27th Infantry Division (United States)

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2012) |

| 27th Infantry Division (1917–54) 27th Armored Division (1954–67) | |

|---|---|

27th Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia. The red stars depict the Orion constellation, punning on the surname of the division's World War I commander John F. O'Ryan. The Red circle on the outside is an "O", also for "O'Ryan". The letters inside form the monogram "NYD", for "New York Division".[1][2] | |

| Active | 1917 – 1919 1921 – 1945 1946 – 1954 1954 – 1967 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Nickname(s) | "O'Ryan's Roughnecks" "New York Division" |

| Engagements | World War I Iraq War (as 27th Infantry Brigade Combat Team) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Major General John F. O'Ryan |

The 27th Infantry Division was a unit of the Army National Guard in World War I and World War II. The division traces its history from the New York Division, formed originally in 1908. The 6th Division designation was changed to the 27th Division in July 1917.[3]

History

When the New York Division was organized in 1908, New York became the second state, after Pennsylvania, to structure its National Guard at such a high tactical level in peacetime.[4] The New York Division was called to active duty during the Mexican border crisis of 1916. While on federal duty, it was redesignated as the 6th Division in June 1916. It was released from active duty in December 1916, only to be recalled for World War I service in July 1917. The 6th Division was reorganized and redesignated as the 27th Division on 1 October 1917.[5]

World War I

Formation

Following the declaration of war on the Central Powers by the United States, the division was called into federal service on 15 July 1917, and hastily recruited New Yorkers to increase its numbers.

The division was one of only four divisions formed during the war from National Guard units entirely from a single state; the other divisions so formed were from Illinois (the 33rd Division), Ohio (the 37th Division), and Pennsylvania (the 28th Division). However, not all New Yorkers served in the 27th.[6] Its initial strength was 991 officers and 27,114 enlisted men. The division's initial organization of three brigades with three infantry regiments each was carried over from the 6th Division

Prior to its departing to training, the division participated in a large send-off parade in New York City along 5th Avenue on 30 August 1917. The 7th Infantry Regiment was the first to leave for training on 11 September 1917, by train. The training was conducted at a purpose-built temporary facility at Camp Wadsworth, Spartanburg, South Carolina. Nearby hotels such as the Cleveland Hotel became centers for social life. The camp also housed seven YMCA Huts and a Knights of Columbus Hall. While the 27th had African-American service-men they were not permitted to enter the service organization clubs on base, which were segregated, until a black soldier's club was built in early 1918.[7]

In the spring of 1918, the division began its movement toward embarkation camps, and shipped out on 20 April 1918. The division's advance detachment left Hoboken on 2 May and arrived at Brest, France, 10 May 1918. Late in June the last units of the 27th Division had arrived safely overseas.

Western Front

From the arrival of the first troops to the Western Front until 24 July, the division spent its time undertaking its final stages of training under British mentors in Picardy and Flanders. On 25 July, the 27th Division, excluding its artillery brigade and ammunition train, occupied the Dickebusch Lake and Scherpenberg sectors in Flanders.

In just over a month, this operation merged into the Ypres-Lys action, and then, from 19 August to 3 September, the 27th was on its own.

It was decided by Field marshal Douglas Haig that the Fourth Army's Australian Corps would lead the Battle of St. Quentin Canal . However, due to the Corps depleted nature, which was a result of fighting almost continuously, it would be reinforced by the 27th and 30th divisions, which resulted in II Corps being temporarily reassigned under Australian command.[8] This great Somme "push", which lasted from 24 September to 1 October, saw the 27th engaged in severe fighting along the Saint Quentin Canal Tunnel—one of the out-lying strong points of the Hindenburg Line. At the conclusion of the first phase of the battle, and following heavy losses, the 27th was placed into reserve for rest and recuperation. Six days later, the division was sent back into the line, moving steadily toward Busigny whilst chasing the retreating Germans. These operations were supported by Australian Artillery until 9 October, when British artillery units began supporting the division's operations. As a result of these offensives by the Australian, British and US forces, the Hindenburg's Main Line was penetrated.

The 52d Field Artillery Brigade and the 102nd Ammunition Train of the New York Division had not gone with the rest of the Twenty-seventh Division to the British front in Flanders. They had moved up on 28 October, to support the Seventy-Ninth Division in the Argonne.

Meanwhile, the Twenty-Seventh Division units which had seen heavy action in Flanders, had moved back to an area near the French seaport of Brest.

- Major Operations: Meuse-Argonne (only the artillery), Ypres-Lys, Somme Offensive.

- Initially stationed in the East Poperinghe Line.

- Battle of Dickebusche Lake, Summer 1918

- Battle of Vierstraat Ridge, Summer 1918

- Struggled to break the German defensive Hindenburg Line, September 1918.

- Second battle of the Somme, 25 September 1918

- Selle River, November 1918

The 27th did break the Hindenburg line during the Battle of the Somme and forced a German retreat from their defensive line and forced the Germans to a final confrontation. After a final confrontation with the retreating Germans at the Selle River the Armistice ended the fighting and the division was sent home in February 1919, to be mustered out several months later.[6][9] The division had sustained a total of 8,334 (KIA: 1,442; WIA: 6,892) casualties when it was inactivated in April 1919.[10]

World War II

On 15 October 1940, the division was called into federal service, and sent to Fort McClellan, Alabama, for training. It was the first division to be deployed in the continental United States, and participated in the 1941 Louisiana Maneuvers.[11] Following the Battle of Pearl Harbor, on 14 December 1941, the division was sent to southern California.

The first stateside division to be deployed in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 27th Division departed Fort McClellan 14 December 1941 for California to establish blocking positions against an anticipated seaborne invasion of the United States southwestern coast. They were further transferred into the Pacific Theater of Operations and arrived in Hawaii, 21 May 1942, to defend the outer islands from amphibious attack. The 165th Infantry (the once and future 69th Infantry) and 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry first saw action against the enemy during the attack and capture of Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, 21–24 November 1943. The 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 106th Regiment participated in the attack on Eniwetok Atoll, 19–26 February 1944, returning to Oahu in March. During this mission, the 2nd Battalion, 106th Infantry landed unopposed on Majuro Island, 1 February, and completed its seizure, 3 February. The division began preparations for the Marianas operations, 15 March. On D-day plus 1, 16 June 1944, elements landed at night on Saipan to support the Second and Fourth Marine Divisions.[12] A beachhead was established and Aslito Airfield captured, 18 June. Fighting continued throughout June. Marine General Holland Smith, unsatisfied with the performance of the 27th Division, relieved its commander, Army General Ralph C. Smith., which led to angry recrimination from senior Army commanders, including Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. During a pitched battle, 7 July, Japanese overran elements of the division in a banzai attack, but organized resistance was crushed the next day. During the months of July and August, the 27th cleaned out isolated pockets in the mountains and cliffs of Saipan.

Beginning in the middle of August, the division moved to the New Hebrides for rest and rehabilitation. On 25 March 1945, the 27th sailed from Espiritu Santo, arriving at Okinawa, 9 April 1945. The Division participated in the XXIV Corps general attack, 19 April 1945, securing a dominating ridge line south of Machinato and Kakazu. Machinato Airfield was captured, 28 April, after a severe struggle. On 1 May, the division was relieved by the 1st Marine Division and attached to the Island Command for garrison duty. Tori Shima was seized, 12 May, without opposition. The 27th attacked from the south end of Ishikawa Isthmus to sweep the northern sector of Okinawa. The enemy fought bitterly on Onnatake Hill from 23 May until 2 June, before losing the strong point. After a mopping-up period, the division left Okinawa, 7 September 1945, moved to Japan and occupied Niigata and Fukushima Prefectures.[13]

- Overseas: 10 March 1942.

- Campaigns: Divisional elements participated in various campaigns in the Pacific Theater:

- Distinguished Unit Citations: 2.

- Awards: MH: 3; DSC: 21; DSM: 2 ; Silver Star: 412; LM: 15; SM: 13; BSM: 986; AM: 9.

- Returned to U.S.: 15 December 1945

- Inactivated: 31 December 1945

Casualties

- Total battle casualties: 6,533[14]

- Killed in action: 1,512[14]

- Wounded in action: 4,980[14]

- Missing in action: 40[14]

- Prisoner of war: 1[14]

| Unit | Campaign participation credit |

|---|---|

| Headquarters, 27th Infantry Division | Central Pacific, Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 105th Infantry Regiment | Central Pacific, Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 106th Infantry Regiment | Eastern Mandates (Ground), Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 165th Infantry Regiment | Central Pacific, Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 27th Infantry Division Artillery | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 104th Field Artillery Battalion | Eastern Mandates (Ground), Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 105th Field Artillery Battalion | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 106th Field Artillery Battalion | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 249th Field Artillery Battalion | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 102nd Engineer Combat Battalion | Central Pacific, Eastern Mandates (Ground), Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 102nd Medical Battalion | Central Pacific, Eastern Mandates (Ground), Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 27th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized) | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| Headquarters, Special Troops, 27th Infantry Division | Ryukyus |

| Headquarters Company, 27th Infantry Division | Central Pacific, Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 727th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 27th Quartermaster Company | Central Pacific, Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 27th Signal Company | Central Pacific, Eastern Mandates (Ground), Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| Military Police Platoon | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| Band | Ryukyus, Western Pacific (Ground) |

| 27th Counterintelligence Corps Detachment | Ryukyus |

Postwar

The division was reformed as a National Guard formation on 21 April 1947.[15] The division was reconstituted along the lines of its wartime structure with limited reorganizations.

In February 1955 the 27th Division became the 27th Armored Division, retaining many of its former units.

The division was reorganized in 1968 as the 27th Armored Brigade, a unit of the 50th Armored Division.[16]

The 27th Armored Brigade was reorganized as an infantry brigade in 1975 and aligned with the 42nd Infantry Division.[17]

In 1985 the 27th Infantry Brigade was activated as part of the New York Army National Guard, and assigned as the "roundout" brigade of the Army's 10th Mountain Division.[18]

The 27th Brigade was later reorganized as the 27th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, and reestablished use of the 27th Infantry Division's NYD shoulder sleeve insignia.[19] The 27th Infantry Brigade carries on the lineage and history of the 27th Infantry Division.

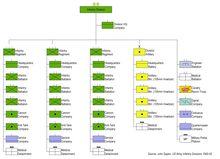

Order of battle

Chain of command deployed, WWI

- Fourth Army, British Expeditionary Force

- II Corps, American Expeditionary Force

Organization Jul – Nov 1917

- Division Headquarters

- 1st Brigade

- 7th Infantry

- 12th Infantry

- 14th Infantry

- 2d Brigade

- 1st Infantry

- 23d Infantry

- 71st Infantry

- 3d Brigade

- 2d Infantry

- 3d Infantry

- 74th Infantry

- Brigade Field Artillery

- 1st Field Artillery

- 2d Field Artillery

- 3d Field Artillery

- 1st Cavalry

- Squadron A and Machine Gun Troop

- 22d Engineers

- 1st Battalion, Signal Corps

- Trains

- Military Police[20]

- Ammunition Train

- Supply Train

- Engineer Train

- Sanitary Train

- Headquarters Ambulance Companies

- 1st Ambulance Company

- 2d Ambulance Company

- 3d Ambulance Company

- 4th Ambulance Company

- Headquarters Field Hospital

- 1st Field Hospital

- 2d Field Hospital

- 3d Field Hospital

- 4th Field Hospital

- Headquarters Ambulance Companies

- 1st Brigade

Organization from Nov 1917

Initially 3 brigades consisting of 3 infantry regiments each, for a total of nine regiments. Reorganized into 2 brigades of 2 infantry regiments each.

- Headquarters, 27th Division

- 53rd Infantry Brigade

- 105th Infantry Regiment

- 106th Infantry Regiment

- 105th Machine Gun Battalion

- 54th Infantry Brigade

- 107th Infantry Regiment

- 108th Infantry Regiment

- 106th Machine Gun Battalion

- 52nd Field Artillery Brigade

- 104th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm)

- 105th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm)

- 106th Field Artillery Regiment (155 mm)

- 102nd Trench Mortar Battery

- 104th Machine Gun Battalion

- 102nd Engineer Regiment

- 102nd Field Signal Battalion

- Headquarters Troop, 27th Division

- 102nd Train Headquarters and Military Police

- 102nd Ammunition Train

- 102nd Supply Train

- 102nd Engineer Train

- 102nd Sanitary Train

- 105th, 106th, 107th, and 108th Ambulance Companies and Field Hospitals

The artillery elements were reassigned upon arrival in France, and did not see service with the 27th Division during combat.

Organization, WWII

- Headquarters, 27th Infantry Division

- 105th Infantry Regiment

- 106th Infantry Regiment,

- 165th Infantry Regiment

- Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 27th Infantry Division Artillery

- 104th Field Artillery Battalion

- 105th Field Artillery Battalion

- 106th Field Artillery Battalion

- 249th Field Artillery Battalion

- 102nd Engineer Combat Battalion

- 102nd Medical Battalion

- 27th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

- Headquarters, Special Troops, 27th Infantry Division

- Headquarters Company, 27th Infantry Division

- 727th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

- 27th Quartermaster Company

- 27th Signal Company

- Military Police Platoon

- Band

- 27th Counterintelligence Corps Detachment

Organization, 1948 to 1954

- Division Headquarters & Headquarters Co.

- Infantry: 105th Infantry Regiment, 108th Infantry Regiment, 174th Infantry Regiment.

- Artillery: DIVARTY, 156th Field Artillery Battalion, 170th Field Artillery Battalion, 249th Field Artillery Battalion, 127th AAA Battalion (from 106th AAA, from 7th AAA, from 106th of WW2).

- Combat support: 127th Tank Battalion, 152nd Engineer Battalion, 27th Recon Troop, 27th Signal Company

- Combat service support: 27th Military Police Company, 727th Ordnance Company, 27th Quartermaster Company, 134th Medical Battalion, 27th Replacement Company.

Commanders

World War I

- Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan (16 July 1917)

- Brig. Gen. Charles L. Phillips (19 September 1917)

- Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan (6 December 1917)

- Brig. Gen. Charles L. Phillips (23 December 1917)

- Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan (29 December 1917)

- Brig. Gen. Charles L. Phillips (22 February 1918)

- Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan (1 March 1918)

- Brig. Gen. Palmer E. Pierce (16 June 1918)

- Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan (18 June 1918)

- Brig. Gen. Palmer E. Pierce (14 November 1918)

- Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan (23 November 1918)

World War II

- Maj. Gen. William N. Haskell (October 1940 – October 1941)

- Brig. Gen. Ralph McT. Pennell (November 1941 – October 1942)

- Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith (November 1942 – May 1944)

- Maj. Gen. George W. Griner Jr. (June 1944 – December 1945)

References

- ^ Hart, Albert Bushnell (1920). Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War, Volume 5. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 358.

- ^ Moss, James Alfred; Howland, Harry Samuel (1920). America in Battle: With Guide to the American Battlefields in France and Belgium. Menasha, Wisconsin: Geo. Banta Publishing Co. p. 555.

- ^ Wilson, John B. (1998). Maneuver and Firepower: Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 60-14. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ National Guard Education Foundation

- ^ However, the Combat Chronicles give the date of the redesignation as the 27th as 20 July 1917.

- ^ a b "27th Division World War One". Unit History Project. New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Chapter 7 Fighting Boredom: Life at Camp Wadsworth". Tent and Trench. Spartanburg County Historical Association. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Cameron 2018.

- ^ "Why My Ancestors Fought in the Civil War". 29 April 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Star Performers 27th Division World War One". Unit History Project. New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ @usacac (23 November 2021). "pearl harbor" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Goldberg, Harold J. (2007). D-day in the Pacific: The Battle of Saipan. Indiana University Press. pp. 112. ISBN 978-0-253-34869-2.

- ^ The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1950. pp. 510–92. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ^ "27th Armored Division". National Guard Education Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Guard Streamlined: 27th Division Enddate=18 January 1968". Associated Press, Newburgh Evening News.

- ^ McGrath, John J. (2009). The Brigade: A History, Its Organization and Employment in the US Army. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4289-1022-5.

- ^ Doubler, Michael Dale; Listman, John W. Jr. (2007). The National Guard: An Illustrated History of America's Citizen-Soldiers. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-57488-389-3.

- ^ 2008 National Guard Almanac. Uniformed Services Almanacs. 2008. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-888096-13-2.

- ^ 1919 History of 102nd M.P.

Bibliography

- Cameron, David W. (2018). Australians on the Western Front: 1918. Vol. 2. Penguin Random House Australia. pp. 387–436. ISBN 978-0-670-07828-8.

Further reading

- Love, Edmund G. (1982). The 27th Infantry Division in World War II. Battery Press. ISBN 978-0-89839-056-8.

- Gailey, Harry A. (1986). Howlin' Mad Vs. the Army: Conflict in Command, Saipan 1944. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-242-5.

- Swetland, Maurice J., and Lilli Swetland. "These Men": "For Conspicuous Bravery Above and Beyond the Call of Duty ...". [Harrisburg, Pa.]: Military Service Pub. Co, 1940. OCLC 3505183

- Mitchell A. Yockelson, Borrowed Soldiers: Americans under British Command, 1918, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-8061-3919-7.

External links

- Pictorial History of the 27th Division, United States Army, 1940–1941 – New York State Military Museum on New York Heritage Digital Collections

- O'Ryan's Roughnecks

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army

- United States Army divisions during World War II

- Divisions of the United States Army National Guard

- United States Army divisions of World War I

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army in World War II

- Military units and formations established in 1917

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1967