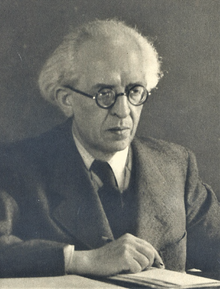

Vojtech Tuka

Vojtech Tuka | |

|---|---|

(1939) | |

| Prime Minister of Slovakia | |

| In office 26 October 1939 – 5 September 1944 | |

| President | Jozef Tiso |

| Preceded by | Jozef Tiso |

| Succeeded by | Štefan Tiso |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 26 October 1939 – 2 September 1944 | |

| Preceded by | Ferdinand Ďurčanský |

| Deputy, Czechoslovak Parliament | |

| In office 1925–1929 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 4, 1880 Hegybánya, Kingdom of Hungary (now Štiavnické Bane, Slovakia) |

| Died | August 20, 1946 (aged 66) Bratislava, Czechoslovakia (now Bratislava, Slovakia) |

| Nationality | Slovak |

| Political party | Slovak People's Party |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, professor, editor |

| Profession | Law |

Vojtech Lázar "Béla" Tuka (4 July 1880 – 20 August 1946) was a Slovak politician who served as Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the First Slovak Republic between 1939 and 1945. Tuka was one of the main forces behind the deportation of Slovak Jews to Nazi concentration camps in German occupied Poland. He was the leader of the radical wing of the Slovak People's Party.

Early career

Tuka, sometimes referred to by the Magyar name Béla, was born in Hegybánya, in the Hont County of the Kingdom of Hungary (today: Štiavnické Bane, Slovakia). He studied law at universities in Budapest, Berlin, and Paris. He became the youngest professor in the Kingdom of Hungary, teaching law in Pécs and—from 1914 to 1919—at the Elizabethan University in Bratislava. After the dissolution of that university in 1919, he worked as an editor in Bratislava.

After the founding of Czechoslovakia in late 1918, he joined the autonomist Slovak People's Party .Growing separatist sentiment would later enable Tuka's rise to power. In 1919, he was elected to the Presidium of the Countrywide Christian Socialist Party as nominee of the Slovak section.[citation needed] In 1923, he founded the organization Rodobrana ("Home Guard"), an armed militia. Tuka was also a deputy to the Czechoslovak parliament.

Espionage allegations and first jail sentence

On 1 January 1928, Tuka published an article titled "Vacuum iuris", alleging that there had been a suppressed annex to the 30 October 1918 "Martin Declaration" (the Slovak version of the Czechoslovak declaration of independence of 18 October 1918) by which Slovak representatives officially joined the newly founded state of Czechoslovakia. This annex, according to Tuka, stated that the declaration was, by agreement, to be valid for only ten years; after 30 October 1928, he claimed, Prague's writ would no longer run in Slovakia. The Prague government charged Tuka with espionage and high treason. Tuka was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment; he served about ten years of that sentence.[1][2]

The Slovak Republic and Tuka's rise to political power

On 9 March 1939, Czech troops moved into Slovakia in reaction to radical calls for independence from Slovak patriots (including Tuka, who had recently been released from prison). On 13 March, Adolf Hitler took advantage of this "Homolov Putsch", prompting Jozef Tiso—the Slovak ex–prime minister and Roman Catholic priest deposed by the Czech troops—to declare Slovak independence on 14 March by an act of the Slovak Assembly. The Czech part of Czechoslovakia was incorporated into the Third Reich as a protectorate. Tiso became Prime Minister of the new Slovak state on 14 March 1939; he was chosen as President on 26 October 1939 and immediately appointed Tuka as Prime Minister.[3]

The Salzburg Conference, concluded between Slovakia and the Reich in Salzburg, Austria on 28 July 1940, resulted in closer collaboration with Germany, and in Tuka and other political leaders increasing their powers at the expense of Tiso's original concept of a Catholic corporate state. Tuka attended the conference, as did Hitler, Tiso, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Alexander Mach (head of the Hlinka Guards), and Franz Karmasin, head of the local German minority. The agreement called for dual command by the Slovak People’s Party and the Hlinka Guard (HSĽS), and also an acceleration in Slovakia's anti-Jewish policies. The Reich appointed Stormtrooper leader Manfred von Killinger as the German representative in Slovakia. Tiso accepted these changes in subsequent conversation with Hitler.[4] As a result of the conference, two state agencies were created to deal with "Jewish affairs".[5][6]

Tuka and the persecution of Slovak Jews

On 3 September 1940, Tuka led the Slovak Assembly to enact Constitutional Law 210, a law authorizing the government to do everything necessary to exclude Jews from the economic and social life of the country.[7] Previous laws had already stripped them of political participation.[6] That November, on the 24th, Tuka and von Ribbentrop signed a protocol entering Slovakia into alliance with Germany, Japan, and Italy.[6] In 1940 Dieter Wisliceny, an SS Hauptsturmführer, was sent to Bratislava to act as an "adviser on Jewish affairs" to Tuka's government.[8] With Wisliceny, Tuka composed the Ordinance Judenkodex (Codex Judaicus, or Jewish Code) of 9 September 1941, which comprised 270 articles comprehensively denying rights to Slovak Jews.[7][8] The Code was longer than the Slovak Constitution.[8] It required that Jews wear the yellow star, annulled all debts owed to Jews, confiscated Jewish property, and expelled Jews from Bratislava, the Slovak capital.

Slovakia was the first state outside direct German control to agree to the deportation of its Jewish citizens.[9]

In 1942, Tuka strongly advocated the deportation of Slovakia's Jewish population to the eastern Nazi concentration camps. Together with Internal Affairs Minister Alexander Mach, Tuka, who was vice-chairman of the Slovak People's Party, encouraged ever-closer cooperation of the Party with Germany, supported by the Hlinka Guard, successor to the Rodobrana revived by Tuka. Twenty thousand Jews were to be deported under the German resettlement scheme, for which the Slovak government was to pay five hundred Reichsmark per deportee.[10] Tiso was perfectly aware of the deportations orchestrated by Tuka. In 1942 Tiso gave a speech in Holíč in which he justified ongoing deportations of Slovak Jews. Hitler commented after this speech "It is interesting how this little Catholic priest Tiso is sending us the Jews!".[11]

The deportation of Slovak Jews was halted in October 1942, at the order of the Slovak Council of Ministers.[12] A number of reasons for the sudden decision have been posited, including pressure from Slovak clergy.[10][13] A report by the Bratislava Sicherheitsdienst, the intelligence agency of the SS, stated that the reason for the sudden halt was a meeting called by Tuka on 11 August 1942. At that meeting, Tuka and the secretary-general of the Industrial Union told the ministers that Slovakia's economy could not withstand continued deportation of the Jews, causing the Council to order the halt.[12] Between 25 March and 20 October 1942, Slovakia sent about 57,700 Jews to Nazi concentration camps.[10] However, in September 1944, the deportation of Slovak Jews was resumed; by the end of the war in April 1945, about 13,500 additional Jews were deported.[10]

Fall from power and death

By 1943, Tuka's health had deteriorated to a point where his political activities were significantly diminished and at the beginning of 1944, he was planning his resignation. After large negotiations about his successor, he resigned on September 5, 1944, a few days after the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising. As he was prime minister at the time, the resignation involved the whole government. Tuka was replaced by Štefan Tiso (a distant relative of president Jozef Tiso). From then on, Tuka no longer took part in Slovak political life.

At the end of the war, having already suffered a stroke which confined him to a wheelchair, he emigrated together with his wife, nursing attendants and personal doctor to Austria, where he was arrested by Allied troops following the capitulation of Germany and handed over to the officials of the renewed Czechoslovakia. Following a brief trial, Vojtech Tuka was executed by hanging on August 20, 1946.

Swiss bank account

On 21 July 1997, after two years of lobbying, Slovak Jewish leaders persuaded the Czech cabinet to return property belonging to Slovak victims of the Holocaust.[14] That month, the Swiss Bankers Association published a list of World War II–era Swiss bank account holders with dormant accounts; the list included the name of Vojtech Tuka, according to Simon Wiesenthal, who urged that Tuka's account be turned over to the Swiss fund for victims of the Nazis.[15]

František Alexander, executive chairman of Slovakia's Central Association of Jewish Religious Communities, told The Slovak Spectator that the funds from the account should be allocated by an international council of justice. Jozef Weiss, head of the Association's office, said that the Association did not believe it had the legal or moral right to take money from Tuka's private account to repay a wrong done by the Slovak government. Instead, Weiss suggested, the money should be used to pay for the upkeep of the graves of Slovak soldiers who died in vain fighting alongside the Nazis against the Russian liberation forces on the Eastern Front.[14]

Ivan Kamenec, a Slovak historian of the war, said that Tuka's multiple posts "were all very well paid"; the offices of Foreign Minister and central committee member of HSĽS both paid over 10,000 Slovak crowns a month, he said. Although Kamenec refused to speculate on the size of Tuka's dormant account, he noted that Tuka's living requirements were modest.[14]

Notes

References

- Notes

- ^ Bartl (2002) p. 132.

- ^ Ward (2013) pp. 102-105.

- ^ Evans (2009) p. 395.

- ^ Ward (2013) pp. 211-213.

- ^ Birnbaum, Eli (2006). "Jewish History 1940–1949". The History of the Jewish People. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ a b c Bartl (2002) p. 142

- ^ a b Yahil (1991) pp. 179–181

- ^ a b c Dwork (2003) pp, 168–169

- ^ Hitler's Hangman. The Life of Heydrich. Robert Gerwarth, page 261)

- ^ a b c d Frucht (2005) p. 298

- ^ Ward (2013) p. 8 and pp. 234-7.

- ^ a b Aronson (2001)

- ^ Yahil (1991), p. 401

- ^ a b c Borský, Daniel (14 August 1997). "Jewish leaders decide not to pursue Tuka's Swiss stash". The Slovak Spectator. Bratislava, Slovakia: The Rock. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Jews angry Swiss bank list includes possible Nazis". Bangor Daily News. Vol. 109, no. 34. Bangor, Maine: Bangor Publishing. Associated Press. 25 July 1997. p. A6. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- Bibliography

- Aronson, Shlomo (2001). "Europa Plan". In Laqueur, Walter; Baumel, Judith Tydor (eds.). The Holocaust Encyclopedia. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08432-0.

- Bartl, Július (2002). Slovak History: chronology & lexicon. David Paul Daniel, trans. Wauconda, Ill.: Bolchazy-Carducci. ISBN 978-0-86516-444-4.

- Dwork, Debórah; Pelt, Robert Jan; Van Pelt, Robert Jan (2003). Holocaust: a history. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32524-9.

- Evans, Richard J. (2009). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Press.

- Frucht, Richard C., ed. (2005). Eastern Europe: an introduction to the people, lands, and culture. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- Ward, James Mace (2013). Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist Slovakia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4988-8.

- Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: the fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Ina Friedman and Haya Galai, trans. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-504523-9.

- V. Tuka Trial (in Slovak). B.m.: b. v., (1929). 1847 p. - available at ULB Digital Library

External links

- 1880 births

- 1946 deaths

- People from Banská Štiavnica District

- People from the Kingdom of Hungary

- Slovak People's Party politicians

- Slovak fascists

- Slovak collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Antisemitism in Slovakia

- Fascist rulers

- World War II political leaders

- Holocaust perpetrators in Slovakia

- Executed prime ministers

- Executed Slovak people

- Executed Czechoslovak collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Prime Ministers of Slovakia

- Independence activists