Conquest of Space

| Conquest of Space | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Byron Haskin |

| Screenplay by | James O'Hanlon |

| Produced by | George Pal |

| Starring | Walter Brooke Eric Fleming Mickey Shaughnessy |

| Cinematography | Lionel Lindon |

| Edited by | Everett Douglas |

| Music by | Nathan Van Cleave |

Production company | Paramount Pictures Corp. |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 81 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1 million (US)[1] |

Conquest of Space is a 1955 American Technicolor science fiction film from Paramount Pictures, produced by George Pal, directed by Byron Haskin, that stars Walter Brooke, Eric Fleming, and Mickey Shaughnessy.

The film's storyline concerns the first interplanetary flight to the planet Mars, manned by a crew of five, and launched from Earth orbit near "The Wheel", mankind's first space station. On their long journey to the Red Planet, they encounter various dangers, both from within and without, that nearly destroy the mission.

Plot

Mankind has achieved space flight capability and built "The Wheel" space station in orbit 1,075 miles (1,730 km) above Earth. It is commanded by its designer, Colonel Samuel T. Merritt. His son, Captain Barney Merritt, having been aboard for a year, wants to return to Earth.

A giant spaceship has been built in a nearby orbit, and an Earth inspector arrives aboard the station with new orders: Merritt Sr. is being promoted to general and will command the new spaceship, now being sent to Mars instead of the Moon. As General Merritt considers his crew of three enlisted men and one officer, his close friend, Sgt. Mahoney volunteers. The general turns him down for being 20 years too old. Hearing that Mars is the new destination, Barney Merritt volunteers to be the second officer.

Right after the crew watches a TV broadcast from their family and friends, the mission blasts off for the Red Planet. The general's undiagnosed and growing space fatigue is beginning to seriously affect his judgement: reading his Bible frequently, he has doubts about the righteousness of the mission. After launch, Sgt. Mahoney is discovered to be a stowaway, having hidden in a crew spacesuit. Their piloting radar antenna later fails, and two crewmen go outside to make repairs. They manage to get it working just as their monitors show a glowing planetoid, 20 times larger than their spaceship, coming at them from astern. The general fires the engines, barely managing to avoid a collision, but the planetoid's fast-orbiting debris punctures Sgt. Fodor's spacesuit, killing him instantly. After a religious service in space, Fodor's body is cast adrift into the void.

Eight months later, the general is becoming increasingly mentally unbalanced, focusing on Sgt. Fodor's loss as "God's judgement". On the Mars landing approach, he attempts to crash their spaceship, now convinced the mission violates the laws of God. Barney wrests control away from his father, landing the large flying wing glider-rocket safely. Later, as the crew takes their first steps on the Red Planet, they look up and see water pouring down from the now vertical return rocket. Barney quickly discovers the leak is sabotage caused by his father, who threatens his son with a .45 automatic. The two struggle and the pistol discharges, killing the general. Sgt. Mahoney, who observed only the last stages of the struggle, wants Barney confined under arrest with the threat of court martial, but cooler heads prevail; Barney becomes the ranking officer.

Mars proves to be inhospitable, and they struggle to survive with their decreased water supply. Earth's correct orbital position for a return trip is one year away. While glumly celebrating their first Christmas on Mars, a sudden snowstorm blows in, allowing them to replenish their water supply. As their launch window arrives, they hear low rumbling sounds, then see rocks falling, and feel the ground shake violently. The ground level shifts during this violent marsquake. Their spaceship is now leaning at a precarious angle and cannot make an emergency blast off. To right the spaceship, the crew uses the rocket engines' powerful thrust to shift the ground under the landing legs. The attempt works and they blast off, the spaceship rising just as the Martian surface completely collapses.

Once in space, Barney and Mahoney reconcile. Impressed with Barney's heroism and leadership while on Mars, Mahoney concludes that pursuing Barney's court martial for his father's death would only impugn the general's reputation, tarnishing what previously had been a spotless military career. Better is the fiction that "the man who conquered space" died in the line of duty, sacrificing himself to save his crew.

Cast

- Walter Brooke as General Samuel T. Merritt

- Eric Fleming as Captain Barney Merritt

- Mickey Shaughnessy as Sgt. Mahoney

- Phil Foster as Sgt. Jackie Seigel

- William Redfield as Roy Cooper

- William Hopper as Dr. George Fenton

- Benson Fong as Sgt. Imoto

- Ross Martin as Sgt. Andre Fodor

- Vito Scotti as Sanella

- John Dennis as Donkersgoed

- Michael Fox as Elsbach

- Joan Shawlee as Rosie

- Iphigenie Catiglioni as Mrs. Fodor

- Rosemary Clooney uncredited appearance

Production

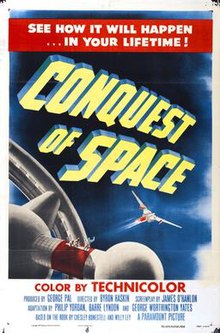

The science and technology portrayed in Conquest of Space were intended to be as realistic as possible in depicting the first voyage to Mars. The film's theatrical release poster tagline reads: "See how it will happen ... in your lifetime!" [2]

The title Conquest of Space is from the 1949 nonfiction book The Conquest of Space, written by Willy Ley and illustrated by Chesley Bonestell. George Pal bought the book's film rights at the suggestion of Ley.[3] Bonestell, noted for his photorealistic paintings showing views from outer space, worked on the film's space matte paintings.[2] The production design of Conquest of Space was closely modeled on the technical concepts of Wernher von Braun and Bonestell's space paintings, which originally appeared in Collier's magazine and were reprinted in the 1952 Viking Press book Across the Space Frontier, edited by Cornelius Ryan.[4]

The film also incorporated concepts from von Braun's 1952 book The Mars Project, as well as material appearing in the April 30, 1954, issue of Collier's magazine, "Can we get to Mars?" by von Braun, with Cornelius Ryan. This would later be incorporated into the 1956 Viking Press book The Exploration of Mars by Willy Ley, Wernher von Braun, and Chesley Bonestell.[4] All of these books mainly feature text that is straight popular science, with no fictional characters or story line.[2] In addition, according to director Byron Haskin, "We had Wernher von Braun on the set all the time...as a technical advisor".[5][4]

Had George Pal followed any or all of these nonfiction books as written, he would have produced a speculative futuristic documentary, much like of the trio of 1955 Tomorrowland-set (Walt Disney's) Disneyland television episodes: Man in Space, Man and the Moon, and Mars and Beyond. The final screenplay by James O'Hanlon, from an adaptation by Philip Yordan, Barré Lyndon, and George Worthing Yates, instead creates a fictional story from whole cloth.[2]

Reception

Critical response upon release

Judgments on the quality of the film's special effects have varied. Upon the film's release, reviewer Oscar A. Godbout in his review for The New York Times praised the effects, but was disparaging of the storyline, noting "... as plots go...it is not offensive".[6]

Later critiques

Film authority Roy Kinnard says, “In examining the plethora of 1950s science-fiction movies which deal with the theme of mans’ journeying to other worlds in order to advance his own knowledge, George Pal’s production of Conquest of Space stands head and shoulders above the others.... [I]n a ... genre overburdened with cheap and shoddy productions that are all too deserving of scorn, Conquest of Space rises above the tide of mediocrity. ... [T]he special visual effects in Conquest ... are outstanding for their time ... and they are the well-tailored work of one of Hollywood’s most gifted craftsmen, John P. Fulton. Besides the massive, graceful spacecraft shown in this film, it was Fulton who was responsible for parting the Red Sea in the 1956 version of The Ten Commandments. ... It is true that the blue screen mattes in Conquest are crude [from our perspective] ... but this is hardly a technical flaw unique to this picture. Many productions of the 50s had difficulty with blue screen work, even multi-million dollar spectaculars like Ben-Hur”.[7] Furthermore, science fiction film authority Thomas Kent Miller states, "Blue screen was used extensively in this epic [The Ten Commandments], and the blue line fringes are always quite evident throughout the movie. In fact, Fulton’s remarkable and iconic Parting of the Red Sea sequence is a great hodgepodge of intersecting blue fringe lines".[8]

British film critic John Baxter, in his 1970 volume, Science Fiction in the Cinema, states, “Conquest of Space ... gave [George] Pal and [Byron] Haskin an excuse to show realistic take-offs, space maneuverings, and a landing on Mars ... achieved with some flair. Drama in the shape of a religious maniac at the helm detracts little from the essential narrative, and some of the detail is clever, such as the space burial with the suited corpse sliding slowly on a long fall into the sun".[9]

Modern audiences are apt to notice the presence of matte lines. Reviewer Glenn Erickson said that "the ambitious special effects were some of the first to garner jeers for their lack of realism". Erickson correctly assesses the film as "a flop that seriously hindered George Pal's career as a producer".[10] [10] Paul Brenner said, "Pal pulls out all stops in the special effects department, creating 'The Wheel', rocket launches into space, and a breathtaking near collision with an asteroid".[citation needed] The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction said "The special effects are quite ambitious but clumsily executed, in particular the matte work".[11] Paul Corupe said that often "the overall image on screen that inspires awe: the Martian landscape, the general's high-tech office, and the vastness of the cosmos. The film's budget is certainly up on screen for your entertainment, but it's just spectacle for spectacle's sake". He, too, complains of matte lines, but acknowledges, "the composites are convincing enough for the time the film was made".[12] Corupe described it as the "first big flop in Pal's career. It was a major setback that saw him abandon science fiction filmmaking for five years, including a planned sequel to When Worlds Collide"[12] The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction remarks "A truly awful film, Conquest of Space is probably George Pal's worst production".[11]

Academy Award winner Dennis Muren offers a memory of 1955: “[M]y pal Bruce and I hurried into the Hawaii Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard to see a new color movie, Conquest of Space. We were eight years old. ... ‘Reeling’ by on the giant screen, we saw a giant circular space station in orbit one hundred [sic] miles up, seemingly in orbit above me over Hollywood. Wow! And that was just the beginning. Awesome rocket ships of various shapes flew about. ... Finally, the movie ended with a skillful landing and joyful liftoff from the desolate red surface of Mars. ...”[13]

The film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes currently rates the film at 60% ("Fresh").[14]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "The Top Box-Office Hits of 1955". Variety Weekly, January 25, 1956.

- ^ a b c d Warren 1982 pp. 208-214

- ^ Hickman 1977 p. 87

- ^ a b c Miller 2016, pp. 60-69.

- ^ Haskin, Byron. Byron Haskin: An Interview by Joe Adamson. Metuchen, New Jersey: The Directors Guild of America and Scarecrow Press, 1984, p. 230.

- ^ Goodbout, Oscar A. (O.A.G.). "Special Effects Show: 'Conquest of Space'." The New York Times, May 28, 1955.

- ^ Kinnard, Roy. “A New Look at an Old Classic: Conquest of Space” in Fantastic Films: The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in the Cinema, Volume 2, Number 2. Chicago: Blake Publishing Corp., June 1979

- ^ Miller 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Baxter, John. Science Fiction in the Cinema. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1970.

- ^ a b Erickson, Glenn. "Review: Conquest of Space." DVD Savant, October 30, 2004. Retrieved: January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Conquest of Space, The." The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, March 22, 2012. Retrieved: January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Corupe, Paul. "Review: 'Conquest of Space'." Archived 2004-12-04 at the Wayback Machine DVD Verdict, November 26, 2004. Retrieved: January 14, 2015.

- ^ Muren, Dennis. “Foreword” in Modern Sci-Fi Films FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About Time Travel, Alien, Robot, and Out-of-This-World Movies Since 1970 by Tom DeMichael. Milwaukee, WI: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2014.

- ^ "Ratings: 'Conquest of Space'." Rotten Tomatoes, 2015. Retrieved: May 15, 2015.

Bibliography

- Baxter, John. Science Fiction in the Cinema. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1970.

- DeMichael, Tom. Modern Sci-Fi Films FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About Time Travel, Alien, Robot, and Out-of-This-World Movies Since 1970. Milwaukee, WI: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2014.

- Haskin, Byron. Byron Haskin: An Interview by Joe Adamson. Metuchen, New Jersey: The Directors Guild of America and Scarecrow Press, 1984. ISBN 0-8108-1740-3.

- Hickman, Gail Morgan. The Films of George Pal. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1977. ISBN 0-498-01960-8.

- Kinnard, Roy. “A New Look at an Old Classic: Conquest of Space” in Fantastic Films: The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in the Cinema, Volume 2, Number 2. Chicago: Blake Publishing Corp., June 1979.

- Ley, Willy. The Conquest of Space. New York: Viking, 1949. Pre-ISBN era.

- Ley, Willy, Wernher von Braun and Chesley Bonestell. The Exploration of Mars. New York: Viking Press, 1956. ASIN: B0000CJKQN

- Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Ryan, Cornelius (ed.). Across the Space Frontier. Essays by Joseph Kaplan, Wernher Von Braun, Heinz Haber, Willy Ley, Oscar Schachter, Fred L. Whipple; Illustrations by Chesley Bonestell, Rolf Klep, Fred Freeman. New York: Viking Press, 1952. ASIN: B0000CIFLX.

- Strick, Philip. Science Fiction Movies. London: Octopus Books Limited, 1976. ISBN 0-7064-0470-X.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies, Vol. I: 1950–1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.