Eureka Flag

The Eureka Flag is the war flag flown at the battle of the Eureka Stockade that took place on 3 December 1854 at Ballarat in Victoria, Australia. An estimated crowd of over 10,000 people swore allegiance to the flag as a symbol of defiance at Bakery Hill on 29 November 1854.[1] Over 30 miners were killed at the Eureka Stockade, along with six troopers and police. Some 125 miners were arrested and many others badly wounded.[2]

The field is Prussian blue measuring 260 cm × 400 cm (2:3.08 ratio) and made from fine woollen fabric. The horizontal cross is 37 cm wide and the vertical cross 36 cm wide. The central star is slightly larger (8.5%) than the others being 65 cm tall from point to point and the other stars 60 cm. The white stars are made from fine cotton lawn and the off-white cross from cotton twill.[3]

It is listed as an object of significance on the Victorian Heritage Register[4] and was designated as a Victorian icon by the National Trust in 2006.[5]

History

Origin and symbolism

According to one popular tradition the flag design is credited to a Canadian member of the Ballarat Reform League, 'Captain' Henry Ross of Toronto. In 1885, John Wilson, who was employed by the Victorian Works Department at Ballarat as a foreman, made the claim that he had originally conceptualised the Eureka flag after becoming sympathetic to the rebel cause. He then recalls that it was constructed from bunting by a tarpaulin maker.[6][7] A. W. Crowe recounted in 1893 that "it was Ross who gave the order for the insurgents' flag at Darton and Walker's."[8] Crowe's story is confirmed in as far as there were advertisements that appeared in the Ballarat Times dating from October–November 1854 for Darton and Walker, manufacturers of tents, tarpaulin and flags, situated at the Gravel Pits. There is also another legend where the flag was sewn by three local women - Anastasia Withers, Anne Duke and Anastasia Hayes.[2] The stars are made of a delicate material which is consistent with the story they were made out of their petticoats[9] and the "blue woollen material certainly bears a marked resemblance to the standard dressmaker's length of material for making up one of the voluminous dresses of the 1850s."[10] The earliest mention of a flag was the report of a meeting held on 23 October 1854 to discuss indemnifying Andrew McIntyre and Thomas Fletcher who had both been arrested. The article published in The Herald, 7 November 1854 edition, also states that: "Mr. Kennedy suggested that a tall flag pole should be erected on some conspicuous site, the hoisting of the diggers' flag on which should be the signal for calling toge-ther a meeting on any subject which might require immediate consideration."[11]

Frank Cayley in his seminal Flag of Stars claims to have found two sketches on a visit to the soon-to-be headquarters of the Ballarat Historical Society in 1963, which may be the original plans for the Eureka flag. One is a two dimensional drawing of the Eureka flag inscribed with the words "blue" and "white" to denote the colour scheme and Cayley has concluded: "It looks like a rough design of the so-called King Flag."[12] The other sketch was "pasted on the same piece of card shows the flag being carried by a bearded man" that Cayley believes may have been intended as a representation of Henry Ross.[13]

There has been an expert analysis of the Cayley sketches carried out by Ballarat militaria consultant Paul O'Brien who says:

"This sketch, once in the collection of the Ballarat Historical Society, location now unknown, was originally displayed with another sketch representing the 'Eureka' or 'King' flag and was labelled 'Found in a Tent After the Affair at Eureka'. The sketches were first reproduced in Frank Cayley's book Flag of Stars (Rigby, 1966). The assumption made in the accompanying text was that the sketch was a draft design for the making of the flag.

"While this assumption is quite plausible, it would seem more likely that the sketch was made after the capture of the flag. Note the tattered leading edge and indistinct star. The number of points to the stars represented also does not tally with those on the surviving 'King' flag. This sketch was, perhaps, drawn after the flag was 'brought in triumph' to the government camp and while it was being savaged by eager souvenir hunters.

"The two sketches have been drawn by different hands, and many details of design differ considerably (notably the hoist edge and number of star points). The size of the flag in the sketch with figure does not tally with the enormous size of the 'King' flag, and is probably a later, not contemporary, representation."[14]

Professor Anne Beggs-Sunter mentions an article reportedly published in the Ballarat Times "shortly after the Stockade referring to two women making the flag from an original drawing by a digger named Ross. Unfortunately no complete set of the Ballarat Times exists, and it is impossible to locate this intriguing reference."[10][15]

The theory that the Eureka flag is based on the Australian Federation Flag has precedents in that "borrowing the general flag design of the country one is revolting against can be found in many instances of colonial liberation, including Haiti, Venezuela, Iceland, and Guinea."[16][17] There is also a strong resemblance with the Flag of Quebec, where Ross was born. Another possible influence is the blue and white flag featuring a couped cross that flew at the tent where St Alipius chapel was located.[18] Professor Geoffrey Blainey believes that the white cross on which the stars of the Eureka flag are arrayed is "really an Irish cross rather than being [a] configuration of the Southern Cross."[19]

Cayley has stated that the field "may have been inspired by the sky, but was more probably intended to match the blue shirts worn by the diggers."[20][21] The number of points on the stars appears to have been a mere convenience as eight would be the easiest to manufacture in the absence of specialised sewing instruments.[3]

Oath swearing at Bakery Hill

The flag raising ceremony on 29 November 1854 where the oath was sworn at Bakery Hill was not the first flying of the Eureka flag that day. In his open letter to the colonists of Victoria, dated 7 April 1855, Peter Lalor said that upon hearing news of the fracas at the Eureka gold reef involving the military reinforcements that had just arrived, he headed towards Barker and Hunt's store on Specimen Hill where, "The 'Southern Cross' was procured and hoisted on the flagstaff belonging to Barker and Hunt; but it was almost immediately hauled down, and we moved down to the holes on the Gravel Pits Flat."[22]

In his memoirs John Wilson recalled enlisting the help of prisoners to procure the flag pole on Bakery Hill that was 60 ft long and felled from an area known as Byle's Swamp in Bullarook Forest.[23] It was then set into an abandoned mineshaft and his design of "five white stars on a blue ground, floated gaily in the breeze."[24]

The Ballarat Times first mentioned the Eureka flag on 24 November 1854 in an article about a meeting of the Ballarat Reform League to be held the following Wednesday where "the Australian flag shall triumphantly wave, a symbol of Liberty." There are also other examples of the Eureka flag being referred to at the time as the Australian flag. It was reported in The Age, 28 November 1854 edition, that: "The Australian flag shall triumphantly wave in the sunshine of its own blue and peerless sky, over thousands of Australia's adopted sons."[25] The day after the battle their readers were told: "They assembled round the Australian flag, which has now a permanent flag-staff."[26] In a despatch Governor Charles Hotham said: "The disaffected miners ... held a meeting whereat the Australian flag of independence was solemnly consecrated and vows offered for its defence."[27]

In the subsequent Ballarat Times report of the oath swearing ceremony it was stated that:

"During the whole of the morning several men were busily employed in erecting a stage and planting the flagstaff. This is a splendid pole of about 80 feet and straight as an arrow. This work being completed about 11 o'clock, the Southern Cross was hoisted, and its maiden appearance was a fascinating object to behold. There is no flag in Europe, or in the civilised world, half so beautiful and Bakery Hill as being the first place where the Australian ensign was first hoisted, will be recorded in the deathless and indelible pages of history. The flag is silk, blue ground with a large silver cross; no device or arms, but all exceedingly chaste and natural."[28]

Near the base of the flagpole Lalor their elected leader knelt down with his head uncovered, pointed his right hand to the Eureka flag, and swore to the affirmation of his fellow demonstrators: "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties."[29] Raffaello Carboni's account of the oath swearing ceremony states that Ross was the "bridegroom" of the Eureka flag and "sword in hand, he had posted himself at the foot of the flag-staff, surrounded by his rifle division."[30]

In 1932, R. S. Reed claimed that "an old tree stump on the south side of Victoria Street, near Humffray Street, is the historic tree at which the pioneer diggers gathered in the days before the Eureka Stockade, to discuss their grievances against the officialdom of the time."[31] Reed called for the formation of a committee of citizens to "beautify the spot, and to preserve the tree stump" upon which Lalor addressed the assembled rebels during the oath swearing ceremony.[32] It was also reported the stump "has been securely fenced in, and the enclosed area is to be planted with floriferous trees. The spot is adjacent to Eureka, which is famed alike for the stockade fight and for the fact that the Welcome Nugget. (sold for £10,500) was discovered in 1858 within a stone's throw of it."[33]

The modern day address of the oath swearing ceremony is likely to be 29 St. Paul's Way, Bakery Hill.[34] Although it is presently a carpark and for a hundred years was the location of a school, it will soon be the location of an apartment block.[35]

Seized by police at Eureka Stockade

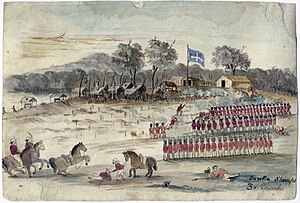

After the oath swearing ceremony the rebels marched in double file behind the Eureka flag from Bakery Hill to the Eureka gold reef where construction of the stockade began.[36][37] In his 1855 memoirs Raffaello Carboni again mentions the role of Henry Ross who "was our standard-bearer. He hoisted down the Southern Cross from the flag-staff, and headed the march."[38]

In his report dated 14 December 1854, Captain John Thomas mentioned: "the fact of the Flag belonging to the Insurgents (which had been nailed to the flagstaff) being captured by Constable King of the Force."[39] John King, who had voluteered for the honour while the battle was still raging, had to scale the flag pole which then snapped and he fell to the ground.[40] Carboni who was an eyewitness to the battle recalls that: "A wild 'hurrah!' burst out and 'the Southern Cross' was torn down, I should say, among their laughter, such as if it had been a prize from a May-pole."[41] The Geelong Advertiser reported that the Eureka flag "was carried by in triumph to the Camp, waved about in the air, then pitched from one to another, thrown down and trampled on."[42] The soldiers also danced around the Eureka flag on a pole that was "now a sadly tattered flag from which souvenir hunters had cut and torn pieces."[43][44] The morning after the battle "the policeman who captured the flag exhibited it to the curious and allowed such as so desired to tear off small portions of its ragged end to preserve as souvenirs."[45]

Exhibit in High Treason trials

At the Eureka state treason trials that began on 22 February 1855, the 13 defendants had it put to them that they did "traitorously assemble together against our Lady the Queen" and attempt "by the force of arms to destroy the Government constituted there and by law established, and to depose our Lady the Queen from the kingly name and her Imperial Crown."[46] Furthermore, in the relation to the "overt acts" that constituted the actus reus of the offence, the indictment read: "That you raised upon a pole, and collected round a certain standard, and did solemnly swear to defend each other, with the intention of levying war against our said Lady the Queen."[46]

Called as a witness in the state treason trials, during examination in chief assistant civil commissary and magistrate, George Webster, testified that upon entering the stockade the besieging forces "immediately made towards the flag, and the flag was pulled down by the police."[47] John King testified that: "[he] took their flag, the Southern Cross, down - the same flag as now produced."[48]

In his closing submission the defence counsel Henry Chapman argued there were no inferences to be drawn from the hoisting of the Eureka flag, saying:

"and if the fact of hoisting that flag be at all relied upon as evidence of an intention to depose Her Majesty ... no inference whatever can be drawn from the mere hoisting of a flag as to the intention of the parties, because of the witnesses has said that two hundred flags were hoisted at the diggings; and if two hundred persons on the same spot choose to hoist their particular flag, what each means we are utterly unable to tell, and no general meaning as to hostility to the Government can be drawn from the simple fact that the diggers on that occasion hoisted a flag ... I only throw it out to you because it is utterly impossible, in the multiplicity of flags that have been hoisted on the diggings, to draw an exact inference as to the hoisting of any one particular flag at one spot."[49]

Post-battle preservation

The Eureka flag was retained by John King who quit the police force two days after the state treason trials ended to become a farmer. In the late 1870s he eventually settled near Minyip in the Victorian Wimmera district. It was here the Eureka flag "made occasional appearances at country bazaars."[10] In his 1870 history of Ballarat, William Withers said he had not been able to find out what had happened to the Eureka flag.[50] Professor Anne Beggs-Sunter thinks it is "likely that King read Withers's book, because he wrote to the Melbourne Public Library offering to sell the flag to that institution."[10] The head librarian, Marcus Clarke, approached Peter Lalor to authenticate the flag but he was unable asking, "Can you find someone whose memory is more accurate than mine?"[51] The library eventually decided not to acquire the flag due to the uncertainty over its origins. It would remain in the custody of the King family for forty years until 1895 when it was lent to the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery (now the Art Gallery of Ballarat). John King's widow Isabella would post the Eureka flag after being approached by gallery president, James Oddie, along with a letter to the secretary which reads:

Kingsley, Minyip,

1st October, 1895

Dear Sir, In connection with the wish of the president of the Ballarat Fine Arts and Public Gallery for the gift or loan of the flag that floated above the Eureka Stockade, I have much pleasure in offering loan of flag to the above association on condition that I may get it at any time I specify, or on demand of myself or my son, Arthur King. The main portion of the flag was torn along the rope that attached it to the staff, but there is still part of it around the rope so that I suppose it would be best to send the whole of it as it now is. You will find several holes, that were caused by bullets that were fired at my late husband in his endeavours to seize the flag at that memorable event:- Yours, &c.,

Mrs J. King (per Arthur King)[52]

It remained at the gallery in continued obscurity "under a cloud of skepticism and conservative disapproval"; bits of the flag were cut off and given to visiting dignitaries.[53] Approximately 31% of the original specimen is missing. The flag was "re-discovered" by Len Fox during the 1940s,[54] but it took decades to convince authorities to properly authenticate the flag.[citation needed] It was found after World War II in a drawer at the gallery, discovered by members of the Australian Communist Party.[53] The final irrefutable validation of its authentication occurred when sketchbooks of Canadian Charles Doudiet were put up for sale at a Christies auction in 1996. Two sketches in particular show the flag design as being the same as the tattered remains of the original specimen that was first put on public display at the Art Gallery of Ballarat in 1973, at a ceremony attended by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.[55] The gallery had received a $1,000 grant from the state government to cover half the estimated cost of repairing and mounting the Eureka flag.[56]

In 2001, legal ownership of the flag was transferred to the Art Gallery of Ballarat. There was a second extensive restoration of the Eureka flag undertaken in 2011 by leading textile conservation specialists Artlab Australia. The City of Ballarat had received a permit from heritage Victoria to proceed with the conservation work, and a full assessment of the state of the flag was commissioned. The report complied by Artlab described the Eureka Flag as "arguably the most important historical textile in Australia." The old backing cloth was replaced with state of the art materials that are less prone to deterioration, as was the timber backing board and a new, purpose-built, low light, temperature controlled display case was constructed.[57][58] The flag was then loaned to the Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka (MADE) by the gallery in 2013. When MADE closed in 2018, the interpretive centre came under the management of the City of Ballarat. The premises were opened once again to the public in April 2018, with the flag retained as the centrepiece of a visitor experience now branded as the Eureka Centre Ballarat, while remaining part of the gallery collection.[59]

Customary use

Since the original miners revolt at Eureka, the flag, born out of adversity, has gained wider notability in Australian culture as a symbol of democracy, egalitarianism, and general purpose symbol of protest,[60][61] mainly in relation to a variety of anti-establishment, non-conformist causes.[62] Whilst some Australians view the Eureka Flag as a symbol of nationality[63] (see Australian flag debate), it has more often been employed by historical societies and re-enactors and militant left-wing trade unions such as the former Builders Labourers Federation. More recently it has been adopted by right-wing organizations and political parties, including the Australia First Party, National Action and some neo-Nazi groups,[64] much to the frustration of more established socialist and progressive claimants. Depending on their political persuasion, these groups either see it as representative of the miner's efforts to free themselves from political or economic oppression, or their sentiments in favour of restricting non-white immigration and the eventual Chinese poll tax.

In a 2013 survey where respondents were asked about national symbols McCrindle Research found the Eureka flag eliciting a "mixed response with 1 in 10 (10%) being extremely proud while 1 in 3 (35%) are uncomfortable with its use."[65]

Post Eureka

There is an oral tradition that Eureka flags were on display at a seaman's union protest against the use of cheap Asian labour on ships at Circular Quay in 1878.[66] In August 1890 a crowd of 30,000 protesters gathered at the Yarra Bank in Melbourne under a platform draped with the Eureka flag in a show of solidarity with maritime workers.[67] A similar flag was flown prominently above the camp at Barcaldine during the 1891 Australian shearers' strike.[68]

In 1948 a procession of 3,000 members of the Communist affiliated Eureka Youth League and allied unionists led by a Eureka flag bearer marched through the streets of Melbourne on the occasion of the 94th anniversary of the Eureka Stockade.[69] The same year there were headlines in the Argus newspaper stating "Police in serious clash with strikers" and "Battle over Eureka flag" arising from a violent clash between about 500 strikers and police during a procession on St Patrick's Day in Brisbane. The marchers were singing "It's a Great Day for the Irish" and "Advance, Australia Fair" whilst carrying shamrock shaped anti-government placards and a coffin with the label "Trade Unionism." Readers were also told that: "Conspicuous in the procession was a Eureka flag, a replica of the flag Peter Lalor's followers carried at the Eureka Stockade in 1854." It was reported that two protesters were injured and five arrested "In a fight for the Eureka flag" where the "strikers resisted, and blows were struck. Police, caught up in the melee, drew batons and used them."[70]

The Eureka Flag was also used by supporters of Gough Whitlam after he was dismissed as prime minister.[71] In 1979, the Northcote City Council began flying the Eureka Flag from its Town Hall to mark the 125th anniversary of the uprising, and continued until at least 1983.[72][73] During a 1983 royal tour, a republican supporter informally presented a small Eureka Flag to Diana, Princess of Wales, who did not recognise it. The event prompted a cartoon of the royal couple with Charles, Prince of Wales, observing "Mummy will not be pleased."[74]

The sesquicentenary of the Eureka Stockade occurred in December 2004, and the Eureka Flag was used extensively during the events that were organised to promote awareness of the occasion. It was flown within each state parliament building in Australia, the federal senate, and most prominently atop the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson made the Eureka Flag a federal election issue in 2004 saying he did not favour flying it at parliament house to mark the 150th anniversary and that "I think people have tried to make too much of the Eureka Stockade ... trying to give it a credibility and standing that it probably doesn't enjoy."[75]

The Eureka Flag has been adopted by a variety of organisations, including the City of Ballarat and University of Ballarat, that use stylised versions of the 'Southern Cross' in their official logo. It is used by several trade unions, including the CFMEU and ETU. The Eureka flag flies permanently over the Melbourne Trades Hall. The Prospectors and Miners Association of Victoria use the Eureka Flag as their official flag and would seem to be the only 'rightful' and 'correct' user of the flag today. They are the only lobby and interest group representing the rights of Gold Miners and Prospectors in the State of Victoria as the original Eureka Stockade rebellion members were.[76] In 2016 the Australia First Party formally adopted a logo featuring the Eureka flag.[77]

Sporting clubs have also used the flag as a symbol including the Melbourne Victory and Melbourne Rebels. Melbourne Victory supporters adopted it as a club flag for its foundation year in 2004, however it was subsequently briefly banned[78] at A-League games by the Football Federation of Australia, but rescinded in the face of criticism from the Victorian general public. The Football Federation of Australia claimed that the ban was "unintentional".

The crew of HMAS Ballarat wear Eureka Flag insignia on their uniforms.[citation needed] The ship also occasionally flies the Eureka Flag from its mainstay alongside the Australian White Ensign.[79]

Standardised design

The modern design of the Eureka Flag is an enhanced and different version from the 1854 original with blue key lines around each of five equal stars. It is frequently made in the proportions of 20:13. Although the flag is designed as a representation of the Southern Cross, a constellation located in southern skies and thus only visible to viewers in the southern hemisphere, the stars are arranged differently from the arrangement of stars in the constellation itself. The "middle" star (Epsilon Crucis) in the constellation is off-centre, and near to the edge of the "diamond", while the Eureka Flag shows it in the centre. The Eureka Flag is only a stylised version of the more widely known pattern.

Derivatives and variants

The Lambing Flat riots was a series of violent anti-Chinese demonstrations that took place in the Burrangong region, in New South Wales, Australia, on the goldfields at Spring Creek, Stoney Creek, Back Creek, Wombat, Blackguard Gully, Tipperary Gully and Lambing Flat (now Young, New South Wales). The miners local vigilante committee was known as the Miner's Protection League. On 30 June 1861, seven hundred miners led by a brass band went about sacking the grog-shops which were havens for thieves before turning their attention to the Chinese section. Most fled, but two Chinese who stayed to fight were killed and 10 others badly injured. There were further incidents throughout 1861, with the Chinese who returned again being set upon. Another large gathering called for 14 July, Bastille Day, was eventually read the riot act and had shots fired over their heads before being dispersed by mounted troopers. The trouble gradually subsided as more soldiers and marines were called in from Sydney. In 1870 the town was renamed in honour of governor Sir John Young.

The Lambing Flat banner was painted on a tent-flap, now on display at the Lambing Flat Museum, bearing a Southern Cross superimposed over a St Andrew's cross with the inscription "ROLL UP. ROLL UP. NO CHINESE."[80] It has been claimed by some that the banner, which served as an advertisement for a public meeting that presaged the Lambing Flat riots, was intended as a tribute to the Eureka Flag.[citation needed]

A red Eureka Flag was used by communists during the late 1970s early 1980s. As the design was little seen and the group using it was on fringe of the communist movement the red Eureka Flag soon disappeared from view.[citation needed] The red Eureka Flag has since been adopted by the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union. The AMWU, however, has no links to communism and is instead affiliated with the Australian Labor Party.

Vintage star spangled Eureka Flag

According to Whitney Smith, writing in 1975, the Eureka Flag "perhaps because of its association with labour riots and a time of political crisis in Australian history, was long forgotten. A century after it was first hoisted, however, Australian authors began to recognise that it had been an inspiration, both in spirit and design, for many banners up to and including the current official civil and state flags of the nation."[81]

Prior to the Eureka flag going on permanent display to the public it was often featured with no cross and free floating stars as per the Australian national flag, such as in the 1949 motion picture Eureka Stockade starring Chips Rafferty.

Other Eureka flags

The disputed first report of the attack on the Eureka Stockade also makes reference to a Union Jack being flown during the battle that was then captured, along with the Eureka flag, by the foot police.[82]

The investigation carried out by William Withers in the late nineteenth century revealed that two women, Mrs Morgan and Mrs Oliver, claimed to have sewn a starry flag around the time, but "they could not positively identify it as the one flown at Eureka."[83] John Wilson recalls that the Eureka flag was taken down by Thomas Kennedy at sundown on 2 December 1854 and stored in his tent "for safe keeping."[84] However, when the military and police arrived the next day in the early hours of the morning the Eureka flag was already flying above the stockade. Frank Cayley has concluded that: "Wilson's flag was undoubtedly one of several flags, in various designs, that were made at Eureka."[85] His colleague and fellow Eureka investigator, Melbourne journalist Len Fox, has also stated: "Flags were popular on the goldfields, and it may well be that among the diggers at Ballarat were smaller (and different) versions of the Eureka flag."[86]

With respect to the provenance of the star spangled Eureka Flag, Withers interviewed police officer John McNeil for his report published in the Ballarat Star, 1 May 1896 edition, who recalled a meeting at Bakery Hill where Robert McCandlish "unbuttoned his coat and took out and unfurled a light blue flag with some stars on it, but there was no cross on it."[87]

Eureka Jack mystery

Since 2012 various theories have emerged, based on the Argus account of the battle dated 4 December 1854, and an affidavit sworn by Private Hugh King three days later as to a flag being seized from a prisoner captured at the stockade, that a Union Jack, known as the Eureka Jack may also have been flown by the rebels.

In his Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution, Peter FitzSimons has stated:

"In my opinion, this report of the Union Jack being on the same flagpole as the flag of the Southern Cross is not credible. There is no independent corroborating report in any other newspaper, letter, diary or book, and one would have expected Raffaello Carboni, for one, to have mentioned it had that been the case. The paintings of the flag ceremony and battle by Charles Doudiet, who was in Ballarat at the time, depicts no Union Jack. During the trial for high treason, the flying of the Southern Cross was an enormous issue, yet no mention was ever made of the Union Jack flying beneath."[88]

Hugh King who was with the 40th regiment swore in a signed contemporaneous affidavit that he recalled:

"... three or four hundred yards a heavy fire from the stockade was opened on the troops and me. When the fire was opened on us we received orders to fire. I saw some of the 40th wounded lying on the ground but I cannot say that it was before the fire on both sides. I think some of the men in the stockade should - they had a flag flying in the stockade; it was a white cross of five stars on a blue ground. - flag was afterwards taken from one of the prisoners like a union jack – we fired and advanced on the stockade, when we jumped over, we were ordered to take all we could prisoners..."[89]

During the committal hearings for the Eureka rebels there would be another Argus report dated 9 December 1854 stating that two flags had been seized in the following terms:

"The great topic of interest to-day has been the proceedings in reference to the state prisoners now confined in the Camp. As the evidence of the witnesses in these cases is more reliable information than that afforded by most reports, I shall endeavor to give you an abstract of it." Hugh King had been called upon to give further testimony live under oath in the matter of Timothy Hayes and in doing so went into more detail than in his affidavit, as it was reported the Union Jack like flag was found:

"... rollen up in the breast of a[n] [unidentified] prisoner. He [King] advanced with the rest, firing as they advanced ... several shots were fired on them after they entered [the stockade]. He observed the prisoner [Hayes] brought down from a tent in custody."[90]

Military historian and author of Eureka Stockade: A Ferocious and Bloody Battle, Gregory Blake, has conceded the rebels may have flown two battle flags as they were claiming to be defending their British rights. Blake leaves open the possibility that the flag being carried by the prisoner had been souvenired from the flag pole as the routed garrison was fleeing the stockade. Once taken by Constable John King the Eureka flag was placed beneath his tunic in the same fashion as the suspected Union Jack was found on the prisoner. According to The Eureka Encyclopedia, in 1896 Sergeant John McNeil recalled shredding a flag at the Spencer Street Barracks in Melbourne at the time that was said to be the Eureka flag,[91] but which Blake believes may have actually been the mystery Eureka Jack.[92] There is another theory that the Eureka Jack was an 11th hour response to divided loyalties in the rebel camp.[93] Peter Lalor made a blunder by choosing "Vinegar Hill" - the site of a battle during the 1798 Irish uprising - as the rebel password. This led to waning support for the Eureka rebellion as news that the issue of Irish independence had become involved began to circulate.[94][95] In The Revolt at Eureka, part of a 1958 illustrated history series for students, the artist Ray Wenban would remain faithful to the first reports of the battle with his rendition featuring two flags flying above the Eureka Stockade.[96]

In 2013 the Australian Flag Society announced a worldwide quest and $10,000 reward for more information and materials in relation to the Eureka Jack mystery.[93][97]

See also

References

- ^ Justin Corfield, Dorothy Wickham, Clare Gervasoni, The Eureka Encyclopedia (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 2004), p. xiii.

- ^ a b "The flag of the Southern Cross (Eureka Flag)". Art Gallery of Ballarat. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b Dorothy Wickham, Clare Gervasoni, Val D’Angri, The Eureka Flag: Our Starry Banner (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 2000).

- ^ "Eureka Flag, Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number H2097". Victorian Heritage Database. Heritage Victoria. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ National Trust, First Victorian Icons Named

- ^ John Wilson, 'The Starry Banner of Australia', The Capricornian (Rockhampton), 19 December 1885, p. 29 <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/67954740>.

- ^ J.W. Wilson, The Starry Banner of Australia: An Episode in Colonial History (Brian Donaghey, Brisbane, 1963) pp. 6-7.

- ^ Ballarat Star, 14 January 1893.

- ^ The Sydney Sun, 5 May 1941, p. 5, refers to this oral tradition. See also Withers in his report in the Ballarat Star, 1 May 1896.

- ^ a b c d Anne Beggs Sunter, ‘Contesting the Flag: the mixed messages of the Eureka Flag’, paper for Eureka Seminar, University of Melbourne History Department, 1 December 2004, published in Eureka: reappraising an Australian Legend, edited by Alan Mayne, Network Books, Perth, 2007.

- ^ The Herald, 07 November 1854.

- ^ Frank Cayley, Flag of Stars (Rigby, Sydney, 1966), p. 82.

- ^ Frank Cayley, Flag of Stars (Rigby, Sydney, 1966), pp. 82-83.

- ^ Bob O’Brien, Massacre at Eureka: The untold story (Australian Scholarly Publishing, Kew, 1992), p. 81.

- ^ The Sydney Sun, 5 May 1941, p. 4, mentions issues of the Ballarat Times in the Mitchell Library. See also Len Fox, The Eureka Flag, p. 49.

- ^ Whitney Smith, The Flag Book of the United States: The Story of the Stars and Stripes and the Flags of the Fifty States (William Morrow, New York, 1975), 60.

- ^ "Flag History – Other Australian Flags – Eureka Flag". Australianflag.com.au. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Dorothy Wickham, Clare Gervasoni, Val D’Angri, The Eureka Flag: Our Starry Banner (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 2000), p. 11.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Historians discuss Eureka legend’, Lateline, 7 May 2001 (Geoffrey Blainey).

- ^ Frank Cayley, Flag of Stars (Rigby, Sydney, 1966), 76.

- ^ Eureka Flag history

- ^ Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement, 2nd ed. (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1965), 35.

- ^ J.W. Wilson, The Starry Banner of Australia: An Episode in Colonial History (Brian Donaghey, Brisbane, 1963), pp. 7-8.

- ^ J.W. Wilson, The Starry Banner of Australia: An Episode in Colonial History (Brian Donaghey, Brisbane, 1963), p. 8.

- ^ Ballarat Times, cited in The Age, 28 November 1854, p. 5.

- ^ The Age, 4 December 1854, 5.

- ^ Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham (Public Record Office, Melbourne, 1981), pp. 6-7.

- ^ Ballarat Times, 30 November 1854.

- ^ Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion (Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, 1980), 68.

- ^ Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion (Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, 1980), p. 68.

- ^ The Herald, 9 June 1931.

- ^ 'HISTORIC TREE STUMP: Where Eureka Stockaders Discussed Grievances', The Herald, 9 June 1931.

- ^ North Western Courier, 13 July 1931.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/3880680/bakery-hill-development-gets-green-light/

- ^ Justin Corfield, Dorothy Wickham, Clare Gervasoni, The Eureka Encyclopedia (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 2004), p. xiii.

- ^ Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion (Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, 1980), p. 59.

- ^ Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion (Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, 1980), p. 59.

- ^ John Wellesley Thomas, 14 December 1854, J54/1430 VPRS 1189/P Unit 92, J54/14030 VA 856 Colonial Secretary's Office, Public Record Office Victoria.

- ^ Peter Fitzsimons, Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution (Random House Australia, Sydney, 2012), p. 477.

- ^ Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion (Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, 1980), p. 98.

- ^ William Withers, History of Ballarat (Ballarat, Ballarat Heritage Services, 1999) (1870 ed.), p. 82.

- ^ Les Blake, Peter Lalor: The Man from Eureka (Belmont, Vic, Neptune Press, 1979), p. 88.

- ^ Raffaello Carboni, The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion (Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, 1980), p. 104.

- ^ R.E. Johns Papers, MS10075, Manuscript Collection, La Trobe Library, State Library of Victoria.

- ^ a b The Queen v Hayes and others, 1.

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 35.

- ^ The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 March 1855, p. 3.

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 43.

- ^ William Withers, History of Ballarat, 1870, Appendix E.

- ^ John King's letter to Melbourne Public Library of 13 September 1877 reproduced in Dot Wickham, The Eureka Flag, Our Starry Banner, Ballarat, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2000, p. 44.

- ^ William Withers, History of Ballarat and Some Ballarat Reminiscences (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 1999), p. 239.

- ^ a b "Reclaiming the Radical Spirit of the Eureka Rebellion and Eureka Stockade of 1854". Takver.com. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Walshe, R. D [1] He Found and Raised Eureka's Trampled Flag: a Tribute to Len Fox Archived 25 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Justin Corfield, Dorothy Wickham, Clare Gervasoni, The Eureka Encyclopedia (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 2004), p. 539-541.

- ^ Ballarat Courier, 14 February 1973, p. 12.

- ^ My Ballarat, September 2010.

- ^ Business News, Issue 218, May 2013.

- ^ "Eureka Flag". Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Huxley, John Eureka? An answer to that Jack in the corner gets a little bit warmer Sydney Morning Herald. 26 January 2011

- ^ Thousands march for Labour Day across Queensland Australian Broadcasting Commission. 3 May 2011

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Our Own Flag". Ausflag. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2006. Australian Flags. Australian Government Publishing Service ISBN 0-642-47134-7.

- ^ "Aussie pride: what Australians love about their country" (PDF). Mccrindle.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ http://www.alphalink.com.au/~eureka.

- ^ W.A. Spence, Australia's Awakening, p. 95, who said the meeting was on 31 August 1890. However in an article for Sydney Daily Telegraph, 14 March 1963 edition, E.J. Holloway states that the platform had been decorated with the Eureka flag on 29 August 1890. See also Len Fox, The Strange Story of the Eureka Flag, p. 17.

- ^ Grantlee Kieza, Sons of the Southern Cross (HarperCollins, Sydney, 2014), p. 301.

- ^ Anne Beggs Sunter, ‘Contesting the Flag: the mixed messages of the Eureka Flag’, paper for Eureka Seminar, University of Melbourne History Department, 1 December 2004, published in Eureka: reappraising an Australian Legend, edited by Alan Mayne, Network Books, Perth, 2007.

- ^ 'POLICE IN SERIOUS CLASH WITH STRIKERS: Battle over Eureka flag', The Argus (Melbourne), 18 March 1948, p. 3 <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/22553655>.

- ^ Michael Willis and Geoffrey Gold 'Eureka, Our Heritage' in Geoffrey Gold (ed.), Eureka; Rebellion beneath the Southern Cross (Adelaide, Rigby, 1977), pp. 101-108. See also: Les Murray, 'The Flag Rave', The Peasant Mandarin, St. Lucia, University of Queensland Press, 1978, pp. 230-244, first published in the Nation Review in 1977.

- ^ "Battle of the Eureka Flag". The Canberra Times. Vol. 54, , no. 16, 152. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 15 December 1979. p. 2. Retrieved 10 August 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Barricade against eviction". The Canberra Times. Vol. 58, , no. 17, 565. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 1 November 1983. p. 8. Retrieved 10 August 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Royal visit of William and Kate recalls Diana's Eureka moment". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ [2] Archived 15 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://pmav.org.au/

- ^ https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-04-12/anger-over-australia-first-partys-use-of-eureka-flag/7319484

- ^ Ham, Larissa (27 October 2008). "Soccer bosses flag end to Eureka moments". The Age. Melbourne.

- ^ [3] Archived 20 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frank Cayley, Flag of Stars" (Rigby, Adelaide, 1966), p. 88.

- ^ Whitney Smith, Flags Through the Ages and Across the World (McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead, 1975), p. 78.

- ^ 'By Express. Fatal Collision at Ballaarat', The Argus (Melbourne), 4 December 1854, p. 5 <http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/4801224>.

- ^ William Withers, 'The Eureka Stockade Flag', The Ballarat Star, 1 May 1896, 1.

- ^ J.W. Wilson, The Starry Banner of Australia: An Episode in Colonial History (Brian Donaghey, Brisbane, 1963) pp. 14-15.

- ^ Frank Cayley, Flag of Stars (Rigby, Sydney, 1966), p. 77.

- ^ Len Fox, Eureka and its flag (Mullaya Publications, Canterbury, 1973), p. 32.

- ^ William Withers, "The Eureka Stockade Flag", The Ballarat Star, 1 May 1896, p. 1.

- ^ Peter Fitzsimons, Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution (Random House Australia, Sydney, 2012), pp. 654 - 655, note 56.

- ^ Hugh King, 16 January 1855, Eureka Stockade:Depositions VPRS 5527/P Unit 2, Item 9, Public Record Office Victoria <http://wiki.prov.vic.gov.au/index.php/Eureka_Stockade:Depositions_VPRS_5527/P_Unit_2,_Item_9>.

- ^ 'BALLAARAT', The Argus (Melbourne), 9 December 1854, p. 5 <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4801531/554726>.

- ^ Justin Corfield, Dorothy Wickham, Clare Gervasoni, The Eureka Encyclopedia (Ballarat Heritage Services, Ballarat, 2004), p. 357.

- ^ Gregory Blake, Eureka Stockade: A ferocious and bloody battle (Big Sky Publishing, Newport, 2012), pp. 243 - 244, note 78.

- ^ a b Tom Cowie, '$10,000 reward to track down 'other' Eureka flag', The Courier (Ballarat), 22 October 2013, p. 3 <http://www.thecourier.com.au/story/1858615/10000-reward-to-track-down-the-other-eureka-flag>.

- ^ H.R. Nicholls. "Reminiscences of the Eureka Stockade", The Centennial Magazine: An Australian Monthly, (May 1890) (available in an annual compilation; Vol. II: August 1889 to July 1890), p. 749.

- ^ William Craig, My Adventures on the Australian Goldfields (Cassell and Company, London, 1903), p. 270.

- ^ Ray Wenban, The Revolt at Eureka, Australian Visual Education, volume 16, p. 27-28.

- ^ Fiona Henderson, 'Reward offered for evidence of battle's Union Jack flag', The Courier (Ballarat), 23 December 2014, p. 5.