Tube (structure)

In structural engineering, the tube is a system where, to resist lateral loads (wind, seismic, impact), a building is designed to act like a hollow cylinder, cantilevered perpendicular to the ground. This system was introduced by Fazlur Rahman Khan while at the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), in their Chicago office.[1] The first example of the tube’s use is the 43-story Khan-designed DeWitt-Chestnut Apartment Building, since renamed Plaza on DeWitt, in Chicago, Illinois, finished in 1966.[2]

The system can be built using steel, concrete, or composite construction (the discrete use of both steel and concrete). It can be used for office, apartment, and mixed-use buildings. Most buildings of over 40 stories built since the 1960s are of this structural type.

Concept

The tube system concept is based on the idea that a building can be designed to resist lateral loads by designing it as a hollow cantilever perpendicular to the ground. In the simplest incarnation of the tube, the perimeter of the exterior consists of closely spaced columns that are tied together with deep spandrel beams through moment connections. This assembly of columns and beams forms a rigid frame that amounts to a dense and strong structural wall along the exterior of the building.[3]

This exterior framing is designed sufficiently strong to resist all lateral loads on the building, thereby allowing the interior of the building to be simply framed for gravity loads. Interior columns are comparatively few and located at the core. The distance between the exterior and the core frames is spanned with beams or trusses and can be column-free. This maximizes the effectiveness of the perimeter tube by transferring some of the gravity loads within the structure to it, and increases its ability to resist overturning via lateral loads.

History

By 1963, a new structural system of framed tubes had appeared in skyscraper design and construction. Fazlur Rahman Khan, a structural engineer from Bangladesh (then called East Pakistan) who worked at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, defined the framed tube structure as "a three dimensional space structure composed of three, four, or possibly more frames, braced frames, or shear walls, joined at or near their edges to form a vertical tube-like structural system capable of resisting lateral forces in any direction by cantilevering from the foundation."[4] Closely spaced interconnected exterior columns form the tube. Lateral or horizontal loads (wind, seismic, impact) are supported by the structure as a whole. About half the exterior surface is available for windows. Framed tubes require fewer interior columns, and so allow more usable floor space. Where larger openings like garage doors are needed, the tube frame must be interrupted, with transfer girders used to maintain structural integrity.

Khan's tube concept was inspired by his hometown in Dhaka, Bangladesh. His hometown did not have any buildings taller than three stories. He also did not see his first skyscraper in person until the age of 21 years old, and he had not stepped inside a mid-rise building until he moved to the United States for graduate school. Despite this, the environment of his hometown in Dhaka later influenced his tube building concept, which was inspired by the bamboo that sprouted around Dhaka. He found that a hollow tube, like the bamboo in Dhaka, lent a high-rise vertical durability.[5]

The first building to apply the tube-frame construction was the DeWitt-Chestnut Apartment Building which Khan designed and which was finished in Chicago by 1963.[6] This laid the foundations for the tube structural design of many later skyscrapers, including his own John Hancock Center and Willis Tower, and the construction of the World Trade Center, Petronas Towers, Jin Mao Building, and most other supertall skyscrapers since the 1960s, including the world's tallest building as of 2017[update], the Burj Khalifa.[7]

Variants

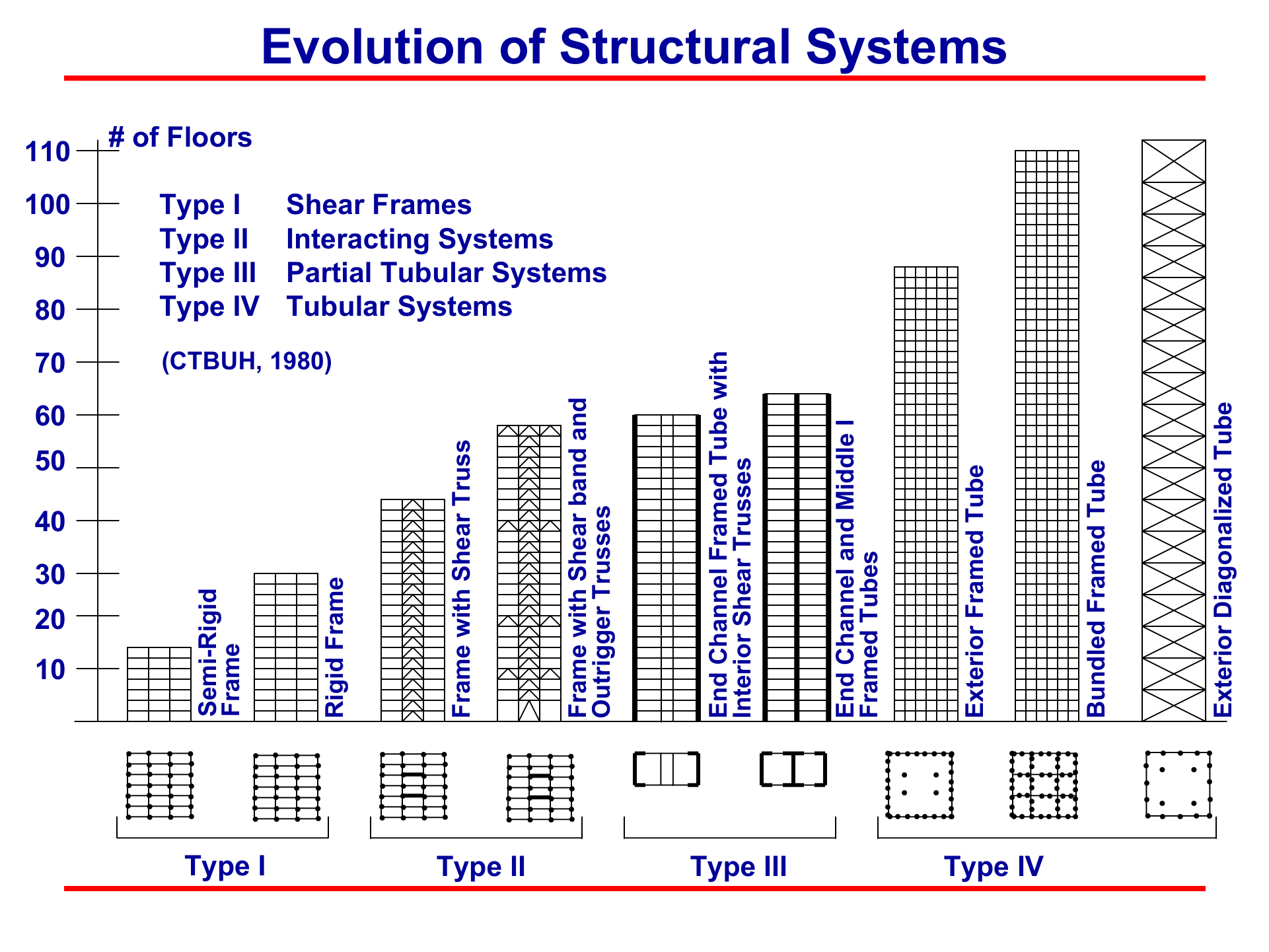

From its conception, the tube has been varied to suit different structural needs.

Framed tube

This is the simplest incarnation of the tube. It can appear in a variety of floor plan shapes, including square, rectangular, circular, and freeform. This design was first used in Chicago's DeWitt-Chestnut Apartment Building, designed by Khan and finished in 1965, but the most notable examples are the Aon Center and the original World Trade Center towers.

Trussed or braced tube

The trussed tube, also termed braced tube, is similar to the simple tube but with comparatively fewer and farther-spaced exterior columns. Steel bracings or concrete shear walls are introduced along the exterior walls to compensate for the fewer columns by tying them together. The most notable examples incorporating steel bracing are the John Hancock Center, the Citigroup Center, and the Bank of China Tower.

Tube in tube

Also known as hull and core, these structures have a core tube inside the structure, holding the elevator and other services, and another tube around the exterior. Most of the gravity and lateral loads are normally taken by the outer tube because of its greater strength. The 780 Third Avenue 50-story concrete frame office building in Manhattan uses concrete shear walls for bracing and an off-center core to allow column-free interiors.[8]

Bundled tube

Instead of one tube, a building consists of several tubes tied together to resist lateral forces. Such buildings have interior columns along the perimeters of the tubes when they fall within the building envelope. Notable examples include Willis Tower, One Magnificent Mile, and the Newport Tower.

Beside being efficient structurally and economically, the bundled tube was "innovative in its potential for versatile formulation of architectural space. Efficient towers no longer had to be box-like; the tube-units could take on various shapes and could be bundled together in different sorts of groupings."[9] The bundled tube structure meant that "buildings no longer need be boxlike in appearance: they could become sculpture."[10]

Hybrids

Hybrids include a varied category of structures where the basic concept of tube is used, and supplemented by other structural support(s). This method is used where a building is so thin that one system cannot provide adequate strength or stiffness.

Concrete tube structures

The last major buildings engineered by Khan were the One Magnificent Mile and Onterie Center in Chicago, which employed his bundled tube and trussed tube system designs respectively. In contrast to his earlier buildings, which were mainly steel, his last two buildings were concrete. His earlier DeWitt-Chestnut Apartments building, built in 1963 in Chicago, was also a concrete building with a tube structure.[7] Trump Tower in New York City is also another example that adapted this system.[11]

Other uses

Some lattice towers consist of steel tube elements. They can be used for guyed and for free-standing lattice structures. An example for the first type was Warsaw Radio Mast, an example for latter one are the Russian 3803 KM-towers.

Diagram

References

- ^ Weingardt, Richard (2005). Engineering Legends. ASCE Publications. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-7844-0801-8.

- ^ Beedle, Lynn S.; Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (1986). Advances in tall buildings. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-442-21599-6.

- ^ Ali, Mir M.; Moon, Kyoung Sun (2007). "Structural Developments in Tall Buildings: Current Trends and Future Prospects". Architectural Science Review. 50 (3): 205–223. doi:10.3763/asre.2007.5027.

- ^ "Evolution of Concrete Skyscrapers". Archived from the original on 2007-06-05. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ Greene, Nick (28 June 2016). "The Man Who Saved the Skyscraper". Mental Floss. Atavist. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Swenson, Alfred; Chang, Pao-Chi (2008). "Building construction". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ^ a b Ali, Mir M. (2001). "Evolution of Concrete Skyscrapers: from Ingalls to Jin Mao". Electronic Journal of Structural Engineering. 1 (1): 2–14. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- ^ 780 Third Avenue at Emporis

- ^ Hoque, Rashimul (2012). "Khan, Fazlur Rahman1". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Stephen Bayley (5 January 2010). "Burj Dubai: The new pinnacle of vanity". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ^ Seinuk, Ysrael A.; Cantor, Irwin G. (March 1984). "Trump Tower: Concrete Satisfies Architectural, design, and construction demands". Concrete International. 6 (3): 59–62. ISSN 0162-4075.