Time Out of Joint

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

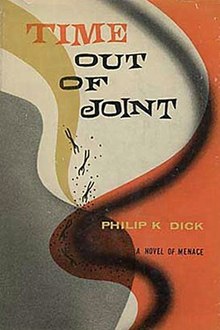

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Philip K. Dick |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Arthur Hawkins |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction, Psychological Thriller |

| Publisher | J. B. Lippincott Company |

Publication date | 1959 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 221 |

Time Out of Joint is a dystopian novel by American writer Philip K. Dick, first published in novel form in the United States in 1959. An abridged version was also serialised in the British science fiction magazine New Worlds Science Fiction in several installments from December 1959 to February 1960.

The novel epitomizes many of Dick's themes with its concerns about the nature of reality and ordinary people in ordinary lives having the world unravel around them.[1] The title is a reference to Shakespeare's play Hamlet.[2] The line is uttered by Hamlet after being visited by his father's ghost and learning that his uncle Claudius murdered his father; in short, a shocking supernatural event that fundamentally alters the way Hamlet perceives the state and the universe ("The time is out of joint; O cursed spite!/That ever I was born to set it right!" [I.V.211-2]), much as do several events in the novel.

Plot summary

Ragle Gumm lives in the year 1959 in a quiet American suburb. His unusual profession consists of repeatedly winning the cash prize in a local newspaper contest called "Where Will The Little Green Man Be Next?". Gumm's 1959 has some differences from ours: the Tucker car is in production, AM/FM radios are scarce to non-existent, and Marilyn Monroe is a complete unknown. As the novel opens, strange things begin to happen to Gumm. A soft-drink stand disappears, replaced by a small slip of paper with the words "SOFT-DRINK STAND" printed on it in block letters. Intriguing little pieces of the real 1959 turn up: a magazine article on Marilyn Monroe, a telephone book with non-operational exchanges listed and radios hidden away in someone else's house. People with no apparent connection to Gumm, including military pilots using aircraft transceivers, refer to him by name. Few other characters notice these or experience similar anomalies; the sole exception is Gumm's supposed brother-in-law, Victor "Vic" Nielson, in whom he confides. A neighborhood woman, Mrs. Keitelbein, invites him to a civil defense class where he sees a model of a futuristic underground military factory. He has the unshakeable feeling he's been inside that building many times before.

Confusion gradually mounts for Gumm. His neighbor Bill Black knows far more about these events than he admits, and, observing this, begins worrying: "Suppose Ragle [Gumm] is becoming sane again?" In fact, Gumm does become sane, and the deception surrounding him (erected to protect and exploit him) begins to unravel.

Gumm tries to escape the town and is turned back by Kafkaesque obstructions. He sees a magazine with himself on the cover, in a military uniform, at the factory depicted in the model. He tries a second time to escape, this time with Vic, and succeeds. He learns that his idyllic town is a constructed reality designed to protect him from the frightening fact that he lives on a then-future Earth (circa 1998) that is at war against lunar colonists who are fighting for a permanent lunar settlement, politically independent from Earth.

Gumm has a unique ability to predict where the colonists' nuclear strikes will be aimed. Previously Gumm did this work for the military, but then he defected to the colonists' side and planned to secretly emigrate to the Moon. But before this could happen, he began retreating into a fantasy world based largely upon the relatively idyllic surroundings of his extreme youth. He was no longer able to shoulder his responsibility as Earth's lone protector from Lunar-launched nuclear offensives. The fake town was thereby created within Gumm's mind to accommodate and rationalize his retreat to childhood so that he could continue predicting nuclear strikes in the guise of submitting entries to a harmless newspaper contest and without the ethical qualms involved with being on the "wrong" side of a civil war. While Gumm regressed by himself to a 1950s mindset, the rest of the town with a few exceptions like Black were all put in a similar state artificially, explaining why hardly anyone else could perceive anomalies.

When Gumm finally remembers his true personal history, he decides to emigrate to the Moon after all because he feels that exploration and migration, as basic human impulses, should never be denied to people by any national or planetary government. Vic rejects this belief, referring to the colonists essentially as aggressors and terrorists, and returns to the simulated town- which has lost its raison d'etre because of Gumm's escape from its environs. The book ends with some hope for peace, because the Lunar colonists are more willing to negotiate than Earth's "One Happy World" regime has been telling its citizens.

Reception

Dave Langford reviewed Time Out of Joint for White Dwarf #57, and stated that "there are classic moments, as when reality blows a fuse and a soft-drink stand disintegrates before Gumm's eyes, leaving only a bit of paper with the words SOFT-DRINK STAND."[3]

See also

- Ding an sich, a concept mentioned in the story.

- Simulated reality

- Simulated reality in fiction

- Other works of fiction with a constructed reality:

- EDtv, a 1999 American comedy film about a man whose life gets turned into a TV show.

- The Incident, a 2014 Mexican film in which the book notably appears, about people trapped in an infinite loop.

- The Truman Show, a 1998 American comedy-drama film that chronicles the life of a man who discovers he is living in a constructed reality soap opera, televised 24/7.

Sources

- Rossi, Umberto, "Just a Bunch of Words: The Image of the Secluded Family and the Problem of logos in P.K. Dick's Time Out of Joint", Extrapolation, Vol. 37 No. 3, Fall 1996.

- Rossi, Umberto, “The Harmless Yank Hobby: Maps, Games, Missiles and Sundry Paranoias in Time Out of Joint and Gravity’s Rainbow”, Pynchon Notes #52–53, Spring-Fall 2003, pp. 106–123

References

- ^ Canaan, Howard (2008). "Time and Gnosis in the Writings of Philip K. Dick". Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS). 14 (2): 335–355. ISSN 1218-7364.

- ^ "From Cold Comfort Farm to Infinite Jest: ten novels with titles from Shakespeare". The Telegraph. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Langford, Dave (September 1984). "Critical Mass". White Dwarf (Issue 57). Games Workshop: 14.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: year (link)