1990s in Japan

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

| This article is part of the series |

| Decades in Japan |

|---|

|

The 1990s in Japan was the beginning of economic turmoil and recession for that particular nation; resulting in their Lost Decade.[1] While the Lost Decade would finally end in 2000 for Japan,[1] this would become the era where young Japanese salarymen were forced to find different lines of work.

Technology

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

General trends

Technology began to outpace North American standards with Japanese vehicles often getting more miles per gallon than their North American rivals. People in Japan as well as the other oil-dependent nations of the world began to be dependent on high-speed rail networks (and other forms of mass transit like buses) as the price of gasoline began to skyrocket.[2] The average price of gasoline at the end of the next decade would rise to $8/gallon on a national level; making it unaffordable for most Japanese people to drive long distances unless necessary. Since gasoline prices have risen significantly since the 1990s worldwide, it will be inevitable for gasoline prices to go up to $20/gallon within the course of the 21st century.[3] After the 1990s ended and the 21st century began, Japanese residents (in addition to other people) will experience a return to local produce (through local farmers' markets instead of expensive grocery stores),[3] increased use of renewable energy like wind energy and solar energy,[3] the exodus from the exurbs to urban centers,[3] more electric car sales,[3] and a major shakeup of the airline industry.[3]

Video games

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

While new gaming consoles like the Super Famicom[4] and the Sony PlayStation[5] flooded the market, most young people began to move in with their parents, and read manga. This is because they could not acquire a job that would permit them to live independently and have all the amenities that they are accustomed to. Many video games were released during this decade (especially for the Super Famicom). Popular American titles like SimCity and SimEarth gained popularity for Japanese video gamers. The 1990s was also the era for Chrono Trigger,[6] Final Fantasy IV, Final Fantasy VI, and Final Fantasy VII. These games became multimillion-dollar blockbusters in Japan, Europe, and North America. However, the Famicom went into decline and most game companies halved their production of new 8-bit games by 1994.

Even the Nintendo Game Boy acquired popularity in Japan (spawning a lineup of Japan-exclusive video games)[7] and eventually the Japanese release of the Nintendo Game Boy Advance. Nintendo Power wrote an exposé about Japanese video games (using one of its first 50 issues). The exposé stated that Japanese video games were less censored than their North American counterparts. Video games that were released in Japan employed some form of sexual content,[8] brought forth the invocation of religious symbols,[8] utilized a level of violence never seen in North American games[8] (until the release of Doom in the mid-1990s), and mentioning tobacco in addition to alcohol so that the story could have more flavor.[8] These uncensored Japanese games even used vulgar language.

The Sega CD (known as the Sega Mega CD in Japan) first started to offer full motion video outside of the personal computer scene.[9] It became trendy in the 1990s (and in the 2000s) for players to create their own role-playing video games. Game creation software like RPG Tsukūru: Super Dante and RPG Tsukūru 2 made it possible for players to create role-playing games on their Super Famicom systems. While these games were not as graphically enhanced as Chrono Trigger or Final Fantasy VI which dominated this decade for role-playing video games, these "game creation tools" would allow the gamers of the 1990s to become the game designers of the 2000s and beyond. Sequels like RPG Maker 2000 and RPG Maker XP provided that the original two software in the series were highly successful.

Entertainment

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

Sports

Professional wrestling continued to decline well into the 1990s like it did in the 1980s.

Races often took place at either Suzuka Circuit or at Fuji Speedway. A NASCAR exhibition race was held in Motegi, Japan during the late 1990s in the hopes of getting people interested in stock car racing.[10]

During the 1990s, it became increasingly rare for Japanese businessmen to be able to play golf alongside their employers. Golf courses began closing up by the bundles and many young men (who would otherwise enter the workforce under a more ideal economy) began only to have golf experience from their years as a student. Besides the sporting aspect, golf was used in Japan in order to adapt to corporate culture.[11]

The 1990s was also the decade that the American film Mr. Baseball was released;[12] introducing an American audience to Japanese baseball. The Chunichi Dragons and the Yomiuri Giants became popular teams after the Mr. Baseball movie made mention of them. Nippon Professional Baseball was one of the sports to watch in Japan in addition to Formula One (featuring Japan's Satoru Nakajima who retired early in the 1990s but gained respect worldwide). The only perfect game of the 1990s for the Nippon Professional Baseball league came on May 18, 1994, with the Yomiuri Giants shutting out the Hiroshima Toyo Carp by a score of 6-0.

Television and movies

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

Anime like Dragon Ball Z (shōnen)[13] and Pokémon (shōnen) developed an international audience after being created in Japan. Girl-oriented (shōjo) anime like Sailor Moon also became of age during the 1990s. This show would be the inspiration for the 2000s anime Tokyo Mew Mew (known in North America as Mew Mew Power). J-Pop continued to be popular among Japanese female teenagers.

Social

Employment

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

While people were losing their jobs, technology still was advancing at an exponential rate—making more jobs obsolete as new technologies replaced the old. Manufacturing jobs were being replaced with service sector jobs just like they were doing in the Western countries—leading to people being underemployed in either minimum wage or near-minimum wage jobs. There was some economic recovery after this decade; but the spending on cars and whiskey had not returned to the levels that were reached during the Japanese economic boom of the 1980s. Japan made up for the labor shortages in the 1990s by hiring temporary workers without security or job benefits.

As of March 2010, the unemployment rate in Japan was 4.9%;[15] a very low number compared to the unemployment rate during the height of the Lost Decade.

Population decline

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (July 2013) |

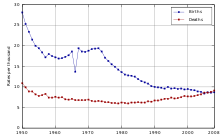

The 1990s would be the final decade where the birth rate in Japan would exceed the death rate. This is despite consistent attempts of government agencies throughout this decade to encourage procreation through targeted seductive advertising and media campaigns. However, the rest of the world's population will increase slowly until 2040 reaching 9 billion people.[16] The population of the world will eventually reach 9,202,458,484 people by the year 2050.[17] This would become the world's highest population ever in recorded history;[17]

It has been suggested that the population of Japan will fall from over 100 million in the 1990s to a mere 50 million by the year 2090. However, the most recent rise in the national birth rate of Japan happened on February 2007. Japan will see a 0.9% decline of their population after the year 2025—lowering their labor force while countries like Canada will see a rise in their labor force by that same year.[18]

Terrorism

The Tokyo subway sarin attack, usually referred to in the Japanese media as the Subway Sarin Incident (地下鉄サリン事件 Chikatetsu Sarin Jiken?), was an act of domestic terrorism perpetrated on March 20, 1995, in Tokyo, Japan by members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult.

In five coordinated attacks, the perpetrators released sarin on several lines of the Tokyo subway, killing 13 people, severely injuring 50 and causing temporary vision problems for nearly 1,000 others. The attack was directed against trains passing through Kasumigaseki and Nagatachō, home to the Japanese government. It was the most serious attack to occur in Japan since the end of World War II.

See also

References

- ^ a b http://fhayashi.fc2web.com/Prescott1/Postscript_2003/hayashi-prescott.pdf

- ^ Krauss, Clifford (May 10, 2008). "Gas Prices Send Surge of Riders to Mass Transit". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f When Gas Hits $20 Per Gallon

- ^ Kent, Steve L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokémon and Beyond : the Story Behind the Craze that Touched Our Lives and Changed the World. Prima. pp. 422–431. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

- ^ "Business Development/Japan". Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ^ "販売本数ランキング". ゲームランキング. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ^ "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. 2010-01-27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-14. Retrieved 2010-02-14.

- ^ a b c d "Nintendo Censorship Rules". Filibuster Cartoons. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ "[セガハード大百科] メガCD". 2004. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "Skinner wins NASCAR exhibition in Japan". Sunday Free Lance-Star. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ^ "Japan's Golf Course and the Environment". Archived from the original on 2010-06-06. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- ^ "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Mr. Baseball' a Culture-Clash Comedy". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ^ Clements, Jonathan; Helen McCarthy (September 1, 2001). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

- ^ Clyde Haberman (1987-01-15). "Japan's Zodiac: '66 was a very odd year". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

- ^ https://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20100301/ap_on_bi_ge/as_japan_economy Japan's Unemployment Rate - March 2010

- ^ World Population Clock — Worldometers

- ^ a b Data from U.S. Census Bureau, International Data Base Archived July 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Estimates updated December 2009. Retrieved on January 21, 2010

- ^ Paul S. Hewitt (2002). "Depopulation and Ageing in Europe and Japan: The Hazardous Transition to a Labor Shortage Economy". International Politics and Society. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.