Early life of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith (December 23, 1805 – June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement whose current followers include members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Community of Christ, and other Latter Day Saint denominations. The early life of Joseph Smith covers his life from his birth to the end of 1827.

Smith was born in Sharon, Vermont, the fifth of eleven children born to Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith. By 1817, Smith's family had moved to the "burned-over district" of western New York, an area repeatedly swept by religious revivals during the Second Great Awakening. Smith family members held divergent views about organized religion, believed in visions and prophecies, and engaged in certain folk religious practices typical of the era. Smith briefly investigated Methodism, but he was generally disillusioned with the churches of his day.

Around 1820 Smith is said to have experienced a theophany, now known as his First Vision among adherents. Around this time he, along with other male members of his family, was hired to assist in searching for buried treasure. In 1823, Smith said an angel directed him to a nearby hill where he said was buried a book of golden plates containing a Christian history of ancient American civilizations. According to Smith, the angel prevented him from taking the plates in 1823, telling him to come back in exactly a year. Smith made annual visits to the hill over the next three years, reporting to his family that he had not yet been allowed to take the plates.

Meanwhile, during one of Smith's treasure hunting expeditions, he met and fell in love with Emma Smith from Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, whom he married in 1827. Returning with Emma to the hill in 1827, Smith said the angel allowed him to take the plates but forbade him from showing them to anyone except those to whom the angel directed. As news of the plates spread, Smith's former treasure hunting associates sought to share in the proceeds, ransacking places they thought the plates were hidden. Intending to translate the plates himself, Smith moved to Harmony Township to live with his in-laws.

Childhood

Smith was born in Sharon, Vermont, the fifth of eleven children born to Joseph Smith Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith. Through modern DNA testing of Smith's relatives, it's likely that the Smith family were of Irish descent originally. Smith carried the Y-DNA marker R-M222, a subclade of Haplogroup R1b found almost entirely in people of Northwestern Irish descent today.[1][2]

The Smiths were a middling farm family, but suffered a fateful loss when Smith Sr., after speculating in ginseng and being cheated by a business associate, was financially ruined. After he sold the family farm to pay his debts, the Smiths "crossed the boundary dividing independent ownership from tenancy and day labor." In the next fourteen years, the Smiths moved seven times.[3]

Despite the moves and the financial woes, Lucy Smith remembered the period of Joseph Smith's early childhood as "perfectly comfortable both for food and raiment as well as that which is necessary to a respectable appearance in society."[4] Then during the winter of 1812–1813, typhoid fever struck along the Connecticut Valley, including the area around Lebanon, New Hampshire, where the Smiths had recently moved. A number of family members fell ill, and Joseph experienced a common complication whereby typhoid bacteria infected bone, in Smith's case, the shin bone. Lucy later claimed that she had refused to permit her son's leg to be amputated; in fact, the Smiths had chanced on one of New England's most respected physicians, Nathan Smith, who "probably alone in American medicine at this time" advocated removal of the dead portion of the bone rather than amputation of the leg. After the typically horrific early nineteenth-century surgery without either anesthetic or antiseptic, Smith eventually recovered, though he used crutches for several years and had a slight limp for the remainder of his life.[5][6]

In 1814 the Smiths moved back across the Connecticut River to Norwich, Vermont, where they suffered three seasons of crop failures, the last the result of the Year Without a Summer.[7] The extended Smith clan had already moved west to New York, and in 1817, Joseph Smith Sr. traveled alone to Palmyra, New York, followed shortly by the rest of his family—although not before Lucy Smith was forced to settle with some last-minute creditors.[8] In Palmyra village, Smith Sr. and his oldest sons hired themselves out as common laborers, ran a "cake and beer shop," and peddled refreshments from a cart; Lucy painted cloth coverings for tables and stands.[9] When Smith was fourteen, he was apparently shot at, while returning home from an errand, but was not injured. The bullet missed him, hitting a cow instead, and the perpetrator was not found.[10] In 1820, the family contracted to pay for a 100-acre (40 ha) farm just outside Palmyra in Manchester Township.[11] The Smith family first built a log home,[12] then in 1822, under the supervision of Joseph Smith's oldest brother Alvin, they began building a larger frame house.[13] Alvin died in November 1823, possibly as a result of being given calomel for "bilious fever", and the house remained uncompleted for a year.[14] By this time Joseph Smith Sr. may have partially abdicated family leadership to Alvin,[15] and in 1825, the Smiths were unable to make their mortgage payments. When their creditor foreclosed, the family persuaded a local Quaker, Lemuel Durfee, to buy the farm and rent it to them. Nevertheless, in 1829, the Smiths and five of their children moved back into the log house, with Hyrum Smith and his wife.[16]

Joseph Smith had little formal schooling, but may have attended school briefly in Palmyra and received instruction in his home.[17] Young Joseph worked on his family farm and perhaps took an occasional odd job or worked for nearby farmers.[18] His mother described him as "much less inclined to the perusal of books than any of the rest of the children, but far more given to meditation and deep study." Lucy Smith also noted that though he never read through the Bible until he was at least eighteen, he was imaginative and could regale the family with "the most amusing recitals" of the life and religion of ancient Native Americans "with as much ease, seemingly, as if he had spent his whole life with them."[19] Smith was variously described as "remarkably quiet,"[20] "taciturn," "proverbially good-natured," and "never known to laugh."[21] One acquaintance said Smith had "a jovial, easy, don't-care way about him," and he had an aptitude for debating moral and political issues in a local junior debating club.[22] Biographer Fawn Brodie wrote, "He was a gregarious, cheerful, imaginative youth, born to leadership, but hampered by meager education and grinding poverty."[23]

Religious background

Smith grew to maturity during the Second Great Awakening, a period of religious excitement in the United States. New York west of the Catskill and Adirondack Mountains became known as the "Burned-over district" because it was "repeatedly singed by the fires of revival that swept through the region in the early years of the nineteenth century."[24] Major multi-denominational religious revivals occurred in the Palmyra area in both 1816-17 (when the Smiths were in the process of migrating from Vermont) and in 1824-25.[25] Small denominational revivals and camp meetings occurred during the intervals.[26][27][28]

Joseph Smith's ancestors had an eclectic variety of religious views and affiliations.[29] For instance, Joseph Smith's paternal grandfather, Asael, was a Universalist who opposed evangelical religion. According to Lucy Smith, Asael once came to Joseph Smith Sr.'s door after he had attended a Methodist meeting with Lucy and "threw Tom Paine's Age of Reason into the house and angrily bade him read that until he believed it."[30] Conversely, in 1811 Smith's maternal grandfather, Solomon Mack, self-published a book describing a series of heavenly visions and voices he said had led to his conversion to Christianity at the age of seventy-six.[31]

Smith's parents also experienced visions. Before Joseph was born, his mother Lucy, prayed in a grove about her husband's refusal to attend church and later said she had had a dream-vision, which she interpreted as a prophecy that Joseph Sr. would later accept the "pure and undefiled Gospel of the Son of God."[32] According to Lucy, Joseph Smith Sr. also had seven visions between 1811 and 1819, coming at a time when he was "much excited upon the subject of religion." These visions confirmed in his mind the correctness of his refusal to join any organized church and led him to believe that he would be directed in the proper path toward salvation.[33] Lucy's account, recorded thirty years after the period in which the visions are said to have occurred, suggests "a tendency to make her husband the predecessor of her son" by echoing passages in the Book of Mormon.[34]

Like perhaps thousands of contemporary Americans,[35] the Smith family practiced various forms of folk magic such as using divining rods and seer stones to search for buried treasure. Four witnesses reported that the Smiths used divining rods in the Palmyra area, and sometime between Joseph Smith's eleventh and thirteenth years, he began "following his father's example in using a divining rod."[36] Magical parchments handed down in the Hyrum Smith family may have belonged to Joseph Sr.[37] Lucy Mack Smith noted in her memoirs that while family members were "trying to win the faculty of Abrac, drawing magic circles or sooth saying," they did not neglect manual labor, "but whilst we worked with our hands we endeavored to remember the service of & the welfare of our souls."[38] Smith's reputation among his Palmyra neighbors was that of a "nondescript farm boy" who was "lazy and superstitious," and townspeople viewed his family as "treasure-seekers, not eager Christians."[39] Thus, Smith was reared in a family that believed in prophecy and visions, was skeptical of organized religion, and was interested in both folk magic and new religious ideas.[40]

Smith said he had become concerned about religion "at about the age of twelve years," although later he seems to have wondered whether "a Supreme being did exist."[41] Smith apparently attended the Presbyterian Sunday school as a child,[42] and later as an adolescent, he displayed interest in Methodism.[43] One of Smith's acquaintances said that Smith had caught "a spark of Methodism" at camp meetings "away down in the woods, on the Vienna road."[44] He even reportedly spoke during some of these meetings, and the acquaintance described Smith as a "very passable exhorter."[45]

Nevertheless, at some point after 1822,[46] Smith withdrew from organized religion.[47] According to his mother, Smith claimed, "I can take my Bible, and go into the woods, and learn more in two hours, than you can learn at meeting in two years, if you should go all the time."[48] Still, Smith seems to have been significantly influenced by the interdenominational revival of 1824-25.[49]

First Vision

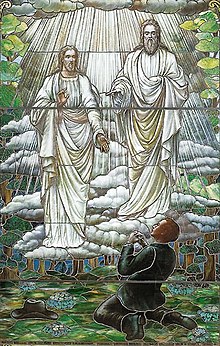

Like his father, the younger Smith reportedly had his own set of visions, the first of which occurred in the early 1820s when Smith was in his early teens and is called by Latter Day Saints the First Vision.[50] The first description of this event was not published until 1832,[51] which said the event occurred in 1821;[52] however, most accounts date the event to the year 1820.[53] Latter Day Saints believe that the First Vision was a theophany (a personal and direct communication from God). The details of the theophany have varied as the story was retold throughout Smith's life.[54]

According to accounts by Joseph and his brother, William, the First Vision was prompted in part by a reading of James 1:5, which in the King James Version reads, "If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, who giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not, and it shall be given him"; William suggested that Smith "ask of God".[55] William also suggested that much of the "religious excitement" in the area was caused by the Rev. George Lane, a "great revival preacher".[56] Lane is never recorded as having visited Palmyra until 1824, although he visited nearby Vienna in 1819 for a large Methodist conference.[57] Joseph and his family could have traveled to sell cake and beer at this event, as they did other events in the Palmyra vicinity, but this is pure speculation.[58]

The exact details of the First Vision vary somewhat depending upon who is recounting the story and when. Smith's first account in 1832 dated the vision to 1821 and stated that he saw "a piller [sic] of fire light above the brightness of the sun at noon day", and that "the Lord opened the heavens upon me and I saw the Lord and he spake unto me saying Joseph my son thy sins are forgiven thee".[52] Whether Smith regarded this event as a vision or as an actual visitation by a physical being has been debated, because a missionary tract published for Smith's church in 1840 stated that after Smith saw the light, "his mind was caught away, from the natural objects with which he was surrounded; and he was enwrapped in a heavenly vision".[59]

In an account Smith dictated in 1838 for inclusion in the official church history, he described the First Vision as an appearance of two divine personages sometime during the spring of 1820:

"I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head, above the brightness of the sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me…When the light rested upon me I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. One of them spake unto me, calling me by name, and said, pointing to the other, 'This is my Beloved Son. Hear Him!'".[60]

It is unclear who, if anyone, Smith told about his vision prior to his reported discovery of the golden plates in 1823.[61] According to Smith, he told his mother at the time that he had "learned for [him]self that Presbyterianism is not true";[62] however, mention of this conversation is omitted from Lucy's own history,[63] and Joseph never stated that he described the details of the vision to his family in 1820 or soon thereafter. He did say that he spoke about the vision with "one of the Methodist preachers,[64] who was very active in the before-mentioned religious excitement".[65] Many have presumed this to be the Rev. Lane, but there is no record of Lane visiting the Palmyra vicinity in 1820.[66] Joseph's brother William was apparently unaware of any visions until 1823,[67] although he would have only been nine years old in 1820.

Smith stated that the retelling of his vision story "excited a great deal of prejudice against me among professors of religion, and was the cause of great persecution, which continued to increase".[65] Tales of visions and theophanies, however, were not unusual at the time, though the clergy of many organized religions often resisted the stories.[68][69] Early prejudice against Smith may have taken place by clergy, but there is no contemporary record of this.[original research?] The bulk of Smith's persecution seems to have arisen among laity, and not because of his First Vision, but because of his later assertion to have discovered the golden plates in a hill near his home;[citation needed] the statement was widely publicized and ridiculed in local newspapers beginning around 1827.[citation needed]

Years later, one non-Mormon neighbor summed up views of Smith and his family by their Palmyra neighbors by saying, "To tell the truth, there was something about him they could not understand; some way he knew more than they did, and it made them mad."[70]

Treasure hunting

From about 1819, Smith regularly practiced scrying, a form of divination in which a "seer" looked into a seer stone to receive supernatural knowledge.[71] Smith usually practiced crystal gazing by putting a stone at the bottom of a white stovepipe hat, putting his face over the hat to block the light, then divining information from the stone.[72] Smith and his father achieved "something of a mysterious local reputation in the profession—mysterious because there is no record that they ever found anything despite the readiness of some local residents to pay for their efforts."[73]

In late 1825, Josiah Stowell, a well-to-do farmer from South Bainbridge, Chenango County, New York, who had been searching for a lost Spanish mine near Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania with another seer, traveled to Manchester to hire Smith "on account of having heard that he possessed certain keys, by which he could discern things invisible to the natural eye."[74]

Smith agreed to take the job of assisting Stowell and Hale, and he and his father worked with the Stowell-Hale team for approximately one month, attempting, according to their contract, to locate "a valuable mine of either Gold or Silver and also...coined money and bars or ingots of Gold or Silver".[75] Smith boarded with an Isaac Hale (a relative of William Hale), and fell in love with Isaac Hale's daughter Emma, a schoolteacher he would later marry in 1827. Isaac Hale, however, disapproved of their relationship and of Smith in general. According to an unsupported account by Hale, Smith attempted to locate the mine by burying his face in a hat containing the seer stone; however, as the treasure hunters got close to their objective, Smith said that an enchantment became so strong that Smith could no longer see it.[76] The failed project disbanded on November 17, 1825.[77]

In 1826 Smith was arrested and brought to court in Bainbridge, New York, on the complaint of Stowell's nephew who accused Smith of being "a disorderly person and an imposter."[78] Court records show that Smith, identified as "The Glass Looker," stood before the court on March 20, 1826, on a warrant for an unspecified misdemeanor charge,[79] and that the judge issued a mittimus for Smith to be held, either during or after the proceedings.[citation needed] Although Smith's associate Oliver Cowdery later stated that Smith was "honorably acquitted,"[80] the result of the proceeding is unclear, with some claiming he was found guilty, others claiming he was "condemned" but "designedly allowed to escape," and yet others (including the trial note taker) claiming he was "discharged" for lack of evidence.[citation needed]

By November 1826, Josiah Stowell could no longer afford to continue searching for buried treasure; Smith traveled to Colesville, New York, for a few months to work for Joseph Knight Sr.,[citation needed] one of Stowell's friends. There are reports that Smith directed further excavations on Knight's property and at other locations around Colesville.[81] Smith later commented on his working as a treasure hunter: "'Was not Joseph Smith a money digger?' Yes, but it was never a very profitable job for him, as he only got fourteen dollars a month for it."[82]

Marriage to Emma Hale

Because Smith had been unable to gain Isaac Hale's approval, he and Emma Hale Smith eloped to South Bainbridge on January 18, 1827, after which Joseph and Emma went to live with Smith's parents in Manchester, New York.[83]

Moroni and the golden plates

While Smith was working as a treasure hunter, he was also frequently occupied with another more religious matter: acquiring a set of golden plates he said were deposited, along with other artifacts, in a prominent hill near his home.

In Smith's own account dated 1838, he stated that an angel visited him on the night of September 21, 1823.[84] Concerning the visit, Smith dictated the following:

He called me by name, and said unto me that he was a messenger sent from the presence of God to me, and that his name was Moroni;[85] that God had a work for me to do; and that my name should be had for good and evil among all nations, kindreds, and tongues, or that it should be both good and evil spoken of among all people.

He said there was a book deposited, written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent, and the source from whence they sprang. He also said that the fulness[sic] of the everlasting Gospel was contained in it, as delivered by the Savior to the ancient inhabitants; also that there were two stones in silver bows—and these stones, fastened to a breastplate, constituted what is called the Urim and Thummim—deposited with the plates".[citation needed]

The term 'Urim and Thummim' was not initially used by Smith and his associates prior to around 1832, instead referring to the device as 'interpreters' or 'spectacles'.[86] The words Urim and Thummim derive from passages in the Old Testament which describe the use of "the Urim and the Thummim" as a means for divination by Israelite priests (see, e.g., Exodus 28:30).

After the messenger departed, Smith said he had two more encounters with him that night and an additional one the next morning, after which he told his father[87] and soon thereafter the rest of his family, who believed his story, but generally kept it within the family.[88]

Thus, on September 22, 1823, a day listed in local almanacs as the autumn equinox, Smith said that he went to a prominent hill near his home, and found the location of the artifacts.[89] There are varying accounts as to how Smith reportedly found the precise location of the golden plates. In 1838, Smith stated that this location was shown to him in a vision while he conversed with Moroni.[90] This conforms to an account by Smith's friend Joseph Knight Sr., though he refers to Smith's guide only as "the personage."[91] However, according to a Palmyra resident Henry Harris, Smith told him he located the plates using his seer stone.[92] In yet another account, the angel required Smith to follow a sequence of landmarks until he arrived at the correct location.[93]

The plates, according to Smith, were inside a covered stone box. However, Smith stated he was unable to obtain the plates at his first visit. According to an account by Willard Chase, the angel gave Smith a strict set of "commandments" which he was to follow in order to obtain the plates. Among these requirements, according to Chase, was that Smith must approach the site "dressed in black clothes, and riding a black horse with a switch tail, and demand the book in a certain name, and after obtaining it, he must go directly away, and neither lay it down nor look behind him".[94] Smith's close friend Joseph Knight Sr. corroborates the requirement that Smith was to "take the Book and go right away".[91] According to Smith's mother, the angel forbade him to put the plates on the ground until they were under lock and key.[95] He was, however, according to a retelling of an account by Smith Sr., allowed to put down the plates on a napkin he was to bring with him for that purpose.[96]

When Smith arrived at the place where the plates were supposed to be, he reportedly took the plates from the stone box they were in and set them down on the ground nearby, looking to see if there were other items in the box that would "be of some pecuniary advantage to him".[97] When he turned around, however, the plates were said to have disappeared into the box, which was then closed.[91] When Smith attempted to get the plates back out of the box, the angel hurled him back to the ground with a violent force (id.).[98] After three failed attempts to retrieve the plates, the angel told him that he could not have them then, because he "had been tempted of the advisary [sic] and saught [sic] the Plates to obtain riches and kept not the commandments that I should have".[52]

Thus, Smith said the angel directed him to return the next year on September 22, 1824, with the "right person", whom the angel reportedly said was his brother Alvin.[91] However, Alvin died within a few months, and when Smith returned to the hill in 1824, he did not return with the plates. Once again, the angel reportedly told Smith that he must return the next year with the "right person", the identity of whom the angel would not say.[91] According to Smith's associate Willard Chase, Smith originally thought this person was to be Samuel Tyler Lawrence, a "seer" himself who worked in Smith's treasure-seeking company in Palmyra,[99] and therefore Smith reportedly took Lawrence to the hill in 1825.[100] At Lawrence's prompting, Smith reportedly ascertained through his seer stone that there was an additional item together with the plates in the box, which Smith later called the Urim and Thummim.[101] However, Lawrence was apparently not the "right person", because Smith did not obtain the plates in his 1825 visit.

Later, Smith reportedly determined by looking into his seer stone that the "right person" was Emma Hale Smith, his future wife.[91] There is no specific record of Smith seeing the angel in 1826, however, after Joseph and Emma were married on January 18, 1827, Smith returned to Manchester, and as he passed by Cumorah, he said he was chastised by the angel for not being "engaged enough in the work of the Lord".[102] He was reportedly told that the next annual meeting was his last chance to get the plates and the Urim and Thummim.[103]

Just days prior to the day Smith said he was to meet with the angel on September 22, 1827, Smith's treasure-seeking associate, Josiah Stowell, and Joseph Knight Sr. arranged to be in Palmyra for the attempt to retrieve the plates.[104] Because Smith was concerned that Samuel Lawrence, his earlier confidant, might interfere, Smith sent his father to spy on Lawrence's house the night of September 21 until dark.[103] Late that night, Smith took the horse and carriage of Joseph Knight Sr. to Cumorah with his wife Emma.[105] Leaving Emma in the wagon, where she knelt in prayer,[106] he reportedly walked to the site of the golden plates, retrieved them, and hid them in a fallen tree-top on or near the hill.[107] He also reportedly retrieved the Urim and Thummim, which he showed to his mother the next morning.[108] According to Knight, Smith was more fascinated by this artifact than he was the plates.[103]

Over the next few days, Smith took a well-digging job in nearby Macedon to obtain money to buy a solid lockable chest in which he said he would put the plates.[108] By then, however, some of Smith's treasure-seeking company had heard that Smith was successful in obtaining the plates, and they wanted what they believed was their cut of the profits from what they saw as part of their joint venture.[109] Spying once again on the house of Samuel Lawrence, Smith Sr. determined that a group of ten–twelve of these men, including Lawrence and Willard Chase, had enlisted the talents of a renowned and supposedly talented seer from 60 miles (100 km) away, in an effort to locate where the plates were hidden by means of divination.[110] When Emma heard of this, she went to Macedon and informed Smith Jr., who reportedly determined through his Urim and Thummim that the plates were safe, but nevertheless he hurriedly traveled home by horseback.[111] Once home in Palmyra, he then walked to Cumorah and said he removed the plates from their hiding place, and walked back home with the plates wrapped in a linen frock under his arm, suffering a dislocated thumb as he fended off attackers.[112]

According to Smith, the plates "had the appearance of gold", and were:

six inches wide and eight inches long and not quite so thick as common tin. They were filled with engravings, in Ancient Egyptian characters and bound together in a volume, as the leaves of a book with three rings running through the whole. The volume was something near six inches in thickness, a part of which was sealed. The characters on the unsealed part were small, and beautifully engraved. The whole book exhibited many marks of antiquity in its construction and much skill in the art of engraving.[113]

Smith refused to allow anyone, including his family, to view the plates directly. Some people, however, were allowed to heft them or feel them through a cloth.[114] At first, he reportedly kept the plates in a chest under the hearth in his parents' home.[115] Fearing it might be discovered, however, Smith hid the chest under the floor boards of his parents' old log home nearby.[109] Later, he said he took the plates out of the chest, left the empty chest under the floor boards, and hid the plates in a barrel of flax, not long before the location of the empty box was discovered and the place ransacked by Smith's former treasure-seeking associates, who had enlisted one of the men's sisters to find that location by looking in her seer stone.[116]

Move to Harmony Township, Pennsylvania

Joseph Smith's intention was to keep the box reportedly containing the golden plates safe from his Palmyra neighbors while he dictated a translation of the book's reputed contents, which he would then publish. To do so, however, he needed an investment of money, and at the time he was penniless.[115] Therefore, Smith sent his mother[117] to the home of Martin Harris, a local landowner said at the time to be worth about $8,000 to $10,000.[118]

Harris had apparently been a close confidant of the Smith family since at least 1826,[119] and he may have heard about Smith's attempts to obtain the plates from the angel even earlier from Smith Sr.[120] He was also a believer in Smith's powers with his seer stone.[99] When Lucy visited Harris, he had heard about Smith's report to have found golden plates through the grapevine in Palmyra, and was interested in finding out more.[121] Thus, at Lucy Smith's request, Harris went to the Smith home, heard the story from Smith, and hefted a glass box that Smith said contained the plates.[122] Smith convinced Harris that he had the plates, and that the angel had told him to "quit the company of the money-diggers".[123] Convinced, Harris immediately gave Smith $50 (equivalent to $1,300 in 2023), and committed to sponsor the translation of the plates.[124]

The money provided by Harris was enough to pay all of Smith's debts in Palmyra, and for him to travel with Emma and all of their belongings to Harmony Township, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, where they would be able to avoid the public commotion in Palmyra over the plates.[125] Thus, in early October 1827, they moved to Harmony, with the glass box reportedly holding the plates hidden during the trip in a barrel of beans.[125]

Notes

- ^ Groote, Michael De (2008-08-08). "DNA shows Joseph Smith was Irish". DeseretNews.com. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- ^ Perego, Ugo A.; Myres, Natalie M.; Woodward, Scott R. (2005). "Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications". Journal of Mormon History. 31 (2): 42–60. JSTOR 23289931.

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 18–19). Two of the Smiths' children died in infancy. Hill (1977, pp. 32–35)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 18–19).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 18–19);Vogel (2004, pp. 16–17).

- ^ Hill, Donna (1977). Joseph Smith: The First Mormon (1st ed.). Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0-385-00804-X.

- ^ Vogel (2004, pp. 19–20).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 27–28).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 31);Vogel (2004, pp. 25–26). In 1818, the two Josephs and Hyrum Smith worked on a farm owned by one Jeremiah Hurlburt, but the relationship ended with each party suing the other.

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 76).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 32–34). Manchester was part of Farmington until 1821.

- ^ Berge (1985). The log house was built just outside their property in the town of Palmyra.

- ^ Vogel (2004, pp. 53, 68.)

- ^ Alvin Smith's death remains mysterious. Lucy thought it the result of a dose of Mercury(I) chloride, or calomel, given for "bilious fever" after he ate green turnips. Bushman (2005, p. 46). Alvin Smith may have died of appendicitis, hastened by the laxative. Joseph Smith Papers.

- ^ Joseph Smith Sr. confessed in 1834, "I have not always set that example before my family that I ought." Later, Joseph Smith Sr. told Hyrum he had "been out of the way through wine." Bushman (2005, p. 42) (noting that Smith's drinking was not excessive for the time and place). Vogel frankly calls Smith Sr.'s difficulty "low self-esteem and alcoholism."Vogel (2004, p. xx).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 47).

- ^ Smith may have attended school briefly in Palmyra. He later wrote that he was "deprived of the bennifit of an education" and that he had been instructed only in reading, writing, and the ground rules of arithmetic. Bushman (2005, pp. 41–42); Smith also may have been educated at home by his father, who had taught school some winters to make ends meet. Ostling & Ostling (1999, p. 23).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 34).

- ^ Vogel (2004, p. 27); Smith (1853, pp. 84–85).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 73); Bushman (2005, p. 35).

- ^ Tucker (1867, pp. 16–17); Vogel (2004, p. 27).

- ^ Turner (1852, p. 214); Quoted in Bushman (2005, pp. 37–38), and Brodie (1971, p. 26).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 18).

- ^ Randall Balmer, Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2004), 112; Michael McClymond, ed., Encyclopedia of Religious Revivals in America (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007), I, 63; Shipps (1985, p. 7). The heightened religious interest increased membership in traditional denominations, but many new sects and communitarian experiments also sprang from the movement in upstate New York including the American Shakers and the Oneida Community of John Humphrey Noyes. Ostling & Ostling (1999, pp. 20–21); Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800-1850 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1950).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 36–37, 46).

- ^ Backman (1969, p. 309)

- ^ Norton (1991, p. 255)

- ^ Quinn (2006)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 26).

- ^ Quoted in Bushman (2005, p. 25).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 25–26);Mack (1811, p. 25).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 23); Smith (1853, pp. 55–56).

- ^ Smith (1853, pp. 56, 58–59, 70–72, 74); Bushman (2005, p. 36)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 36)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 50); Quinn (1998, pp. 25–30): "Contemporary diaries, newspaper reports, and later town histories indicate that thousands of early Americans participated in treasure-digging nationwide. A smaller number actually took the lead in practicing various forms of divination and magic." (25)

- ^ Quinn (1998, p. 35).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 50)

- ^ Quoted in Bushman (2005, pp. 50).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 35–36);Brodie (1971, pp. 16) ("his reputation before he organized his church was not that of an adolescent mystic brooding over visions, but of a likable ne'er-do-well who was notorious for tall tales and necromantic arts and who spent his leisure leading a band of idler in digging for buried treasure."); Bushman (2005, p. 143) ("In the neighbors' reports, he was a plain rural visionary with little talent save a gift for seeing in a stone.")

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 36–37)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 36–38).

- ^ Matzko (2007, p. 70).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 37)

- ^ Quoted in Bushman (2008, p. 37)

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 26)

- ^ Orsamus Turner who reported Smith "catching a spark of Methodism on the Vienna road" visited Palmyra only between 1822 and 1828.Vogel (2004, p. 59).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 38); Vogel (2004, p. 61).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 90); Quoted in Brodie (1971, p. 26).

- ^ Vogel (2004, p. 61)"The fact that Joseph twice lifted the revival out of its historical context, pushing it back to 1823, then to 1820, indicates that he considered the revival of 1824-25 important to his genesis as a prophet. It seems evident that his quest for the true church began in 1824-25, not in 1820."

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 35, 38) (placing the First Vision around 1820)

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 39)

- ^ a b c Smith (1832, p. 3).

- ^ Joseph Smith Jr. dated the vision to when he was "a little over fourteen years of age" Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 1, p. 7), which would have been 1820. However, Smith's brother William stated it happened when Joseph was eighteen years old, when William himself would have been twelve Smith (1883, p. 6). For a discussion of these dating issues, see First Vision.

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 24); Bushman (2005, p. 39)

- ^ Smith (1884)(According to William, a minister had referred Smith to the scripture and suggested that he "ask of God");Bushman (2008, p. 38)

- ^ Smith (1883, p. 6).

- ^ Porter (1969, p. 330)

- ^ Anderson (1969, p. 7).

- ^ Pratt (1840, p. 5).

- ^ Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 1, p. 5); Brodie (1971, pp. 21–22)

- ^ "At first, Joseph was reluctant to talk about his vision. Most early converts probably never heard about the 1820 vision."Bushman (2005, p. 39)

- ^ Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 1, p. 5)

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 77).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 40) "Joseph did tell a Methodist preacher about the First Vision. Newly reborn people customarily talked over their experiences with a clergyman to test the validity of the conversion."

- ^ a b Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 1, p. 6)

- ^ Matzko (2007, p. 68). Dr. Matzko notes that "Oliver Cowdery claimed that Smith had been 'awakened' during a sermon by the Methodist minister George Lane."

- ^ Smith (1883, pp. 8–9).

- ^ Quinn (1998).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 40–41) "The preacher reacted quickly and negatively, not because of the strangeness of the story but because of its familiarity. Subjects of revivals all too often claimed to have seen visions."

- ^ Cobb (1881).

- ^ "When Joseph Smith first began to use his seer or "peep" stone he employed the folklore familiar to rural America. The details of his rituals and incantations are unimportant because they were commonplace, and Joseph gave up money-digging when he was twenty-one for a profession far more exciting." Brodie (1971, p. 21)

- ^ Harris (1859, p. 164); Mather (1880, p. 199). According to an account of an interview with Joseph Smith Sr., the 14-year-old Joseph borrowed a stone from a person working as a local crystal gazer Lapham (1870, pp. 305–306) which reportedly showed him the underground location of another stone near his home, which he located at a depth of about twenty-two feet. According to another story, in either 1819 Tucker (1867, p. 19) or 1822 Howe (1834, p. 240), while the older Smith males were digging a well for a Palmyra neighbor, they found an unusual stone Harris (1859, p. 163), described as either white and glassy and shaped like a child's foot or "chocolate-colored, somewhat egg-shaped." Roberts (1930, 1:129). Smith then used this stone as a seer stone.Tucker (1867, p. 20).

- ^ Ostling & Ostling (1999, p. 25).

- ^ Vogel (2004, p. 69).

- ^ Wade (1880).

- ^ Howe (1834, pp. 262–266)

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 262).

- ^ Vogel (2004, pp. 81).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 16).

- ^ Cowdery (1835, p. 200).

- ^ Vogel (1994, pp. 227, 229).

- ^ Smith (1976, p. 120); Quoted in Brodie (1971, pp. 20–21)

- ^ Roberts (1902, p. 17).

- ^ The date of Moroni's first visits is generally taken as 1823. However, Smith's 1832 history (his first written account) dates the visit of Moroni to September 22, 1822, a year earlier, although he also states he was seventeen years old (Smith 1832, p. 3), and his seventeenth birthday would not have been until December 23, 1822. Further possible ambiguity arises because in an 1830 interview, Joseph Smith Sr. reportedly claimed that he was not told about Moroni's visit until a year after the fact, during which Smith Jr. had been collecting items in preparation for receiving the plates (Lapham 1870, p. 305). Lucy Mack Smith asserts that Smith Sr. was told about Moroni's visit in 1823, the day after Moroni's first visit (Smith (1853, p. 82)); however, Lucy's history also indicates that after the appearance of the angel, Joseph had made two annual visits to the hill Cumorah before the 1823 death of her son Alvin (Smith 1853, p. 85), which Lucy incorrectly dated to 1824 (Smith 1853, p. 87).

- ^ As originally taken down in dictation and published, the story stated that the angel was Nephi.[citation needed] Long after Smith's death, however, this reference to Nephi in the official history was changed to Moroni (Roberts 1902) to conform to Smith's other statements from as early as 1835 that refer to the latter.[citation needed] Generally, modern historians refer to this angel as Moroni.

- ^ Skousen, R. (2010). The Book of Mormon: the earliest text. New Haven: Yale University Press. page xi

- ^ Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 2, p. 14)

- ^ Smith (1853, pp. 83–84); Smith (1883, pp. 9–10).

- ^ Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 2, p. 15)

- ^ Roberts (1902, vol. 1, ch. 2, p. 13)

- ^ a b c d e f Knight (1833, p. 2).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 252).

- ^ Lapham (1870, p. 305).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 242).

- ^ Smith (1853, pp. 85–86).

- ^ Lapham (1870, pp. 305–306).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 85).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 86); Lapham (1870, p. 305).

- ^ a b Harris (1859, p. 164).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 243).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 243). In addition to the Urim and Thummim, Smith also reportedly discovered at some point that the box, or the ground nearby, contained several other artifacts, including the Liahona, the sword of Laban (Lapham 1870, p. 306), the vessel in which the gold was melted, a rolling machine for gold plates, and three balls of gold as large as a fist (Howe 1834, p. 253).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 99).

- ^ a b c Knight (1833, p. 3).

- ^ Knight (1833, p. 3); Smith (1853, p. 99).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 100).

- ^ Harris (1859, p. 164).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 246); Harris (1859, p. 165).

- ^ a b Smith (1853, p. 101).

- ^ a b Harris (1859, p. 167).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 102).

- ^ Smith (1853, pp. 103–104).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 246); Smith (1853, pp. 104–06); Harris (1859, p. 166).

- ^ Smith (1842).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 264); Harris (1859, pp. 169–70); Smith (1884).

- ^ a b Smith (1853).

- ^ Smith (1853, pp. 107–09).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 110).

- ^ Howe (1834, p. 260).

- ^ Howe (1834, pp. 255).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 109).

- ^ Harris (1859, pp. 167–68).

- ^ Harris (1859, pp. 168–69).

- ^ Harris (1859, p. 169).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 113).

- ^ a b Harris (1859, p. 170).

References

- Abanes, Richard (2003), One Nation Under Gods: A History of the Mormon Church, Thunder's Mouth Press, ISBN 1-56858-283-8

- Anderson, Richard Lloyd (1969), "Circumstantial Confirmation Of the first Vision Through Reminiscences" (PDF), BYU Studies, 9 (3): 373–404[permanent dead link].

- Backman, Milton V. Jr. (1969), "Awakenings in the Burned-over District: New Light on the Historical Setting of the first Vision" (PDF), BYU Studies, 9 (3): 301–315[permanent dead link].

- Benton, Josiah Henry (1911), Warning Out in New England, Boston: W.B. Clarke.

- Berge, Dale L. (August 1985), "Archaeological Work at the Smith Log House", Ensign, 15 (8): 24.

- Bidamon, Emma Smith (March 27, 1876), "Letter to Emma S. Pilgrim", in Vogel, Dan (ed.), Early Mormon Documents, vol. 1, Signature Books (published 1996), ISBN 1-56085-072-8.

- Booth, Ezra (October 20, 1831a), "Mormonism—No. II (Letter to the editor)", The Ohio Star, 2 (42): 1.

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1971), No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (2nd ed.), New York: Knopf, ISBN 0-394-46967-4.

- Brooke, John L. (1994), The Refiner's Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005), Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, New York: Knopf, ISBN 1-4000-4270-4.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2008). Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Vol. 183. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531030-6.

- Cobb, James T. (June 1, 1881), "The Hill Cumorah, And The Book Of Mormon. The Smith Family, Cowdery, Harris, and Other Old Neighbors—What They Know", The Saints' Herald, 28 (11): 167.

- Cowdery, Oliver (1834), "Letter [I]", Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate, 1 (1): 13–16.

- Cowdery, Oliver (1834), "Letter III", Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate, 1 (3): 41–43.

- Cowdery, Oliver (1835), "Letter VIII", Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate, 2 (1): 195–202.

- Harris, Martin (1859), "Mormonism—No. II", Tiffany's Monthly, 5 (4): 163–170.

- Hill, Donna (1999), Joseph Smith: The First Mormon, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-118-X, archived from the original on July 23, 2011.

- Hill, Marvin S. (1976), "Joseph Smith and the 1826 Trial: New Evidence and New Difficulties" (PDF), BYU Studies, 12 (2): 1–8[permanent dead link].

- Hitchens, Christopher (2007), god is not Great, New York: Twelve, pp. 161–168.

- Howe, Eber Dudley (1834), Mormonism Unvailed, Painesville, Ohio: Telegraph Press.

- Knight, Joseph Sr. (1833), Jessee, Dean (ed.), "Joseph Knight's Recollection of Early Mormon History" (PDF), BYU Studies, 17 (1) (published 1976): 35[permanent dead link].

- Lapham, [La]Fayette (1870), "Interview with the Father of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet, Forty Years Ago. His Account of the Finding of the Sacred Plates", Historical Magazine, Second series, 7: 305–309

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link). - Lewis, Joseph; Lewis, Hiel (April 30, 1879), "Mormon History", Amboy Journal, vol. 24, no. 5, p. 1.

- Mack, Solomon (1811), A Narraitve [sic] of the Life of Solomon Mack, Windsor: Solomon Mack.

- Mather, Frederic G. (1880), "Early Days of Mormonism", Lippincott's Magazine, 26 (152): 198–211.

- Matzko, John (2007), "The Encounter of the Young Joseph Smith with Presbyterianism", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 68–84.

- Norton, Walter A. (1991), Comparative Images: Mormonism and Contemporary Religions as Seen by Village Newspapermen in Western New York and Northeastern Ohio, 1820–1833, Ph.D. dissertation, BYU.

- Norwich, Vermont (March 15, 1816), "Excerpt: A Record of Strangers Who are Warned Out of Town, 1813–1818, Norwich Clerk's Office, p. 53", in Dan, Vogel (ed.), Early Mormon Documents, vol. 1, Signature Books (published 1996), p. 666, ISBN 1-56085-072-8.

- Ostling, Richard; Ostling, Joan K. (1999), Mormon America: The Power and the Promise, San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, ISBN 0-06-066371-5.

- Palmer, Grant H. (2002), An Insider's View of Mormon Origins, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-157-0.

- Phelps, W.W., ed. (1833), A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ, Zion: William Wines Phelps & Co..

- Porter, Larry C. (1969), "Reverend George Lane—Good "Gifts", Much "Grace", and Marked "Usefulness"" (PDF), BYU Studies, 9 (3): 321–40[permanent dead link].

- Porter, Larry C. (1971), A Study of the Origins of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the States of New York and Pennsylvania, 1816–1831, Ph.D. dissertation, BYU.

- Pratt, Orson (1840), A Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, and of the Late Discovery of Ancient American Records, Edinburgh: Ballantyne and Hughes.

- Quinn, D. Michael (1998), Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (2d ed.), Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-089-2.

- Quinn, D. Michael (2006), "Joseph Smith's Experience of a Methodist 'Camp-Meeting' in 1820", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. Dialogue Paperless., no. 3.

- Roberts, B. H., ed. (1902), History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, vol. 1, Salt Lake City: Deseret News.

- Roberts, B. H., ed. (1930), A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Century I, Brigham Young University Press, ISBN 0-8425-0482-6.

- Shipps, Jan (1985). Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01417-0.

- Smith, Joseph III (October 1, 1879), "last Testimony of Sister Emma", The Saints' Herald, 26 (19): 289.

- Smith, Joseph (March 26, 1830b), The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon, Upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi, Palmyra, New York: E. B. Grandin.

- Smith, Joseph (1832), "History of the Life of Joseph Smith", in Jessee, Dean C (ed.), Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book (published 2002), ISBN 1-57345-787-6, archived from the original on 2008-11-20.

- Smith, Joseph; Cowdery, Oliver; Rigdon, Sidney; Williams, Frederick G. (1835), Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints: Carefully Selected from the Revelations of God, Kirtland, Ohio: F. G. Williams & Co.

- Smith, Joseph; et al. (1838–1842), "History of the Church, Ms. A–1 (LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City)", in Jessee, Dean C (ed.), Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book (published 2002), ISBN 1-57345-787-6.

- Smith, Joseph (March 1, 1842), "Church History [Wentworth Letter]", Times and Seasons, 3 (9): 706–10.

- Smith, Joseph Fielding (1976), Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ISBN 0-87747-626-8.

- Smith, Lucy Mack (1853), Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations, Liverpool: S.W. Richards, ISBN 978-1-4254-8383-8.

- Smith, Lucy Mack (1901), History of Joseph Smith, Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft.

- Smith, William (1883), William Smith on Mormonism: A True Account of the Origin of the Book of Mormon, Lamoni, Iowa: RLDS Church.

- Smith, William (1884), "The Old Soldier's Testimony", The Saints' Herald, 34 (39): 643–44.

- Stevenson, Edward (1882), "One of the Three Witnesses: Incidents in the Life of Martin Harris", The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star, 44: 78–79, 86–87.

- Tucker, Pomeroy (1867), Origin, Rise and Progress of Mormonism, New York: D. Appleton.

- Turner, Orsamus (1852), History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps and Gorham's Purchase, and Morris' Reserve, Rochester, New York: William Alling, ISBN 9781404752023.

- Vogel, Dan (1994), "The Locations of Joseph Smith's Early Treasure Quests" (PDF), Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 27 (3): 197–231, doi:10.2307/45225965, JSTOR 45225965, S2CID 254306928.

- Vogel, Dan (2004), Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet, Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-179-1.

- Wade, B. (April 23, 1880), "An Interesting Document", The Salt Lake Daily Tribune, vol. 19, no. 8.

- Whitmer, David (1887), An Address to All Believers in Christ By A Witness to the Divine Authenticity of the Book of Mormon, Richmond, Missouri: David Whitmer.