Roman Libya

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

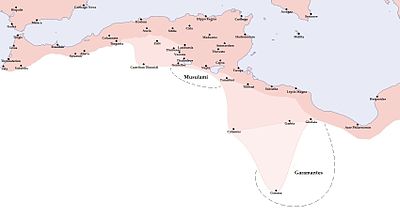

The area of North Africa which has been known as Libya since 1911 was under Roman domination between 146 BC and 672 AD. The Latin name Libya at the time referred to the continent of Africa in general.[1] What is now coastal Libya was known as Tripolitania and Pentapolis, divided between the Africa province in the west, and Creta et Cyrenaica in the east. In 296 AD, the Emperor Diocletian separated the administration of Crete from Cyrenaica and in the latter formed the new provinces of "Upper Libya" and "Lower Libya", using the term Libya as a political state for the first time in history.

History

After the final conquest and destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, northwestern Africa went under Roman rule and, shortly thereafter, the coastal area of what is now western Libya was established as a province under the name of Tripolitania with Leptis Magna capital and the major trading port in the region.

In 96 BC Rome peacefully obtained Cyrenaica (left as bequeathing by the king Ptolemy Apion) with the so-called sovereign Pentapolis, formed by the cities of Cyrene (near the modern village of Shahat), its port of Apollonia, Arsinoe (Tocra), Berenice (near modern Benghazi) and Barce (Marj), that will be transformed into a Roman province a couple of decades later in 74 BC. The Roman advance southward, however, was stopped by the Garamantes.

Cyrenaica had become part of the Roman Egypt already from the time of Ptolemy I Soter, despite frequent revolts and usurpations.[2]

In 74 BC was established the new province, governed by a legate of praetorian rank (Legatus pro praetor) and accompanied by a quaestor (quaestor pro praetor). But in 20 BC Cyrenaica was united to the island of Crete in the new province of Creta et Cyrenaica, because of the common Greek heritage.

The territory of Cyrenaica was characterized by the contrast between the coastal towns of the Pentapolis, inhabited by Greeks, and the territories inhabited by Libyans. The first had preserved their own institutions and were joined in an association, while their independence was recognized by the Ptolemaic Constitution of 248 BC. In some of these cities there was a huge minority of the population made of Hebrews, who were organized with their own rules. The few Roman citizens in the province were organized into the Conventus civium Romanorum.

The territory of Tripolitania was characterized by the presence of a strong punic influence in the three main cities (Tripolitania means "land of three cities") of Oea (actual Tripoli), Sabratha and Leptis Magna, but by the end of Augustus time the coastal area was nearly fully romanised.

Few were the raids of nomadic tribes of the desert against the cities of the province for at least the first two centuries. We know that at the time of Emperor Domitian, the Nasamones (a Libyan tribe living south of Leptis Magna) rebelled, bringing destruction and defeating the Legatus legionis of Augusta III Cneo Suelli Flacco, who had gone to meet them. But when he later returned with reinforcements, he crushed them all, so that Domitian could say before the Roman Senate the famous: "I prevented Nasamoni to exist".[3]

Instead more serious was the Jewish revolt striking mainly the Pentapolis in the time of Trajan (in 115-116 AD). In Cyrenaica, the rebels were led by one Lukuas or Andreas, who called himself "King" (according to Eusebius of Caesarea). His group destroyed many temples, including those to Hecate, Jupiter, Apollo, Artemis, and Isis, as well as the civil structures that were symbols of Rome, including the Caesareum, the basilica, and the thermae (Imperial public baths). The Greek and Roman populations were massacred: the 4th-century Christian historian Paulus Orosius records that the violence so depopulated the province of Cyrenaica that new colonies had to be established by Hadrian:

The Jews ... waged war on the inhabitants throughout Libya in the most savage fashion, and to such an extent was the country wasted that, its cultivators having been slain, its land would have remained utterly depopulated, had not the Emperor Hadrian gathered settlers from other places and sent them thither, for the inhabitants had been wiped out.[4]

After Hadrian Christianity started to be the most important religion in Roman Libya until the arrival of the Arabs.

During the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (born in Leptis Magna) there was sitting on the "Chair of Peter" Pope Victor I (181-191), also from Libyan Leptis Magna and probably its bishop.[5]

Until Victor's time, Rome celebrated the Mass in Greek: Pope Victor I changed the language to Latin, which was used in his native Roman Libya. According to Jerome, he was the first Christian author to write about theology in Latin.[6]

Furthermore, Arius, creator around 310 AD of the heresy Arianism, came from Ptolemais. Some centuries later in Cyrenaica, Monophysite adherents of the Coptic Church welcomed the Muslim Arabs as liberators from Byzantine oppression.[7]

Septimius Severus

The best period of Roman Libya was under emperor Septimius Severus, born in Leptis Magna. He favored his hometown above all other provincial cities, and the buildings and wealth he lavished on it made Leptis Magna the third-most important city in Africa, rivaling Carthage and Alexandria. In 205, he and the imperial family visited the city and received great honors. Among the changes that Severus introduced to this city were to create a magnificent new forum and to rebuild the docks.

He enriched all Libya, but mainly Tripolitania, defending it with an enlarged Limes Tripolitanus against the Garamantes: this powerful tribe was a client state of the Roman Empire, but as nomads they always endangered the fertile area of coastal Tripolitania.[8] Indeed, the limes was expanded under emperors Hadrian and Septimius Severus, in particular under the legatus Quintus Anicius Faustus in 197-201 AD.

Anicius Faustus was appointed legatus of the Legio III Augusta and built several defensive forts of the Limes Tripolitanus in Tripolitania, among which Garbia [9] and Golaia (actual Bu Ngem)[10] in order to protect the province from the raids of nomadic tribes. He fulfilled his task quickly and successfully.

As a consequence the Roman city of Ghirza, situated away from the coast and south of Leptis Magna, developed quickly in a rich agricultural area.[11] Ghirza became a "boom town" after 200 AD, when Septimius Severus had better organized the Limes Tripolitanus.

In late 202 Severus launched a campaign in the province of Africa. The legate of Legio III Augusta Anicius Faustus had been fighting against the Garamantes along the Limes Tripolitanus for five years, capturing several settlements from the enemy such as Cydamus, Gholaia, Garbia, and their capital Garama - over 600 km south of Lepcis Magna.[12]

By 203 the entire southern frontier of Roman Africa had been dramatically expanded and re-fortified. Desert nomads could no longer safely raid the region's interior and escape back into the Sahara. For another century the legacy of Septimius Severus gave peace and prosperity to Roman Libya.

Economy

As a Roman province, Libya was prosperous, and reached a golden age in the 2nd century AD, when the city of Leptis Magna rivalled Carthage and Alexandria in prominence.

For more than 400 years, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were wealthy Roman provinces and part of a cosmopolitan state whose citizens shared a common language, legal system, and Roman identity.

Roman ruins, like those of Leptis Magna and Sabratha in present-day Libya, attest to the vitality of the region, where populous cities and even smaller towns enjoyed the amenities of urban life - the forum, markets, public entertainments, and baths - found in every corner of the Roman Empire.[13]

Merchants and artisans from many parts of the Roman world established themselves in coastal Libya. Former soldiers were settled in the "Centenaria" area of Tripolitania, and the arid land was developed.[14] Dams and cisterns were built in the Wadi Ghirza (then not dry like today) to regulate the flash floods. These structures are still visible[15] As a consequence the area south of Leptis Magna became an important exporter of olive oil and cereals to Rome and the province was greatly "romanized", according to Theodore Mommsen.

The level of this romanization can be deducted even from the survival of the African Romance: the 12th-century Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi wrote that the people of the area of Gafsa (the Roman "Capsa", near northwestern Tripolitania) used a language that he called al-latini al-afriqi ("the Latin of Africa").[16]

Tripolitania was a major exporter of agricultural products, as well as a centre for the gold and slaves conveyed to the coast by the Garamentes, while Cyrenaica remained an important source of wines, drugs, and horses.[17]

Last centuries

After Septimius Severus Roman Libya slowly declined for the next century of so, before being destroyed by the tsunami of 365 AD. A recovery faltered, and well before the Arab invasion in the mid-7th century, Greco-Roman civilization had been collapsing in the area except Oea.

As part of his reorganization of the empire in 296 AD, the Emperor Diocletian separated the administration of Crete from Cyrenaica and in the latter formed the new provinces of "Upper Libya" and "Lower Libya", using the term Libya for the first time in history as an administrative designation. Indeed, the Tetrarchy reforms of Diocletian changed the administrative structure:

- Cyrenaica was split into two provinces: "Libya Superior" or "Libia Pentapolis", that comprised the above-mentioned Pentapolis with Cyrene as capital, and "Libya Inferior" or "Libia sicca", the Marmarica with the only significant city Paraetonium, each under a governor of the modest rank of praeses. Both belonged to the Diocese of Egypt, within the Praetorian prefecture of Oriens.

- Tripolitania, the largest split-off from Africa proconsularis, became part of the Diocese of Africa, subordinate to the prefecture of Italia et Africa. After the devastating tsunami of 365, the capital of Cyrenaica was moved to Ptolemais. With the definitive partition of the Roman empire in 395 AD, Tripolitania was attached to the Western Roman empire, while Cyrenaica to the eastern empire, later called Byzantine. It was briefly part of the Vandal Kingdom to the west, until its reconquest by Belisarius in 533 AD.

In April 534 AD, the former Roman provincial system along with the full apparatus of Roman administration was restored, under a praetorian prefect.[18] During the following years, under the smart general Solomon, who combined the offices of both magister militum and praetorian prefect of Africa, Roman rule in Libya was strengthened (Theodorias was refounded [19]), but the fighting continued against the Berber tribes on the hinterland.[20]

Solomon achieved significant successes against them, but his work was interrupted by a widespread military mutiny in 536. The mutiny was eventually subdued by Germanus, a cousin of Justinian, and Solomon returned in 539. He fell, however, in the Battle of Cillium in 544 against the united berber tribes, and Roman Libya was again in jeopardy. It would not be until 548 AD that the resistance of the Berber tribes would be finally broken by the talented general John Troglita. The last Latin epic poem of Antiquity, the de Bellis Libycis of Flavius Cresconius Corippus was written about this struggle.

Successively the province entered an era of relative stability and prosperity, and was organized as a separate exarchate in 584 AD. Eventually, under Heraclius, Libia and Africa would come to the rescue of the Empire itself, deposing the tyrant Phocas and beating back the Sassanids and the Avars.

But that was the last Roman achievement: in 642 AD Moslem Arabs started to conquer Libya. The Arabs succeeded in temporarily driving the Byzantines out of Tripoli in 645 AD, but they did not follow that conquest with the establishment of a permanent Arab presence in the city. No further raids were conducted until 661, when the new Umayyad dynasty under Mu'awiya ushered in a new era of Muslim expansion. An official campaign to conquer North Africa began in 663, and the Arabs soon controlled most major cities in Libya. Tripoli fell again in 666 AD, and this time the Muslims ensured their control of their new lands by not immediately retreating to Egypt after the conquest.

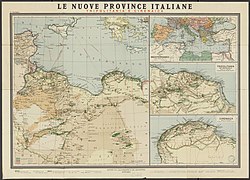

In 670 AD all Libya was in the hands of the Arabs: Roman rule since BCE 2nd century finally ended. Only in Benito Mussolini's time, more than one thousand years later, Libya was recreated as a political entity in 1934 (with a name borrowed from the Diocletian reforms).

Main cities

Life in Roman Libya was concentrated around a few coastal cities, mostly founded by Greeks and Phoenicians:

- Leptis Magna in Tripolitania [21][22]

- Oea in Tripolitania [23]

- Sabratha in Tripolitania [24][25]

- Cyrene (Pentapolis) [26]

- Apollonia (Pentapolis) [27]

- Arsinoe (Pentapolis) [28]

- Berenice (Pentapolis) [29]

- Barce (Pentapolis)[30]

- Ptolemais in Cyrenaica [31][32]

- Paraetonium in Marmarica

- Antipyrgon in Marmarica [33]

- Ghirza in Tripolitanian Sahara [34][35]

See also

- History of Libya

- Ancient Libya

- Tripolitania

- Cyrenaica

- Septimius Severus

- Pope Victor I

- Limes Tripolitanus

- Leptis Magna

- Sabratha

- African Romance

- Roman North Africa

- Ghirza

- Theodorias

- Libycus Nomos

Notes

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary

- ^ Ptolemy VIII, as a measure of preventive defense, made his will in favor of Rome if he died without legitimate heirs

- ^ Cassius Dio Cocceio,Roman History, LXVII, 4, 6.

- ^ Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, 7.12.6.

- ^ "History of the Catholic Church in Libya". Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ^ Kung, Hans. The Catholic Church: A Short History. New York; The Modern Library, 2003, p.44

- ^ Monophysites and arab conquest of Libya

- ^ Map of Limes tripolitanus

- ^ Gheriat el-Garbia

- ^ J.S. Wacher, The Roman world, Volume 1, Taylor & Francis, 2002, ISBN 0-415-26315-8, pp. 252-3

- ^ Roman city of Ghirza

- ^ Birley (2000), p. 153

- ^ Graham, Alexander (1902) Roman Africa: an outline of the history of the Roman occupation of North Africa, based chiefly upon inscriptions and monumental remains in that country Longmans, Green, and Co., London, Google Book, OCLC 2735641

- ^ Map of the agricultural "Centenaria" area

- ^ Ghirza

- ^ Capsa (in Italian)

- ^ Mommsen, Theodore. The Provinces of the Roman Empire Chapter: Africa

- ^ Codex Iustinianus, Book I, XXVII

- ^ Theodoria (Qasr Libya)

- ^ J.Bury: The reconquest of Africa

- ^ Images of Leptis Magna

- ^ Video of Leptis Magna

- ^ Oea images

- ^ Sabratha images

- ^ Video of Sabratha

- ^ Video of Cyrene

- ^ Apollonia images

- ^ Arsinoe images

- ^ Berenice/Euesperides

- ^ Tomb of Menecrate in Barce (in Italian)

- ^ Photos of Ptolemais

- ^ Video of Ptolemais & Apollonia

- ^ Antipyrgon

- ^ Ghirza (in french)

- ^ Ruins of Ghirza

Bibliography

- Lidiano Bacchielli, La Tripolitania, in "Storia Einaudi dei Greci e dei Romani", Geografia del mondo tardo-antico, vol.20, Milano, Einaudi, 2008.

- Barker, Graeme. Cyrenaica in Antiquity (Society for Libyan Studies Occasional Papers). Joyce Reynolds ISBN 0-86054-303-X

- J.R.González, Historia de las legiones Romanas, Madrid 2003.

- Graham, Alexander. Roman Africa: an outline of the history of the Roman occupation of North Africa, based chiefly upon inscriptions and monumental remains in that country. Publisher Longmans & Green (1902). University of California, 2007

- M.Grant, The Antonines: the Roman empire in transition, Londra e N.Y. 1994. ISBN 978-0-415-13814-7

- A.H.M.Jones, The later Roman empire 284-602, Baltymore 1986.

- Lennox Manton, Roman North Africa, 1988

- S.Rinaldi Tufi, Archeologia delle province romane, Roma 2007.

- G.Webster, The roman imperial army of the first and second century A.D., Oklahoma 1998.