WASP-103

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Hercules |

| Right ascension | 16h 37m 15.5766s[1] |

| Declination | 07° 11′ 00.110″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 12.1[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | main-sequence star[3] |

| Spectral type | F8V[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −40.69±1.00[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −9.756[1] mas/yr Dec.: 2.779[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 1.8332 ± 0.1073 mas[1] |

| Distance | 1,800 ± 100 ly (550 ± 30 pc) |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.220+0.039 −0.036[4] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.436+0.052 −0.031[4] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 3.3[1] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.35±0.02[1] cgs |

| Temperature | 6110±160[5] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.06±0.13[4] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 10.60±0.90[4] km/s |

| Age | 4±1[4] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

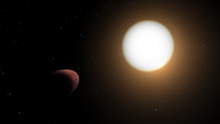

WASP-103 is an F-type main-sequence star located 1,800 ± 100 light-years (550 ± 30 parsecs) away in the constellation Hercules. Its surface temperature is 6,110±160 kelvins (K). The star's concentration of heavy elements is similar to that of the Sun.[4] WASP-103 is slightly younger than the Sun at 4±1 billion years.[4] The chromospheric activity of the star is elevated due to interaction with the giant planet on a close-in orbit.[5]

A multiplicity survey in 2015 found a suspected stellar companion to WASP-103, at a projected separation of 0.242″±0.016″.[7]

Planetary system

In 2014 one super-Jupiter planet, named WASP-103b, was discovered by the transit method.[8] The planet is orbiting its host star in 22 hours and may be close to the limit of tidal disruption.[2] Orbital decay was not detected by 2020.[9] In early 2022, the planet was popularized because of its shape similar to a potato.[10]

The planetary atmosphere contains water, and possibly hydrogen cyanide, titanium(II) oxide, or sodium.[11] The planet has an elevated carbon to oxygen molar fraction of 0.9[3] or 1.35+0.14

−0.17, therefore it is nearly certain to be a carbon planet.[12]

The planetary equilibrium temperature is 2,484±67 K, although a big difference exists between the night side and day side. The dayside temperature is 2,930±40 K, while the night side temperature is 1,880±40 K.[3]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 1.455+0.090 −0.091 MJ |

0.01987+0.00020 −0.00021 |

0.9255456±0.0000013 | <0.15 | 87.3±1.2° | 1.528+0.073 −0.047 RJ |

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c Gillon, M.; Anderson, D. R.; Collier-Cameron, A.; Delrez, L.; Hellier, C.; Jehin, E.; Lendl, M.; Maxted, P. F. L.; Pepe, F.; Pollacco, D.; Queloz, D.; Ségransan, D.; Smith, A. M. S.; Smalley, B.; Southworth, J.; Triaud, A. H. M. J.; Udry, S.; Van Grootel, V.; West, R. G. (2014). "WASP-103 b: A new planet at the edge of tidal disruption". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 562: L3. arXiv:1401.2784. Bibcode:2014A&A...562L...3G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201323014. S2CID 53680974.

- ^ a b c Kreidberg, Laura; Line, Michael R.; Parmentier, Vivien; Stevenson, Kevin B.; Louden, Tom; Bonnefoy, Mickäel; Faherty, Jacqueline K.; Henry, Gregory W.; Williamson, Michael H.; Stassun, Keivan; Beatty, Thomas G.; Bean, Jacob L.; Fortney, Jonathan J.; Showman, Adam P.; Désert, Jean-Michel; Arcangeli, Jacob (2018). "Global Climate and Atmospheric Composition of the Ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-103b fromHSTandSpitzer Phase Curve Observations". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (1): 17. arXiv:1805.00029. Bibcode:2018AJ....156...17K. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aac3df. S2CID 56157823.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Bonomo, A. S.; et al. (2017). "The GAPS Programme with HARPS-N at TNG". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 602: A107. arXiv:1704.00373. Bibcode:2017A&A...602A.107B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629882. S2CID 118923163.

- ^ a b Staab, D.; Haswell, C. A.; Smith, Gareth D.; Fossati, L.; Barnes, J. R.; Busuttil, R.; Jenkins, J. S. (2017). "SALT observations of the chromospheric activity of transiting planet hosts: Mass-loss and star–planet interactions". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 466 (1): 738–748. arXiv:1612.01739. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.466..738S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw3172.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "WASP-103". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

- ^ Wöllert, Maria; Brandner, Wolfgang (2015). "A Lucky Imaging search for stellar sources near 74 transit hosts". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 579: A129. arXiv:1506.05456. Bibcode:2015A&A...579A.129W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201526525. S2CID 118903879.

- ^ Southworth, John; Mancini, L.; Ciceri, S.; Budaj, J.; Dominik, M.; Figuera Jaimes, R.; Haugbølle, T.; Jørgensen, U. G.; Popovas, A.; Rabus, M.; Rahvar, S.; von Essen, C.; Schmidt, R. W.; Wertz, O.; Alsubai, K. A.; Bozza, V.; Bramich, D. M.; Calchi Novati, S.; d'Ago, G.; Hinse, T. C.; Henning, Th.; Hundertmark, M.; Juncher, D.; Korhonen, H.; Skottfelt, J.; Snodgrass, C.; Starkey, D.; Surdej, J. (2015). "High-precision photometry by telescope defocusing – VII. The ultrashort period planet WASP-103★". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 447 (1): 711–721. arXiv:1411.2767. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.447..711S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Patra, Kishore C.; Winn, Joshua N.; Holman, Matthew J.; Gillon, Michael; Burdanov, Artem; Jehin, Emmanuel; Delrez, Laetitia; Pozuelos, Francisco J.; Barkaoui, Khalid; Benkhaldoun, Zouhair; Narita, Norio; Fukui, Akihiko; Kusakabe, Nobuhiko; Kawauchi, Kiyoe; Terada, Yuka; Bouma, L. G.; Weinberg, Nevin N.; Broome, Madelyn (2020). "The Continuing Search for Evidence of Tidal Orbital Decay of Hot Jupiters". The Astronomical Journal. 159 (4): 150. arXiv:2002.02606. Bibcode:2020AJ....159..150P. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab7374. S2CID 211066260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Astronomers Discover Planet That Looks Like a Rugby Ball". NDTV Gadgets 360. 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ Wilson, Jamie; Gibson, Neale P.; Nikolov, Nikolay; Constantinou, Savvas; Madhusudhan, Nikku; Goyal, Jayesh; Barstow, Joanna K.; Carter, Aarynn L.; De Mooij, Ernst J W.; Drummond, Benjamin; Mikal-Evans, Thomas; Helling, Christiane; Mayne, Nathan J.; Sing, David K. (2020). "Ground-based transmission spectroscopy with FORS2: A featureless optical transmission spectrum and detection of H2O for the ultra-hot Jupiter WASP-103b". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 497 (4): 5155–5170. arXiv:2007.13510. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.497.5155W. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa2307.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ THERMAL EMISSION FROM THE HOT JUPITER WASP-103 b IN 𝐽 AND 𝐾s BANDS, 2023, arXiv:2303.13732