Apusomonadidae

| Apusomonadidae | |

|---|---|

| |

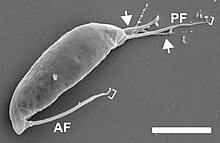

| Podomonas kaiyoae SEM image | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Amorphea |

| Clade: | Obazoa |

| Class: | Thecomonadea Cavalier-Smith, 1993 emend. 2013[2] |

| Order: | Apusomonadida Karpov & Mylnikov, 1989[1] |

| Family: | Apusomonadidae Karpov & Mylnikov, 1989[1] |

| Genera | |

| Diversity | |

| 28 species | |

The apusomonads (order Apusomonadida) are a group of protozoan zooflagellates that glide on surfaces, and mostly consume prokaryotes. They are of particular evolutionary interest because they appear to be the sister group to the Opisthokonts, the clade that includes both animals and fungi. Together with the Breviatea, these form the Obazoa clade.[3][4][5]

Characteristics

Apusomonads are small gliding heterotrophic biflagellates (i.e. with two flagella) that possess a proboscis, formed partly or entirely by the anterior flagellum surrounded by a membranous sleeve. There is a pellicle under the dorsal cell membrane that extends into the proboscis sleeve and into a skirt that covers the sides of the cell. Apusomonads present two different cell plans:[6]

- Derived cell plan, represented by Apusomonas, with a round cell body and a mastigophore, a projection of the cell containing both basal bodies at its end.[6]

- "Amastigomonas-like" cell plan, with an oval or oblong cell that generally forms pseudopodia from the ventral surface, with no mastigophore, and the proboscis comprising solely the flagellum and the sleeve. These characteristics are considered 'primitive' or 'ancestral' in comparison with Apusomonas. Organisms with this body plan, although historically assigned to the same genus Amastigomonas, are a paraphyletic group from which Apusomonas has evolved.[6][7]

Evolution

External relationships

The apusomonads are the sister group to Opisthokonta, the lineage that includes animals, fungi and an array of related protists. Because of this, apusomonads occupy an important phylogenetic position to understand eukaryotic evolution. They retain ancestral characteristics, such as the biflagellate body plan, which in opisthokonts evolves into a uniflagellate plan.[7]

Apusomonads are vital to understanding multicellularity. Genes involved in multicellularity have been found in the apusomonad Thecamonas,[8] such as adhesion proteins, calcium-signaling genes and types of sodium channels characteristic of animals.[6] The genome of the strain "Amastigomonas sp." presents the integrin-mediated adhesion machinery, the primary cell-matrix adhesion mechanism seen in Metazoa (animals).[9]

Internal relationships

Apusomonads are a poorly and narrowly studied group.[6] Currently, the diversity of described apusomonads consists of the round Apusomonas and a wide array of "Amastigomonas-type" organisms that have been reclassified into the genera Thecamonas, Manchomonas, Podomonas, Multimonas, Chelonemonas and, most recently, Catacumbia, Cavaliersmithia, Karpovia, Mylnikovia and Singekia. The relationships between these genera are depicted by the cladogram below.[7]

| Apusomonadida | "Amastigomonas-like" organisms | |

Taxonomy

History

Apusomonads were first described in 1989 as one family Apusomonadidae inside the monotypic order Apusomonadida, as a group of flagellates containing the genera Apusomonas and Amastigomonas.[1] Later, British protozoologist Thomas Cavalier-Smith classified them within the monotypic class Thecomonadea as part of the paraphyletic phylum Apusozoa.[2] Modern cladistic approaches to eukaryotic classification refer to apusomonads by their order-level name alone.[7][10]

Classification

There are 10 recognized genera, as well as the "Amastigomonas-like" archetype that includes primitive forms not yet transferred to new genera.[7]

- "Amastigomonas" de Saedeleer 1931

- A. caudata Mylnikov 1989 [Amastigomonas borokensis Hamar 1979]

- A. debruynei de Saedeleer 1931

- A. marisrubri Mylnikov & Mylnikov 2012

- Apusomonas Alexeieff 1924 [Rostromonas Karpoff & Zhukov 1980]

- A. australiensis Ekelund & Patterson 1997

- A. proboscidea Alexeieff 1924 [Rostromonas applanata Karpoff & Zhukov 1980]

- Catacumbia Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022[7]

- C. lutetiensis Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- Cavaliersmithia Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- C. chaoae Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- Karpovia Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- K. croatica Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- Manchomonas Cavalier-Smith 2010

- Manchomonas bermudensis (Molina & Nerad 1991) Cavalier-Smith 2010 [Amastigomonas bermudensis Molina & Nerad 1991]

- Multimonas Cavalier-Smith 2010

- M. koreensis Heiss, Lee, Ishida & Simpson, 2015

- M. marina (Mylnikov 1989) Cavalier-Smith 2010 [Cercomonas marina Mylnikov 1989; Amastigomonas marina (Mylnikov 1989) Mylnikov 1999]

- M. media Cavalier-Smith 2010

- Mylnikovia Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- M. oxoniensis (Cavalier-Smith 2010) Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022 [Thecamonas oxoniensis Cavalier-Smith 2010]

- Podomonas Cavalier-Smith 2010

- P. capensis Cavalier-Smith 2010

- P. gigantea (Mylnikov 1999) [Amastigomonas gigantea Mylnikov 1999]

- P. griebenis (Mylnikov 1999) [Amastigomonas griebenis Mylnikov 1999]

- P. kaiyoae Yabuki in Yabuki, Tame & Mizuno 2022[11]

- P. klosteris (Arndt & Mylnikov 1999) Cavalier-Smith 2010 [Amastigomonas klosteris Arndt & Mylnikov 1999]

- P. magna Cavalier-Smith 2010

- Singekia Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- S. franciliensis Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- S. montserratensis Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- Thecamonadinae Larsen & Patterson 1990 [Thecamonas/Chelomonas clade]

- Chelonemonas Heiss, Lee, Ishida & Simpson, 2015

- C. dolani Torruella, Galindo et al. 2022

- C. geobuk Heiss, Lee, Ishida & Simpson, 2015

- C. masanensis Heiss, Lee, Ishida & Simpson, 2015

- Thecamonas Larsen & Patterson 1990

- T. filosa Larsen & Patterson 1990 [Amastigomonas filosa (Larsen & Patterson 1990) Molina & Nerad 1991]

- T. muscula (Mylnikov 1999) Cavalier-Smith 2010 [Amastigomonas muscula Mylnikov 1999]

- T. mutabilis (Griessmann 1913) Larsen & Patterson 1990 [Rhynchomonas mutabilis Griessmann 1913; Amastigomonas mutabilis (Griessmann 1913) Patterson & Zölffel 1993]

- T. trahens Larsen & Patterson 1990 [Amastigomonas trahens (Larsen & Patterson 1990) Molina & Nerad 1991]

- Chelonemonas Heiss, Lee, Ishida & Simpson, 2015

References

- ^ a b c Karpov SA, Mylnikov AP (1989). "БИОЛОГИЯ И УЛЬТРАСТРУКТУРА БЕСЦВЕТНЫХ ЖГУТИКОНОСЦЕВ APUSOMONADIDA ORD.N" [Biology and ultrastructure of colourless flagellates Apusomonadida ord. n.] (PDF). Zoologischkeiĭ Zhurnal (in Russian). LXVIII (8): 5–17.

- ^ a b Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (May 2013). "Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and classification of the protozoan phyla Loukozoa, Sulcozoa, and Choanozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 49 (2): 115–178 Document online. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.06.001. ISSN 0932-4739. PMID 23085100.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Chao, Ema E. (October 2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of Apusomonadida (Protozoa: Apusozoa): new genera and species". Protist. 161 (4): 549–576. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2010.04.002. PMID 20537943.

- ^ Brown, Matthew W.; Sharpe, Susan C.; Silberman, Jeffrey D.; Heiss, Aaron A.; Lang, B. Franz; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Roger, Andrew J. (2013-10-22). "Phylogenomics demonstrates that breviate flagellates are related to opisthokonts and apusomonads". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1769): 20131755. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1755. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3768317. PMID 23986111.

- ^ Eme, Laura; Sharpe, Susan C.; Brown, Matthew W.; Roger, Andrew J. (2014-08-01). "On the Age of Eukaryotes: Evaluating Evidence from Fossils and Molecular Clocks". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (8): a016139. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016139. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 4107988. PMID 25085908.

- ^ a b c d e Heiss AA, Lee WJ, Ishida KI, Simpson AGB (2015). "Cultivation and Characterisation of New Species of Apusomonads (the Sister Group to Opisthokonts), Including Close Relatives of Thecamonas (Chelonemonas n. gen.)". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 62: 637–649. doi:10.1111/jeu.12220.

- ^ a b c d e f Torruella G, Galindo LJ, Moreira D, Ciobanu M, Heiss AA, Yubuki N, et al. (November 2022). "Expanding the molecular and morphological diversity of Apusomonadida, a deep-branching group of gliding bacterivorous protists". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 70 (2): e12956. doi:10.1111/jeu.12956.

- ^ Sebe-Pedros A, Roger AJ, Lang FB, King N, Ruiz-Trillo I (2010). "Ancient origin of the integrin-mediated adhesion and signaling machinery". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (22): 10142–10147. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002257107. PMC 2890464.

- ^ Sebé-Pedrós A, Ruiz-Trillo I (2010). "Integrin-mediated adhesion complex". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 3 (5): 475–477. doi:10.4161/cib.3.5.12603. PMC 2974085.

- ^ Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Agatha S, Berney C, Brown MW, Burki F, Cárdenas P, Čepička I, Chistyakova L, del Campo J, Dunthorn M, Edvardsen B, Eglit Y, Guillou L, Hampl V, Heiss AA, Hoppenrath M, James TY, Karnkowska A, Karpov S, Kim E, Kolisko M, Kudryavtsev A, Lahr DJG, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, Mann DG, Massana R, Mitchell EAD, Morrow C, Park JS, Pawlowski JW, Powell MJ, Richter DJ, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Shimano S, Spiegel FW, Torruella G, Youssef N, Zlatogursky V, Zhang Q (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Yabuki A, Tame A, Mizuno K (2022). "Podomonas kaiyoae n. sp., a novel apusomonad growing axenically". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 00: e12946. doi:10.1111/jeu.12946.