Classical physics

Classical physics is a group of physics theories that predate modern, more complete, or more widely applicable theories. If a currently accepted theory is considered to be modern, and its introduction represented a major paradigm shift, then the previous theories, or new theories based on the older paradigm, will often be referred to as belonging to the area of "classical physics".

As such, the definition of a classical theory depends on context. Classical physical concepts are often used when modern theories are unnecessarily complex for a particular situation. Most often, classical physics refers to pre-1900 physics, while modern physics refers to post-1900 physics, which incorporates elements of quantum mechanics and relativity.[1]

Overview

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

Classical theory has at least two distinct meanings in physics. In the context of quantum mechanics, classical theory refers to theories of physics that do not use the quantisation paradigm, which includes classical mechanics and relativity.[2] Likewise, classical field theories, such as general relativity and classical electromagnetism, are those that do not use quantum mechanics.[3] In the context of general and special relativity, classical theories are those that obey Galilean relativity.[4]

Depending on point of view, among the branches of theory sometimes included in classical physics are variably:

- Classical mechanics

- Newton's laws of motion

- Classical Lagrangian and Hamiltonian formalisms

- Classical electrodynamics (Maxwell's Equations)

- Classical thermodynamics

- Classical chaos theory and nonlinear dynamics

Comparison with modern physics

In contrast to classical physics, "modern physics" is a slightly looser term that may refer to just quantum physics or to 20th- and 21st-century physics in general. Modern physics includes quantum theory and relativity, when applicable.

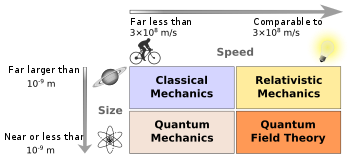

A physical system can be described by classical physics when it satisfies conditions such that the laws of classical physics are approximately valid.

In practice, physical objects ranging from those larger than atoms and molecules, to objects in the macroscopic and astronomical realm, can be well-described (understood) with classical mechanics. Beginning at the atomic level and lower, the laws of classical physics break down and generally do not provide a correct description of nature. Electromagnetic fields and forces can be described well by classical electrodynamics at length scales and field strengths large enough that quantum mechanical effects are negligible. Unlike quantum physics, classical physics is generally characterized by the principle of complete determinism, although deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics do exist.

From the point of view of classical physics as being non-relativistic physics, the predictions of general and special relativity are significantly different from those of classical theories, particularly concerning the passage of time, the geometry of space, the motion of bodies in free fall, and the propagation of light. Traditionally, light was reconciled with classical mechanics by assuming the existence of a stationary medium through which light propagated, the luminiferous aether, which was later shown not to exist.

Mathematically, classical physics equations are those in which Planck's constant does not appear. According to the correspondence principle and Ehrenfest's theorem, as a system becomes larger or more massive the classical dynamics tends to emerge, with some exceptions, such as superfluidity. This is why we can usually ignore quantum mechanics when dealing with everyday objects and the classical description will suffice. However, one of the most vigorous ongoing fields of research in physics is classical-quantum correspondence. This field of research is concerned with the discovery of how the laws of quantum physics give rise to classical physics found at the limit of the large scales of the classical level.

Computer modeling and manual calculation, modern and classic comparison

Today, a computer performs millions of arithmetic operations in seconds to solve a classical differential equation, while Newton (one of the fathers of the differential calculus) would take hours to solve the same equation by manual calculation, even if he were the discoverer of that particular equation.

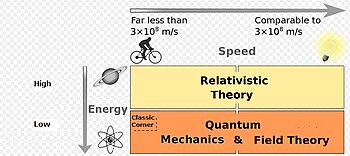

Computer modeling is essential for quantum and relativistic physics. Classical physics is considered the limit of quantum mechanics for a large number of particles. On the other hand, classic mechanics is derived from relativistic mechanics. For example, in many formulations from special relativity, a correction factor (v/c)2 appears, where v is the velocity of the object and c is the speed of light. For velocities much smaller than that of light, one can neglect the terms with c2 and higher that appear. These formulas then reduce to the standard definitions of Newtonian kinetic energy and momentum. This is as it should be, for special relativity must agree with Newtonian mechanics at low velocities. Computer modeling has to be as real as possible. Classical physics would introduce an error as in the superfluidity case. In order to produce reliable models of the world, one can not use classical physics. It is true that quantum theories consume time and computer resources, and the equations of classical physics could be resorted to in order to provide a quick solution, but such a solution would lack reliability.

Computer modeling would use only the energy criteria to determine which theory to use: relativity or quantum theory, when attempting to describe the behavior of an object. A physicist would use a classical model to provide an approximation before more exacting models are applied and those calculations proceed.

In a computer model, there is no need to use the speed of the object if classical physics is excluded. Low-energy objects would be handled by quantum theory and high-energy objects by relativity theory.[5][6][7]

See also

References

- ^ Weidner and Sells, Elementary Modern Physics Preface p.iii, 1968

- ^ Morin, David (2008). Introduction to Classical Mechanics. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521876223.

- ^ Barut, Asim O. (1980) [1964]. "Introduction to Classical Mechanics". Electrodynamics and Classical Theory of Fields & Particles. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486640389.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (2004) [1920]. Relativity. Robert W. Lawson. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 9780760759219.

- ^ Wojciech H. Zurek, Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical, Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715 or arXiv:quant-ph/0105127

- ^ Wojciech H. Zurek, Decoherence and the transition from quantum to classical, Physics Today, 44, pp 36–44 (1991)

- ^ Wojciech H. Zurek: Decoherence and the Transition from Quantum to Classical—Revisited Los Alamos Science Number 27 2002