Happily Ever After (1989 film)

| Happily Ever After | |

|---|---|

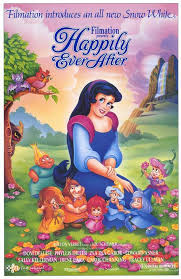

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | John Howley |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Lou Scheimer |

| Starring | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Frank Becker |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 1st National Film Corp. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3.3 million[1] |

Happily Ever After (also known as Snow White: Happily Ever After and Happily Ever After: Snow White's Greatest Adventure) is a 1990 American animated musical fantasy film written by Robby London and Martha Moran, directed by John Howley, and starring Irene Cara, Malcolm McDowell, Edward Asner, Carol Channing, Dom DeLuise and Phyllis Diller.[2]

Its story is a continuation of the fairy tale "Snow White", wherein the titular heroine and the Prince are about to be married, but a new threat appears in the form of the late evil Queen's vengeful brother Lord Maliss. The film replaces the Dwarfs with their female cousins, called the Dwarfelles, who aid Snow White against Maliss.

Happily Ever After is unrelated to Filmation's fellow A Snow White Christmas, a television animated film that was the company's earlier Snow White sequel. It was troubled by severe legal problems with The Walt Disney Company, and had a poor financial and critical reception following its wide release in 1993. A video game adaptation was released in 1994.

Plot

The film starts as the Looking Glass recaps the story of "Snow White". The cruel Queen is gone forever and the kingdom is now at peace as Snow White and the Prince prepare to marry.

Meanwhile, back at the castle of the Queen, her animal minions celebrate their freedom by throwing a party for themselves. The Queen's equally evil wizard brother, Lord Maliss, arrives at the castle, looking for his sister. After learning about the Queen's recent demise, he vows to avenge her death by any means. He transforms into a wyvern and takes control of the castle, transforming the area surrounding the castle into a perilous wasteland. Afterwards, Scowl the owl starts training his companion, a purple bat named Batso, on how to be evil.

The next day, Snow White and the Prince are in the meadow picking flowers for their wedding, when suddenly Lord Maliss, in his dragon form, begins attacking Snow White and the Prince as they are traveling to the cottage of the Seven Dwarfs. He takes away the Prince, who tried to fight him, but Snow White manages to flee into the woods.

Snow White reaches the cottage and meets the Dwarves' female cousins, the Seven "Dwarfelles": Muddy, Sunburn, Blossom, Marina, Critterina, Moonbeam, and Thunderella. The Dwarves have left the cottage after they bought another mine in a different kingdom, but the Dwarfelles gladly assist Snow White, taking her to visit Mother Nature at Rainbow Falls. Mother Nature has given the Dwarfelles individual powers to assist her; she holds Thunderella accountable for not being able to master her powers correctly, accuses the other Dwarfelles of improperly using their powers, and threatens to take them away as punishment. Lord Maliss attacks them, but Mother Nature shoots him with lightning, causing him to crash and return to his human form. Before leaving, Lord Maliss informs Snow White that the Prince is held captive in his castle.

Snow White and the Dwarfelles travel to Lord Maliss' castle in the Realm of Doom, along the way encountering a strange cloaked humanoid known as the Shadow Man. Lord Maliss sends his horned wolves after the group, and they manage to escape with the help of the Shadow Man. Lord Maliss is furious at this failure and transforms into his dragon form, finally capturing Snow White successfully himself and taking her to the castle. The Dwarfelles follow them and sneak into the castle as well while fending off Maliss's minions.

In the castle, Snow White is reunited with her Prince, who begins acting strangely, and takes her through a secret passage to supposedly escape. When Snow White realizes that he is not the real Prince but is actually Lord Maliss in disguise, he attempts to throw a magical red cloak on Snow White to petrify her into stone. He almost succeeds, but is attacked by the Shadow Man, whom he overpowers and seemingly kills. The Dwarfelles arrive and attack Lord Maliss as well, but fail and become petrified themselves. The only one unharmed is Thunderella, who finally gains control of her powers and assists Snow White to defeat Lord Maliss. The cloak is thrown on him and Lord Maliss is permanently petrified in mid-transition between his human and wyvern form.

As the sun shines onto the castle, the Dwarfelles are restored back to their normal selves. The Shadow Man wakes up and he turns out to be the Prince. The Prince reveals that Lord Maliss had cast a spell on him and he has been watching over Snow White during her journey, guarding her with his life. Mother Nature decides to let the Dwarfelles keep their powers because they have finally proven themselves by working together as one, and she allows them to attend Snow White's wedding.

In the end, Mother Nature takes in Batso and Scowl to be trained as her new apprentices. Snow White and the Prince are reunited, as the two of them share a kiss, and begin to live happily ever after.

Cast

- Irene Cara as Snow White: the beautiful young princess who is now engaged to the Prince.

- Malcolm McDowell as Lord Maliss: a terrible and powerful wizard seeking revenge for the death of his sister, the evil Queen.

- Phyllis Diller as Mother Nature: a ditsy embodiment of the forces of nature that gave the Seven Dwarfelles their powers.

- Michael Horton as the Prince: Snow White's handsome fiancé who has defeated the Queen and who is being kidnapped by Lord Maliss.

- Dom DeLuise as the Looking Glass: a smart-alec mirror who had served the evil Queen and now does the bidding of Lord Maliss and speaks in rhymes.

- Carol Channing as Muddy: a Dwarfelle who has power over the earth and the bossy leader of the Seven Dwarfelles.

- Zsa Zsa Gabor as Blossom: a Dwarfelle who has power over plants and flowers.

- Linda Gary as:

- Marina: a Dwarfelle who has power over all lakes and rivers.

- Critterina: a Dwarfelle who has power over animals.

- Jonathan Harris as the Sunflower: Mother Nature's rude assistant.

- Sally Kellerman as Sunburn: a Dwarfelle who has power over sunlight and a foul temper.

- Tracey Ullman as:

- Moonbeam: a Dwarfelle who has power over the night; according to Muddy, she is not herself during the daytime causing her to sleepwalk.

- Thunderella: a Dwarfelle who has power over the weather including thunder and lightning.

- Frank Welker as Batso the Bat: a timid bat who is Scowl's best friend.

- Welker also provides the uncredited vocal effects of Maliss' dragon form and one-horned wolves.

- Ed Asner as Scowl the Owl: a sarcastic owl who enjoys smoking and tries to impress Lord Maliss by capturing Snow White.

Songs

- "The Baddest" (music: Ashley Hall, lyrics: Stephanie Tyrell) - Ed Asner

- "Thunderella's Song" (music: Richard Kerr, lyrics: Stephanie Tyrell) - Tracey Ullman

- "Mother Nature's Song" (music: Barry Mann, lyrics: Stephanie Tyrell) - Phyllis Diller

- "Love is the Reason" (music and lyrics: John Lewis Parker) - Irene Cara

Production and release

The film began production in 1986,[3] done 60% overseas.[4] Filmation had previously developed a plan to create a series of direct-to-video sequels to popular Disney motion pictures, but only this film and Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night were ever completed. According to the producer Lou Scheimer, the black actress Irene Cara's casting as Snow White was regarded by many (including Cara herself) at the time as strangely "colorblind".[5] The Mother Nature's original casting actress was Joni Mitchell.[6] Scheimer also noted his version of the Snow White as the story's actual heroine as it is she who rescues the prince in an inversion of the traditional version.[7] Lord Maliss was based on Basil Rathbone.[8]

However, the Walt Disney Productions chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg and spokesman Tom Deegan regarded the projects as "blatant rip-offs" of their properties.[7][9] This led to a lawsuit by The Walt Disney Company in 1987 following the release of Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night,[7][10] Afterwards Filmation promised their characters would not resemble the ones from the Disney version[11] and changed the title of the film to Happily Ever After.[12] Working titles included Snow White in the Land of Doom, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfelles, and Snow White: The Adventure Continues.[5]

Happily Ever After was reportedly completed by 1988[13] and was supposed to be released in the United States in 1990; however, Filmation went out of business in 1989.[14] While the film did receive a 1990 theatrical release in France, it was not released to theaters in the United States until May 28, 1993,[15] during the same summer that Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was re-released theatrically.[16] However, it took only $1.76 million over the four-day Memorial Day weekend,[17] $2.8 million after ten days, and $3.2 million by the next month.[6] The release was preceded by a $10 million advertising campaign and a substantial merchandising effort from the North American distributor First National Film Corp;[7][7] First National's bankruptcy followed just weeks after the film's failed premiere[6] and its President, Milton Verret, was later charged with defrauding investors and found guilty.[18][19] Afterwards the film was released on VHS by Worldvision and later on DVD (in an edit censoring some violence) by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment.

As of 2019, the film is now owned by Universal Pictures through DreamWorks Animation under their ownership of DreamWorks Classics, which holds the rights to much of the Filmation catalog, including this film.

Reception

Despite a substantial advertising campaign and having been expected to become "one of the biggest hits of the year," Happily Ever After did poorly in the box office during its theatrical run.[11] Its domestic gross was only $3,299,382.[1]

Critics generally disliked the film. According to Stephen Holden of The New York Times, "visually, Happily Ever After is mundane. The animation is jumpy, the settings flat, the colors pretty but less than enchanting. The movie's strongest element is its storytelling, which is not only imaginative but also clear and smoothly paced."[20] Kevin Thomas of Los Angeles Times opined the characters (especially the Prince) were "bland" and called the film's songs "instantly forgettable."[21] Rita Kemple of The Washington Post derided the "inane" humor attempts as well as "badly drawn characters" and their "clumsy" animation.[22] Desert News' Chris Hicks similarly wrote, "Sadly, the animation here is weak, the gags even weaker and the story completely uninvolving."[23] Steve Daly of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a score of F and recommended to "give this Snow White the big kiss-off."[24] Chicago Tribune's Mark Caro wrote that the comparison with Disney's classic Snow White "couldn't be more brutal."[25] Currently the film has a 40% on Rotten Tomatoes.[26]

Some other reviews were more positive. Jeff Shannon of Seattle Times opined "this one's a cut above in the animation contest, deserving attention in the once-exclusive realm of Disney and Don Bluth. It almost, but not quite, escapes those nagging comparisons."[27] Ralph Novak of People wrote that although "the animation is less sophisticated than the Disney standard," the story "moves nicely, though," with a "colorful" cast of voices.[28] Candice Russell of Sun-Sentinel called it "a sweet and likable film," crediting a screenplay "that avoids cuteness and sentimentality and remembers that kiddie fare is fun" and "a few charming songs adding to the merriment."[29]

Video game

An unreleased Nintendo Entertainment System video game was planned in 1991.[30][31] A Sega game was also considered in 1993.[7] An eventual Super Nintendo Entertainment System version was developed by ASC Games and released by Imagitec Design four years later (and one year after the film's release) in 1994.

References

- ^ a b "Happily Ever After (1993)". Box Office Mojo. 1993-06-18. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 182. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ McCall, Douglas L. (2015). Film Cartoons: A Guide to 20th Century American Animated Features and Shorts. McFarland. ISBN 9781476609669.

- ^ "Production Is Less Animated at Filmation Studio". Los Angeles Times. 1988-01-01. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ a b Scheimer, Lou; Mangels, Andy (2012). Lou Scheimer: Creating the Filmation Generation. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490441.

- ^ a b c "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ a b c d e f "A Snow White For The '90s - Orlando Sentinel". Articles.orlandosentinel.com. 1993-05-27. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ "Happily Ever After". Variety. 1990-01-01. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean; Times, Special to The New York (1985-05-01). "Video Alters Economics of Movie Animation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ Walt Disney Productions v. Filmation Associates, vol. 628, February 20, 1986, p. 871, retrieved 2019-05-18

- ^ a b "Non-Disney 'Snow White' Sequel Has Unhappy Box-Office Opening". Apnewsarchive.com. 1993-06-01. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ SNOW WHITE REVISITED: THE QUEEN'S DEAD, BUT CONFLICT ISN'T BANISHED, Dayton Daily News, May 28, 1993.

- ^ "Someday the Film Will Come". Los Angeles Times. 1993-05-17. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "Group W sells Filmation." Broadcasting, February 13, 1989, pg. 94

- ^ "Snow White through the years - Timelines - Los Angeles Times". Timelines.latimes.com.s3-website-us-west-1.amazonaws.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Bates, James (1993-05-17). "Someday the Film Will Come". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ^ Snow White sequel opens on a sad note, Lodi News-Sentinel, June 2, 1993.

- ^ Norris, Floyd (1995-06-28). "S.E.C. Charges Distributor Defrauded Film's Investors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "SEC News Digest" (PDF). www.sec.gov. 1998-07-27.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (1993-05-29). "Review/Film; 56 Years Later, More of Snow White". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (1993-05-28). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Happily Ever After': Sadly Disappointing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- ^ Rita Kempley, Happily Ever After, The Washington Post, May 29, 1993

- ^ "Film review: Happily Ever After". DeseretNews.com. 1993-05-28. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ Steve Daly, Happily Ever After, Entertainment Weekly, Jun 04, 1993.

- ^ Mark Caro (1993-05-31). "Dwarfed By The Real Thing - Chicago Tribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Happily Ever After, retrieved 2019-01-12

- ^ Shannon, Jeff (1993-05-28). "Entertainment & the Arts | Snow White Cartoon Nice To Look At But Too Preachy | Seattle Times Newspaper". Community.seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Novak, Ralph. "Picks and Pans Review: Happily Ever After". People.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ CANDICE RUSSELL, Film Writer (1993-06-02). "Feature Takes Children Beyond Happy Ending Of `Snow White` - Sun Sentinel". Articles.sun-sentinel.com. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- ^ Happily Ever After (Unreleased), 1991, retrieved 2019-05-18

- ^ "Nintendo Player – A Not-For-Profit Classic Gaming Fansite - Happily Ever After (Unreleased, Nintendo Entertainment System)". www.nintendoplayer.com. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

External links

- 1990 films

- 1990 animated films

- 1990s American animated films

- 1990s fantasy adventure films

- American children's animated adventure films

- American children's animated fantasy films

- American fantasy adventure films

- Animated musical films

- English-language films

- Films about shapeshifting

- Filmation animated films

- Fictional owls

- Films about bats

- Films about royalty

- Films about witchcraft

- Films based on Snow White

- Films featuring anthropomorphic characters

- Unofficial sequel films