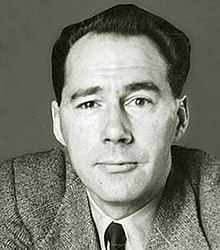

John Wyndham

John Wyndham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 July 1903 Dorridge, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 11 March 1969 (aged 65) Petersfield, Hampshire, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris[1] |

| Occupation | Science fiction writer |

John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris (/ˈwɪndəm/; 10 July 1903 – 11 March 1969)[2] was an English science fiction writer best known for his works published under the pen name John Wyndham, although he also used other combinations of his names, such as John Beynon and Lucas Parkes. Some of his works were set in post-apocalyptic landscapes. His best known works include The Day of the Triffids (1951) and The Midwich Cuckoos (1957), the latter filmed twice as Village of the Damned.

Early life

He was born in the village of Dorridge near Knowle, Warwickshire (now West Midlands), England, the son of George Beynon Harris, a barrister, and Gertrude Parkes, the daughter of a Birmingham ironmaster.[1]

His early childhood was spent in Edgbaston in Birmingham, but when he was 8 years old his parents separated. His father then attempted to sue the Parkes family for "the custody, control and society" of his wife and family, in an unusual and high-profile court case, which he lost. Following this embarrassment Gertrude left Birmingham to live in a series of boarding houses and spa hotels.[3] He and his younger brother, the writer Vivian Beynon Harris, spent the rest of their childhoods at a number of English preparatory and public schools, including Blundell's School in Tiverton, Devon, during the First World War. His longest and final stay was at Bedales School, near Petersfield in Hampshire (1918–21), which he left at the age of 18, and where he blossomed and was happy.

Early career

After leaving school Wyndham tried several careers, including farming, law, commercial art and advertising, but he mostly relied on an allowance from his family. He eventually turned to writing for money in 1925. In 1927 he published a detective novel, The Curse of the Burdens, as by John B. Harris, and by 1931 he was selling short stories and serial fiction to American science fiction magazines.[4] His debut short story, "Worlds to Barter", appeared under the pen name John B. Harris in 1931. Subsequent stories were credited to 'John Beynon Harris until mid-1935, when he began to use the pen name John Beynon. Three novels as by Beynon were published in 1935/36, two of them works of science fiction, the other a detective story. He also used the pen name Wyndham Parkes' for one short story in the British Fantasy Magazine in 1939, as John Beynon had already been credited for another story in the same issue.[5] During these years he lived at the Penn Club, London, which had been opened in 1920 by the remaining members of the Friends Ambulance Unit, and which had been partly funded by the Quakers. The intellectual and political mixture of pacifists, socialists and communists continued to inform his views on social engineering and feminism. At the Penn Club he met his future wife, Grace Wilson, a teacher. They embarked on a long-lasting love affair ,but did not marry, partly because of the marriage bar.[6]

The Second World War

During the Second World War Wyndham first served as a censor in the Ministry of Information.[7] He drew on his experiences as a firewatcher during the London Blitz, and later as a member of the Home Guard, in The Day of the Triffids.

He then joined the British Army, serving as a corporal cipher operator in the Royal Corps of Signals.[8] He participated in the Normandy landings, landing a few days after D-Day.[1] He was attached to the XXX Corps, which took part in some of the heaviest fighting, including surrounding the trapped German army in the Falaise Pocket.

His wartime letters to his long-time partner Grace Wilson are now held in the Archoves of the University of Liverpool.[9] He wrote at length of his struggles with his conscience, his doubts about humanity and his fears of the inevitability of further war. He also wrote passionately about his love for her and his fears that he would be so tainted she would not be able to love him when he returned.[10]

Postwar

After the war Wyndham returned to writing, still using the pen name John Beynon. Inspired by the success of his younger brother Vivian Beynon Harris, who had four novels published starting in 1948, he altered his writing style and, by 1951, using the pen name John Wyndham pen name for the first time, he wrote the novel The Day of the Triffids. His pre-war writing career was not mentioned in the book's publicity and people were allowed to assume that this was a first novel from a previously unknown writer.[4] The book had an enormous success[7] and established Wyndham as an important exponent of science fiction. During his lifetime he wrote and published six more novels under the name John Wyndham, and used that name professionally from 1951 onwardx. His novel The Outward Urge (1959 ) was credited to John Wyndham and Lucas Parkes, but Lucas Parkes was yet another pseudonym for Wyndham himself. Two story collections were published in the 1950s came out under Wyndham's name, but included several stories originally published as by John Beynon before 1951.

Personal life

In 1963 he married Grace Isobel Wilson, whom he had known for more than 20 years by then. The couple remained married until he died. They lived for several years in separate rooms at the Penn Club, London, but later lived near Petersfield, Hampshire, just outside the grounds of Bedales School. Wyndham explores the issues facing women forced by their biology to choose between careers and love in Trouble with Lichen.

Death and Posthumous Events

He died in 1969, aged 65, at his home in Petersfield. He was survived by his wife and his brother.[11]

Subsequently some of his unsold work was published and his earlier work was republished. His archive was acquired by Liverpool University.[12]

On 24 May 2015 an alley in Hampstead that appears in The Day of the Triffids was formally named Triffid Alley as a memorial to him.[13]

Books

Early novels published under other pen names

- The Curse of the Burdens (1927), as by John B. Harris: Aldine Mystery Novels No. 17 (London: Aldine Publishing Co. Ltd)

- The Secret People (1935), as by John Beynon

- Foul Play Suspected (1935), as by John Beynon

- Planet Plane (1936), as by John Beynon; republished as The Space Machine and as Stowaway to Mars

Novels published in his lifetime as by John Wyndham

- The Day of the Triffids (1951), also known as Revolt of the Triffids

- The Kraken Wakes (1953), published in the U.S. as Out of the Deeps

- The Chrysalids (1955), published in the U.S. as Re-Birth

- The Midwich Cuckoos (1957), filmed twice as Village of the Damned

- The Outward Urge (1959), as by John Wyndham and Lucas Parkes

- Trouble with Lichen (1960)

- Chocky (1968)

Posthumously published novels

- Web (1979)

- Plan for Chaos (2009)

Short story collections published in his lifetime

- Jizzle (1954) ("Jizzle", "Technical Slip", "A Present from Brunswick", "Chinese Puzzle", "Esmeralda", "How Do I Do?", "Una", "Affair of the Heart", "Confidence Trick", "The Wheel", "Look Natural, Please!", "Perforce to Dream", "Reservation Deferred", "Heaven Scent", "More Spinned Against")

- The Seeds of Time (1956) ("Chronoclasm", "Time to Rest", "Meteor", "Survival", "Pawley's Peepholes", "Opposite Number", "Pillar to Post", "Dumb Martian", "Compassion Circuit", "Wild Flower")

- Tales of Gooseflesh and Laughter (1956), U.S. edition featuring stories from the two earlier collections

- Consider Her Ways and Others (1961) ("Consider Her Ways", "Odd", "Oh, Where, Now, is Peggy MacRaffery?", "Stitch in Time", "Random Quest", "A Long Spoon")

- The Infinite Moment (1961), U.S. edition of Consider Her Ways and Others, with two stories dropped, two others added

Posthumously published collections

- Sleepers of Mars (1973), a collection of five stories originally published in magazines in the 1930s: "Sleepers of Mars", "Worlds to Barter", "Invisible Monster", "The Man from Earth" and "The Third Vibrator"

- The Best of John Wyndham (1973)

- Wanderers of Time (1973), a collection of five stories originally published in magazines in the 1930s: "Wanderers of Time", "Derelict of Space", "Child of Power", "The Last Lunarians" and "The Puff-ball Menace" (aka "Spheres of Hell")

- Exiles on Asperus (1979)

- No Place Like Earth (2003)

Short stories

John Wyndham's many short stories have also appeared with later variant titles or pen names. The stories include:

- "Worlds to Barter" (1931)

- "The Lost Machine" (1932)

- "The Stare" (1932)

- "The Venus Adventure" (1932)

- "Exiles on Asperus" (1933)

- "Invisible Monster" (1933)

- "Spheres of Hell" (1933) [as by John Beynon]

- "The Third Vibrator" (1933)

- "Wanderers of Time" (1933) [as by John Beynon]

- "The Man from Earth" (1934)

- "The Last Lunarians" (1934) [as by John Beynon]

- "The Moon Devils" (1934) [as by John Beynon Harris]

- "The Cathedral Crypt" (1935) [as by John Beynon Harris]

- "The Perfect Creature" (1937)

- "Judson's Annihilator" (1938) [as by John Beynon]

- "Child of Power" (1939) [as by John Beynon]

- "Derelict of Space" (1939) [as by John Beynon]

- "The Trojan Beam" (1939)

- "Vengeance by Proxy" (1940) [as by John Beynon]

- "Meteor" (1941) [as by John Beynon]

- "Living Lies" (1946) [as by John Beynon]

- "Technical Slip" (1949) [as by John Beynon]

- "Jizzle" (1949)

- "Adaptation" (1949) [as by John Beynon]

- "The Eternal Eye" (1950)

- "Pawley's Peepholes" (1951)

- "The Red Stuff" (1951)

- "Tyrant and Slave-Girl on Planet Venus" (1951) [as by John Beynon]

- "And the Walls Came Tumbling Down" (1951)

- "A Present from Brunswick" (1951)

- "Bargain from Brunswick" (1951)

- "Pillar to Post" (1951)

- "The Wheel" (1952)

- "Survival" (1952)

- "Dumb Martian" (1952)

- "Time Out" (1953)

- "Close Behind Him" (1953)

- "Time Stops Today" (1953)

- "Chinese Puzzle" (1953)

- "Chronoclasm' (1953)

- "Reservation Deferred' (1953)

- "More Spinned Against" (1953)

- "Confidence Trick' (1953)

- "How Do I Do?" (1953)

- "Esmeralda" (1954)

- "Heaven Scent" (1954)

- "Look Natural, Please!" (1954)

- "Never on Mars" (1954)

- "Perforce to Dream" (1954)

- "Opposite Numbers" (1954)

- "Compassion Circuit" (1954)

- "Wild Flower" (1955)

- "Consider Her Ways" (1956)

- "The Day of the Triffids" (1957) [an excerpt from the novel]

- "But a Kind of Ghost" (1957)

- "The Meddler" (1958)

- "A Long Spoon" (1960)

- "Odd" (1961)

- "Oh, Where, Now, Is Peggy MacRafferty?" (1961)

- "Random Quest" (1961)

- "Stitch in Time" (1961)

- "It's a Wise Child" (1962)

- "Chocky" (1963)

- "From The Day of the Triffids" (1964)

- "In Outer Space There Shone a Star" (1965)

- "A Life Postponed" (1968)

- "Phase Two" (1973) [an excerpt]

- "Vivisection" (2000) [as by J. W. B. Harris]

- "Blackmoil" (2003)

- "The Midwich Cuckoos" (2005) [with Pauline Francis]

Critical reception

John Wyndham's reputation rests mainly on the first four of the novels published in his lifetime under that name.[a] The Day of the Triffids remains his best-known work, but some readers consider that The Chrysalids was really his best.[14][15][16] This is set in the far future of a post-nuclear dystopia where women's fertility is compromised and they are severely oppressed if they give birth to "mutants". David Mitchell, author of Cloud Atlas, wrote of it: ""One of the most thoughtful post-apocalypse novels ever written. Wyndham was a true English visionary, a William Blake with a science doctorate."[17]

The ideas in The Chrysalids are echoed in The Handmaid's Tale, whose author, Margaret Atwood, has acknowledged Wyndham's work as an influence. She wrote an introduction to a new edition of Chocky in which she states that the intelligent alien babies in The Midwich Cuckoos entered her dreams.[18]

Wyndham also wrote several short stories, ranging from hard science fiction to whimsical fantasy. A few have been filmed: Consider Her Ways, Random Quest, Dumb Martian, A Long Spoon, Jizzle (filmed as Maria) and Time to Rest (filmed as No Place Like Earth).[19] There is also a radio version of Survival.

Brian Aldiss, another British science fiction writer, disparagingly labelled some of Wyndham's novels as "cosy catastrophes", especially The Day of the Triffids,.[20] This became a cliche about his work, but it has been refuted by many more recent critics. L.J. Hurst pointed out that in Triffids the main character witnesses several murders, suicides and misadventures, and is frequently in mortal danger himself.[21] Margaret Atwood wrote: "one might as well call World War II—of which Wyndham was a veteran—a "cozy" war because not everyone died in it."[18]

Many other writers have acknowledged Wyndham's work as an influence on theirs, including Alex Garland, whose screenplay for 28 Days Later draws heavily on The Day of the Triffids.[22]

References

Notes

- ^ For example, around 2000 they were all reprinted as Penguin Modern Classics.

Citations

- ^ a b c Aldiss, Brian W. "Harris, John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Online birth records show that the birth of a John Wyndham P. L. B. Harris was registered in Solihull in July–September 1903.

- ^ Binns, Amy (2019). Hidden Wyndham: Life, Love, Letters. London: Grace Judson Press. pp. 30–32. ISBN 9780992756710.

- ^ a b "John Wyndham & H G Wells". Christopher Priest. 1 December 2000. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Summary Bibliography: John Wyndham". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Binns, Amy. HIDDEN WYNDHAM : life, love, letters. GRACE JUDSON PRESS. pp. 65–77. ISBN 9780992756710.

- ^ a b Liptak, Andrew (7 May 2015). "John Wyndham and the Global Expansion of Science Fiction". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "John Wyndham". The Guardian. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "John Wyndham Archive". University of Liverpool Special Collection Archive.

- ^ Binns, Amy. HIDDEN WYNDHAM : life, love, letters. GRACE JUDSON PRESS. ISBN 9780992756710.

- ^ "John Wyndham". Literary Encyclopedia. 7 November 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "John Wyndham Archive". Liv.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Triffid Alley, Hampstead". Triffid Alley. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "The Chrysalids – Novel". h2g2. BBC. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Aldiss 1973, p. 254.

- ^ "Jo Walton's review of The Chrysalids".

- ^ "The Chrysalids by John Wyndham: 9781590172926 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ a b Atwood, Margaret (8 September 2015). "The Forgotten Sci-Fi Classic That Reads Like a Prequel to E.T." Slate Magazine. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ IMDb

- ^ Aldiss 1973, p. 293.

- ^ Hurst, L. J. (August–September 1986), ""We Are The Dead": The Day of the Triffids and Nineteen Eighty-Four", Vector, 113, Pipex: 4–5, archived from the original on 10 August 2013

- ^ Kaye, Don (28 April 2015). "Exclusive: Ex Machina writer/director Alex Garland on 'small' sci-fi films, sentient machines and going mainstream". SYFY WIRE.

Bibliography

- Aldiss, Brian W (1973), Billion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-76555-4

- Harris, Vivian Beynon, "My Brother, John Wyndham: A Memoir" transcribed and edited by David Ketterer, in Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction 28 (Spring 1999) pp. 5–50

- Binns, Amy (2019), HIDDEN WYNDHAM : life, love, letters., GRACE JUDSON PRESS, ISBN 9780992756710

- Ketterer David, "Questions and Answers: The Life and Fiction of John Wyndham" in The New York Review of Science Fiction 16 (March 2004) pp. 1, 6–10

- Ketterer, David, "The Genesis of the Triffids" in The New York Review of Science Fiction 16 (March 2004) pp. 11–14

- Ketterer, David, "John Wyndham and the Sins of His Father: Damaging Disclosures in Court" in Extrapolation 46 (Summer 2005) pp. 163–188

- Ketterer, David, "'Vivisection': Schoolboy John Wyndham's First Publication?" in Science Fiction Studies 78 (July 1999): pp. 303–311, expanded and corrected in Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction 29 (Summer 2000) pp. 70–84

- Ketterer, David, "'A Part of the . . . Family': John Wyndham's *The Midwich Cuckoos* as Estranged Autobiography" in Learning from Other Worlds: Estrangement, Cognition and the Politics of Science Fiction and Utopia edited by Patrick Parrinder (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2001) pp. 146–177

- Ketterer, David, "When and Where Was John Wyndham Born?" in Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction 42 (Summer 2012/13) pp. 22–39

- Ketterer, David, "John Wyndham (1903[?]–1969)" in The Literary Encyclopedia (online, 7 November 2006)

- Ketterer, David, "John Wyndham: The Facts of Life Sextet" in A Companion to Science Fiction edited by David Seed (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003) pp. 375–388

- Ketterer, David, "John Wyndham's World War III and His Abandoned Fury of Creation Trilogy" in Future Wars: The Anticipations and the Fears edited by David Seed (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012) pp. 103–129

- Ketterer, David, "John B. Harris's Mars Rover on Earth" in Science Fiction Studies 41 (July 2014) pp. 474–475

External links

- Works by John Wyndham at Faded Page (Canada)

- The John Wyndham Archive, The University of Liverpool, archived from the original on 11 September 2017, retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "John Wyndham", The Guardian (article), London, 22 July 2008, archived from the original on 11 November 2004, retrieved 10 November 2004.

- Priest, Christopher, Portrait of Wyndham and Wells, UK: Tiscali

- Ketterer, "'Vivisection': Schoolboy 'John Wyndham's' First Publication?", SFS, 78, Depauw, archived from the original on 8 January 2004, retrieved 19 December 2003.

- John Wyndham (Realplayer) (TV interview), UK: BBC, 1960[dead link]

- John Wyndham on the Nature of Evil in His Novels (interview), On writers, UK: BBC, 1960 (somehow restricted to viewing only in UK)

- John Wyndham at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "John Wyndham first editions", Book seller world (bibliography), archived from the original on 25 February 2006, retrieved 5 February 2006.

- Wyndham Web: The Internet's First Dedicated John Wyndham Site, archived from the original on 13 August 2017, retrieved 25 June 2020.

- 1903 births

- 1969 deaths

- People educated at Blundell's School

- People educated at Bedales School

- English short story writers

- English horror writers

- English science fiction writers

- People from Birmingham, West Midlands

- People from Petersfield

- Royal Corps of Signals soldiers

- British Army personnel of World War II

- Pseudonymous writers

- People educated at Shardlow Hall

- 20th-century English novelists

- English male novelists

- 20th-century British male writers

- English male non-fiction writers