Doctor Who season 1

| Doctor Who | |

|---|---|

| Season 1 | |

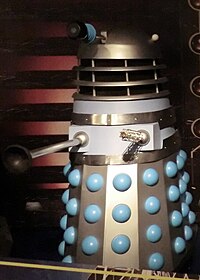

Cover art of the Region 2 DVD release for first serial of the season | |

| Starring | |

| No. of stories | 8 |

| No. of episodes | 42 (9 missing) |

| Release | |

| Original network | BBC TV / BBC1[a] |

| Original release | 23 November 1963 – 12 September 1964 |

| Season chronology | |

The first season of British science fiction television programme Doctor Who was originally broadcast on BBC TV[a] between 1963 and 1964. The series began on 23 November 1963 with An Unearthly Child and ended with The Reign of Terror on 12 September 1964. The show was created by BBC Television head of drama Sydney Newman to fill the Saturday evening timeslot and appeal to both the younger and older audiences of the neighbouring programmes. Formatting of the programme was handled by Newman, head of serials Donald Wilson, writer C. E. Webber, and producer Rex Tucker. Production was overseen by the BBC's first female producer Verity Lambert and story editor David Whitaker, both of whom handled the scripts and stories.

The season introduces William Hartnell as the first incarnation of the Doctor, an alien who travels through time and space in his TARDIS, which appears to be a British police box on the outside. Carole Ann Ford is also introduced as the Doctor's granddaughter Susan Foreman, who acts as his companion alongside her schoolteachers Ian Chesterton and Barbara Wright, portrayed by William Russell and Jacqueline Hill, respectively. Throughout the season, the Doctor and his companions travel throughout history and into the future. Historical stories were intended to educate viewers about significant events in history, such as the Aztec civilisation and the French Revolution; futuristic episodes took a more subtle approach to educating viewers, such as the theme of pacifism with the Daleks.

The first eight serials were written by six writers: Whitaker, Anthony Coburn, Terry Nation, John Lucarotti, Peter R. Newman, and Dennis Spooner. Webber also co-wrote the show's first episode. The show was developed with three particular story types envisioned: past history, future technology, and alternative present; Coburn, Lucarotti, and Spooner wrote historical episodes, Nation and Newman penned futuristic stories, and Whitaker wrote a "filler" serial set entirely in the TARDIS. The serials were mostly directed by junior directors, such as Waris Hussein, John Gorrie, John Crockett, Henric Hirsch, Richard Martin, Christopher Barry, and Frank Cox; the exception is experienced director Mervyn Pinfield, who directed the first four episodes of The Sensorites. Filming started in September 1963 and lasted for approximately nine months, with weekly recording taking place mostly at Lime Grove Studios or the BBC Television Centre.

The first episode, overshadowed by the assassination of John F. Kennedy the previous day, was watched by 4.4 million viewers; the episode was repeated the following week, and the programme gained popularity with audiences, particularly with the introduction of the Daleks in the second serial, which peaked at 10.4 million viewers. The season received generally positive reviews, with praise particularly directed at the scripts and performances. However, many retrospective reviewers noted that Susan lacked character development and was generally portrayed as a damsel in distress, a criticism often echoed by Ford. Several episodes were erased by the BBC between 1967 and 1972, and only 33 of a total of 42 episodes survive; all seven episodes of Marco Polo and two episodes of The Reign of Terror remain missing. The existing serials received several VHS and DVD releases as well as tie-in novels.

Serials

| Story | Serial | Serial title | Episode titles | Directed by | Written by | Original air date | Prod. code | UK viewers (millions) [2] | AI [2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | An Unearthly Child | "An Unearthly Child" | Waris Hussein | Anthony Coburn and C. E. Webber (uncredited) | 23 November 1963 | A | 4.4 | 63 |

| "The Cave of Skulls" | Waris Hussein | Anthony Coburn | 30 November 1963 | 5.9 | 59 | ||||

| "The Forest of Fear" | Waris Hussein | Anthony Coburn | 7 December 1963 | 6.9 | 56 | ||||

| "The Firemaker" | Waris Hussein | Anthony Coburn | 14 December 1963 | 6.4 | 55 | ||||

| 2 | 2 | The Daleks | "The Dead Planet" | Christopher Barry | Terry Nation | 21 December 1963 | B | 6.9 | 59 |

| "The Survivors" | Christopher Barry | Terry Nation | 28 December 1963 | 6.4 | 58 | ||||

| "The Escape" | Richard Martin | Terry Nation | 4 January 1964 | 8.9 | 63 | ||||

| "The Ambush" | Christopher Barry | Terry Nation | 11 January 1964 | 9.9 | 63 | ||||

| "The Expedition" | Christopher Barry | Terry Nation | 18 January 1964 | 9.9 | 63 | ||||

| "The Ordeal" | Richard Martin | Terry Nation | 25 January 1964 | 10.4 | 63 | ||||

| "The Rescue" | Richard Martin | Terry Nation | 1 February 1964 | 10.4 | 65 | ||||

| 3 | 3 | The Edge of Destruction | "The Edge of Destruction" | Richard Martin | David Whitaker | 8 February 1964 | C | 10.4 | 61 |

| "The Brink of Disaster" | Frank Cox | David Whitaker | 15 February 1964 | 9.9 | 60 | ||||

| 4 | 4 | Marco Polo | "The Roof of the World"† | Waris Hussein | John Lucarotti | 22 February 1964 | D | 9.4 | 63 |

| "The Singing Sands"† | Waris Hussein | John Lucarotti | 29 February 1964 | 9.4 | 62 | ||||

| "Five Hundred Eyes"† | Waris Hussein | John Lucarotti | 7 March 1964 | 9.4 | 62 | ||||

| "The Wall of Lies"† | John Crockett | John Lucarotti | 14 March 1964 | 9.9 | 60 | ||||

| "Rider from Shang-Tu"† | Waris Hussein | John Lucarotti | 21 March 1964 | 9.4 | 59 | ||||

| "Mighty Kublai Khan"† | Waris Hussein | John Lucarotti | 28 March 1964 | 8.4 | 59 | ||||

| "Assassin at Peking"† | Waris Hussein | John Lucarotti | 4 April 1964 | 10.4 | 59 | ||||

| 5 | 5 | The Keys of Marinus | "The Sea of Death" | John Gorrie | Terry Nation | 11 April 1964 | E | 9.9 | 62 |

| "The Velvet Web" | John Gorrie | 18 April 1964 | 9.4 | 60 | |||||

| "The Screaming Jungle" | John Gorrie | 25 April 1964 | 9.9 | 61 | |||||

| "The Snows of Terror" | John Gorrie | 2 May 1964 | 10.4 | 60 | |||||

| "Sentence of Death" | John Gorrie | 9 May 1964 | 7.9 | 61 | |||||

| "The Keys of Marinus" | John Gorrie | 16 May 1964 | 6.9 | 63 | |||||

| 6 | 6 | The Aztecs | "The Temple of Evil" | John Crockett | John Lucarotti | 23 May 1964 | F | 7.4 | 62 |

| "The Warriors of Death" | John Lucarotti | 30 May 1964 | 7.4 | 62 | |||||

| "The Bride of Sacrifice" | John Lucarotti | 6 June 1964 | 7.9 | 57 | |||||

| "The Day of Darkness" | John Lucarotti | 13 June 1964 | 7.4 | 58 | |||||

| 7 | 7 | The Sensorites | "Strangers in Space" | Mervyn Pinfield | Peter R. Newman | 20 June 1964 | G | 7.9 | 59 |

| "The Unwilling Warriors" | Mervyn Pinfield | Peter R. Newman | 27 June 1964 | 6.9 | 59 | ||||

| "Hidden Danger" | Mervyn Pinfield | Peter R. Newman | 11 July 1964 | 7.4 | 56 | ||||

| "A Race Against Death" | Mervyn Pinfield | Peter R. Newman | 18 July 1964 | 5.5 | 60 | ||||

| "Kidnap" | Frank Cox | Peter R. Newman | 25 July 1964 | 6.9 | 57 | ||||

| "A Desperate Venture" | Frank Cox | Peter R. Newman | 1 August 1964 | 6.9 | 57 | ||||

| 8 | 8 | The Reign of Terror | "A Land of Fear" | Henric Hirsch | Dennis Spooner | 8 August 1964 | H | 6.9 | 58 |

| "Guests of Madame Guillotine" | Dennis Spooner | 15 August 1964 | 6.9 | 54 | |||||

| "A Change of Identity" | Dennis Spooner | 22 August 1964 | 6.9 | 55 | |||||

| "The Tyrant of France"† | Dennis Spooner | 29 August 1964 | 6.4 | 53 | |||||

| "A Bargain of Necessity"† | Dennis Spooner | 5 September 1964 | 6.9 | 53 | |||||

| "Prisoners of Conciergerie" | Dennis Spooner | 12 September 1964 | 6.4 | 55 | |||||

Production

Conception

In December 1962, BBC Television's Controller of Programmes Donald Baverstock informed Head of Drama Sydney Newman of a gap in the schedule on Saturday evenings between the sports showcase Grandstand and the pop music programme Juke Box Jury. Baverstock figured that the programme should appeal to three audiences: children who had previously been accustomed to the timeslot, the teenage audience of Juke Box Jury, and the adult sports fan audience of Grandstand.[3] Newman decided that a science fiction programme should fill the gap.[4] Head of Serials Donald Wilson and writer C. E. Webber contributed heavily to the formatting of the programme, and co-wrote the programme's first format document with Newman;[5] the latter conceived the idea of a time machine larger on the inside than the outside, as well as the central character of the mysterious "Doctor", and the show's name Doctor Who.[6][b] Production was initiated several months later and handed to producer Verity Lambert and story editor David Whitaker to oversee, after a brief period when the show had been handled by a "caretaker" producer, Rex Tucker.[6]

Casting and characters

William Hartnell portrayed the first incarnation of the Doctor (referred to as "Dr. Who") in this season. The role was originally offered to Hugh David, Leslie French, Cyril Cusack, Alan Webb and Geoffrey Bayldon; David, Cusack and Webb turned down the role as they were reluctant to work on a series,[8][9] while Bayldon wished to avoid another "old man" role.[9] Lambert and director Waris Hussein invited William Hartnell to play the role; Hartnell accepted the role after several discussions, viewing it as an opportunity to take his career in a new direction.[10] Hartnell had always wished to play an older character in his work, but failed to do so, becoming typecast as a "tough" actor due to his roles in Carry On Sergeant (1958) and The Army Game (1957–61).[11] Although portrayed as grumpy and antagonistic in early episodes, the Doctor warms to his companions as the show progresses.[12]

The Doctor's granddaughter Susan Foreman was portrayed by Carole Ann Ford, a 23-year-old who typically played younger roles. Lambert was originally in talks with actress Jacqueline Lenya for the role,[13] and several actresses auditioned for the part, including Christa Bergmann, Anne Castaldini, Maureen Crombie, Heather Fleming, Camilla Hasse, Waveney Lee, Anna Palk and Anneke Wills.[14] Ford felt that the character of Susan deteriorated throughout the series; although the show's initial pitch depicted Susan as a strange alien creature, she often played the damsel in distress role, panicking at minor events.[15] Susan's school teachers Ian Chesterton and Barbara Wright were played by William Russell and Jacqueline Hill, respectively. Russell was the only actor considered by Lambert for the role of Chesterton.[16] While Sally Home, Phyllida Law and Penelope Lee were considered for Barbara,[14] Lambert chose Hill, her friend, for the role.[17]

Writing

Three particular story types were envisioned for the show: history of the past, technology in the future, and alternatives of the present.[15] Historical stories were intended to educate viewers about significant events in history, such as the Aztec civilisation and the French Revolution; futuristic episodes took a more subtle approach to educating viewers, such as the theme of pacifism in The Daleks.[18]

The programme was originally intended to open with a serial entitled The Giants, written by Webber,[19] but was scrapped by June 1963 as the technical requirements of the storyline—which involved the leading characters being drastically reduced in size—were beyond the technical capabilities, and the story itself lacked the necessary impact for an opener. Due to the lack of scripts ready for production, the untitled second serial from Coburn was moved to first in the running order.[20] The order change necessitated rewriting the opening episode of Coburn's script to include some introductory elements of Webber's script for the first episode of The Giants; as a result, Webber received a co-writer's credit for "An Unearthly Child" on internal BBC documentation.[21] Coburn also made several significant original contributions to the opening episode, most notably that the Doctor's time machine should resemble a police box, an idea he conceived after seeing a real police box while walking near his office.[21]

The second serial of Doctor Who was always planned to be futuristic due to the historical nature of the first. Comedy writer Terry Nation had written a 26-page outline for a story entitled The Survivors at his home, influenced by the threat of racial extermination by the Nazis and the concerns of advanced warfare, as well as taking influences from H. G. Wells' novel The Time Machine (1895).[22] Newman and Wilson were unhappy with the serial, having wanted to avoid featuring "bug-eyed monsters"; however, with no other scripts prepared, they were forced to accept the serial for production.[23] Due to other sudden commitments, Nation quickly wrote the scripts for the serial at the rate of one per day.[24] Nation also wrote the show's fifth serial, The Keys of Marinus, to replace Dr Who and the Hidden Planet by Malcolm Hulke, which was deemed problematic and required rewrites. Nation and Whitaker decided to base the serial around a series of "mini-adventures", each with a different setting and cast; Nation was intrigued by the idea of the TARDIS crew searching for parts of a puzzle.[25] Nation was also set to write the show's eighth serial, Doctor Who and the Red Fort, a seven-part story set during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, but other commitments prevented him from doing so.[26]

Newman suggested writer John Lucarotti to the production team during the show's early development. Lucarotti, who had recently worked on the 18-part radio serial The Three Journeys of Marco Polo (1955), penned a seven-part serial about the Italian merchant and explorer Marco Polo titled Dr Who and a Journey to Cathay.[27] Later known as Marco Polo, the serial was moved from its placement in the running order to accommodate The Edge of Destruction.[28] Lucarotti was approached to write The Aztecs while Marco Polo was in production. Having lived in Mexico, Lucarotti was fascinated by the Aztec civilisation[29] and their obsession with human sacrifice.[30] The show's eighth serial, The Reign of Terror, is also a historical story, though writer Dennis Spooner was initially interested in writing a science fiction story. Whitaker gave Spooner four possible historical subjects, and he ultimately selected the French Revolution.[31]

The show's third serial, The Edge of Destruction, was written as a "filler" in case the show was not renewed beyond 13 episodes. Since the serial had no budget and minimal resources, Whitaker took the opportunity to develop an idea conceived during the show's formative weeks: a character-driven story exploring the facets of the TARDIS.[32] He wrote the script in two days, drawing upon influences of ghost stories and haunted houses.[33] Peter R. Newman wrote the show's sixth serial, The Sensorites, inspired by 1950s films set during World War II that explore the notion of soldiers who continued to fight after the war.[34]

Filming

An Unearthly Child was provisionally scheduled to begin recording on 5 July,[35] but was delayed to 19 July.[36] Production was later deferred for a further two weeks while scripts were prepared.[37] The show's pilot recording was finally scheduled for 27 September and regular episodes made from 18 October.[38] Tucker was originally selected as the serial's director, but the task was assigned to Hussein following Tucker's departure from production.[21] Some of the pre-filmed inserts for the serial, shot at Ealing Studios in September and October 1963,[39] were directed by Hussein's production assistant Douglas Camfield.[40] The first version of the opening episode was recorded at Lime Grove Studios on the evening of 27 September 1963, following a week of rehearsals. However, the recording was bedevilled with technical errors, including the doors leading into the TARDIS control room failing to close properly. After viewing the episode, Newman ordered that it be mounted again. During the weeks between the two tapings, changes were made to costuming, effects, performances, and scripts.[41][c] The second attempt at the opening episode was recorded on 18 October, with the following three episodes being recorded weekly on 25 October, 1 November and 8 November.[21]

Tucker was initially appointed to direct The Daleks, but was later replaced by Christopher Barry.[43] A week of shooting for The Daleks took place from 28 October, consisting mostly of inserts of the city and models.[44] Weekly recording began on 15 November;[45] it was later discovered that the first recording was affected by induction—an effect in which the voices from the production assistants' headphones was clearly audible. The episode was re-recorded on 6 December, pushing the weekly recordings of episodes 4–7 back by one week.[46] The final episode was recorded on 10 January 1964.[44] The re-recording forced Paddy Russell to forego directing The Edge of Destruction due to other commitments; junior director Richard Martin was later handed the role,[47] and the first episode was recorded on 17 January.[48] Frank Cox directed the second episode on 24 January, as Martin was unavailable.[49] Filming for Marco Polo was preceded by a week of insert shooting of locations and props for the montage sequences.[50] The serial was recorded weekly from 31 January to 13 March, directed by Hussein;[50] John Crockett directed the fourth episode in Hussein's absence.[51]

Weekly recording for The Keys of Marinus, directed by John Gorrie, took place from 20 March to 24 April;[52] Hartnell was absent for the third and fourth episodes, as he was on holiday.[53] The Aztecs, directed by Crockett, was filmed from 1 to 22 May;[54] Ford appeared in pre-filmed inserts for the second and third episodes, shot on 13 April, due to her holiday.[55][56] Experienced director Mervyn Pinfield was chosen to direct the first four episodes of The Sensorites, while Frank Cox directed the final two episodes.[57] Recording took place from 29 March to 3 July;[58] Hill was absent for the fourth and fifth episodes due to her holiday.[59] The Reign of Terror featured the show's first outdoor filming in Denham, Buckinghamshire, led by cameraman Peter Hamilton on 15 June 1964.[60] Hungarian director Henric Hirsch directed the serial, which was recorded from 10 July to 19 August;[61] in preparation for his holiday, William Russell recorded inserts for the second and third episodes from 16–17 June.[62] Hirsch collapsed during the filming of the third episode. Lambert placed production assistant Tim Combe in charge until a replacement director could be found; documentation indicates that Gorrie oversaw production of the third episode,[63] though Gorrie has no memory of the event.[64] Hirsch returned to direct the final three episodes, splitting some of the workload with Combe.[61]

Release

Promotion

Doctor Who was announced by Control of BBC Television Stuart Hood on 12 September 1963, described by Television Mail as "a serial of stories to entertain the whole family". Trade newspaper Kinematograph Weekly devoted its TV column to the show on 24 October; journalist Tony Gruner described the show as "a somewhat mysterious type of programme consisting in part of fantasy and realism".[65] A trailer for the show was broadcast on the BBC on 16 November. The first serial was given a half-page preview in Radio Times on 21 November, outlining the show's main characters and upcoming settings.[66] On the same day, the main cast and production team attended the show's launch at Room 222 of the BBC's Broadcasting House. Hartnell hosted a radio trailer for the show on the BBC Light Programme.[67] The BBC Home Service programme Today hosted a one-minute piece about the show's "space music" on 22 November, and a second trailer for the show was screened on BBC in the evening.[68]

Hartnell taped a radio interview for Northern View on 17 December to promote the show's second serial. To increase the profile of the Daleks, the BBC sent two Dalek models—operated by Kevin Manser and Robert Jewell—to interact with the public at the Shepherd's Bush Market on 23 December. Hartnell recorded an appearance for Junior Points of View on 8 January, broadcast the following day, at Television Centre Presentation Studio A. In character as the Doctor, Hartnell spoke about the Daleks, based on dialogue written by Nation.[69] A promotional image of Marco Polo was featured on the cover of Radio Times on 20 February 1964, with a half-page introduction to the serial inside.[70] The Voord creatures from The Keys of Marinus were featured in several stories the Daily Express and Daily Mail in April 1964,[71] while the titular creatures from The Sensorites were featured in similar press pieces in June.[72] Lucarotti provided a syndicated interview with the press regarding The Aztecs, published in various papers such as the North-Western Evening Mail on 9 May.[73] On 20 June, Ford opened the East Ham Town Show at the Central Park in East Ham, with 20,000 people in attendance.[72] Radio Times ran a half-page interview with Hartnell on 16 July to promote the fourth episode of The Sensorites.[74]

Broadcast

The first episode of An Unearthly Child was transmitted on BBC TV at 5:16 p.m. on Saturday 23 November 1963; the following three episodes were transmitted at 5:15 p.m. over the next three weeks.[42] The serial has been repeated twice on the BBC: on BBC Two in November 1981 as part of the repeat season The Five Faces of Doctor Who,[42] and on BBC Four as part of the show's 50th anniversary on 21 November 2013.[75] The Daleks was broadcast across seven weeks from 21 December 1963 to 1 February 1964,[76] and has been repeated twice on the BBC: the final episode was broadcast on BBC Two late in the evening on 13 November 1999 as part of "Doctor Who Night"; and the serial was shown in three blocks from 5–9 April 2008 on BBC Four, as part of a celebration of the life and work of Lambert following her death in November 2007.[77] The Edge of Destruction was transmitted across two weeks, from 8 to 15 February 1964,[78] and Marco Polo was broadcast over seven weeks from 22 February to 4 April.[79] From the sixth episode of Marco Polo, the show's broadcast time was pushed a further fifteen minutes, from 5:15 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., overlapping with competitor programme ITV News.[80] Marco Polo was erased by the BBC on 17 August 1967; the entire serial is missing as a result.[79] It is one of three stories of which no footage whatsoever is known to have survived, though tele-snaps (images of the show during transmission, photographed from a television) of Episodes 1–3 and 5–7 exist,[81] and were subsequently released with the original audio soundtrack, which was recorded "off air" during the original transmission.[82]

The Keys of Marinus was transmitted across six weeks from 11 April to 16 May;[83] the third episode became the first Doctor Who episode to be transmitted on BBC1, following its renaming from BBC TV due to the launch of BBC2,[1] and the show's broadcast time returned to its original slot of 5:15 p.m. from the fifth episode.[1] The Aztecs was broadcast weekly from 23 May to 13 June.[84] The first two episodes of The Sensorites were broadcast on 20 and 27 June;[85] the second episode aired 25 minutes late due to an overrun of the previous programme Summer Grandstand.[86] While the third episode was provisionally scheduled to run two hours late on 4 July due to extended coverage of the Wimbledon tennis championships and Ashes Test match,[87] it was replaced by Juke Box Jury and postponed to the following week,[86] The final three episodes were broadcast weekly from 18 July to 1 August; Episodes 3–5 were erased by the BBC on 17 August 1967, while the remaining three were erased on 31 January 1969. BBC Enterprises retained negatives of the original 16 mm film with soundtracks made in 1967; these were returned to the BBC Archives in 1978.[85] The Reign of Terror was transmitted weekly from 8 August to 12 September;[88] the second and third episodes were shifted to the later time of 5:30 p.m., the fourth episode was broadcast at 5:15 p.m. (due to coverage of the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo),[89] and the final two episodes again shifted to 5:30 p.m.[88] The original prints of The Reign of Terror were wiped by BBC Enterprises in 1972. The sixth episode was returned to the BBC by a private collector in May 1982, and the first three episodes were located in Cyprus in late 1984; the fourth and fifth episodes remain missing, existing only as off-air recordings from 1964. The existing episodes were screened as part of the National Film Theatre's Bastille Day schedule on 14 July 1999, with links between the episodes by Ford.[88]

Home media

VHS releases

DVD and Blu-ray releases

All releases are for DVD unless otherwise indicated:

| Season | Story no. | Serial name | Number and duration of episodes |

R2 release date | R4 release date | R1 release date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–4 | An Unearthly Child The Daleks The Edge of Destruction Marco Polo (condensed reconstruction) |

13 × 25 min. 1 × 30 min. |

30 January 2006[90] | 2 March 2006[91] | 28 March 2006[92] |

| 2 | The Daleks in Colour | 1 × 75 min. 7 × 25 min. |

12 February 2024 (D,B) [93] | 4 September 2024 (D,B) [94] | 19 March 2024 (D,B) [95] | |

| 5 | The Keys of Marinus | 6 × 25 min. | 21 September 2009[96] | 7 January 2010[96] | 5 January 2010[97] | |

| 6 | The Aztecs | 4 × 25 min. | 21 October 2002[98] | 2 December 2002[98] | 4 March 2003[99] | |

| 6, 18 | The Aztecs (Special Edition) Galaxy 4[d] |

5 × 25 min. | 11 March 2013[98] | 20 March 2013[100] | 12 March 2013[101] | |

| 7 | The Sensorites | 6 × 25 min. | 23 January 2012[102] | 2 February 2012[102] | 14 February 2012[103] | |

| 8 | The Reign of Terror[e] | 6 × 25 min. | 28 January 2013[104] | 6 February 2013[105] | 12 February 2013[104] |

- ^ a b BBC TV was renamed BBC1 midway through the season, on 20 April 1964, following the launch of BBC2.[1]

- ^ Hugh David, an actor initially considered for the role of the Doctor and later a director on the programme, later claimed that Rex Tucker coined the title Doctor Who. Tucker claimed that it was Newman who had done so.[7]

- ^ The original episode, retroactively referred to as the "pilot episode", was not broadcast on television until 26 August 1991.[42]

- ^ Episode 3 of 4, condensed reconstruction of episodes 1, 2, and 4

- ^ Episodes 1–3 and 6 of 6, animation of 4 and 5

Books

| Serial name | Novelisation title | Author | First published |

|---|---|---|---|

| An Unearthly Child | Doctor Who and An Unearthly Child | Terrance Dicks | 15 October 1981[90] |

| The Daleks | Doctor Who in an Exciting Adventure with the Daleks | David Whitaker | 12 November 1964[106] |

| The Edge of Destruction | The Edge of Destruction | Nigel Robinson | 20 October 1988[107] |

| Marco Polo | Marco Polo | John Lucarotti | December 1984[108] |

| The Keys of Marinus | Doctor Who and the Keys of Marinus | Philip Hinchcliffe | 21 August 1980[109] |

| The Aztecs | The Aztecs | John Lucarotti | 21 June 1984[98] |

| The Sensorites | The Sensorites | Nigel Robinson | February 1987[110] |

| The Reign of Terror | The Reign of Terror | Ian Marter | March 1987[111] |

Reception

Ratings

The assassination of John F. Kennedy the day preceding the launch of Doctor Who overshadowed the first episode;[112] as a result, it was repeated a week later, on 30 November, preceding the second episode.[112] The first episode was watched by 4.4 million viewers (9.1% of the viewing audience), and it received a score of 63 on the Appreciation Index;[112] the repeat of the first episode reached a larger audience of six million viewers.[42] Across its four episodes, An Unearthly Child was watched by an average of 6 million (12.3% of potential viewers).[112] Mark Bould suggests that a disappointing audience reaction and high production costs prompted the BBC's chief of programmes to cancel the series until the Daleks, introduced in the second serial, were immediately popular with viewers.[113] The first two episodes of The Daleks received 6.9 and 6.4 million viewers, respectively. By the third episode, news about the Daleks had spread, and the episode was watched by 8.9 million viewers.[76] An additional million viewers watched for the following two weeks, and the final two episodes reached 10.4 million;[76] by the end of the serial, the show's overall audience had increased by 50%.[114] The following two serials retained these high viewing figures, with The Edge of Destruction receiving 10.4 and 9.9 million viewers,[78] and Marco Polo maintaining an average of 9.47 million viewers.[79]

The fourth episode of The Keys of Marinus received 10.4 million viewers, but saw a drop of 2.5 million viewers the following week, and an additional drop of one million for the sixth episode.[83] The drop in viewers for the sixth episode was attributed to the absence of Juke Box Jury, the programme that followed Doctor Who.[1] The Aztecs maintained these figures, with an average of 7.5 million viewers across the four episodes;[84] the third episode became the first episode of the show to place in the top 20 of the BBC's audience measurement charts.[115][a] The fourth and fifth episodes of The Sensorites dropped to 5.5 and 6.9 million viewers, respectively,[85] but were nonetheless the highest-rated BBC show in the BBC North region for their respective weeks.[86] The Reign of Terror received smaller audiences than previous serials due to the warmer weekends, with an average of around 6.7 million viewers, but still maintained a position within the top 40 shows for the week.[89]

Critical response

Doctor Who's first season received generally positive responses. For An Unearthly Child, Variety felt that the script "suffered from a glibness of characterisations which didn't carry the burden of belief", but praised the "effective camerawork", noting that the show "will impress if it decides to establish a firm base in realism". Mary Crozier of The Guardian was unimpressed by the first serial, stating that it "has fallen off badly soon after getting underway". Conversely, Marjorie Norris of Television Today commented that if the show "keeps up the high standard of the first two episodes it will capture a much wider audience".[117] The following serial, The Daleks, was widely praised, described by the Daily Mirror's Richard Sear as "splendid children's stuff". The serial's villains, the Daleks, became a cultural phenomenon, and have been closely associated with the show since.[114] The Edge of Destruction was criticised at a BBC Programme Review Board Meeting in February 1964 by controller of television programmes Stuart Hood, who felt that the serial's sequences in which Susan uses scissors as a weapon "digressed from the code of violence in programmes"; Lambert apologised for the scenes.[78]

Marco Polo was positively received; Philip Purser of The Sunday Telegraph noted that Mark Eden impersonated Marco Polo "with sartorial dash", but felt that the main characters were poorly written, describing Barbara as "a persistent drip".[118] The Keys of Marinus was criticised by Bob Leeson of the Daily Worker, who felt that the fifth episode of the serial was the show's low point, noting that the introduction of a trial scene represented a rushed script.[1] The following serial, The Aztecs, received high praise and is retrospectively seen as one of the show's greatest stories. Television Today's Bill Edmunds praised the serial's villains, but felt that Barbara should have "a chance to look beautiful instead of worried",[115] and Leeson of the Daily Worker felt that the serial had "charm", applauding the "painstaking attempts for historical accuracy" and noting a "much tighter plot" than previous serials.[119] The Reign of Terror was criticised for its historical inaccuracies, described by Daily Worker's Stewart Lane as a "half-baked royalist adventure".[120]

Retrospective reviews of the season are positive. Kimberley Piece of Geek Girl Authority felt that, while the season started slowly, it "managed to find its footing" and "developed quickly into a popular ratings favorite".[121] Simbasible found that most serials are memorable, though many feature repetitive and "silly" storytelling.[122] Richard Gray of The Reel Bits praised the imagination and perseverance of the show's producers.[123] Reviewing the first serial in 2008, Radio Times reviewer Patrick Mulkern praised the casting of Hartnell, the "moody" direction and the "thrilling" race back to the TARDIS.[124] For The Daleks, Mulkern praised the strength of Nation's scripts, particularly the first three cliffhangers, but felt that "the urgency and claustrophobia dissipate towards the end", describing the final battle as "a disappointingly limp affair".[125] Reviewing The Edge of Destruction, Mulkern described David Whitaker as "a master of dialogue, characterisation and atmosphere", but felt he struggled with plot logic, as evidenced by the fast return switch explanation.[126]

Mark Braxton of Radio Times praised Marco Polo, stating that "the historical landscape was rarely mapped with such poetry and elegance", though noted inconsistencies in the foreign characters' accents.[127] Mulkern wrote that "standards slip appreciably" in The Keys of Marinus,[128] and Arnold T. Blumberg of IGN described the serial as "a clichéd premise ... handled poorly and with no spark at all apart from Hartnell's late-hour rally".[129] Christopher Bahn of The A.V. Club described The Aztecs as "a classical tragedy infused with just enough hope toward the end to keep it from being unbearably bleak",[130] and Ian Berriman of SFX described the serial as "Jacqueline Hill's finest hour".[131] DVD Talk's John Sinnott considered The Sensorites "well constructed" with impressive set design and an expanded role for Susan, but felt that there was "nothing special" about the serial.[132] Mulkern wrote positively of the humour and Hartnell's increased role in The Reign of Terror, but felt that Susan was "at her weakest".[133]

References

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Ainsworth 2016, p. 119.

- ^ a b "Ratings Guide". Doctor Who News. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 3.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 166.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 182.

- ^ a b Molesworth, Richard (2006). Doctor Who: Origins. 2 Entertain.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 173.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, pp. 38–40.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2015, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Plomley, Roy; Hartnell, William (23 August 1965). Desert Island Discs (Radio broadcast). BBC Home Service. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 10.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 58.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2015, p. 48.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 57.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 59.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, pp. 181–2.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 186.

- ^ a b c d Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 123.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 120.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 96.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 48.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 49.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 134.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 135.

- ^ Wright 2016, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 18.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 27.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 49.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 220

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth 2015, p. 95.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 122.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2015, p. 151.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 139.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 65.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 115.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 108.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 146.

- ^ Howe, David J.; Walker, Stephen James (1998). "The Aztecs: Things to watch out for...". Doctor Who: The Television Companion. London: BBC Worldwide. p. 25. ISBN 0-563-40588-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 29.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 64.

- ^ a b Wright 2016, p. 76.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 65.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 72.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 86.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 87.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 88.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 153.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Wright 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 147.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 35.

- ^ "Doctor Who Guide: broadcasting for An Unearthly Child". The Doctor Who Guide. News in Time and Space. 2018. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2015, p. 159.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 78.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 76.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Chapman, Cliff (11 February 2014). "Doctor Who: the 10 stories you can't actually watch". Den of Geek. Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 120.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Wright 2016, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Wright 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Howe, Stammers & Walker 1994, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Wright 2016, p. 79.

- ^ a b Wright 2016, p. 78.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2015, p. 96.

- ^ "Doctor Who – The Beginning Box Set". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ Sinnott, John (1 April 2006). "Doctor Who: The Beginning". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Tantimedh, Adi (14 November 2023). "Doctor Who: "The Daleks" Remaster Coming to Blu-Ray/DVD – In Color". Bleeding Cool. Avatar Press. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Doctor Who: Daleks in Colour". Madman Entertainment. Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ "Doctor Who: The Daleks in Colour (Blu-ray)". BBC Shop. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Wallis, J. Doyle (25 February 2010). "Doctor Who: The Keys of Marinus". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth 2016, p. 151.

- ^ "Doctor Who – Story #006: The Aztecs DVD Information". TVShowsOnDVD.com. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Doctor Who The Aztecs Special Edition". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Doctor Who: The Aztecs Special Edition". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b Wright 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Sinnott, John (20 February 2012). "Doctor Who: The Sensorites". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ a b Wright 2016, p. 81.

- ^ "Doctor Who The Reign of Terror DVD". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 160.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 29.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 121.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Chapman 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Bould 2008, p. 215.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2015, p. 156.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 148.

- ^ Patrick, Seb (November 2013). "Best of 'Doctor Who' 50th Anniversary Poll: 11 Greatest Monsters & Villains". BBC America. BBC Worldwide. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Ainsworth 2015, p. 91.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 77.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Wright 2016, p. 123.

- ^ Pierce, Kimberly (19 May 2017). "Classic Doctor Who in Review: Season One". Geek Girl Authority. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "Doctor Who Season 1 Review". Simbasible. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Gray, Richard (13 September 2013). "'Doctor Who' 50th Anniversary Marathon Recap: Season 1 (1963 – 1964)". The Reel Bits. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (30 September 2008). "An Unearthly Child". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (1 October 2008). "The Daleks". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (2 October 2008). "The Edge of Destruction". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Braxton, Mark (3 October 2008). "Marco Polo". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (4 October 2008). "The Keys of Marinus". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Blumberg, Arnold T. (19 January 2010). "Doctor Who – The Keys of Marinus DVD Review". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Bahn, Christopher (25 September 2011). "Doctor Who (Classic): "The Aztecs"". The A.V. Club. Onion, Inc. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Berriman, Ian (8 March 2013). "Doctor Who: The Aztecs – Special Edition REVIEW". SFX. Future plc. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Sinnott, John (20 February 2012). "Doctor Who: The Sensorites". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (6 November 2008). "The Reign of Terror". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 8 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

Bibliography

- Ainsworth, John, ed. (2015). "100,000 BC and The Mutants (aka The Daleks)". Doctor Who: The Complete History. 1 (4). Panini Comics, Hachette Partworks.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ainsworth, John, ed. (2016). "Inside the Spaceship, Marco Polo, The Keys of Marinus and The Aztecs". Doctor Who: The Complete History. 2 (32). Panini Comics, Hachette Partworks.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bould, Mark (2008). "Science Fiction Television in the United Kingdom". In J.P. Telotte (ed.). The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2492-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chapman, James (2006). Inside the Tardis: The Worlds of Doctor Who. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-162-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Howe, David J.; Stammers, Mark; Walker, Stephen James (1994). Doctor Who The Handbook – The First Doctor. London: Doctor Who Books. ISBN 0-426-20430-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wright, Mark, ed. (2016). "The Sensorites, The Reign of Terror and Planet of Giants". Doctor Who: The Complete History. 3 (21). Panini Comics, Hachette Partworks.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)