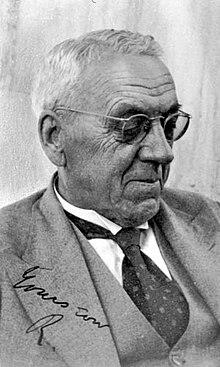

Robert Broom

Robert Broom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 November 1866 |

| Died | 6 April 1951 (aged 84) |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1928) Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal (1946) Wollaston Medal (1949) |

| Signature | |

| |

Robert Broom FRS[1] FRSE (30 November 1866 – 6 April 1951) was a Scottish South African doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University of Glasgow.

From 1903 to 1910, he was professor of zoology and geology at Victoria College, Stellenbosch, South Africa, and subsequently he became keeper of vertebrate palaeontology at the South African Museum, Cape Town.[2][3][4][5]

Life

Broom was born at 66 Back Sneddon Street in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland, the son of John Broom, a designer of calico prints and Paisley shawls, and Agnes Hunter Shearer.[6]

In 1893, he married Mary Baird Baillie, his childhood sweetheart.[7]

In his medical studies at the University of Glasgow Broom specialised in obstetrics.[8] After graduating in 1895 he travelled to Australia, supporting himself by practising medicine. He settled in South Africa in 1897,[8] just prior to the South African War. From 1903 to 1910, he was professor of Zoology and Geology at Victoria College, Stellenbosch (later Stellenbosch University), but was forced out of this position for promoting belief in evolution.[8] He established a medical practice in the Karoo region of South Africa, an area rich in Therapsid fossils. Based on his continuing studies of these fossils and mammalian anatomy he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1920. Following the discovery of the Taung child he became interested in the search for human ancestors and commenced work on much more recent fossils from the dolomite caves north-west of Johannesburg, particularly Sterkfontein Cave (now part of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site). As well as describing many mammalian fossils from these caves he identified several hominin fossils, the most complete of which was an Australopithecine skull, nicknamed Mrs Ples, and a partial skeleton that indicated that Australopithecines walked upright.[8]

Broom died in Pretoria, South Africa in 1951.

Contributions

Broom was first known for his study of mammal-like reptiles. After Raymond Dart's discovery of the Taung Child, an infant australopithecine, Broom's interest in palaeoanthropology was heightened. Broom's career seemed over and he was sinking into poverty, when Dart wrote to Jan Smuts about the situation. Smuts, exerting pressure on the South African government, managed to obtain a position for Broom in 1934 with the staff of the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria as an Assistant in Palaeontology.

In the following years, he and John T. Robinson made a series of spectacular finds, including fragments from six hominins in Sterkfontein, which they named Plesianthropus transvaalensis, popularly called Mrs. Ples, but which was later classified as an adult Australopithecus africanus, as well as more discoveries at sites in Kromdraai and Swartkrans. In 1937, Broom made his most famous discovery, by defining the robust hominin genus Paranthropus with his discovery of Paranthropus robustus.[9] These discoveries helped support Dart's claims for the Taung species.

For his volume, The South Africa Fossil Ape-Men, The Australopithecinae, in which he proposed the Australopithecinae subfamily, Broom was awarded the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 1946.[10]

The remainder of Broom's career was devoted to the exploration of these sites and the interpretation of the many early hominin remains discovered there. He continued to write to the last. Shortly before his death he finished a monograph on the Australopithecines and remarked to his nephew:

- "Now that's finished ... and so am I."[11]

Spiritual evolution

Broom was a nonconformist and was deeply interested in the paranormal and spiritualism; he was a critic of Darwinism and materialism. Broom was a believer in spiritual evolution. In his book The Coming of Man: Was it Accident or Design? (1933) he claimed that "spiritual agencies" had guided evolution as animals and plants were too complex to have arisen by chance. According to Broom, there were at least two different kinds of spiritual forces, and psychics are capable of seeing them.[12] Broom claimed there was a plan and purpose in evolution and that the origin of Homo sapiens is the ultimate purpose behind evolution. According to Broom "Much of evolution looks as if it had been planned to result in man, and in other animals and plants to make the world a suitable place for him to dwell in."[13]

After discovering the skull of Mrs. Ples, Broom was asked if he excavated at random, Broom replied that spirits had told him where to find his discoveries.[14]

Publications

Among hundreds of articles contributed by him to scientific journals, the most important include:

- "Fossil Reptiles of South Africa" in Science in South Africa (1905)

- "Reptiles of Karroo Formation" in Geology of Cape Colony (1909)

- "Development and Morphology of the Marsupial Shoulder Girdle" in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1899)

- "Comparison of Permian Reptiles of North America with Those of South Africa" in Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (1910)

- "Structure of Skull in Cynodont Reptiles" in Proceedings of the Zoölogical Society (1911).

- The South Africa Fossil Ape-Men, The Australopithecinae (1946).

Books

- The origin of the human skeleton: an introduction to human osteology (1930)

- The mammal-like reptiles of South Africa and the origin of mammals (1932)

- The coming of man: was it accident or design? (1933)

- The South African fossil ape-man: the Australopithecinae (1946)

- Sterkfontein ape-man Plesianthropus (1949)

- Finding the missing link (1950)

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina fossils (with images)

- Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research

- John Talbot Robinson, co-discoverer of Mrs Ples.

Notes and references

- ^ Watson, D. M. S. (1952). "Robert Broom. 1866-1951". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 8 (21): 36–70. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1952.0004. JSTOR 768799.

- ^ Richmond, J. (2009). "Design and dissent: Religion, authority, and the scientific spirit of Robert Broom". Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and its Cultural Influences. 100 (3): 485–504. doi:10.1086/644626. PMID 19960839.

- ^ Clark, W. E. (1951). "Dr. Robert Broom, F.R.S". Nature. 167 (4254): 752. doi:10.1038/167752a0. PMID 14833380.

- ^ "ROBERT Broom". Lancet. 1 (6660): 915–916. 1951. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(51)91306-2. PMID 14825857.

- ^ "ROBERT Broom, M.D., F.R.S". British Medical Journal. 1 (4711): 889. 1951. PMC 2069052. PMID 14821559.

- ^ Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 (PDF). July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

- ^ Findlay, George (1972). Dr. Robert Broom, F.R.S.; palaeontologist and physician, 1866-1951: a biography, appreciation and bibliography. A. A. Balkema.

- ^ a b c d "Robert Broom". South African History Online. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ Johanson, Donald; Edey, Maitland (1990). Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind. Simon and Schuster. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-671-72499-3.

- ^ "Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Morell, Virginia (2011). Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind's Beginnings. Simon and Schuster. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4391-4387-2.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2001). Reconciling science and religion: the debate in the early-twentieth-century Britain. pp. 133–134.

- ^ Lewin, Roger (1997). Bones of contention: controversies in the search for human origins. p. 311. ISBN 0226476510.

- ^ Dreyer, Nadine (2006). A century of Sundays: 100 years of breaking news in the Sunday times, 1906-2006. p. 119.

External links

- Biographies: Robert Broom TalkOrigins Archive

- Robert Broom: A Short Bibliography of his Evolutionary Works, MPRInstitute.org site.

- British metaphysics as reflected in Robert Broom's evolutionary theory, translation of an article by Václav Petr published in Bulletin of the Czech Geological Survey, 75(1): 73-85. Praha 2000. Text and photos displayed entire at the MPRInstitute.org site.

- Use dmy dates from June 2012

- 1866 births

- 1951 deaths

- 20th-century British scientists

- 20th-century British zoologists

- 20th-century Scottish medical doctors

- 20th-century Scottish writers

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Non-Darwinian evolution

- Paleoanthropologists

- People from Renfrewshire

- Physical anthropologists

- Royal Medal winners

- Scottish palaeontologists

- Scottish scholars and academics

- Scottish spiritualists

- South African obstetricians

- South African paleontologists

- South African writers

- Stellenbosch University faculty

- Taxa named by Robert Broom

- Theistic evolutionists

- Wollaston Medal winners

- Writers from Paisley, Renfrewshire