East India Squadron

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

| East India Squadron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1835–1868 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Naval squadron |

The East India Squadron, or East Indies Squadron, was a squadron of American ships which existed in the nineteenth century, it focused on protecting American interests in the Far East while the Pacific Squadron concentrated on the western coasts of the Americas and in the South Pacific Ocean. Part of the duties of this squadron was serving with the Yangtze River Patrol in China. The East India Squadron was established in 1835 and existed until it became part of the Asiatic Squadron in 1868.

History

Shortly before Senator Levi Woodbury of New Hampshire became secretary of the Navy in 1831, Edmund Roberts had sent him a letter detailing the neglected state of Far Eastern commerce and whaling. Near the end of that year, American pepper trader Friendship returned to her home port of Salem, to report that Sumatran pirates had killed the first officer and two crewmen, and plundered the cargo. In response to public outcry, President Andrew Jackson dispatched the Potomac on the first of what were to be two punitive expeditions to Sumatra. The sloop-of-war Peacock was also dispatched, and, on the recommendation of Woodbury, carried Roberts as envoy to Cochin-China, Siam and Muscat, to negotiate treaties to place American commerce on a surer basis, and on an equality with that of the most favored nations.[1] Roberts succeeded with Siam and Muscat. Peacock returned in 1835–37 with Dr. W. S. W. Ruschenberger bearing ratifications of those treaties.[2] Peacock, which in 1828 had been broken down and rebuilt as an exploration vessel, joined the United States Exploring Expedition in 1838. East India Squadron Columbia and John Adams had also joined the circumnavigating Expedition, and, without having to detour, executed the Second Sumatran Expedition.

Formation

Except for whaling and pepper, U.S. trade with the Far East was limited, but for those who risked long voyage to trade fur, sandalwood, and cotton goods for Chinese silks and tea, the results were very profitable. Indeed, stories about the riches of Far East created the national myth about the vast potential of the China market. In an effort to turn the myth into reality, the US sent envoy Roberts to Cochin-China in 1835 aboard the Peacock, escorted by the schooner Enterprise under the command of Commodore Edmund P. Kennedy. They called first at the port of Canton, and Roberts' account gives a vivid description of the state of affairs there.[1]: pp. 63–74 Kennedy subsequently established the East India Squadron.[3]

First Opium War

Some Americans in China suffered during the first Opium War of 1839 as Chinese, indignant about British opium traders, failed to distinguish between English-speaking people of European ancestry. Commodore Kearny was given command of a squadron consisting of the 42-year-old frigate Constellation and the sloop Boston. Kearny arrived in China in March 1842 and the Opium War soon ended. Kearny first learned of the Treaty of Nanking when he arrived in Hong Kong. Kearny observed the treaty's provisions opening five Chinese ports to British trade, and sought equal trading opportunity for Americans. The Viceroy of Guangzhou offered Kearny a treaty giving Americans fair treatment. Kearny did not have authority to sign such a treaty, but tactfully informed Ke agreement would be forthcoming as soon as authorized negotiators arrived. Caleb Cushing reached China in 1844, and the Treaty of Wanghia was signed on 2 July.[4]

Opening of Japan

In December 1845, Commodore James Biddle exchanged ratifications of the Treaty of Wanghia[5] at Poon Tong (泮塘), a village outside Guangzhou. The treaty was the first treaty between China and the United States.

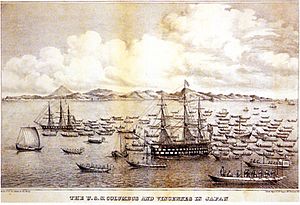

On July 20, 1846, he anchored with the two warships USS Columbus and USS Vincennes in Uraga Channel at the mouth to Edo Bay in an attempt to open up Japan to trade with the United States, but was ultimately unsuccessful. Biddle delivered his request that Japan agree to a similar treaty to that which he had just negotiated with China. Biddle eventually received the shogunate's response and was told that Japan forbade all commerce and communication with foreign nations besides that of the Dutch; also, he was informed that all foreign affairs were conducted through Nagasaki and that his ships should leave Uraga immediately.[6]

In 1852, Commodore Matthew C. Perry embarked from Norfolk, Virginia for Japan, in command of a squadron in search of a Japanese trade treaty. Aboard a black-hulled steam frigate, he ported Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and USS Susquehanna at Uraga Harbor near Edo (modern Tokyo) on July 8, 1853. His actions at this crucial juncture were informed by a careful study of Japan's previous contacts with Western ships and what could be known about the Japanese hierarchical culture. He was met by representatives of the Tokugawa Shogunate who told him to proceed to Nagasaki, where there was limited trade with the Netherlands and which was the only Japanese port open to foreigners at that time (see Sakoku).

Perry returned in February 1854 with twice as many ships, finding that the delegates had prepared a treaty embodying virtually all the demands in Fillmore's letter. Perry signed the Convention of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854 and departed, mistakenly believing the agreement had been made with imperial representatives.[7] The agreement was made with the Shogun, the de facto ruler of Japan.

Johanna Expedition

The Johanna Expedition was a naval operation that occurred in August 1851 during the American anti-slavery patrols in the Indian Ocean. It began in response the seizure of the merchant ship Maria and her captain, a man named Moores, in the small Sultanate of Johanna. The United States Navy sent the sloop-of-war USS Dale, under Captain William Pearson, to free Moores and to demand compensation for the incident. When the sultan refused, the Americans briefly bombarded a fort and blockhouse protecting the harbor of Matsamudu.[8][9]

Anti-piracy operations

In July 1855, Chinese pirates in the Hong Kong area captured four merchant ships, apparently of British subject. In response, on 4 August 1855, armed boats from the East India Squadron frigate USS Powhatan and the Royal Navy sloop-of-war HMS Rattler attacked the pirates at the Battle of Ty-ho Bay. HMS Eaglet towed the boats into position which then proceeded to destroy twenty of thirty-six junks. Seven merchant ships were also rescued. An estimated 500 pirates were killed or wounded and over 1,000 taken prisoner compared to an allied loss of nine dead and about a dozen wounded.

Second Opium War

The United States would see action again during the Second Opium War from 1856 to 1860. Four of the squadron's ships were involved in at least two battles. At the beginning of the war, the United States Navy frigate, USS San Jacinto and two sloops-of-war, USS Portsmouth and USS Levant, launched an attack against a series of Chinese forts along Pearl River. The engagement became known as the Battle of the Pearl River Forts and was fought in 1856. The second involvement of an East India Squadron ship was during the Second Battle of Taku Forts in 1859. The American warship, USS Powhatan, assisted an Anglo and French attack by bombarding the Taku Forts. No further engagements between Chinese and American forces during the war are known to have happened though American citizens living in Canton fought as militia at the 1856 battle at Canton.

Bombardment of Qui Nhon

On June 30, 1861, USS Saginaw, under James F. Schenck, silenced a fort at the entrance to Qui Nhon Bay, Cochinchina. This was after a Vietnamese artillery battery had fired upon her while she was searching for the missing boat and crew of an American merchant bark named Myrtle. After an engagement lasting just under an hour, the Chinese fort was destroyed and a large explosion was observed by the Americans. It became the only battle of the Cochinchina Campaign involving the United States which deployed the East India Squadron to protect American interests in the region.

Formosan Expedition

Following the Rover Incident of March 1867 in which the American bark Rover was wrecked and massacred by the Paiwan people of southern Formosa; the East India Squadron under Rear Admiral Henry H. Bell launched a punitive expedition in retaliation. On June 18, 1867, 181 officers, sailors and marines from two screw sloops-of-war landed with the intention of destroying the hostile threat. After six hours of marching through the hot tropical Formosan mountains and after several skirmishes, the Americans turned back to their ships. The expedition failed after the death of an American commander and the loss of several men due to the humid climate. They boarded USS Wyoming and USS Hartford and then set sail for Shanghai. A year later the squadron was merged into the new Asiatic Squadron.

Ships

USS Powhatan, under Commander William J. McCluney, was assigned to the East India Squadron and arrived on station via Cape of Good Hope 15 June 1853. Her arrival in Chinese waters coincided with an important phase of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s negotiations for commercial relations with the Japanese and the opening of two ports. She was Perry’s flagship during his November visit to Whampoa. On 14 February 1854 she entered Yedo Bay with the rest of the squadron and the Treaty of Kanagawa was signed on her deck on 31 March 1854.

Assigned to the East India Squadron under Commodore Matthew Perry, the USS Macedonian with Capt. Joel Abbot in command, was one of the six American ships arrayed off Uraga, Japan, 13 February 1854 during Perry's second visit to negotiate the opening of Japan to foreign trade.

After completing her trials, which she began in January 1851, the side-wheel steamer USS Susquehanna sailed on 8 June for the Far East to become flagship of the East India Squadron.

The USS Dolphin got underway 6 May 1848 to join the East India Squadron, protecting American citizens in Asiatic waters.

Recommissioned on 12 August 1850, USS Saratoga got underway on 15 September and proceeded to the western Pacific for service in the East India Squadron.

USS Levant sailed 13 November for Rio de Janeiro, the Cape of Good Hope, and Hong Kong, where she arrived to join the East India Squadron 12 May 1856. On 1 July she embarked the U.S. Commissioner to China for transportation to Shanghai, arriving 1 August.

Departing Norfolk 4 August, the USS Germantown sailed via the Cape of Good Hope to Ceylon, where on 22 December she joined Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall's East India Squadron off Point de Gala. For 2 years she cruised Far Eastern waters and visited the principal ports of China and Japan, where she found "uniform friendly reception" as the squadron guarded American interests in the Orient. Sailing via the Cape of Good Hope, she returned to Norfolk in April 1860

After a four-day stop at Singapore, where Commodore Armstrong relieved Commodore Joel Abbot in command of the East India Squadron, the frigate USS San Jacinto reached the bar off the mouth of the Me Nam (later the Chao Phraya) River.

The new side-wheel steamer USS Saginaw sailed from San Francisco Bay on 8 March 1860, headed for the western Pacific, and reached Shanghai, China, on 12 May. She then served in the East India Squadron, for the most part cruising along the Chinese coast to protect American citizens and to suppress pirates. She visited Japan in November but soon returned to Chinese waters. On 30 June 1861, she silenced a battery at the entrance to Qui Nhon Bay, Cochin China, which had fired upon her while she was searching for the missing boat and crew of American bark, Myrtle. On 3 January 1862, Saginaw was decommissioned at Hong Kong. On 3 July 1862, she returned to Mare Island for repairs.

Commanders

Successive Commanders-in-Chief of the East India Squadron were as follows.[10]

- Edmund P. Kennedy, 3 March 1835 – 10 October 1837

- George C. Read, 14 December 1837 – 13 June 1840

- Lawrence Kearny, 4 February 1841 – 27 February 1843

- Foxhall A. Parker, Sr., 27 February 1843 – 21 April 1845

- James Biddle, 21 April 1845 – 6 March 1848

- William Shubrick, 6 March 1848 – 13 May 1848

- David Geisinger, 13 May 1848 – 1 February 1850

- Philip Voorhees, 1 February 1850 – 30 January 1851

- John H. Aulick, 31 May 1851 – 20 November 1852

- Matthew C. Perry, 20 November 1852 – 6 September 1854

- Joel Abbot, 6 September 1854 – 15 October 1855

- James Armstrong, 15 October 1855 – 29 January 1858

- Josiah Tattnall, 29 January 1858 – 20 November 1859

- Cornelius Stribling, 20 November 1859 – 23 July 1861

- Frederick K. Engle, 23 July 1861 – 23 September 1862

- Cicero Price, 23 September 1862 – 11 August 1865

- Henry H. Bell, 11 August 1865 – 11 January 1868

Served in squadron

Also serving in the squadron at one time were:

- Thomas O. Selfridge

- John Pope

- Edward A. Terry served in the sloop Germantown, attached to the East India Squadron, from 1857 to 1859.

- William M. Wood served as fleet surgeon with the East India Squadron from 1856 to 1858

- Montgomery Sicard

- James Glynn

- Andrew Hull Foote commanded USS Portsmouth on 20–21 November 1856. Foote led a landing party that seized the barrier forts at Canton, China, in reprisal for attacks on American ships.

See also

References

- ^ a b Roberts, Edmund (1837) [First published in 1837]. "Introduction". Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat : in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock ... during the years 1832-3-4 (Digitized ed.). Harper & brothers. p. 5. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

I addressed a letter to the Hon. Levi Woodbury.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - ^ Stephen B. Young (2003). "Book review" (Journal of the Siam Society, Volume 91). Two Yankee Diplomats In 1830s Siam by Edmund Roberts and W. S. W. Ruschenberger. Edited with an introduction by Michael Smithies. Orchid Press. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

Also of some relevance for future Thai foreign policy are the various comments by Roberts and Ruschenberger as to how the Siamese seemed genuinely to like Americans and to prefer them over other Caucasian nations.

- ^ The Naval Institute historical atlas of the U.S. Navy By Craig L. Symonds, William J. Clipson, PG 64.

- ^ Hanks, Robert J., CAPT USN "Commodore Lawrence Kearny, the Diplomatic Seaman" United States Naval Institute Proceedings November 1970 pp.70–72

- ^ Sewall, John S. (1905). The Logbook of the Captain's Clerk: Adventures in the China Seas, p. xxxi.

- ^ Sewall, pp. xxxiv–xxxv, xlix, lvi.

- ^ Sewall, pp. 243–264.

- ^ "The Bombardment of Johanna". The New York Times. 4 February 1852.

- ^ http://www.history.navy.mil/special%20highlights/pirates/Suppression%20of%20Piracy%20on%20Johanna%20Island,%20August%201851,%20Amerman,%20USMC%20HD.pdf Archived 2011-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kemp Tolley, Yangtze Patrol: The U.S. Navy in China, pg 317

Further reading

- Long, David Foster (c. 1988). "Chapter Nine". Gold braid and foreign relations : diplomatic activities of U.S. naval officers, 1798–1883. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 207ff. ISBN 9780870212284. JSTOR 2163133. LCCN 87034879.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)