Coastal defence and fortification

Coastal defence (or defense) and coastal fortification are measures taken to provide protection against military attack at or near a coastline (or other shoreline),[1] for example, fortifications and coastal artillery. Because an invading enemy normally requires a port or harbour to sustain operations, such defences are usually concentrated around such facilities, or places where such facilities could be constructed.[2] Coastal artillery fortifications generally followed the development of land fortifications, usually incorporating land defences; sometimes separate land defence forts were built to protect coastal forts. Through the middle 19th century, coastal forts could be bastion forts, star forts, polygonal forts, or sea forts, the first three types often with detached gun batteries called "water batteries".[3] Coastal defence weapons throughout history were heavy naval guns or weapons based on them, often supplemented by lighter weapons. In the late 19th century separate batteries of coastal artillery replaced forts in some countries; in some areas these became widely separated geographically through the mid-20th century as weapon ranges increased. The amount of landward defence provided began to vary by country from the late 19th century; by 1900 new US forts almost totally neglected these defences. Booms were also usually part of a protected harbor's defences. In the middle 19th century underwater minefields and later controlled mines were often used, or stored in peacetime to be available in wartime. With the rise of the submarine threat at the beginning of the 20th century, anti-submarine nets were used extensively, usually added to boom defences, with major warships often being equipped with them (to allow rapid deployment once the ship was anchored or moored) through early World War I. In World War I railway artillery emerged and soon became part of coastal artillery in some countries; with railway artillery in coast defence some type of revolving mount had to be provided to allow tracking of fast-moving targets.[4]

In littoral warfare, coastal defence counteracts naval offence, such as naval artillery, naval infantry (marines), or both.

History

Rather than the beach assault of modern amphibious operations, seaborne assaults of the classical and medieval age more often took the form of raiders sailing up river and landing well inland of the coast. Prior to the invention of naval artillery that could sink hostile ships, the most that coastal defence could do was act as an early warning system, that could alert local naval or ground forces of the impending attack. For example, in the late Roman period the Saxon Shore was a system of forts at the mouths of navigable rivers, and watch towers along the coast of Britannia and Gaul.

Later in Anglo-Saxon Wessex protection against Viking raiders took the form of coast watchers whose duty was to alert the local militia; the navy, which would attempt to intercept the raider's ships or failing that to destroy them after they had beached, against smaller raiding forces the threat of losing their ships, and their way home with their loot was often enough to force them to curtail their attack. In addition there was a system of fortified towns, burghs, that were positioned at choke points along navigable rivers to prevent raiders from sailing inland.

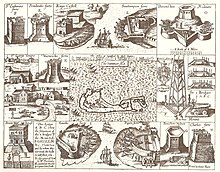

Sea forts

Sea forts are completely surrounded by water – if not permanently, then at least at high tide (i.e. they are tidal islands).

Unlike most coastal fortifications, which are on the coast, sea forts are not. Instead, they are off the coast on islands, artificial islands, or are specially built structures. Some sea forts, such as Fort Denison or Fort Sumter, are within harbours in proximity to the coast, but most are at some distance off the coast. Some, such as for example Bréhon Tower or Fort Drum completely occupy small islands; others, such as Flakfortet and Pampus, are on artificial islands built up on shoals. Fort Louvois is on a built-up island, 400 meters (1,312 ft) from the shore, and connected to it by a causeway that high tide completely submerses. The most elaborate sea fort is Murud-Janjira, which is so extensive that one might truly call it a sea fortress.[according to whom?]

The most recent sea forts were the Maunsell Forts, which the British built during World War II as anti-aircraft platforms. One type consisted of a concrete pontoon barge on which stood two cylindrical towers on top of which was the gun platform mounting. They were laid down in dry dock and assembled as complete units. They were then fitted out before being towed out and sunk onto their sand bank positions in 1942. The other type consisted of seven interconnected steel platforms built on stilts. Five platforms carried guns arranged in a semicircle around the sixth platform, which contained the control centre and accommodation. The seventh platform, set further out than the gun towers, was the searchlight tower.

Coastal defence and fortification by country

Chile

In Colonial times the Spanish Empire diverted significant resources to fortify the Chilean coast as consequence of Dutch and English raids.[5]

The Dutch occupation of Valdivia in 1643 caused great alarm among Spanish authorities and triggered the construction of the Valdivian Fort System that begun in 1645.[6][7]

As consequence of the Seven Years' War the Valdivian Fort System was updated and reinforced from 1764 onwards. Other vulnerable localities of colonial Chile such as Chiloé Archipelago, Concepción, Juan Fernández Islands and Valparaíso were also made ready for an eventual English attack.[8][5] Inspired in the recommendations of former governor Santa María the Spanish founded the "city-fort" of Ancud in 1768 and separated Chiloé from the Captaincy General of Chile into a direct dependency of the Viceroyalty of Peru.[9]

China

China first established formal coastal defences during the early Ming dynasty (14th century) to protect against attacks by pirates (wokou). Coastal defences were maintained through both the Ming dynasty and the Qing dynasty that followed, protecting the coast against pirates, and against the Portuguese and other European powers that sought to impose their will on China.[10][11]

Subsequently, the European powers built their own coastal defences to protect the various colonial enclaves that they established along the Chinese coast. One such, a fort built by the British commanding the Lei Yue Mun channel between Hong Kong Island and the mainland, has been converted into the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence. This tells the story of coastal defence along the South China coast from the Ming dynasty onwards.[12]

Taiwan has several coastal fortifications, with some, such as Fort Zeelandia or Anping Castle dating to the time of the Dutch East India Company. Others, such as Cihou Fort, Eternal Golden Castle, Hobe Fort, date more to the end of the 19th century. The Uhrshawan Battery dates primarily to the first half of the 19th century. It actually underwent bombardment during the Sino-French War.

Malta

The islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino all have some form of coastal fortification. The area around the Grand Harbour was possibly first fortified during Arab rule, and by the 13th century, a castle known as the Castrum Maris was built in Birgu to protect the harbour. The Maltese islands were given to Order of Saint John in 1530, who settled in Birgu and rebuilt the Castrum Maris as Fort Saint Angelo. In the 1550s, Fort Saint Elmo and Fort Saint Michael were built, and walls surrounded the coastal cities of Birgu and Senglea. In 1565, the Great Siege of Malta reduced many of these coastal fortifications to rubble, but after the siege they were rebuilt. The fortified city of Valletta was built on the Sciberras Peninsula, and further modifications were made to the fortifications over the years. The harbour area was strengthened even more by the building of the Floriana Lines, Santa Margherita Lines, Cottonera Lines and Fort Ricasoli in the 17th century and Fort Manoel and Fort Tigné in the nearby Marsamxett Harbour in the 18th century. The Order also built Fort Chambray near Mġarr Harbour in Gozo.

In the early 15th century, a number of watch posts had been established around Malta's coastline. In the early 17th century, the Order began to strengthen the coastal fortifications outside the harbour area, by building watchtowers. The first of these was Garzes Tower, which was built in 1605. The Wignacourt, Lascaris and De Redin towers were built over the course of the 17th century. The last coastal watchtower to be built was Isopu Tower in 1667. Between 1605 and 1667, a total of 31 towers were built, of which 22 survive today (with another 3 in ruins).[13]

From 1714 onwards, about 52 batteries and redoubts, along with several entrenchments, were built around the coasts of Malta and Gozo. Many of these have been destroyed, but a few examples still survive.[14]

After the British took Malta in 1800, they modified the Order's defences in the harbour area to keep up with new technology. Malta itself, Gibraltar, Bermuda, and Halifax, Nova Scotia were designated Imperial fortresses. The Corradino Lines were built in the 1870s to protect the Grand Harbour from landward attacks. Between 1872 and 1912, many forts and batteries were built around the coastline. The first of these was Sliema Point Battery, built to protect the northern approach to the Grand Harbour. A chain of fortifications, including Fort Delimara and Fort Benghisa, was also built to protect Marsaxlokk Harbour.

From 1935 to the 1940s, the British built many pillboxes in Malta for defence in case of an Italian invasion.

New Zealand

The coastline of New Zealand was fortified in two main waves. The first wave occurred around 1885 and was a response to fears of an attack by Russia. The second wave occurred during World War II and was due to fears of invasion by the Japanese.[15]

The fortifications were built from British designs adapted to New Zealand conditions. These installations typically included gun emplacements, pill boxes, fire command or observation posts, camouflage strategies, underground bunkers, sometimes with interconnected tunnels, containing magazines, supply and plotting rooms and protected engine rooms supplying power to the gun turrets and searchlights.[15]

United States

The defence of its coasts was a major concern for the United States from its independence. Prior to the American Revolution many coastal fortifications already dotted the Atlantic coast, as protection from pirate raids and foreign incursions. The Revolutionary War led to the construction of many additional fortifications, mostly comprising simple earthworks erected to meet specific threats.[16]

The prospect of war with European powers in the 1790s led to a national programme of fortification building spanning seventy years in three phases, known as the First, Second and Third Systems. By the time of the American Civil War, advances in armour and weapons had made masonry forts obsolete, and the combatants discovered that their steamships and ironclad warships could penetrate Third System defences with acceptable losses.[16][17]

In 1885 US President Grover Cleveland appointed the Endicott Board, whose recommendations would lead to a large-scale modernization programme of harbour and coastal defences in the United States, especially the construction of well dispersed, open topped reinforced concrete emplacements protected by sloped earthworks. Many of these featured disappearing guns, which sat protected behind the walls, but could be raised to fire. Underwater mine fields were a critical component of the defence, and smaller guns were also employed to protect the mine fields from minesweeping vessels. Defences of a given harbor were initially designated artillery districts, redesignated as coast defense commands in 1913 and as harbor defense commands in 1924. In 1901 the Artillery Corps was divided into field artillery and coast artillery units, and in 1907 the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps was created to operate these defences.[16]

The development of military aviation rendered these open topped emplacements vulnerable to air attack. Therefore, the next, and last, generation of coastal artillery was mounted under thick concrete shields covered with vegetation to make them virtually invisible from above. In anticipation of a conflict with Japan, most of the limited funds available between 1933 and 1938 were spent on the Pacific coast. In 1939–40 the threat of war in Europe prompted larger appropriations and the resumption of work along the Atlantic coast. Under a major program developed in the wake of the Fall of France in 1940, a near-total replacement of previous coast defenses was implemented, centered on 16-inch guns in new casemated batteries. These were supplemented by 6-inch and 90 mm guns, also in new installations.[16]

In WW2 the U.S. Coast Guard would patrol the shores of the United States during the war. Some patrolled on horseback with mounted beach patrols. On 13 June 1942 Seaman 2nd Class John Cullen, patrolling the beach in Amagansett, New York, discovered the first landing of German saboteurs in Operation Pastorius. Cullen was the first American who actually came in contact with the enemy on the shores of the United States during the war and his report led to the capture of the German sabotage team. For this, Cullen received the Legion of Merit.[18]

United Kingdom

The walls around coastal cities, such as Southampton, had evolved from simpler Norman fortifications by the start of the 13th century. Later, King Edward I was a prolific castle builder and sites such as Conwy Castle, built 1283 to 1289, defend river approaches as well as the surrounding land. Built 1539 to 1544, the Device Forts are a series of artillery fortifications built for Henry VIII to defend the southern coast of England. Between 1804 and 1812 the British authorities built a chain of towers known as Martello Towers to defend the south and east coast of England, Ireland, Jersey and Guernsey against possible invasion from France. This type of tower was also used elsewhere in the British Empire and in the United States.

In the early Victorian era, Alderney was strongly fortified to provide a massive anchorage for the British Navy before France became an ally of Britain in the Crimean War, even so plans changed slowly and the Palmerston Forts, a group of forts and associated structures were built during the Victorian period on the recommendations of the 1860 Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom, following concerns about the strength of the French Navy.[19] In 1865 Lieutenant Arthur Campbell Walker, of the School of Musketry advocated the use of armoured trains on "an iron high-road running parallel with that other 'silent highway', the source of all our greatness, the ocean, our time-honoured 'moat and circumvallation'"[20]

During the First World War the British Admiralty designed eight towers code named M-N that were to be built and positioned in the Straits of Dover to protect allied merchant shipping from German U-boats. Nab Tower is still in situ. The Maunsell Forts were small fortified towers, primarily for anti-aircraft guns, built in the Thames and Mersey estuaries during the Second World War.

With the advent of missile technology coastal forts became obsolete. Britain's coastal forts were therefore decommissioned in 1956 and the units manning them disbanded.[21]

Russian Federation

Russia Federation developed A-222E Bereg-E 130mm coastal mobile artillery system, K-300P Bastion-P coastal defence system and Bal-E coastal missile complex with Kh-35/Kh-35E missiles.

See also

References

- ^ Brown, William Baker (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 599–602.

- ^ "Coastal Defense". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ Weaver II, John R. (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867, 2nd Ed. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. pp. 16–17, 24–34. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.

- ^ Hogg, Ian V. (2002). British & American Artillery of World War II. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. pp. 180–181. ISBN 1-85367-478-8.

- ^ a b "Ingeniería Militar durante la Colonia". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Robbert Kock The Dutch in Chili Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine at coloniavoyage.com

- ^ Kris E. Lane Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas, 1500–1750, 1998, pages 88–92

- ^ "Lugares estratégicos", Memoria chilena (in Spanish), Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, retrieved 30 December 2015

- ^ Urbina Carrasco, María Ximena (2014). "El frustrado fuerte de Tenquehuen en el archipiélago de los Chonos, 1750: Dimensión chilota de un conflicto hispano-británico". Historia. 47 (I). Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Gallery 2: The Ming Period (1368–1644)". Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence. Archived from the original on 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ^ "Gallery 3: The Qing Period (1644–1911)". Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence. Archived from the original on 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ^ "History". Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence. Archived from the original on 2009-05-26. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ^ Debono, Charles. "Coastal Towers". Mellieha.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Spiteri, Stephen C. (10 April 2010). "18th Century Hospitaller Coastal Batteries". MilitaryArchitecture.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ a b Baigent, Captain AJ (1959). "Coast Artillery Defences". Royal New Zealand Artillery Association. Archived from the original on 2009-10-17. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ^ a b c d Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Third Edition. CDSG Press. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Coastal Defense". United States National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-07-23. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Brown, D. (2006). "Palmerston and Anglo—French Relations, 1846—1865". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 17 (4): 675–692. doi:10.1080/09592290600942918. S2CID 154025726.

- ^ Walker, Arthur (2000) [1865], "Coast Railways and Railway Artillery", Journal of the Royal United Services Institute, Pallas Armata, pp. 221–234

- ^ Maurice-Jones, Col. K.W (2005) [1957]. The History of Coast Artillery in the British Army (Reprint). N&M Press. ISBN 9781845740313.