Pavel Florensky

Pavel Florensky | |

|---|---|

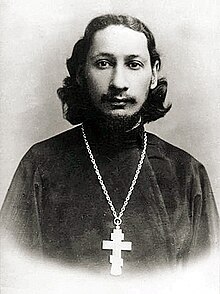

Father Pavel Florensky | |

| Born | Pavel Alexandrovich Florensky 21 January 1882 |

| Died | 8 December 1937 (aged 55) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy |

| School | Christian philosophy Sophiology |

| Academic advisors | Nikolai Bugaev |

Main interests | Philosophy of religion |

Pavel Alexandrovich Florensky (also P. A. Florenskiĭ, Florenskii, Florenskij; Russian: Па́вел Алекса́ндрович Флоре́нский; Armenian: Պավել Ֆլորենսկի, romanized: Pavel Florenski; 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1882 – December 8, 1937) was a Russian Orthodox theologian, priest, philosopher, mathematician, physicist, electrical engineer, inventor, polymath, neomartyr and folk saint.[1] During the later twentieth century, statements had appeared noting a recognition by the Russian Orthodox Church of him as a saint, though it was later firmly noted that no such decision had been made.[2]

Biography

Early life

Pavel Aleksandrovich Florensky was born on 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1882 in the town of Yevlakh in Elisabethpol Governorate (in present-day western Azerbaijan) into the family of a railroad engineer, Aleksandr Florensky. His father came from a family of Russian Orthodox priests while his mother Olga (Salomia) Saparova (Saparyan, Sapharashvili) was of the Tbilisi Armenian nobility in Georgia.[3][4][5] His maternal grandmother Sofia Paatova (Paatashvili) was from an Armenian family from Karabakh, living in Bolnisi, Georgia.[6] Florensky "always searched for the roots of his Armenian family" and noted that they came from Karabakh.[7]

Florensky completed his high school studies (1893-1899) at the Tbilisi classical lyceum, where several companions were later to distinguish themselves, among them the founder of Russian Cubo-Futurism, David Burliuk. In 1899, Florensky underwent a religious crisis, connected to a visit to Leo Tolstoy caused by an awareness of the limits and relativity of the scientific positivism and rationality which had been an integral part of his initial formation within his family and high school. He decided to construct his own solution by developing theories that would reconcile the spiritual and the scientific visions on the basis of mathematics. He entered the department of mathematics of the Imperial Moscow University and studied under Nikolai Bugaev, and became friends with his son, the future poet and theorist of Russian symbolism, Andrei Bely. He was particularly drawn to Georg Cantor's set theory.[3]

He also took courses on ancient philosophy. During this period the young Florensky, who had no religious upbringing, began taking an interest in studies beyond "the limitations of physical knowledge"[8] In 1904 he graduated from the Imperial Moscow University and declined a teaching position at the university: instead, he proceeded to study theology at the Ecclesiastical Academy in Sergiyev Posad. During his theological studies there, he came into contact with Elder Isidore on a visit to Gethsemane Hermitage, and Isidore was to become his spiritual guide and father. Together with fellow students Ern, Svenitsky and Brikhnichev he founded a society, the Christian Struggle Union (Союз Христиaнской Борьбы), with the revolutionary aim of rebuilding Russian society according to the principles of Vladimir Solovyov. Subsequently he was arrested for membership in this society in 1906: however, he later lost his interest in the Radical Christianity movement.

Intellectual interests

During his studies at the Ecclesiastical Academy, Florensky's interests included philosophy, religion, art and folklore. He became a prominent member of the Russian Symbolism movement, together with his friend Andrei Bely and published works in the magazines New Way (Новый Путь) and Libra (Весы). He also started his main philosophical work, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. The complete book was published only in 1914 but most of it was finished at the time of his graduation from the academy in 1908.

According to the forward in a book of his letters published by the Princeton University Press: "The book is a series of twelve letters to a 'brother' or 'friend,' who may be understood symbolically as Christ. Central to Florensky's work is an exploration of the various meanings of Christian love, which is viewed as a combination of philia (friendship) and agape (universal love). He describes the ancient Christian rites of the adelphopoiesis (brother-making), which joins male friends in chaste bonds of love. In addition, Florensky was one of the first thinkers in the twentieth century to develop the idea of the Divine Sophia, who has become one of the central concerns of feminist theologians."[9]

Recent research by Michael Hagemeister, known mostly for his work on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, has authenticated that antisemitic material, written under a pseudonym, is in Florensky's hand. Florensky's biographer Avril Pyman evaluates Florensky's position regarding Jews as, contextually for the period, a middle way between liberal critics who excoriated at the time of the incident Russia's backwardness and the behaviour of instigators of pogroms like the Black Hundreds.

After graduating from the academy, he married Anna Giatsintova, the sister of a friend, in August 1910, a move which shocked his friends who were familiar with his aversion to marriage.[10] He continued to teach philosophy and lived at Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra until 1919. In 1911 he was ordained into the priesthood. In 1914 he wrote his dissertation, About Spiritual Truth. He published works on philosophy, theology, art theory, mathematics and electrodynamics. Between 1911 and 1917 he was the chief editor of the most authoritative Orthodox theological publication of that time, Bogoslovskiy Vestnik. He was also a spiritual teacher of the controversial Russian writer Vasily Rozanov, urging him to reconcile with the Orthodox Church.

Period of Communist rule in Russia

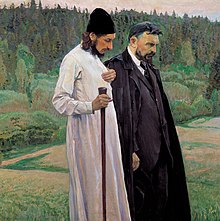

After the October Revolution he formulated his position as: "I have developed my own philosophical and scientific worldview, which, though it contradicts the vulgar interpretation of communism... does not prevent me from honestly working in the service of the state." After the Bolsheviks closed the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra (1918) and the Sergievo-Posad Church (1921), where he was the priest, he moved to Moscow to work on the State Plan for Electrification of Russia (ГОЭЛРО) under the recommendation of Leon Trotsky who strongly believed in Florensky's ability to help the government in the electrification of rural Russia. According to contemporaries, Florensky in his priest's cassock, working alongside other leaders of a Government department, was a remarkable sight.

In 1924, he published a large monograph on dielectrics. He worked simultaneously as the Scientific Secretary of the Historical Commission on Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra and published his works on ancient Russian art. He was rumoured to be the main organizer of a secret endeavour to save the relics of St. Sergii Radonezhsky whose destruction had been ordered by the government.

In the second half of the 1920s, he mostly worked on physics and electrodynamics, eventually publishing his paper Imaginary numbers in Geometry («Мнимости в геометрии. Расширение области двухмерных образов геометрии») devoted to the geometrical interpretation of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity. Among other things, he proclaimed that the geometry of imaginary numbers predicted by the theory of relativity for a body moving faster than light is the geometry of the Kingdom of God. For mentioning the Kingdom of God in that work, he was accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda by Soviet authorities.

1928–1937: exile, imprisonment, death

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to Nizhny Novgorod. After the intercession of Ekaterina Peshkova (wife of Maxim Gorky), Florensky was allowed to return to Moscow. On 26 February 1933 he was arrested again, on suspicion of engaging in a conspiracy with Pavel Gidiulianov, a professor of canon law who was a complete stranger to Florensky, to overthrow the state and install, with Nazi assistance, a fascist monarchy.[11] He defended himself vigorously against the imputations until he realized that by showing a willingness to admit them, though false, he would enable several acquaintances to resecure their liberty. He was sentenced to ten years in the labor camps by the infamous Article 58 of Joseph Stalin's criminal code (clauses ten and eleven: "agitation against the Soviet system" and "publishing agitation materials against the Soviet system"). The published agitation materials were the monograph about the theory of relativity.[citation needed][dubious – discuss] His manner of continuing to wear priestly garb annoyed his employers. The state offered him numerous opportunities to go into exile in Paris, but he declined them.

He served at the Baikal Amur Mainline camp until 1934 when he was moved to Solovki, where he conducted research into producing iodine and agar out of the local seaweed. In 1937 he was transferred to Saint Petersburg (then known as Leningrad) where, on 25 November, he was sentenced by an extrajudicial NKVD troika to death. According to a legend he was sentenced for the refusal to disclose the location of the head of St. Sergii Radonezhsky that the communists wanted to destroy. The saint's head was indeed saved and in 1946 the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra was opened again. The relics of St. Sergii became fashionable once more. The saint's relics were returned to Lavra by Pavel Golubtsov, later known as Archbishop Sergiy.[citation needed]

After sentencing, Florensky was transported in a special train together with another 500 prisoners to a location near St. Petersburg, where he was shot dead on the night of 8 December 1937 in a wood not far from the city. The site of his burial is unknown. Antonio Maccioni states that he was shot at the Rzhevsky Artillery Range, near Toksovo, which is located about twenty kilometers northeast of Saint Petersburg and was buried in a secret grave in Koirangakangas near Toksovo together with 30,000 others who were executed by the NKVD at the same time.[12] In 1997, a mass burial ditch was excavated in the Sandarmokh forest, which may well contain his remains. His name was registered in 1982 among the list of New Martyrs and Confessors.[13]

He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1958 (of the 1933 charges) and 1959 (of the 1937 charges.)

Influence

Florensky, often read for his contributions to the religious renaissance of his time or scientific thinking, came to be studied in a broader perspective in the 1960s, a change associated with the revival of interest in neglected aspects of his oeuvre shown by the Tartu school of semiotics, which evaluated his works in terms of their anticipation of themes that formed part of the theoretical avant-garde's interests in a general theory of cultural signs at that time. Read in this light, the evidence that Florensky's thinking actively responded to the art of the Russian modernists. Of particular importance in this regard was their publication of his 1919 essay, delivered as a lecture the following year, on spatial organization in the Russian icon tradition, entitled "Reverse Perspective",[14] a concept which Florensky, like Erwin Panofsky later, picked up from Oskar Wulff's 1907 essay, 'Die umgekehrte Perspektive und die Niedersicht.[15] Here Florensky contrasted the dominant concept of spatiality in Renaissance art analysing the visual conventions employed in the iconological tradition. This work has remained since its publication a seminal text in this area down to the present day. In that essay,[16] his interpretation has recently been developed and reformulated critically by Clemena Antonova, who argues rather that what Florensky analysed is better described in terms of "simultaneous planes".[17][18]

See also

References

- ^ Flight from Eden

- ^ The Orthodox Messenger, Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, No. 30/31, pp. 5/6

- ^ a b Natalino Valentini, (ed.) Pavel Florenskij, La colonna e il fondamento della verità, San Paolo editore, 2010, p. lxxi.

- ^ Oleg Kolesnikov. "Pavel Florensky" (in Russian).

- ^ Pavel V. Florensky; Tatiana Shutova. "Pavel Florensky". Nashe Nasledie (in Russian)

- ^ Novoe vremya, 01/02/2018

- ^ Леонид Фридович Кацис, Кровавый навет и русская мысль: историко-теологическое исследование дела Бейлиса, Мосты культуры, 2006, 494 c., c. 389.

- ^ Salt of the Earth by Pavel Florensky

- ^ The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. Princeton University Press. 21 March 2004. ISBN 9780691117676.

- ^ Avril Pyman, Pavel Florensky: A Quiet Genius: The Tragic and Extraordinary Life of Russia's Unknown da Vinci, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010 p.86.

- ^ Avril Pyman, pp. 154ff.

- ^ Antonio Maccioni, "Pavel Aleksandrovič Florenskij. Note in margine all'ultima ricezione italiana", eSamizdat, 2007, V (1-2), pp. 471-478 Antonio Maccioni. "Pavel Aleksandrovic Florenskij" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ Natalino Valentini. Pavel A. Florenskij, San Paolo editore, Milan 2010 p.lxxxii.

- ^ Pavel Florensky (Nicoletta Misler ed.), Beyond Vision: Essays on the Perception of Art, Reaktion Books 2006 pp.197-272

- ^ Marcus Plested, Orthodox Readings of Aquinas, Oxford University Press 2012 p.9 and n.1.

- ^ Clemena Antonova, 'Changing prceptions of Pavel Florensky in Russian and Soviet Scholarship,' in Costica Bradatan, Serguei Oushakine (eds.) In Marx's Shadow: Knowledge, Power, and Intellectuals in Eastern Europe and Russia, Lexington Books, 2010 pp.73-94 pp.80, 82-83

- ^ Clemena Antonova, Space, Time, and Presence in the Icon: Seeing the World with the Eyes of God, Routledge, 2016 p.169.

- ^ Matthew J. Milliner, 'Icons as Theology:The Virgin Mary of Predestination,' in James Romaine, Linda Stratford (eds.)ReVisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art, The Lutterworth Press, 2014 pp.73-94 p.86.

External links

Biographies

- (in Russian) Site devoted to Florensky

- (in Russian) Biography

- (in Russian) Hagiography

- (in Italian) Biography, by Abate Herman and Padre Damascene

Works

- The Pavel Florensky School of Theology and Ministry

- (in Italian) DISF: P.A. Florenskij - Voice by N. Valentini

- (in Italian) Paper about some Florenskij's book

- (in Italian) Florenskij in Italy - Article by A. Maccioni

- (in Greek) Page devoted to Florenskij

- Florensky, Pavel (2004). The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11767-6.[permanent dead link]

- Florensky, Pavel (1999-02-13). Salt of the Earth (The Acquisition of the Holy Spirit in Russia Series. Vol. 2. Saint Herman Press. ISBN 0-938635-72-7.

- Florensky, Pavel (1922). Mnimosti in Geometry. Pomor'ye.

- Florensky, Pavel (1996). Iconostasis. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 0-88141-117-5.

- Florensky, Pavel (2006-08-15). Beyond Vision: Essays on the Perception of Art. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-307-9.

- Florensky, Pavel. "Onomatodoxy as a Philosophical Premise (excerpts)". A. F. Losev page. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- "Pavel Florensky on Brotherhood Rite". Gay.ru. Russian National GLBT Center. Archived from the original (translated from Russian by Fr. German Ciuba) on 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Titova, Irina (2002-10-01). "'Russian da Vinci' May Be Among Remains". St. Petersburg Times. p. 73. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- "Pavel Florensky's House - Sergiev Posad". Golden Ring of Russia. 2007-02-14. Archived from the original on 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Leach, Joseph H. J. (Fall 2006). "Parallel Visions - A consideration of the work of Pavel Florensky and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin". Theandros. 4 (1). Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Rhodes, Michael C. (Spring 2005). "Logical Proof of Antinomy: A Trinitarian Interpretation of the Law of Identity". Theandros. 2 (3). Archived from the original on 2005-06-21. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Berdyaev, Nikolai (February 1917). "Khomyakov and Fr. Florensky" (reprint, translation from Russian). Journal Russkaya Mysl (257). Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Steineger IV, Joseph E. (Spring–Summer 2006). "Cult, Rite, and the Tragic: Appropriating Nietzsche's Dionysian with Florenskii's Titanic". Theandros. 3 (3). Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Bird, Robert. "The Geology of Memory: Pavel Florensky's Hermeneutic Theology". equestrial.ru. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Seiling, Jonathan (September 2005). "Kant's Third Antinomy and Spinoza's Substance in the Sophiology of Florenskii and Bulgakov". Florensky Conference. Archived from the original (RTF document) on 2009-10-27. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Reardon, Patrick Henry (1998-09-01). "Truth Is Not Known Unless It Is Loved: How Pavel Florensky restored what Ockham stole". Books & Culture. Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- Dvoretskaya, Ekaterina. "Personal approach to Symbolic reality". crvp.org. Council for Research and Values in Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- (in Italian) Template:Curlie

- 1882 births

- 1937 deaths

- 20th-century Christian mystics

- 20th-century Eastern Orthodox martyrs

- 20th-century Eastern Orthodox theologians

- 20th-century Russian philosophers

- 20th-century Russian scientists

- Eastern Orthodox mystics

- Critics of atheism

- Eastern Orthodox philosophers

- Eastern Orthodox theologians

- Executed priests

- Bamlag detainees

- Great Purge victims from Azerbaijan

- Armenian people from the Russian Empire

- Engineers from the Russian Empire

- Inventors from the Russian Empire

- Mathematicians from the Russian Empire

- Philosophers from the Russian Empire

- Religious leaders from the Russian Empire

- Theologians from the Russian Empire

- Imperial Moscow University alumni

- People executed by the Soviet Union

- People from Elizavetpol Governorate

- People from Yevlakh

- Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians

- Russian Christian mystics

- Russian people of Armenian descent

- Sophiology

- Soviet inventors

- Soviet rehabilitations

- Soviet theologians

- Inmates of Solovki prison camp