p. 879.

- ^ a b c Rajcan 2018f, p. 889.

- ^ Hutzelmann 2018, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Silberklang 2013, p. 294.

- ^ a b Ghert-Zand 2020.

- ^ a b Büchler 1996, p. 304.

- ^ Büchler 1996, pp. 304–305.

- ^ a b c Büchler 1996, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Büchler 1996, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Büchler 1991, p. 166.

- ^ Czech 1997, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fatran 2007, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018e, p. 881.

- ^ Büchler 1996, pp. 305, 320.

- ^ Czech 1997, p. 152.

- ^ Czech 1997, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Longerich 2010, pp. 325–326.

- ^ a b Kamenec 2007, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Silberklang 2013, p. 295.

- ^ a b Hilberg 2003, p. 785.

- ^ Silberklang 2013, pp. 299, 301.

- ^ a b Büchler 1991, pp. 159, 166.

- ^ Sokolovič 2013, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Kamenec 2011b, p. 107.

- ^ Sokolovič 2013, p. 347.

- ^ Nižňanský 2014, p. 66.

- ^ Paulovičová 2012, p. 305.

- ^ a b Silberklang 2013, p. 296.

- ^ Büchler 1991, pp. 159, 161.

- ^ Büchler 1991, p. 160.

- ^ Büchler 1991, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Büchler 1991, p. 159.

- ^ Büchler 1991, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Kamenec 2007, p. 222.

- ^ a b c d Kuwałek 2012g, p. 673.

- ^ Kuwałek 2012g, pp. 673–674.

- ^ a b c d e f Dean 2012, p. 704.

- ^ a b c Crago & White 2012, p. 689.

- ^ a b Silberklang 2013, pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b Crago 2012h, p. 679.

- ^ Crago 2012h, pp. 680–681.

- ^ Crago 2012i, p. 684.

- ^ a b c Crago 2012b, p. 624.

- ^ a b c d Crago 2012c, p. 638.

- ^ Farkash 2014, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f Crago 2012e, p. 655.

- ^ Crago 2012e, pp. 655–656.

- ^ Dean 2012, pp. 704–705.

- ^ Büchler 1991, p. 158.

- ^ Yad Vashem 2009, p. 552.

- ^ a b c Kuwałek & Dean 2012, p. 641.

- ^ Kuwałek & Dean 2012, pp. 640–642.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 325–326, 358.

- ^ Silberklang 2013, pp. 296, 301–302.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b Büchler 1996, p. 313.

- ^ a b Longerich 2010, pp. 326, 345.

- ^ a b Bauer 1994, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Kamenec 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Büchler 1996, p. 309.

- ^ Büchler 1996, pp. 313–314.

- ^ a b Friling 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Hutzelmann 2018, p. 34.

- ^ Büchler 1996, pp. 309, 322.

- ^ Büchler 1996, p. 316.

- ^ a b c Büchler 1996, p. 307.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fatran 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Fatran 1994, p. 171.

- ^ a b Hradská 1996, p. 82.

- ^ Bauer 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Kamenec 2011a, p. 189.

- ^ Browning 2007, p. 381.

- ^ Ward 2002, p. 584.

- ^ Danko 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018e, p. 882.

- ^ Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018c, p. 876.

- ^ Crago 2012a, p. 608.

- ^ Büchler 1991, p. 151.

- ^ Rothkirchen 2001, p. 598.

- ^ Ward 2013, p. 235.

- ^ Kamenec 2002, p. 130.

- ^ a b Putík 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018a, p. 848.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 404–405.

- ^ a b c d Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018a, p. 849.

- ^ Fatran 1996, pp. 99, 101.

- ^ Fatran 1996, p. 101.

- ^ Putík 2015, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Hradská 1996, p. 90.

- ^ Fatran 1996, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Kamenec 2007, p. 337.

- ^ Ward 2002, p. 589.

- ^ Šindelářová 2013, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fatran 1996, p. 119.

- ^ a b Putík 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Putík 2015, pp. 45, 47.

- ^ Putík 2015, p. 199.

- ^ Fatran 1996, p. 116.

- ^ Putík 2015, pp. 197, 212.

- ^ a b c d Fatran 1996, p. 117.

- ^ Fatran 1996, pp. 108, 118.

- ^ a b c d Hradská 1996, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d e f Fatran 1996, p. 118.

- ^ Czech 1997, p. 730.

- ^ a b Fatran 1996, pp. 112, 118.

- ^ a b Czech 1997, p. 735.

- ^ Putík 2015, pp. 55, 197–198.

- ^ Czech 1997, pp. 743–744.

- ^ a b c Putík 2015, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f g Putík 2015, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hradská 1996, p. 93.

- ^ Putík 2015, pp. 47, 212.

- ^ Putík 2015, pp. 209–210.

- ^ a b Ward 2013, p. 253.

- ^ Kamenec 2007, p. 341.

- ^ Putík 2015, p. 200.

General sources

Books

- Bauer, Yehuda (1994). Jews for Sale?: Nazi-Jewish Negotiations, 1933–1945. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05913-7.

- Bauer, Yehuda (2002). Rethinking the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09300-1.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2007). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939–March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0392-1.

- Czech, Danuta (1997). Auschwitz Chronicle, 1939–1945. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-5238-1.

- Fatran, Gila (2007). Boj o prežitie [The Struggle for Survival] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Múzeum židovskej kultúry. ISBN 978-80-8060-206-2.

- Friling, Tuvia (2006). "Istanbul 1942-1945: The Kollek-Avriel and Berman-Ofner Networks". Secret Intelligence and the Holocaust: Collected Essays from the Colloquium at the City University of New York Graduate Center. New York: Enigma Books. pp. 105–156. ISBN 978-1-929631-60-5.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003) [1961]. The Destruction of the European Jews. Vol. 2 (3 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09592-0.

- Hutzelmann, Barbara (2018). "Einführung: Slowakei" [Introduction: Slovakia]. In Hutzelmann, Barbara; Hausleitner, Mariana; Hazan, Souzana (eds.). Slowakei, Rumänien und Bulgarien [Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria]. Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933–1945 [The Persecution and Murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany 1933-1945] (in German). Vol. 13. Munich: De Gruyter. pp. 18–45. ISBN 978-3-11-036500-9.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2002) [1992]. "The Deportation of Jewish Citizens from Slovakia in 1942". In Długoborski, Wacław; Tóth, Dezider; Teresa, Świebocka; Mensfelt, Jarek (eds.). The Tragedy of the Jews of Slovakia 1938–1945: Slovakia and the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question". Translated by Mensfeld, Jarek. Oświęcim and Banská Bystrica: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising. pp. 111–139. ISBN 978-83-88526-15-2.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2007) [1991]. On the Trail of Tragedy: The Holocaust in Slovakia. Translated by Styan, Martin. Bratislava: Hajko & Hajková. ISBN 978-80-88700-68-5.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2011). "The Slovak state, 1939–1945". In Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (eds.). Slovakia in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–192. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511780141. ISBN 978-1-139-49494-6.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Rothkirchen, Livia (2001). "Slovakia". In Laqueur, Walter; Baumel, Judith Tydor (eds.). Holocaust Encyclopedia. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 595–600. ISBN 978-0-300-08432-0.

- Silberklang, David (2013). Gates of Tears: the Holocaust in the Lublin District. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. ISBN 978-965-308-464-3.

- Šindelářová, Lenka (2013). Finale der Vernichtung: die Einsatzgruppe H in der Slowakei 1944/1945 (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-73733-8.

- Sokolovič, Peter (2013). Hlinkova Garda 1938 – 1945 [Hlinka Guard 1938 – 1945] (PDF) (in Slovak). Bratislava: National Memory Institute. ISBN 978-80-89335-10-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Ward, James Mace (2013). Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist Slovakia. Ithaka: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6812-4.

- Miron, Gai; Shulhani, Shlomit, eds. (2009). "Opole". The Yad Vashem Encyclopedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust. Vol. 2. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 550–552. ISBN 978-965-308-345-5.

Journals

- Büchler, Yehoshua (1991). "The deportation of Slovakian Jews to the Lublin District of Poland in 1942". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 6 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1093/hgs/6.2.151. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Büchler, Yehoshua (1996). "First in the Vale of Affliction: Slovakian Jewish Women in Auschwitz, 1942". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 10 (3): 299–325. doi:10.1093/hgs/10.3.299. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Danko, Marek (2010). "Internačné zariadenia v Slovenskej republike (1939–1945) so zreteľom na pracovné útvary" [Internment camps in Slovak republic (1939–1945) with emphasis on labor units] (PDF). Človek a Spoločnosť (in Slovak). 13 (1): 1–14. ISSN 1335-3608. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Farkash, Talia (2014). "Labor and Extermination: The Labor Camp at the Dęblin–Irena Airfield Puławy County, Lublin Province, Poland – 1942–1944". Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust. 29 (1): 58–79. doi:10.1080/23256249.2014.987989. S2CID 130815153.

- Fatran, Gila (1994). "The "Working Group"". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 8 (2). Translated by Greenwood, Naftali: 164–201. doi:10.1093/hgs/8.2.164. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Fatran, Gila (1996). "Die Deportation der Juden aus der Slowakei 1944–1945" [The deportation of the Jews from Slovakia 1944–45]. Bohemia: Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kultur der Böhmischen Länder (in German) (37): 98–119. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Hradská, Katarína (1996). "Vorgeschichte der slowakischen Transporte nach Theresienstadt" [The History of Slovak Transports to Theresienstadt]. Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente (in German) (3). Translated by Hennerová, Magdalena: 82–97. CEEOL 274407.

- Johnson, Owen V. (2005). "Židovská komunita na Slovensku medzi ceskoslovenskou parlamentnou demokraciou a slovenským štátom v stredoeurópskom kontexte, Eduard Nižnanský (Prešov, Slovakia: Universum, 1999), 292 pp., 200 crowns (Slovak)". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 19 (2): 314–317. doi:10.1093/hgs/dci033.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2011). "Fenomén korupcie v procese tzv. riešenia "židovskej otázky" na Slovensku v rokoch 1938–1945" [The phenomenon of corruption in the so-called solutions to the "Jewish questions" in Slovakia between 1938 and 1945]. Forum Historiae (in Slovak). 5 (2): 96–112. ISSN 1337-6861. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Nižňanský, Eduard (2014). "On Relations between the Slovak Majority and Jewish Minority During World War II". Yad Vashem Studies. 42 (2): 47–90. ISSN 0084-3296.

- Paulovičová, Nina (2018). "Holocaust Memory and Antisemitism in Slovakia: The Postwar Era to the Present". Antisemitism Studies. 2 (1). Indiana University Press: 4–34. doi:10.2979/antistud.2.1.02. S2CID 165383570.

- Ward, James Mace (2002). ""People Who Deserve It": Jozef Tiso and the Presidential Exemption". Nationalities Papers. 30 (4): 571–601. doi:10.1080/00905992.2002.10540508. ISSN 1465-3923. S2CID 154244279.

Theses

- Paulovičová, Nina (2012). Rescue of Jews in the Slovak State (1939–1945) (PhD thesis). Edmonton: University of Alberta. doi:10.7939/R33H33. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Putík, Daniel (2015). Slovenští Židé v Terezíně, Sachsenhausenu, Ravensbrücku a Bergen-Belsenu, 1944/1945 [Slovak Jews in Theresienstadt, Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen, 1944/1945] (PhD thesis) (in Czech). Prague: Charles University. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2019. English-language abstract pp. 203–216.

Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos

Volume 2—open access Archived 9 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Crago, Laura (2012a). "Lublin Region (Distrikt Lublin)". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 604–609. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura (2012b). "Chełm". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 623–626. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura (2012c). "Irena (Dęblin–Irena)". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 636–639. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Kuwałek, Robert; Dean, Martin (2012). "Izbica". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 639–643. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura (2012e). "Końskowola". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 654–657. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Kuwałek, Robert (2012g). "Lubartów". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 672–674. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura (2012h). "Łuków". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 678–682. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura (2012i). "Miedzyrzec Podlaski". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 684–688. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura; White, Joseph Robert (2012). "Opole". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 688–691. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Dean, Martin (2012). "Rejowiec". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 703–705. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

Volume 3

- Rajcan, Vanda; Vadkerty, Madeline; Hlavinka, Ján (2018a). "Slovakia". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R.; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Vol. 3. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 842–852. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.

- Rajcan, Vanda (2018b). "Bratislava/Patrónka". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R.; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Vol. 3. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 854–855. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.

- Nižňanský, Eduard; Rajcan, Vanda; Hlavinka, Ján (2018c). "Nováky". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R.; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Vol. 3. Translated by Kramarikova, Marianna. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 874–877. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.

- Rajcan, Vanda (2018d). "Poprad". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R.; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Vol. 3. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 878–880. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.

- Nižňanský, Eduard; Rajcan, Vanda; Hlavinka, Ján (2018e). "Sereď". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R.; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Vol. 3. Translated by Kramarikova, Marianna. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 881–883. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.

- Rajcan, Vanda (2018f). "Žilina". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R.; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Vol. 3. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 889–890. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.

Web

- Ghert-Zand, Renee (2 January 2020). "First transport of Jews to Auschwitz was 997 young Slovak women and teens". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Oschlies, Wolf [de] (12 April 2007). "Aktion David — Deportation von 60.000 slowakischen Juden" [Aktion David—Deportation of 60,000 Slovak Jews]. Zukunft braucht Erinnerung [Future needs Memory] (in German). Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Macadam, Heather Dune (2019). 999: The Extraordinary Young Women of the First Official Jewish Transport to Auschwitz. New York: Kensington Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8065-3936-2.

External links

- Cuprik, Roman (27 March 2017). "We were joking before the trip, women from the first transport to Auschwitz recall". The Slovak Spectator. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- List of Slovak Jews deported to Lublin District ghettos Archived 29 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine