Course (orienteering)

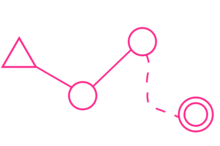

An orienteering course is composed of a start point, a series of control points, and a finish point. Controls are marked with a white and orange flag in the terrain, and corresponding purple symbols on an orienteering map. The challenge is to complete the course by visiting all control points in the shortest possible time, aided only by the map and a compass.[1]

Course types and lengths

Courses can have varying degrees of difficulty, both technical and physical. Courses for children and novices are made easy, while experienced competitors may face extremely challenging courses. Technical difficulty is determined primarily by the terrain and the navigational problems of crossing that terrain to locate the feature on which the control is placed. Linear features such as fences, walls, and paths generally offer low difficulty; natural features such as forest or open moor can offer high difficulty. Physical difficulty is determined by the length of the course, the amount of climb, and the kinds of terrain (rocky, boggy, undergrowth etc.). General guidelines for orienteering courses are available from the International Orienteering Federation[1] and national orienteering sport bodies.

Both the British Orienteering Federation (BOF) and Orienteering USA (OUSA) have formal systems that define levels of technical difficulty. The BOF system has 5 levels whereas the OUSA system has 7. In both systems, novices start on a course with a technical and physical difficulty of 1 and progress according to their age, experience, and ability up to a course with a technical and physical difficulty of 5. Great care is taken to ensure that developing juniors are provided with a course that gives them a satisfying challenge without pushing them beyond their current ability.[2]

Advanced courses can be divided into long distance, middle distance and sprint. For instance, a long course can have expected winning times up to 100 minutes (elite men), or 80 minutes (elite women), while a sprint course will have expected winning times 12–15 minutes. As competitor speed is dependent on the terrain there is no fixed distance for course lengths, instead the course length is derived from an expected winning time, and the actual course length will vary according to the difficulty of the terrain and expected fitness of the best participants.

Relay

In a relay, all teams run the same overall course, with each team member running a part of the overall course. Different teams will run the course in a different order e.g. if the overall course consists of parts A, B, and C, teams may run ABC, BCA, or CAB.[1]

Course planning

When designing a course, the aim is to present a course that is suited to the ability of the competitor, and such that orienteering skills (fast map reading, running in rough terrain, finding the best route, etc.) rather than luck most likely will decide the outcome of the competition. A fair course requires a reliable map, unambiguous control points, accurate placement of control points on the map, and good and challenging course legs between the control points.

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2017) |

For International and National events courses are provided according to the age of the competitor e.g. M21E is a course for men aged over 21 and who are classed as 'elite'. For other events a simplified structure is used: both the British Orienteering Federation (BOF) and Orienteering USA (OUSA) have guidelines for these courses which incorporate the levels of technical difficulty. The BOF system has 5 levels of technical difficulty and the OUSA system has 3. In both systems, White courses have the least technical challenge, followed by Yellow and Orange. In both systems, all other courses (Red, Blue, Green, Brown, Black) are for advanced competitors and vary only in their degree and kind of physical challenge. In the BOF system, White and Yellow together correspond to OUSA White; Orange corresponds more or less to OUSA Yellow; and Light Green corresponds to OUSA Orange.[3][4][5]

In OUSA, the guidelines for designing course levels are as follows:

White—2-3 kilometers, winning time: 25-30 min., age up to 12

Control points should be close together, large and very easy (f.ex. trail junctions). The path should be along linear features, like trails, roads and stone walls. No compass needed. No route choice necessary. The most common complaint is that the white course was too hard. It's not unusual for an 8-year-old to be doing the course on their own. Especially the first controls should be easy.

Yellow—3-5 kilometers, 35–40 minutes, age 13-14 and novices

The basic course should be along linear features, but the controls should be large and set back 25-50m from a linear feature. Limited compass use. Legs should be 200-600m. The first couple controls should be especially easy to allow people to familiarize themselves with the map.

Orange—4.5-7 kilometers, 50-55 min., intermediate

Controls should be moderately difficult. Navigation should not be primarily along paths. A compass is necessary. Course choice is actively encouraged. However, every control should be within 100m of an attack point, or obvious feature, and beyond the control should be a linear catch feature, so that the runner knows when s/he has gone too far. On no more than two legs should navigation rely solely on compass and counting paces. Orange course are often perceived as much more difficult than yellow. Once you can reliably complete orange courses, you have learned the basic skill.

There is also a Green course, Brown, Red, and Blue in the U.S. Yellow, Orange and Green are the only ones available to the JROTC branches, and are the usual choices for most civilians.

There is generally almost no overlap between white, yellow and orange controls. The requirements of each are fundamentally different. However, for brown, green, red and blue courses, the control requirements are basically the same. The advanced courses differ in length and degree of strenuousness. Finding the controls should require skill rather than luck. They should therefore be placed at a small identifiable feature—depressions, knolls, small reentrants—not in the middle of a field of tall grass, but also not too close to the top of a hill that anyone can find. Try to avoid legs which just require physical effort but no skill. Place controls before linear features instead of after them so that more skilled navigators have an advantage. Legs should be shorter if you don't follow linear features and should be no closer than 200m to a linear feature. At least one leg should be around 800m. Route choice should be maximized to favor those who choose the best routes. Often brown and green courses are run by older, but skilled orienteers. Therefore, steep inclines should be avoided. Vision and eye injury is a consideration on these courses.

Computer software is available which helps in the planning of courses and can be used for pre-printing courses on orienteering maps. Current software includes Condes, and OCAD.

References

- ^ a b c "Competition rules for International Orienteering Federation (IOF) foot orienteering events (2008)" (PDF). International Orienteering Federation. Retrieved 2008-09-30.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Barry Elkington (2009). "Planning the Orange course (editorial preface)" (PDF). Orienteering North America: Covering Map and Compass Sports in the U.S. & Canada (August/September): 25–27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) The author's draft, relevant to BOF courses, without the editorial preface and other changes relevant to USOF (now OUSA) courses, is available on the web. As in the USOF/OUSA system, all other courses are advanced. - ^ Barry Elkington (2009). "Planning the Orange course". Orienteering North America: Covering Map and Compass Sports in the U.S. & Canada (August/September): 25–27.

- ^ Barry Elkington. "Planning the Orange course" (PDF). British Orienteering Federation. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "Event Guideline B: Regional & Local Cross Country Events (January 2009 Draft)" (PDF). British Orienteering Federation. Retrieved 2009-09-09.[permanent dead link]