Battle of Fairfax Court House (1863)

38°51′9″N 77°18′15″W / 38.85250°N 77.30417°W

| Skirmish at Fairfax Court House (June 1863) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

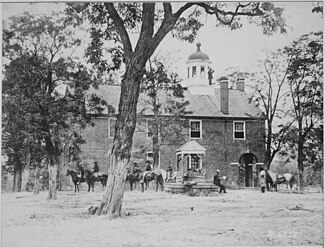

Fairfax Court House, Virginia by Matthew Brady From U.S. National Archives | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Major Seth Pierre Remington |

Major General J.E.B. Stuart Brigadier General Wade Hampton III Major John H. Whitaker † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 87[1] | 2,000[2][3][4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4 killed, 14 wounded and captured, 19 captured and 4 seriously wounded and left at a nearby home[5] | 5 killed, unknown wounded, 14 initial prisoners rescued[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Fairfax Court House (June 1863) was fought during the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War between two cavalry detachments from the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by General Joseph Hooker, and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee.

The Confederate cavalry leader General J.E.B. Stuart was keen to restore his prestige after two humiliating encounters with Union cavalry, and as the main body crossed the Potomac into Maryland, he received permission to detach three brigades and ride around the entire Union army to gather supplies and intelligence, and damage lines of communication.

At Fairfax Court House, Virginia, on 27 June, one of Stuart’s brigades, led by Brigadier General Wade Hampton, was surprised by a small detachment of the 11th New York Cavalry under Major Remington, which initially drove them into the woods, but were so heavily outnumbered that they had to retreat. Although technically a Confederate win, this small engagement had a major impact on the outcome of Gettysburg, since it delayed Stuart’s arrival, depriving Lee of essential knowledge of the enemy’s whereabouts.

Background

Plan to invade the North

On the night of May 5–6, 1863, after the Army of the Potomac commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker had been defeated at the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 30, 1863 to May 6, 1863), in Spotsylvania County, Virginia by the General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, Hooker withdrew his forces to positions north of the Rappahannock River, mainly in the vicinity of Falmouth, Virginia. Lee's army remained just to the south of the Rappahannock in the Fredericksburg, Virginia area after the battle.[6]

Meanwhile, in Mississippi, Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant was closing in on a Confederate army at Vicksburg, Mississippi.[7] Loss of Vicksburg would give the Union control of the Mississippi River and effectively cut off Confederate territory west of the Mississippi from the rest of the Confederacy.[8][9] Leaders of the Confederate government, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate States Secretary of War James A. Seddon wanted to relieve the pressure on Vicksburg, possibly by sending reinforcements from Virginia to Mississippi or to Tennessee in order to divert attention of Union forces from Vicksburg.[10]

In meetings with Davis and Seddon from May 14, 1863 to May 17, 1863 and on May 26, 1863, Lee proposed to relieve the pressure in Mississippi by diverting Union Army attention to an invasion of the North from Virginia.[11][12] This also would spare Virginia from further campaigning that summer, allow the Army of Northern Virginia to live off the land in the North and to threaten major cities, such as Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in order to weaken Northern support for the war and possibly even to obtain foreign recognition of the Confederacy.[11][12][13] Davis and Seddon, along with Davis's entire cabinet, except Postmaster-General John Reagan of Texas, agreed upon Lee's plan at these meetings.[12][14] However, further correspondence was exchanged, which made it appear to some later historians that Davis's full approval did not come until May 31.[14] On the other hand, historian Stephen W. Sears states that the further correspondence only concerned Lee's difficulty with D. H. Hill concerning reinforcements and not the plan to invade the North and that Lee began to get his force ready to move north on May 17.[15]

Lee completed a reorganization of his army by June 1, 1863 and began preparations to move to Virginia's Shenandoah Valley and then into Maryland and Pennsylvania.[16] By June 2, 1863, Lee had intelligence that Union forces along the Virginia coast and on the Virginia Peninsula were not contemplating a move against Richmond, Virginia, the Confederacy's capital and that Hooker was not prepared to make another strike across the Rappahannock.[17]

Beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign

The Confederate Gettysburg Campaign began on June 3, 1863 with the Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, under its new commander, Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, moving northwest from the Fredericksburg area to Culpeper Court House, Virginia.[17][18] By the next day, Hooker learned of the Confederate movement but did not know whether Lee was attempting to move north or to attack Hooker's right flank or whether the Confederates were moving their infantry or just cavalry.[19] Hooker proposed to attack Lieutenant General A. P. Hill's Third Corps at Fredericksburg but President Abraham Lincoln and Union Army General-in-Chief Henry Halleck thought that the plan was too risky and would enable Lee to turn his force at Culpeper to attack Hooker's flank, possibly while Hooker's men were engaged in crossing the Rappahannock.[20] Hooker gave up the idea.[20]

On June 6, 1863, Union Brigadier General John Buford informed Hooker that Lee's "movable" force, consisting of six brigades of cavalry, was at Culpeper.[21] Buford did not know about the presence of Ewell's Second Corps and two of James Longstreet's First Corps divisions at Culpeper.[21]

Battle of Brandy Station

On June 7, acting on Buford's intelligence, Hooker ordered Major General Alfred Pleasonton to take his entire cavalry corps and 3,000 infantrymen, a combined force of about 11,000 men including artillerymen, across the Rappahannock River near Brandy Station, Virginia and "disperse and destroy" the Confederate force at Culpeper.[21] At dawn on June 9, 1863, Pleasonton's force, divided into two wings commanded by Brigadier General John Buford and Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg, crossed the Rappahannock at Beverly Ford and Kelly's Ford, about 5.5 miles (8.9 km) apart.[22][23] They planned to unite at Brandy Station about 4 miles (6.4 km) from Beverly Ford and 8 miles (13 km) from Kelly's Ford and then to move 6 miles (9.7 km) west to Culpeper.[22] Buford's wing drove the Confederate pickets from Beverly Ford and surprised the Confederate cavalry camped nearby around Fleetwood Hill, where Stuart had his headquarters, and Brandy Station.[24] The Battle of Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the war, continued until late afternoon with the Confederates ultimately holding Fleetwood Hill.[25][26] With Confederate infantry approaching the area, Pleasonton made an orderly withdrawal across the Rappahannock.[25] Stuart called the battle a victory but he was subjected to criticism for being surprised and for the losses inflicted on his men by Pleasonton's force.[27][28][29] To Stuart's chagrin, for the first time in the war, the Union cavalry came out of a battle with the Confederate cavalry on roughly even terms.[30]

Troop movements and cavalry actions

Between June 9 and June 15, 1863, Lee contended with Davis and Seddon, and with the commander of Confederate forces in North Carolina and Southeast Virginia, Major General Daniel Harvey Hill, about the number and veteran status of the units to be left behind to guard Richmond and the coastal areas of Virginia and North Carolina.[31] On June 15, Lee began to concentrate his entire army for the offensive.[32] He had already ordered Ewell to proceed with the Second Corp to the Shenandoah Valley on June 10.[33]

After the Battle of Brandy Station, Hooker was persuaded by Pleasonton that Confederate infantry were at Culpeper and began to move his corps to the west, eventually spreading the Army of the Potomac over a 40 miles (64 km) line from Fredericksburg to Beverly Ford.[32] On June 13, Hooker heard that the First Corps and Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia were headed toward the Shenandoah Valley.[34] On June 14, he ordered the right wing of his army to concentrate at Manassas Junction, Virginia and the left wing to go to Dumfries, Virginia after withdrawing government property from depots north of Fredericksburg, especially the base at Aquia Creek.[35] Hooker moved his headquarters to Dumfries and then to Fairfax Station and then to Fairfax Court House.[36][37] By leaving the Fredericksburg line, Hooker enabled Lee to order Hill to go to Culpeper and Longstreet to proceed to the Shenandoah Valley without concern that Hooker would try to cross the Rappahannock and make a strike toward Richmond.[36]

Two Confederate cavalry brigades under William E. Jones ("Grumble" Jones) and Wade Hampton III[38] screened the movement of A. P. Hill's Corps to Culpeper.[36] The Confederate and Union forces, mostly cavalry, fought daily in the Loudoun Valley area between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Bull Run Mountains during the week after June 17, 1863 as the two armies tried to learn each other's positions and movements or to prevent their opposition from gathering such information about their own forces.[36] Although the Confederates kept the Union cavalry east of the Blue Ridge, Pleasanton and Gregg concluded that only Confederate cavalry was east of the Blue Ridge when in fact Longstreet's corps was spread out east of the mountains for some days that week.[39]

Battle of Upperville

With Hooker's permission, on June 21, Pleasonton left two infantry brigades at Middleburg to guard his line of communications and took five cavalry brigades and Colonel (United States) Strong Vincent's infantry brigade to attack Stuart's five cavalry brigades near Upperville, Virginia.[39] At the Battle of Upperville, Pleasonton's force drove Stuart's five brigades from the town and into Ashby's Gap.[39] Pleasonton was satisfied with this result and did not try to push Stuart across the mountains.[39] Stuart had kept Pleasonton from finding the Confederate infantry.[39] Near nightfall, however, Brigadier General John Buford's scouts rode up a nearby ridge and spied Confederate infantry camps in the Shenandoah Valley.[40] The minor Union victory at Upperville which resulted in the capture of one or two Confederate artillery pieces and about 250 Confederate prisoners also resulted in gathering some useful intelligence about the disposition of part of Lee's infantry[39] The action also delayed the march of two infantry divisions of Lee's army in order for the Confederates to be sure to hold Ashby's Gap and to have a force available at Shepherdstown, West Virginia if Union troops moved toward the Shenandoah Valley and were able to break through.[39] Stuart again came in for criticism in Southern newspapers for being surprised and defeated at Upperville.[41]

Lee soon learned that Pleasonton had withdrawn to Aldie, Virginia.[42] He then knew he could leave the heavily reinforced positions in Virginia and hasten his movement into Maryland and Pennsylvania.[43] Ewell's corps, with Albert G. Jenkins's cavalry brigade were to march toward the Susquehanna River to gather food and supplies.[42] Lee ordered Brigadier General John D. Imboden to lead his cavalry brigade across the Potomac to join Ewell's corps if opportunity offered, but Imboden decided he did not have that opportunity and stayed behind.[43]

Beginning of Stuart's ride

Stuart now sought to take a useful role in the campaign and perhaps, according to some historians, to redeem his reputation and to secure the glory of another ride around the Union Army.[44][45] On June 22, Lee gave Stuart discretionary orders for his movement to Pennsylvania with the important point being: "If you find that he [the enemy] is moving northward, and that two brigades can guard the Blue Ridge and take care of your rear, you can move with the other three into Maryland, and take position on General Ewell's right."[46] Lee wrote to Stuart again on June 23 in an apparent effort to clarify his orders as follows: "You will, however, be able to judge whether you can pass around their Army without hindrance, doing them all the damage you can, and cross the river east of the mountains. In either case, after crossing the river, you must move on and feel the right of Ewell's troops."[46] Lee's orders did not give Stuart a specific route to follow.[47] Confederate Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, chief of artillery of Longstreet's corps, stated "Stuart made to Lee a very unwise proposition, which Lee more unwisely entertained."[48]

Major John S. Mosby, scouting for Stuart with a small group of partisan rangers, told Stuart that Stuart could cut through the separated Union corps, cross the Potomac at Seneca Ford, 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Washington, D.C., and disrupt Hooker's communications and supplies, possibly even divert his army toward the defense of Washington.[49] Stuart was eager to restore his reputation after being surprised and evenly fought at Brandy Station and Upperville.[37][49] After Mosby reported that Hooker did not seem to be moving, on June 24 Stuart used the discretion in his orders to follow Mosby's advice and attempt to ride through and around the Union Army and, as he said thereafter, to meet Ewell at York, Pennsylvania.[50][51] Historian Edwin B. Coddington said the directive to damage the Union forces on the way was an invitation to delay.[52] Taking his three most experienced brigades under Brigadier Generals Wade Hampton, III and Fitzhugh Lee and Colonel John R. Chambliss, Jr. in temporary command of W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee's brigade because Lee had been wounded, Stuart left the brigades of Brigadier Generals Beverly Robertson and "Grumble" Jones with all but one of his artillery batteries to guard the mountain passes and to catch up with the infantry after the Union forces had departed.[52][53]

After spending June 24 in preparation and concentrating his forces at Salem, now Marshall, Virginia, Stuart started for Haymarket, Virginia by way of Glasscock Gap in the Bull Run Mountains on June 25.[54][55] Before reaching his objective, Stuart ran into Union Major General Winfield Scott Hancock's II corps.[54][56] Stuart fired a few artillery shells, then withdrew, sent Fitzhugh Lee's brigade to Gainesville, Virginia and stopped at Buckland, Virginia with his other two brigades in order to allow his horses to graze as they had no forage.[54][57] The incident with Hancock's corps prevented Stuart from meeting again with Mosby.[58] Instead of turning back to catch up with the infantry as quickly as possible, Stuart waited for Mosby for ten hours on June 26, then marched for 20 miles (32 km) and again grazed his horses near Wolf Run Shoals on the Occoquan River before moving on toward Fairfax Station early on June 27.[59][60]

Battle

Reconnaissance of the 11th New York Cavalry

On June 26, 1863, the U.S. War Department ordered Colonel James B. Swain of the 11th Regiment New York Volunteer Cavalry ("Scott's 900"),[2] which was part of the XXII Corps of the Union Army stationed in the Washington, D.C. defenses, to send a squad of troops to scout in the vicinity of Centreville, Virginia and to guard any remaining army supplies at Fairfax Court House.[61][62][63] Swain sent the regiment's B and C companies, 82 enlisted men and Captain Alexander G. Campbell, First Lieutenant Albert B. Holmes, Second Lieutenant Augustus B. Hazelton, and First Lieutenant George A. Dagwell, under the command of Major Seth Pierre Remington, on the mission.[1][62][64] The detachment left the same afternoon and by 10:00 p.m., the troops were camped at Fairfax Court House which the Union Army had left the day before.[62] Fires of coffee and bacon from the Union Army depot were burning when the squad arrived and the men saw what they decided must be local citizens examining the area and scavenging during the night.[62]

The fighting begins

Early on June 27, 1863, the New York troops left for Centreville.[64][65] They watered their horses at a small stream crossing the road just outside Fairfax Court House,[66] which would be the scene of some action when they returned.[65] Upon their arrival at Centreville, about 10:00 a.m., they found some Union Army hospital supplies which they inventoried and put in the care of a local storekeeper.[65] The soldiers thought they had seen mounted men in the woods in the direction of Fairfax Station.[65][67][68]

When they started their return trip, the cavalrymen came under fire from the woods about three miles from Fairfax Court House.[65] Major Remington sent two squads of four dismounted men into the woods to investigate.[65] One of the men's horses bolted and started to run toward Fairfax Court House.[65] Lt. Dagwell pursued the runaway horse and met the advanced guard of four men of the detachment just outside their old camp where they found citizens loading wagons with everything of value that had not been removed or burned by the Union Army in their move north.[65] As Lt. Dagwell found the horse entering the courtyard of the courthouse, he saw that the yard was filled with what he estimated to be about 65 Confederate troops.[65][69] Believing the Confederates must be some of Major John S. Mosby's partisans, Dagwell turned his horse and fled as the Confederates fired at him.[65][69]

When Lt. Dagwell returned to the area of the stream crossing the road into town and the rest of the New York troops came up, they found Confederates were drawn up in line in the woods up a ravine across the stream outside of town.[70] Dagwell's company, under fire but with no one hit, charged the Confederates, sending them retreating down the road to Fairfax Station.[69][70] Dagwell, Holmes and a few troops pursued the last of the fleeing Confederates, killing one and capturing a few others.[71][72]

Pursuit toward Fairfax Station

About one-half mile east of Fairfax Station, Stuart's staff officers, Major Andrew Reid Venable, Major Henry B. McClellan and Captain John Esten Cooke along with a courier, were eating breakfast at the house of a blacksmith who was shoeing their horses.[73] They were disturbed by some of the 11th New York cavalrymen running by on the road.[73] Cooke did not immediately flee because he wanted to have his horses shoed but when a second group from the 11th New York Cavalry approached, Cooke barely escaped.[73]

Continuing his pursuit, Dagwell came to the crest of a hill near Fairfax Station where the road led down to Fairfax Station and where a few Union troops who had outpaced him had halted.[2] They saw what Dagwell estimated was "at least" 2,000 Confederate troops and an artillery battery.[2][4][69] The New Yorkers had come upon Stuart's force on their way north.[69] Dagwell then realized that the small force they had driven from Fairfax Court House was not a group of Mosby's men but the advance guard of at least an entire Confederate brigade.[74]

Dagwell sent a soldier with the freshest-looking horse back to tell Remington of the situation and that he and the eight men with him would return as soon as their horses could recover from their just completed pursuit.[2] Dagwell and his eight men had to rest their horses but Dagwell could see the Confederates mounting up only about six hundred yards from his small squad.[74]

Action near Fairfax Station

Before the Confederates could approach Dagwell and his men, Major Remington appeared with the rest of the detachment.[74] When informed of the situation, Remington did not try to flee but ordered his men in line at the crest of the hill where Dagwell had viewed the 2,000-man Confederate force.[2][4][69][74] Meanwhile, Stuart had heard about the encounter with his staff officers and ordered Brigadier General Wade Hampton III to bring up the lead regiment quickly to meet the threat.[75] The advance unit of the Confederates, the 1st North Carolina Cavalry, then came over the hill and moved to within 30 yards of the Union line but did not move further forward despite orders which Dagwell could hear.[76] When the Union troops did not surrender after about 15 seconds, the opposing forces began to shoot at each other.[77]

Major Remington then ordered his squad to charge the Confederate force, which Dagwell had just told him must be an entire brigade of Confederate cavalry and had correctly estimated as being a minimum of 2,000 men.[77][78][79][80] The advance Confederates broke into the woods and Dagwell followed, only to soon find that he was alone.[77] When he came out to the point the New Yorkers had formed their line, he found only five Union men but also saw several dead and wounded Confederates, including a dead Confederate major beside the road.[77] Major John H. Whitaker, commander of the 1st North Carolina Cavalry was killed during the action.[61][81] Sergeant Charles A. Hartwell stated that the New Yorkers killed 5 Confederates and took 14 prisoners in the initial action.[1] Hartwell soon found himself with about a dozen men, including Major Remington, cut off from the other Union troops.[1] Remington and a few others, including Sergeant H. O. Morris, in the face of overwhelming numbers, had retreated from the nearby hill to which Remington had moved most of the men after their initial charge.[82] When he saw the Union movement, Hampton thought they were trying to position themselves to attack the rear of his force and sent a squadron to outflank them, virtually surrounding the majority of the Union men.[83] Sergeant Morris shot a Confederate officer who assaulted Major Remington during the melee that ensued during the fight for escape of the New Yorkers not trapped on the hill.[84]

After desperate fighting with pistols and sabers, Remington determined the situation was hopeless and ordered the men with him to withdraw.[85] Remington, Captain Campbell and 9 men including Sergeant Hartwell escaped along the railroad to a road that led to Annandale, Virginia.[85] After a brief encounter with a squad of Confederate cavalry along the way, Remington and his party reached the Alexandria, Virginia and the Washington, D.C. defenses.[85][86]

Historian Robert F. O'Neill states that at least three of the Union troopers were killed, one mortally wounded, 14 wounded and captured, 19 captured and 4 seriously wounded and left at a nearby home.[81] The walking wounded and able-bodied were taken along by the Confederates as prisoners.[81][87][88][89][90]

Capture of Lt. Dagwell and men

Meanwhile, Lt. Dagwell soon determined that they were cut off from the main body of the detachment and had no choice but to retreat.[77] After withdrawing from the area of the fight, Dagwell and his small group headed for Fairfax Court House, picking up another 11th New York cavalryman and a few prisoners whom he had been left to guard.[91] After a brief fight, the Union troops scattered five or six Confederates who came upon them.[91] With about eight men and five prisoners, Dagwell headed out on the road to Washington.[91]

Arriving at Annandale, Dagwell was wounded in an unsuccessful effort to evade capture and he and as many as eighteen men, including some he had picked up along the way, were captured by men of Fitzhugh Lee's brigade which had been detached from Stuart's other two brigades to proceed up the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and capture supplies.[92][93] Lee's brigade also captured a sutler's wagon train and more prisoners at Annandale.[94]

Delay at Fairfax Court House; Stuart's report

Since Hooker's final headquarters before his departure from Virginia was at Fairfax Court House, Stuart's men found considerable amounts of supplies still intact there.[95] This allowed Stuart's men to profitably plunder the Union Army depot at Fairfax Court House, including two warehouses and a sutler's wagon, after the end of the engagement.[81][94][96] After his men had eaten and rested for one or two hours, Stuart got his men back on the move toward Dranesville, Virginia.[81][96]

Stuart sent a letter to General Lee about the action at Fairfax Court House and the direction of march of Hooker's army.[97] Although a copy of the letter reached the Confederate War Department at Richmond, the message never reached General Lee.[97] The fight at Fairfax Court House had delayed Stuart by almost an additional half a day.[98] Lt. Dagwell commented that the fight at Fairfax was another lesson to the Confederates from June 1863 that Union troops were ready to dispute with them.[91] He and Sergeant Morris commented on the delay caused to Stuart by the action and its effect on his late arrival at Gettysburg.[99]

Aftermath

Stuart's movement across the Potomac River

After resting for several hours at Fairfax Court House, Stuart moved on to Dranesville, Virginia, where Fitzhugh Lee's brigade rejoined him.[59][81][100] Stuart then decided to cross the Potomac River that night at Rowser's Ford.[59][81] Because of the higher than normal water level, the Confederate crossing was not completed until 3:00 a.m. on June 28.[59][101] From Union prisoners captured at the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal just north of the river, Stuart learned that Hooker had been at Poolesville, Maryland 15 miles (24 km) to the west on the previous day and that the Army of the Potomac was headed north toward Frederick, Maryland.[59][102] From this intelligence, Stuart realized he should attempt to join Ewell as soon as possible.[59][102] Stuart nonetheless delayed his ride to capture a Union Army wagon train near Rockville, Maryland and to take additional prisoners, including a few fugitives from the 11th New York Cavalry.[102][103] He proceeded another 10 miles (16 km) to Brookeville, Maryland that day.[104]

Parole of the Union prisoners

Stuart realized that the prisoners would further delay and burden his men on the move if he continue to take them along.[81][104][105] At Brookeville, on June 28, before the Confederates paroled the prisoners, Stuart interrogated one of the prisoners from the 11th New York Cavalry, asking how many men had made the charge.[82][98] He was truthfully told that it was a single squadron and was not part of Pleasonton's command.[82][98] Stuart reportedly responded: "And you charged my command with eighty-two men? Give me five hundred such men and I will charge through the Army of the Potomac with them."[106][107] Stuart also approached Lt. Dagwell during the interrogation in an effort to discover whether Captain Campbell, who reportedly had threatened to execute Confederate prisoners, was among the 11th New York Cavalry prisoners.[108] During the night of June 28 and into the early morning on June 29, Stuart's adjutant general and chief of staff, Major Henry B. McClellan and other staff officers spent time and energy paroling prisoners, including those from the 11th New York Cavalry.[81][104][105]

Stuart's movement to Gettysburg

On the evening of June 29, Stuart's advance party, the 4th Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, chased two companies of the 1st Delaware Cavalry Regiment a long distance down the road to Baltimore from Westminister, Maryland, losing two lieutenants in the process.[104] On June 30, the riders leading Stuart's column saw a large column of Union cavalry across their path.[109][110] Encumbered by the wagon train and some new prisoners, Stuart's vanguard clashed with Union cavalry under the command of Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick at the Battle of Hanover near Hanover, Pennsylvania.[111] When the engagement broke off, Stuart detoured five miles to the east through Jefferson, Pennsylvania and waited until nightfall to resume his ride in order to better protect the threat from Kilpatrick's force to his left flank, including the wagons.[112][113]

In the morning, Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee's brigade, while proceeding across the road between York and Gettysburg, discovered that Major General Jubal Early had marched west towards Gettysburg.[112] He sent a staff officer in that direction to locate Early.[112] The officer, Major Andrew R. Venable, found General Lee and Lieutenant General Ewell near Gettysburg.[112] Despite Lee's intelligence, Stuart did not try to follow Early's route but moved away from Gettysburg toward Carlisle, Pennsylvania in an effort to find supplies and part of the Confederate Army.[112] Instead, he found Carlisle in possession of Union militia supported by artillery and a cavalry force.[112] As Stuart began to attack the town, he received orders from General Lee, who learned Stuart's location through Venable, to take a position on the left flank of the Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg.[114] On July 2, his force rode to Gettysburg, arriving in the afternoon.[114][115]

Effect of the Battle at Fairfax on Stuart's ride; subsequent criticism

In the account published in Thomas West Smith's book in 1897, Lt. Dagwell noted that the fight at Fairfax prevented Stuart from crossing the Potomac on June 27, contributing to his delay in rejoining the Army of Northern Virginia before the Battle of Gettysburg.[91] Historian Eric Wittenberg has stated: "The brave, desperate and hopeless charge of the 11th New York Cavalry at Fairfax Court House hindered Stuart for half a day."[116] Because the Confederates were defeated at Gettysburg, they sought to explain the defeat based on their own failures and weaknesses.[114] Stuart received more criticism for his delay in rejoining the main body of the Confederate army than most other Confederate commanders for their failures.[114] The criticism came not just from civilians but from his army colleagues.[117] On the other hand, modern historians Wittenberg and Petruzzi, after examining Stuart's ride and how Robert E. Lee fought the Battle of Gettysburg, and admitting that any analysis based on Stuart's cavalry rejoining the Army of Northern Virginia earlier in the campaign was speculative, concluded that the Confederates would have lost the battle whether Stuart had shown up earlier or not.[118]

A Confederate officer later recounted: "I think that without exception the most gallant charge, and the most desperate resistance that we ever met from the Federal cavalry, was at Fairfax, June 1863, when Stuart made a raid around the Union Army just before the battle of Gettysburg."[84][119][120]

See also

- Battle of Fairfax Court House (June 1861), an earlier battle on the same site

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Hartwell, Charles A. Chapter VIII (part): The Fairfax Fight in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013. p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e f Dagwell, George A. Chapter VIII: The Fairfax Fight in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013. p. 80. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ Wittenberg, Eric J., and J. David Petruzzi. Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart's Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2006. ISBN 978-1-932714-20-3. pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b c Wittenberg, 2006, p. 300 shows that three days after the battle, Hampton's brigade had a roster of Hampton and 4 staff, 6 colonels and 165 officers and 1,823 in the 6 regiments or legions, for a total of 1,999 men.

- ^ O'Neill, Robert F. Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas to Gettysburg. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012. ISBN 978-07864-7085-3. p. 246.

- ^ Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5. p. 51.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 7.

- ^ Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123. p. 359.

- ^ Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 978-0-684-84944-7. p. 490.

- ^ McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7. p. 646.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c McPherson, 1988, p. 647.

- ^ Eicher, 2001, p. 490.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 7

- ^ Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 978-0-395-86761-7. p. 17.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, pp. 11–18.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 51.

- ^ Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-253-33738-2. p. 237.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, pp. 52, 54.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968 p. 53.

- ^ a b c Coddington, 1968, p. 54.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 55.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 491–492.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, pp. 56–58.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 58.

- ^ Woodworth, Steven E., and Kenneth J. Winkle. Oxford Atlas of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-522131-2. p. 179.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006. p. xviii.

- ^ Pleasonton also was surprised by finding Stuart's cavalry just across the Rappahannock River near Brandy Station rather than 10 miles (16 km) further west at Culpeper. Coddington, 1968, 1968, p. 63.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 69.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 73.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 70.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Coddington, 1968, p. 74.

- ^ a b Rafuse, Ethan S. Robert E. Lee and The Fall of the Confederacy, 1863-1865. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2008; Paperback edition, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7425-5126-8. p. 51.

- ^ Hampton's Brigade had 178 fit officers and 2,032 effective men when it rejoined Stuart's command after the Battle of Chancellorsville. Hartley, Chris J. Stuart's Tarheels: James B. Gordon and His North Carolina Cavalry in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7864-6364-0. p. 123. The brigade had 1,999 men at Union Mills, Maryland, three days after the battle. Wittenberg, 2006, pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b c d e f g Coddington, 1968, p. 79.

- ^ Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War's Pivotal Campaign, 9 June–14 July 1863. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8032-7941-4. p. 132.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. xvi.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 106.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 107.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, pp. xviii–xix.

- ^ McPherson, 1988, p. 649 stated that after the Battle of Brandy Station: "His ego bruised, Stuart hoped to regain glory by some spectacular achievement in the invasion."

- ^ a b Rhodes, Charles Dudley. History of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co., 1900. OCLC 5211713. Retrieved June 27, 2013. p. 53.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 150.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. xix.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 109.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 110.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 150 states that the only mention of rendezvous at York is in the post-war biography of Stuart by his adjutant general Major Henry B. McClellan. Wert, 2008, pp. 262–263 questions whether the dispatch from General Lee mentioning York which McClellan described in those memoirs ever existed since no one else ever saw it and Lee's papers did not contain a copy.

- ^ a b Coddington, 1968, p. 111.

- ^ Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8117-0898-2. p. 204.

- ^ a b c Coddington, 1968, p. 112.

- ^ Wert, Jeffry D. Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J.E.B. Stuart. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7432-7819-5. p. 264.

- ^ Longacre, 2002, p. 205 states that if Stuart had proceeded through Hopewell Gap as recommended by Mosby, he would not have encountered Hancock's corps.

- ^ Wert, 2008, p. 265.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e f Coddington, 1968, p. 113.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 10.

- ^ a b Longacre, 1986, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Dagwell, George A. Chapter VIII: The Fairfax Fight in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013. p. 76.

- ^ Phisterer, Frederick. New York in the War of the Rebellion. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, State Printers, 1912. OCLC 1359922. Retrieved June 27, 2013. p. 943.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Robert F. Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas to Gettysburg. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012. ISBN 978-07864-7085-3. p. 243.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dagwell, 1897, p. 77.

- ^ The action took place between Fairfax Court House and Fairfax Station, Virginia, which are about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) apart. Because the culmination of the fight was closer to Fairfax Station, some historians have called this action a Skirmish at Fairfax Station. O'Neill, Robert F. Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas to Gettysburg. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012. ISBN 978-07864-7085-3. p. 245.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 153 and other accounts state that Stuart had ridden ahead even of his escorts on the morning of June 27 to scout the depot at Fairfax Station. Upon nearly running into the detachment of the 11th New York Cavalry, Stuart turned and sped back to his men. Dagwell's detailed account, which is written from the perspective of his own experience, mentions spotting the riders in the woods on the return from Centreville but does not mention that the Union troops nearly came upon Stuart himself.

- ^ Dagwell, 1897, p. 84 refutes a later account by a former Confederate officer that the detachment from the 11th New York Cavalry were on their way to Centreville when the action occurred when in fact they were on their way back.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Neill, 2012, p. 244.

- ^ a b Dagwell, 1897, p. 78.

- ^ Dagwell, 1897, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Sergeant H. O. Morris, 1897, p. 89 stated that he took 20 men to see who the riders in the woods were but the force was too strong for them. Upon their return to the main formation, they ran into the Confederates drawn up on the road into Fairfax Court House.

- ^ a b c Wittenberg, 2006, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Dagwell, 1897, p. 81.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Dagwell, 1897, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c d e Dagwell, 1897, p. 82.

- ^ O'Neill, 2012. p. 245.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Hartwell, 1897, p. 85 stated that the troops still supposed they were fighting "Mosby's guerillas" and assumed Remington also thought this was the situation. Dagwell, 1897, p. 80 says essentially the same thing, despite having just clearly stated that he told Remington they were confronting an entire brigade of Confederate cavalry.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i O'Neill, 2012, p. 246.

- ^ a b c Morris, 1897, p. 89.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 15.

- ^ a b Wittenberg, p. 2006, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Hartwell, 1897, p. 86.

- ^ Modern accounts, Wittenberg, 2006, p. 16 and O'Neill, 2012, p. 246 state that Remington and 18 men escaped or made it back to the Washington, D.C. defenses.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 153 wrote that 26 of Remington's men quickly became casualties, mostly as prisoners, and that the other troopers scattered but does not give a total count.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 16 says of the 82 New Yorkers "none of them escaped." This would account for 82 of the New Yorkers which was the number of men, but including officers the detachment had 87 troops in total. Wittenberg's figure is a misreading of his source, Sergeant Charles A. Hartwell, 1897, p. 86 who stated 4 of the New Yorkers were killed, 21 seriously wounded, and 57 others who had their horses fall or shot from under them were taken prisoner, including officers. Hartwell had noted the 11 officers and men, including himself, who made it back to Alexandria. Also, Hartwell's wording shows he double counted the wounded prisoners and is reasonably clear on this point. Wittenberg himself contradicted these total casualty figures earlier on the same page when he stated that Remington and 18 men escaped and others straggled in for several days after the fight. Clearly, these included the later paroled prisoners.

- ^ Dagwell, 1897, p. 84 stated that 26 of 36 men of Company C were casualties, including prisoners, but acknowledged that he did not know the number of Company B casualties.

- ^ Morris, 1897, p. 89 stated that the New Yorkers had five killed and about 70 wounded and captured out of 87 men. O'Neill's numbers appear closest to Hartwell's figures and to the actual number of Union casualties.

- ^ a b c d e Dagwell, 1897, p. 83.

- ^ O'Neill, 2012, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Dagwell, George A. Chapter VIII (part): Three Days with Stuart's Cavalry in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013. pp. 90–99.

- ^ a b Wert, 2008, p. 269.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 19.

- ^ a b Longacre, 2002, p. 207.

- ^ a b Wittenberg, 2006, p. 20

- ^ a b c Wittenberg, 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Morris, 1897, p. 90.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Longacre, 1986, p. 155.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d Coddington, 1968, p. 199.

- ^ a b Longacre, 1986, p. 157.

- ^ Wittenberg. 2006. p. 17.

- ^ Morris, 1897, p. 89.

- ^ Dagwell, "Three Days with Stuart's Cavalry", 1897, p. 98.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 159.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 159 said that Stuart's force "was about to pay for the time lost at Fairfax Station, Rockville, and, especially, Westminster."

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d e f Coddington, 1968, p. 201.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d Coddington, 1968, p. 202.

- ^ Coddington, 1968, p. 207.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, p. 297.

- ^ Longacre, 1986, p. 202.

- ^ Wittenberg, 2006, pp. 292–298.

- ^ Dagwell, 1897. p. 84.

- ^ Fairfax Court House and its immediate vicinity would be the scene of several small battles or skirmishes and raids during the war. Other skirmishes or small battles at Fairfax Court House occurred on June 1, 1861 (a skirmish which was the first engagement between uniformed land forces of both sides), July 17, 1861, November 18, 1861, November 27, 1861, September 2, 1862, December 27, 1862, December 28, 1862, January 9, 1863, January 28, 1863, June 4, 1863, June 27, 1863, August 6, 1863, August 24, 1863. Mosby's Fairfax Court House Raid occurred March 9, 1863. Operations were conducted around Fairfax Court House on July 28–August 3, 1863. Expeditions were conducted from Fairfax Court House August 4, 1863 and December 26–27, 1864. Scouts were conducted from Fairfax Court House on December 24–25, 1861, May 27–29, 1863, February 6–7, 1865, February 15–16, 1865 and April 8–10, 1865. Several other skirmishes occurred in the vicinity of Fairfax Court House or at nearby Fairfax Station, Virginia. Dyer, Frederick H. A compendium of the War of the Rebellion. pp. 885–886. Des Moines, IA: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908. OCLC 181358316. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

References

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 978-0-684-84569-2.

- Dagwell, George A. Chapter VIII (part): The Fairfax Fight in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- Dagwell, George A. Chapter VIII (part): Three Days with Stuart's Cavalry in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- Dyer, Frederick H. A compendium of the War of the Rebellion. pp. 885–886. Des Moines, IA: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908. OCLC 181358316. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 978-0-684-84944-7.

- Hartley, Chris J. Stuart's Tarheels: James B. Gordon and His North Carolina Cavalry in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7864-6364-0.

- Hartwell, Charles A. Chapter VIII (part): The Fairfax Fight in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123.

- Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations during the Civil War's Pivotal Campaign, 9 June–14 July 1863. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8032-7941-4.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8117-0898-2.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- Morris, H. O. "Recollections of the Fairfax Fight" in Chapter VIII (part): The Fairfax Fight in Smith, Thomas West. The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: "Scott's 900" Eleventh New York Cavalry: From the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico, 1861–1865. Chicago: The Veterans Association of the Regiment, 1897. OCLC 550919. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- O'Neill, Robert F. Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas to Gettysburg. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012. ISBN 978-07864-7085-3.

- Phisterer, Frederick. New York in the War of the Rebellion. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, State Printers, 1912. OCLC 1359922. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Poland, Jr., Charles P. The Glories Of War: Small Battle And Early Heroes Of 1861. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4184-5973-4. p. 249. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- Rafuse, Ethan S. Robert E. Lee and The Fall of the Confederacy, 1863-1865. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2008; Paperback edition, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7425-5126-8.

- Rhodes, Charles Dudley. History of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co., 1900. OCLC 5211713. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 978-0-395-86761-7.

- Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-253-33738-2.

- Wert, Jeffry D. Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J.E.B. Stuart. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7432-7819-5.

- Wittenberg, Eric J., and J. David Petruzzi. Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart's Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2006. ISBN 978-1-932714-20-3.

- Woodworth, Steven E., and Kenneth J. Winkle. Oxford Atlas of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-522131-2.