Spotted sandgrouse

| Spotted sandgrouse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pterocliformes |

| Family: | Pteroclidae |

| Genus: | Pterocles |

| Species: | P. senegallus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pterocles senegallus (Linnaeus, 1771)

| |

The spotted sandgrouse (Pterocles senegallus) is a species of ground dwelling bird in the family Pteroclidae. It is found in arid regions of northern and eastern Africa and across the Middle East and parts of Asia as far east as northwest India. It is a gregarious, diurnal bird and small flocks forage for seed and other vegetable matter on the ground, flying once a day to a waterhole for water. In the breeding season pairs nest apart from one another, the eggs being laid in a depression on the stony ground. The chicks leave the nest soon after hatching and eat dry seed, the water they need being provided by the male which saturates its belly feathers with water at the waterhole. The spotted sandgrouse is listed as being of "least concern" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in its Red List of Threatened Species.

Description

The spotted sandgrouse reaches a length of about 33 centimetres (13 in). The male has a small reddish-brown nape surrounded by a band of pale grey that extends to the bill and round the neck in a collar. The chin, neck and throat are orange and the breast grey. The upper parts are pinkish-grey with dark flight feathers and dark patches on the wings, tail and lower belly. The primaries are pale with dark trailing edges, a fact that distinguishes this species from the crowned sandgrouse (Pterocles coronatus) which has completely dark primaries. The female also has an orange throat region but is generally duller in plumage than the male. The body colour is greyish-brown liberally spotted with small dark markings and with dark patches on the wings, tail and lower belly. The central tail feathers in both sexes are elongated but not to the extent that they are in the pin-tailed sandgrouse (Pterocles alchata). When flying overhead, a dark belly stripe is visible.[2][3]

Distribution and habitat

The spotted sandgrouse is found in North Africa and the Middle East. In Africa its range extends through Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Mali, Mauritania, Chad and Niger. In the Middle East it is native to Oman, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Jordan, Syria, Iran, Iraq and Afghanistan and its range extends as far as Pakistan and north west India. In 2016, a flock of around a hundred birds arrived at Kutch after a gap of 19 years. [4] It has also been recorded as a vagrant in Italy, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey.[5] It inhabits deserts and semi-arid countryside and is largely resident although there is some local movement of flocks.[2] The population size has not been firmly established but it seems to be stable and the bird seems to be common over most of its extensive range. It is listed as being of "least concern" by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[5]

Behaviour

The spotted sandgrouse has a rapid wing beat and flies swiftly. Its call is a musical "queeto-queeto" which distinguishes it from other species of sandgrouse with similar plumage.[2]

The spotted sandgrouse is a ground-dwelling bird and feeds on seeds and other plant material that it finds among the scrubby vegetation of its dry habitat.[2] During the breeding season it is solitary but at other times of year it is gregarious. Flocks move into a new feeding ground after a storm has stimulated new green growth. In the Sahara the spotted sandgrouse are particularly fond of a species of spurge and concentrate on this until the foliage begins to parch, after which the birds return to their normal diet of seeds. These are abundant on the desert floor, remaining in a dormant state until rain occurs.[6] The birds are very wary and easily frightened. Their chief enemy is the lanner falcon which flies rapidly just above the ground and scoops up any unwary bird. The sandgrouse strategy is to have one bird flying high overhead. When it sees an approaching falcon it gives a warning call and the other sandgrouse freeze. So good is their camouflage that the raptor is unable to detect them and flies on.[7] Sandgrouse need to make a daily journey to a drinking hole, which may be many kilometres from their feeding ground. They land a short distance from the water and maintain a sentinel system here too as, beside the falcons, mammal predators may lurk nearby and nomads may water their herds. When all is safe, another distinctive call from the sentinel bird sends all the others to the pool where their daily water needs are taken up within about fifteen seconds.[8]

The journey to the waterhole is undertaken at around dawn when the air is cool. Later in the day, when the air temperature may reach over 50 °C, the birds are inactive and have the ability to increase their thermal insulation when the air temperature exceeds their body temperatures. At very high temperatures they also resort to gular fluttering and gaping to cool themselves.[9] At night, several flocks coalesce and fly off into the rocky desert far away from any vegetation. Each bird scrapes itself a shallow sleeping hollow by moving from side to side. There are no jerboas or other small mammals in these barren wastes so foxes and jackals do not roam there at night and the birds are safe.[7]

Life cycle

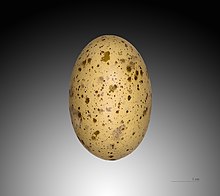

In the Sahara, breeding takes place in the hottest part of the summer on a stony desert plain. When choosing a nest site, the female scrapes several trial hollows before selecting one of them. The main criterion for selection seems to be the porous nature of the underlying rock. Spongy rock heats up less in the sun and provides a cool spot to nest. Also desirable are one or two "cover stones" close by, chosen because their dense structure attracts dew at night, moisture which drains into the soil and gets absorbed by the porous rock which helps keep the nest cool by day.[10] The nest is made in a shallow depression in the ground without any bedding material and two, occasionally three, eggs are laid. The eggs are elongated ovals in shape, buff with grey and brown blotches and speckles. Their colour and shape makes them difficult to distinguish from the pebbles lying around them. Both parents incubate the eggs and their cryptic colouration makes them almost invisible when sitting on the nest. The eggs hatch after about 20 days.[2]

The young are precocial and already covered in down when they emerge from the eggs. Soon after they are hatched the female leads the chicks to one of the many wadis that wind across the plains and there she teaches them to peck at and ingest seeds. It is four or five weeks before they are fledged and able to fly. Meanwhile, the problem of supplying them with water is solved by the male which has specially adapted, absorbent down on his belly. While at the waterhole he immerses himself in the water to saturate the plumage which absorbs a quantity that is sufficient for the chicks to last them until the following day.[2] When he leaves the waterhole with his water-laden feathers, the male emits a repeated high-pitched "queet - queet - queet" calls. When the female and chicks pick up the sounds of his approach, they reciprocate, and by this means the male can find his family even when they have moved away from the nest. On his arrival he assumes an upright posture and raises his wings, displaying the wet belly feathers. This is the sign for the chicks to approach and stand underneath him with their beaks upturned and suck the fluid from between the feathers.[11]

If danger threatens, the chicks crouch under a plant or any cover that offers, their dappled brown down merging into the desert scene. The parents are very vigilant in defence of their family. If a jackal approaches, an adult gives a warning cry and all crouch down and freeze. Usually the enemy fails to notice them and passes by. If it gets too close, one of the parents tries to lure it away by flapping along the ground, pretending to be injured and helpless. When the jackal has been led far enough away, the adult "recovers" and flies off. After three or four days, the chicks can be left alone while both parents visit the water hole, and the chicks can guide them back with their "queet - queet" cries.[12]

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2012). "Pterocles senegallus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d e f Gooders, John, ed. (1979). Birds of Heath and Woodland: Spotted Sandgrouse. London: Orbis Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 0856133809.

- ^ Madge, Steve (2003). Pheasants, Partridges and Grouse: A Guide to the Pheasants, Partridges, Quails, Grouse, Guineafowl, Buttonquails and Sandgrouse of the World. A & C Black. p. 164. ISBN 0713639660.

- ^ "Spotted sandgrouse seen in Kutch after 19 years". The Times of India. 2017-02-05. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- ^ a b "Spotted Sandgrouse Pterocles senegallus". Birdlife International. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ George, 1978. p. 180

- ^ a b George, 1978. pp. 157–158

- ^ George, 1978. pp. 159–160

- ^ Thomas, David H.; Robin, A. Paul (1977). "Comparative studies of thermoregulatory and osmoregulatory behaviour and physiology of five species of sandgrouse (Aves: Pterocliidae) in Morocco". Journal of Zoology. 183 (2): 229–249. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1977.tb04184.x.

- ^ George, 1978. pp. 186–188

- ^ Maclean, Gordon L. (1983). "Water transport by sandgrouse". BioScience. 33 (6): 365–369. doi:10.2307/1309104. JSTOR 1309104.

- ^ George, 1978. pp. 181–182

Bibliography

- George, Uwe (1978). In the Deserts of this Earth. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-89777-7.

External links

- Oriental Bird Images: Spotted Sandgrouse Photos of spotted sandgrouse in the wild.