Bell X-1

| X-1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| X-1 #46-062, nicknamed Glamorous Glennis | |

| Role | Experimental rocket plane |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Bell Aircraft |

| First flight | 19 January 1946 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | United States Air Force National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics |

| Number built | 7 |

The Bell X-1 (Bell Model 44) is a rocket engine–powered aircraft, designated originally as the XS-1, and was a joint National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics–U.S. Army Air Forces–U.S. Air Force supersonic research project built by Bell Aircraft. Conceived during 1944 and designed and built in 1945, it achieved a speed of nearly 1,000 miles per hour (1,600 km/h; 870 kn) in 1948. A derivative of this same design, the Bell X-1A, having greater fuel capacity and hence longer rocket burning time, exceeded 1,600 miles per hour (2,600 km/h; 1,400 kn) in 1954.[1] The X-1, piloted by Chuck Yeager, was the first manned airplane to exceed the speed of sound in level flight and was the first of the X-planes, a series of American experimental rocket planes (and non-rocket planes) designed for testing new technologies.

Design and development

Parallel development

In 1942, the United Kingdom's Ministry of Aviation began a top secret project with Miles Aircraft to develop the world's first aircraft capable of breaking the sound barrier. The project resulted in the development of the prototype turbojet-powered Miles M.52, designed to reach 1,000 miles per hour (870 kn; 1,600 km/h) (over twice the existing airspeed record) in level flight, and to climb to an altitude of 36,000 ft (11 km) in 1 min and 30 sec.

By 1944, design of the M.52 was 90% complete and Miles was told to go ahead with the construction of three prototypes. Later that year, the Air Ministry signed an agreement with the United States to exchange high-speed research and data. Miles' Chief Aerodynamicist Dennis Bancroft stated that Bell Aircraft personnel visited Miles later in 1944, and were given access to the drawings and research on the M.52,[2] but the U.S. reneged on the agreement and no data was forthcoming in return.[3] Unknown to Miles, Bell had already started construction of a rocket-powered supersonic design of their own, with a conventional horizontal tail. Bell was battling the problem of pitch control due to "blanking" the elevators.[4][5] A variable-incidence tail appeared to be the most promising solution; and having already decided on it for the M.52, the Miles and RAE tests supported this.[6]

Research studies

The XS-1 was first discussed in December 1944. Early specifications for the aircraft were for a piloted supersonic vehicle that could fly at 800 miles per hour (1,300 km/h) at 35,000 feet (11,000 m) for two to five minutes.[7] On 16 March 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces Flight Test Division and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) contracted with the Bell Aircraft Company to build three XS-1 (for "Experimental, Supersonic", later X-1) aircraft to obtain flight data on conditions in the transonic speed range.[8]

The aircraft's designers built a rocket plane after considering alternatives. Turbojets could not achieve the required performance at high altitude. An aircraft with both turbojet and rocket engines would be too large and complex.[7] The X-1 was, in principle, a "bullet with wings", its shape closely resembling a Browning .50-caliber (12.7 mm) machine gun bullet, known to be stable in supersonic flight.[9] The shape was followed to the extent of seating its pilot behind a sloped, framed window inside a confined cockpit in the nose, with no ejection seat.

Swept wings were not used because too little was known about them. As the design might lead to a fighter the XS-1 was intended to take off from the ground, but the end of the war made the B-29 Superfortress available to carry it into the air.[7] After the rocket plane experienced compressibility problems during 1947, it was modified with a variable-incidence tailplane following technology transfer with the United Kingdom.[2]

Following conversion of the X-1's horizontal tail to all-moving (or "all-flying"), test pilot Chuck Yeager verified it experimentally, and all subsequent supersonic aircraft would either have an all-moving tailplane or be "tailless" delta winged types.[10]

The rocket engine was a four-chamber design built by Reaction Motors Inc., one of the first companies to build liquid-propellant rocket engines in the U.S. After considering hydrogen peroxide, acid and aniline, and nitromethane as fuels, the rocket burned ethyl alcohol diluted with water with a liquid oxygen oxidizer. Its four chambers could be individually turned on and off, so thrust could be changed in 1,500 lbf (6,700 N) increments. The fuel and oxygen tanks for the first two X-1 engines were pressurized with nitrogen, reducing flight time by about 1+1⁄2 minutes and increasing landing weight by 2,000 pounds (910 kg), but the rest used gas-driven turbopumps, increasing the chamber pressure and thrust while making the engine lighter.[11][7]

Operational history

Bell Aircraft chief test pilot Jack Woolams became the first person to fly the XS-1. He made a glide-flight over Pinecastle Army Airfield, in Florida, on 25 January 1946. Woolams completed nine more glide-flights over Pinecastle, with the B-29 dropping the aircraft at 29,000 feet (8,800 m) and the XS-1 landing 12 minutes later at about 110 miles per hour (180 km/h). In March 1946 the #1 rocket plane was returned to Bell Aircraft in Buffalo, New York for modifications to prepare for the powered flight tests. Four more glide tests occurred at Muroc Army Air Field near Palmdale, California, which had been flooded during the Florida tests, before the first powered test on 9 December 1946. Two chambers were ignited, but the aircraft accelerated so quickly that one chamber was turned off until reignition at 35,000 feet (11,000 m), reaching Mach 0.795. After the chambers were turned off the aircraft descended to 15,000 feet (4,600 m), where all four chambers were briefly tested.[7][12] After Woolams' death on 30 August 1946, Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin was the primary Bell Aircraft test pilot for the X-1-1 (serial 46-062). He made 26 successful flights in both X-1s from September 1946 through June 1947.

The Army Air Forces was unhappy with the cautious pace of flight envelope expansion and Bell Aircraft's flight test contract for airplane #46-062 was terminated. The test program was acquired by the Army Air Force Flight Test Division on 24 June after months of negotiation. Goodlin had demanded a US$150,000 bonus (equivalent to $2.05 million in 2023) for exceeding the speed of sound.[13]: 96 [14][15] Flight tests of the X-1-2 (serial 46-063) would be conducted by NACA to provide design data for later production high-performance aircraft.

Mach 1 flight

The first manned supersonic flight occurred on 14 October 1947, less than a month after the U.S. Air Force had been created as a separate service. Captain Charles "Chuck" Yeager piloted USAF aircraft #46-062, nicknamed Glamorous Glennis for his wife. The airplane was drop launched from the bomb bay of a B-29 and reached Mach 1.06 (700 miles per hour (1,100 km/h; 610 kn)).[1] Following burnout of the engine, the plane glided to a landing on the dry lake bed.[13]: 129–130 This was XS-1 flight number 50.

The three main participants in the X-1 program won the National Aeronautics Association Collier Trophy in 1948 for their efforts. Honored at the White House by President Truman were Larry Bell for Bell Aircraft, Captain Yeager for piloting the flights, and John Stack for the contributions of the NACA.

The story of Yeager's 14 October flight was leaked to a reporter from the magazine Aviation Week, and The Los Angeles Times featured the story as headline news in their 22 December issue. The magazine story was released on 20 December. The Air Force threatened legal action against the journalists who revealed the story, but none ever occurred.[16] The news of a straight-wing supersonic aircraft surprised many American experts, who like their German counterparts during the war believed that a swept-wing design was necessary to break the sound barrier.[7] On 10 June 1948, Air Force Secretary Stuart Symington announced that the sound barrier had been repeatedly broken by two experimental airplanes.[17][18]

On 5 January 1949, Yeager used Aircraft #46-062 to perform the only conventional (runway) launch of the X-1 program, attaining 23,000 ft (7,000 m) in 90 seconds.[19]

Legacy

The research techniques used for the X-1 program became the pattern for all subsequent X-craft projects. The X-1 project assisted the postwar cooperative union between U.S. military needs, industrial capabilities, and research facilities. The flight data collected by the NACA from the X-1 tests then proved invaluable to further US fighter design throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

In 1997, the United States Postal Service issued a fiftieth anniversary commemorative stamp recognizing the Bell X1-6062 aircraft as the first aeronautical vehicle to fly at supersonic speed of approximately Mach 1.06 (1,299 km/h; 806.9 mph).

Variants

Later variants of the X-1 were built to test different aspects of supersonic flight; one of these, the X-1A, with Yeager at the controls, inadvertently demonstrated a very dangerous characteristic of fast (Mach 2 plus) supersonic flight: inertia coupling. Only Yeager's skills as an aviator prevented disaster; later Mel Apt would lose his life testing the Bell X-2 under similar circumstances.

X-1A

(Bell Model 58A)

Ordered by the Air Force on 2 April 1948, the X-1A (serial number 48-1384) was intended to investigate aerodynamic phenomena at speeds greater than Mach 2 (681 m/s, 2,451 km/h) and altitudes greater than 90,000 ft (27 km), specifically emphasizing dynamic stability and air loads. Longer and heavier than the original X-1, with a stepped canopy for better vision, the X-1A was powered by the same Reaction Motors XLR-11 rocket engine. The aircraft first flew, unpowered, on 14 February 1953 at Edwards AFB, with the first powered flight on 21 February. Both flights were piloted by Bell test pilot Jean "Skip" Ziegler.

After NACA started its high-speed testing with the Douglas Skyrocket, culminating in Scott Crossfield achieving Mach 2.005 on 20 November 1953, the Air Force started a series of tests with the X-1A, which the test pilot of the series, Chuck Yeager, named "Operation NACA Weep". These culminated on 12 December 1953, when Yeager achieved an altitude of 74,700 feet (22,800 m) and a new airspeed record of Mach 2.44 (equal to 1620 mph, 724.5 m/s, 2608 km/h at that altitude). Unlike Crossfield in the Skyrocket, Yeager achieved that in level flight. Soon afterwards, the aircraft spun out of control, due to the then not yet understood phenomenon of inertia coupling. The X-1A dropped from maximum altitude to 25,000 feet (7,600 m), exposing the pilot to accelerations of as much as 8g, during which Yeager broke the canopy with his helmet before regaining control.[20]

On 28 May 1954, Maj. Arthur W. Murray piloted the X-1A to a new record of 90,440 feet (27,570 m).[21]

The aircraft was transferred to NACA during September 1954, and subsequently modified. The X-1A was lost on 8 August 1955, when, while being prepared for launch from the RB-50 mothership, an explosion ruptured the plane's liquid oxygen tank. With the help of crewmembers on the RB-50, test pilot Joseph A. Walker successfully extricated himself from the plane, which was then jettisoned. Exploding on impact with the desert floor, the X-1A became the first of many early X-planes that would be lost to explosions.[22][23]

X-1B

(Bell Model 58B)

The X-1B (serial 48-1385) was equipped with aerodynamic heating instrumentation for thermal research (more than 300 thermal probes were installed on its surface). It was similar to the X-1A except for having a slightly different wing. The X-1B was used for high-speed research by the U.S. Air Force starting from October 1954, prior to being transferred to the NACA during January 1955. NACA continued to fly the aircraft until January 1958, when cracks in the fuel tanks forced its grounding. The X-1B completed a total of 27 flights. A notable achievement was the installation of a system of small reaction rockets used for directional control, making the X-1B the first aircraft to fly with this sophisticated control system, later used in the North American X-15. The X-1B is now at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base at Dayton, Ohio, where it is displayed in the Museum's Maj. Gen. Albert Boyd and Maj. Gen. Fred Ascani Research and Development Gallery.

X-1C

(Bell Model 58C) The X-1C (serial 48-1387)[24] was intended to test armaments and munitions in the high transonic and supersonic flight regimes. It was canceled while still in the mockup stage, as the development of transonic and supersonic-capable aircraft like the North American F-86 Sabre and the North American F-100 Super Sabre eliminated the need for a dedicated experimental test vehicle.[25]

X-1D

(Bell Model 58D) The X-1D (serial 48-1386) was the first of the second generation of supersonic rocket planes. Flown from an EB-50A (s/n #46-006), it was to be used for heat transfer research. The X-1D was equipped with a new low-pressure fuel system and a slightly increased fuel capacity. There were also some minor changes of the avionics suite.

On 24 July 1951, with Bell test pilot Jean "Skip" Ziegler at the controls, the X-1D was launched over Rogers Dry Lake, on what was to become the only successful flight of its career. The unpowered glide was completed after a nine-minute descent, but upon landing, the nose landing gear failed and the aircraft slid ungracefully to a stop. Repairs took several weeks to complete and a second flight was scheduled for mid-August. On 22 August 1951, the X-1D was lost in a fuel explosion during preparations for the first powered flight. The aircraft was destroyed upon impact after it was jettisoned from its EB-50A mothership.[26]

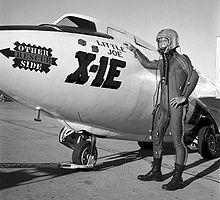

X-1E

(Bell Model 44)

The X-1E was the result of a reconstruction of the X-1-2 (serial 46-063), in order to pursue the goals originally set for the X-1D and X-1-3 (serial 46-064), both lost by explosions during 1951. The cause of the mysterious explosions was finally traced to the use of Ulmer leather[28] gaskets impregnated with tricresyl phosphate (TCP), a leather treatment, which was used in the liquid oxygen plumbing. TCP becomes unstable and explosive in the presence of pure oxygen and mechanical shock.[29] This mistake cost two lives, caused injuries and lost several aircraft.[30]

The changes included:

- A turbopump fuel feed system, which eliminated the high-pressure nitrogen fuel system used in '062 and '063. Concerns about metal fatigue in the nitrogen fuel system resulted in the grounding of the X-1-2 after its 54th flight in its original configuration.[31]

- A re-profiled super-thin wing (⅜ inches at the root), based on the X-3 Stiletto wing profile, enabling the X-1E to reach Mach 2.

- A 'knife-edge' windscreen replaced the original greenhouse glazing, an upward-opening canopy replaced the fuselage side hatch and allowed the inclusion of an ejection seat.

- The addition of 200 pressure ports for aerodynamic data, and 343 strain gauges to measure structural loads and aerodynamic heating along the wing and fuselage.[31]

The X-1E first flew on 15 December 1955, a glide-flight controlled by USAF test pilot Joe Walker. Walker left the X-1E program during 1958, after 21 flights, attaining a maximum speed of Mach 2.21 (752 m/s, 2,704 km/h). NACA research pilot John B. McKay took his place during September 1958, completing five flights in pursuit of Mach 3 (1,021 m/s, 3,675 km/h) before the X-1E was permanently grounded after its 26th flight, during November 1958, due to the discovery of structural cracks in the fuel tank wall.

Aircraft on display

- X-1-1, Air Force Serial Number 46-062, is currently displayed in the Milestones of Flight gallery of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, alongside the Spirit of St. Louis and SpaceShipOne. The aircraft was flown to Washington, D.C., beneath a B-29 and presented to what was then the American National Air Museum in 1950.[33]

- X-1B, AF Ser. No. 48-1385, is on display in the Research & Development Hangar at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

- X-1E, AF Ser. No. 46-063, is on display in front of the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center headquarters building at Edwards Air Force Base, California. It is usually seen in episodes of the TV series I Dream of Jeannie, which was set at Cape Kennedy, Florida.

Specifications (Bell X-1 #1 and #2)

Data from Bell Aircraft since 1935,[34] The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45[19]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 30 ft 11 in (9.42 m)

- X-1A, X-1B, X-1D: 35 ft 8 in (10.87 m)

- X-1C: 35.0 ft (10.67 m)

- Wingspan: 28 ft 0 in (8.53 m)

- X-1E: 22 ft 10 in (6.96 m)

- Height: 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m)

- Wing area: 130 sq ft (12 m2) </r>

- X-1E 115 sq ft (10.7 m2)

- Airfoil: #1 NACA 65-110 (10% thickness)

- #2, X-1A, X-1B, X-1D NACA 65-108 (8% thickness)

- X-1E NACA 64A004

- Empty weight: 7,000 lb (3,175 kg)

- X-1A, X-1B, X-1C, X-1D: 6,880 lb (3,120 kg)

- X-1E: 6,850 lb (3,110 kg)

- Gross weight: 12,250 lb (5,557 kg)

- X-1A, X-1B, X-1C, X-1D: 16,487 lb (7,478 kg)

- X-1E: 14,750 lb (6,690 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Reaction Motors XLR11-RM-3 4-chamber liquid-fuelled rocket engine, 6,000 lbf (27 kN) thrust

- X-1E: Reaction Motors RMI LR-8-RM-5 6,000 lbf (27 kN)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,612 mph (2,594 km/h, 1,401 kn)

- X-1E: 1,450 mph (1,260 kn; 2,330 km/h)

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.44

- X-1E: M2.24

- Endurance: 5 minutes powered flight

- X-1A, X-1B, X-1C, X-1D: 4 minutes 40 seconds powered flight

- X-1E: 4 minutes 45 seconds powered flight

- Service ceiling: 70,000 ft (21,000 m)

- X-1A, X-1B, X-1C, X-1D: 90,000 ft (27,000 m)

- X-1E: 75,000 ft (23,000 m)

Notable appearances in media

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of experimental aircraft

- List of rocket aircraft

- List of X-1 flights

- List of X-1A flights

- List of X-1B flights

- List of X-1D flights

- List of X-1E flights

- Air Force Test Center

References

Notes

- ^ a b Hallion, Richard, P. "The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier." Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved: 7 September 2011.

- ^ a b Wood 1975, p. 36.

- ^ Bancroft, Dennis. Secret History: "Breaking the Sound Barrier" Channel 4, 7 July 1997. Re-packaged as NOVA: "Faster Than Sound.", PBS, 14 October 1997. Retrieved: 26 April 2009.

- ^ Paur, Jason."Oct. 14, 1947: Yeager machs the sound barrier." Wired , 14 October 2009. Retrieved: 10 January 2016.

- ^ Miller 2001. [page needed]

- ^ Brown 1980, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f Ley, Willy (November 1948). "The 'Brickwall' in the Sky". Astounding Science Fiction. pp. 78–99.

- ^ Miller 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Yeager et al., 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Pisano, et al.. 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Miller, p. 23

- ^ Anderson, Clarence E. "Bud". "Initial Glide Flights." Archived March 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine cebudanderson.com. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ a b Yeager and Janos 1986

- ^ Wolfe 1979, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Anderson, Clarence E. "Bud". "A Turning Point." Archived April 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine cebudanderson.com. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ Powers, Sheryll Goeccke. "Women in Flight Research at NASA Dryden Flight Research Center from 1946 to 1995," Monographs in Aerospace History, Number 6, 1997, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D. C.

- ^ "Flights 'much faster than sound' confirmed by the U.S. Air Force". Milwaukee Journal. June 10, 1948. p. 1, part 1.

- ^ "Two U.S. planes fly faster than sound". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. June 11, 1948. p. 4.

- ^ a b Miller 2001, pp. 21–35.

- ^ Young, Dr. Jim. "Major Chuck Yeager's Flight to Mach 2.44 In the X-1A". Archived March 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine AFFTC History Office, Edwards AFB. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ^ Martin, Douglas |title=Arthur Murray. "Test Pilot, Is Dead at 92". The New York Times, 4 August 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ Miller 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Thompson, Lance. "The X-Hunters". Air & Space, February/March 1995, ISSN 0886-2257. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ Baugher, Joe. "USAAS-USAAC-USAAF-USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers – 1908 to Present." USAAS/USAAC/USAAF/USAF Aircraft Serials,20 January 2008. Retrieved: 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Photo number E-24911: X-1A in flight with flight data superimposed." Archived December 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine NASA Dryden. Retrieved: 14 October 2009.

- ^ "Fact Sheet X-1." NASA Dryden Fact Sheet. Retrieved: 12 March 2008.

- ^ Miller 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Made by the Ulmer Company. James R. Hansen, "First Man" p. 134

- ^ "Photo X-1A (E-24911)." Archived September 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine NASA (Dryden Collections). Retrieved: 5 January 2016.

- ^ Lockett, Brian. "Edwards Air Force Base History: Bell X-1 Explosions." Goleta Air and Space Museum, 3 July 1998. Retrieved: 5 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Fact sheet: X-1E." NASA (Dryden Collections). Retrieved: 5 January 2016..

- ^ "Bell X-1". si.edu. 21 March 2016.

- ^ Staff, "Resting Place", Flight, 28 September 1950, page 350.

- ^ Pelletier, Alain J. (1992). Bell Aircraft since 1935 (1st ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 83–90. ISBN 1-55750-056--8.

Bibliography

- "Breaking the Sound Barrier". Modern Marvels (TV program). 2003.

- Hallion, Dr. Richard P. "Saga of the Rocket Ships". AirEnthusiast Five, November 1977 – February 1978. Bromley, Kent, UK: Pilot Press Ltd., 1977.

- Miller, Jay. The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45. Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-109-1.

- Pisano, Dominick A., R. Robert van der Linden and Frank H. Winter. Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1: Breaking the Sound Barrier. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (in association with Abrams, New York), 2006. ISBN 0-8109-5535-0.

- Winchester, Jim. "Bell X-1". Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft (The Aviation Factfile). Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2005. ISBN 978-1-59223-480-6.

- Wolfe. Tom. The Right Stuff. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. ISBN 0-374-25033-2.

- Yeager, Chuck, Bob Cardenas, Bob Hoover, Jack Russell and James Young. The Quest for Mach One: A First-Person Account of Breaking the Sound Barrier. New York: Penguin Studio, 1997. ISBN 0-670-87460-4.

- Yeager, Chuck and Leo Janos. Yeager: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam, 1986. ISBN 0-553-25674-2.

External links

- Bell X-1B – National Museum of the United States Air Force

- X-1 fiftieth anniversary – NASA

- Chalmers H. (Slick) Goodlin – NASA

- American X-Vehicles – An Inventory—X-1 to X-50 – NASA

- Bell X-1 – National Air and Space Museum

- General Chuck Yeager | The Official Website

- Modeller's Guide to Bell X-1 Experimental Aircraft Part one, Part two

- X-1 is Carried Aloft; Cockpit of the Bell X-1 – Popular Science

- NASA video collection