Milpa Alta

Milpa Alta | |

|---|---|

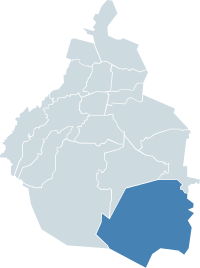

Milpa Alta within the Federal District | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Federal entity | National Capital |

| Established | 1903 |

| Named for | Monastic community |

| Seat | Av. México, esq. Constitución S/N Col. Villa Milpa Alta |

| Government | |

| • Jefe delegacional | Francisco García Flores (PRD) |

| Area | |

• Total | 286.234 km2 (110.516 sq mi) |

| Population 2010 [2] | |

• Total | 130,582 |

| • Density | 460/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central Daylight Time) |

| Postal codes | 04000 – 04980 |

| Area code | 55 |

| Website | http://www.milpa-alta.df.gob.mx/ |

Milpa Alta is one of the 16 alcaldías into which Mexico's capital, Mexico City is divided. It lies in the southeast corner of the nation's capital, bordering the State of Mexico and Morelos. It is the second largest and most rural of all the boroughs with the lowest population. It is also one of the most traditional areas of the city, with over 700 religious and secular festivals during the year and an economy based on agriculture and food processing, especially the production of nopal cactus, barbacoa and mole sauce.

Geography and environment

The borough of Milpa Alta is located in the southeast of the Federal District of Mexico City bordering the boroughs of Xochimilco, Tláhuac and Tlalpan, with the state of Morelos to the south and the State of Mexico to the west.[3] It has the second largest territorial extension after Tlalpan, occupying 268.6km2.[3][4]

The terrain is rugged mostly consisting of volcanic peak along with some small flat areas mostly formed in the Cenozoic Era.[4] City officials have classified the entire borough as a conservation zone, important for its role as an aquifer recharge area as well as its forests. Forest, farmland and grazing areas constitute 98.1% of the total surface area.[5]

It has an average altitude of 2,420 meters above sea level with altitudes varying between 2,300 and 3,600.[3] It is part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Sierra Chichinautzin volcanic mountain chain, which separates the Federal District from the state of Morelos.[4] The borough is divided into three zones: Ajusco-Teuhtli, the lowest elevations, Topilejo-Milpa Alta in the medium range and Cerro-Tlicuaya at the highest elevations.[6] The main elevations are volcanic and include Cuautzin (3,510), Tulmiac, Ocusacayo (3,220), La Comalera (3,230), San Bartolo (3,200), Tláloc (3,510), Chichinautzin (3,470), Yecahuazac, Quimixtepec, El Oclayuca (3,140), El Pajonal (3,100), El Ocotécatl (3,480), Acopiaxco (3,320), Tetzacoatl (3,310), Tehutli (2,800) Cilcuayo (3,580), Nepanapa (3,460), Texalo (3,560), Oclayuca (3,390), San Miguel (2,988) .[4]

The area belongs to the Amacuzac River basin but only small streams run on the surface.[3] It has ample surface water but confined to small springs and streams which over time have formed a succession of narrow valleys or micro-basins, which are important for recharging the Valley of Mexico’s aquifers. These micro-basins include Cilcuayo, Río Milpa Alta and Cocpiaxco and contain the borough’s main towns.[4]

Most of the area has a temperate climate, with cold climates found at the highest elevations.[6] The average annual temperature is 15.6 °C (60.1 °F) with average lows at 13.7 °C (56.7 °F) and averages highs at 16.6 °C (61.9 °F). Average annual precipitation is 731 mm (28.78 in). Freezing temperatures occur occasionally from October to March especially in the higher elevations. The windiest months are February and March. On the Koppen scale, its climate is described as C (W2) (w) b (i’) which signified a relatively moist climate, with a rainy season in the summer especially in July and August. However, the climate varies substantially in the territory based mostly on altitude, with six sub-climates: C(E)(w2) which is relatively cold, C(E)(m) also relatively cold but wetter, C(w1) a temperate climate, C (w2) a températe and relatively wet climate, C ( w1) temperate and relatively dry and C ( w2) which is relatively cold with rains falling mostly in the highest areas.[4]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 15.7 (0.62) |

8.1 (0.32) |

13.5 (0.53) |

30.2 (1.19) |

65.5 (2.58) |

121.4 (4.78) |

142.5 (5.61) |

152.4 (6.00) |

124.3 (4.89) |

52.8 (2.08) |

12.8 (0.50) |

8.9 (0.35) |

748.1 (29.45) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 6.0 | 9.8 | 16.5 | 19.5 | 20.1 | 17.7 | 8.5 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 108.6 |

| Source: Servicio Meteorológico National[7] | |||||||||||||

The area has a number of species found nowhere else. The natural vegetation is mostly forest with a mix of pine, oyamel fir and holm oak, with some concentrations of Abies religiosa. The most intact forest is found in the small canyons of the Nepanapa volcano and the west side of the Tláloc volcano. Other vegetation include fruit trees such as tejocote (Crataegus pubescens), capulin (Prunus serotona ssp capulli) blackberry (Rubus adenotrichus) and well as various scrubs, grass and flowers. The rugged terrain presents a number of micro climates which favor certain species. Depending on conditions oak, cedar, strawberry trees (Arbutus), pirul (Schinus molle), tepozan (Buddleia cordata), nopal cactus and maguey can be found.[4] Wildlife includes 59 species of mammals such as zacatuche rabbits (Romerolagus diazi), which in danger of extinction, along with coyotes, deer, lynx and moles. However, only sixteen of these species are still commonly seen because of habitat destruction.[4] Species such as wild boar, bobcats and opossums are extinct in the area.[6] There are about 200 bird species native to the area in 128 classes, 33 families and eleven orders. Eighty percent of the species live in the area year round. There are twenty four amphibian species from ten classes, seven families and two orders and fifty six species of reptiles from thirty one classes, ten families and two orders. A notable areas for these two classes of animal is the corridor between the Ajusco and Chichinautzin mountains.[4]

While named after Villa Milpa Alta, the borough is not concentrated on a single community like Tlahuac or Xochimilco but rather is composed of twelve main towns all of which are rural. This limits the area’s connectivity with the urban zone of Mexico City.[5][8] Main communities in the borough include San Pedro Atocpan, Villa Milpa Alta (formerly called Malacachtepec), San Bartolome Xicomulco, San Francisco Tecoxpa, Santa Ana Tlacotenco, San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan, San Juan Tepanahuac, San Agustin Ohtenco, San Antonio Tecómitl, San Pablo Oztotepec and San Jerónimo Miacantla.[3][4] San Agustin Ohtenco is considered to be the smallest community in the Federal District of Mexico City.[3] These main towns are subdivided into twenty nine neighborhoods called barrios and there are 225 communities in the borough total.[5][9] Villa Milpa Alta has seven barrios, San Mateo (the largest), La Concepción, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, San Agustin, Santa Martha and La Luz.[10]

Demographics and Culture

With a population of 130,592 as of 2010[update], Milpa Alta has the lowest population of Mexico City’s sixteen boroughs.[9][11] About half of the borough’s residents live in or near Villa Milpa Alta and about eighty percent are under forty.[10] It is also one of the city’s most rural and traditional areas. There is a dual system of government, administrative and agricultural, with the latter mostly tasked with the administration of common lands. The social organization of the area is traditional, based on families headed by a male, nuclear in the towns and extended in the more rural areas.[6] Men still hold most of the paying jobs, with most women classed as homemakers, although many of these work in family business, generally for no salary.[10] While it has the lowest crime rates overall, it does have problems with alcoholism in men leading to domestic violence.[11] The borough is gaining population from migration from places like the State of Mexico, Puebla and Oaxaca.[6] and few people migrate out.[12]

The borough contains a number of towns and localities. Those considered by the government to be urban (with 2010 population figures in parentheses) are: San Antonio Tecómitl (24,397), Villa Milpa Alta (18,274), San Pablo Oztotepec (15,507), San Salvador Cuauhtenco (13,856), San Francisco Tecoxpa (11,456), Santa Ana Tlacotenco (10,593), San Pedro Atocpan (8,283), San Bartolomé Xicomulco (4,340), San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan (3,676), and San Nicolás Tetelco (3,490).[13] In addition, there are approximately 250 rural settlements with populations each of less than 1,000.[13]

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the area was dominated by the Nahuas .[14] Its one of the few places left in the city with Nahuatl speaking communities, with 4,007 people speaking an indigenous language as of 2010[update].[9][11] The use of Nahuatl is widespread in the borough,[15] with the most concentrated in the towns of Santa Ana Tlacotenco, San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan and San Pablo Oztotepec. Ethnic Nahuas are found in all of the borough’s main towns.[6][14] There are also efforts to preserve and promote the use of the language in the borough.[15]

The Nahuas are primarily Catholic with a number of indigenous beliefs still remaining and blended in. Most of these have to do with the agricultural cycle, often represented by veneration to the saints. Traditional medicine is still practiced by a number of Nahuas in combination with modern medicine. Starting in the 1950s, evangelical movements such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses have made inroads into the area.[6] Traditional housing among the Nahuas is of adobe, but these are being replaced by cement and cinderblock constructions. Traditional handcrafts include embroidered clothing and articles made from maguey fiber (ixtle).[6] The current community struggles to maintain its identity and culture and to prevent being absorbed into the urban sprawl of Mexico City. One way of doing this is through ecotourism on tribal land including guided hikes, zip lines, temazcals and camping. The community also sponsors reforestation events.[14]

The borough lacks theaters, shopping centers, supermarkets and hotels.[11] However, it is one of the boroughs in the city that conserves many of its traditional religious festivals, with about 700 per year, about two per day somewhere in the borough.[11] these fairs and festivals bring 1,200,000 visitors each year to the borough.[16] Each community in the borough, including the twelve main towns and each of these towns’ neighborhoods has a patron saint celebrated once a year.[6] The areas with the most festivals and other events are San Francisco Tecoxpa, San Pedro Atocpan, San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan, San Salvador Cuauhtenco, Santa Ana Tlacotenco, San Pablo Ozotepec, San Agustín Ohtenco, Villa Milpa Alta, San Jerónimo Miacatlán and San Juan Tepanahuac.[16] The most important saint day in the entire borough is that of Our Lady of the Assumption in August.[6] Other important religious events include the passion play, held jointly by the towns of San Francisco Tecoxpa, San Pedro Atocpan, San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan and San Antonio Tecómitl and requires six months of preparations. Carnival is celebrated in San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan, San Antonio Tecómitl, San Pablo Oztotepec and Villa Milpa Alta.[16] Day of the Dead is celebrated in the borough with altars, the cleaning and decorating of gravesites, masses and vigils like many other places in Mexico but it is also celebrated with the release of sky lanterns in communities such as San Agustin Ohtenco, as well as publicly held events such as concerts, the creation of monumental paper mache skulls and even Mesoamerican ball games.[17] Holy Week is very important in the borough, especially the Passion Play held each year to reenact the passion and death of Jesus. The event involves over sixty actors, all residents of the borough chosen yearly. The current tradition was started in 1905, although it was suspended during the Mexican Revolution. The scenes of the play are enacted in several locations. Palm Sunday in San Agustin el Alto, the Asunción parish to the main church in Villa Milpa Alta for Good Friday .[18]

Secular events include the Festival of Corn and Pulque in San Antonio Tecomitl in September,[19] Feria de la Nieve (Ice Cream Fair) in San Antonio Tecomitl in March, Feria Ganadera, Gastronómica y Artesanal (Livestock, Gastronomy and Handcraft Fair) in San Pablo Ozotepec in April, the Festival de Juegos Autóctonos celebrating native toys in San Juan Tapanáhuac,[16] the annual fair of San Lorenzo Tlacoyucan in August,[20] and the entire borough celebrates the founding of Villa Milpa Alta on 22 August with a Regional fair and lighting of a New Fire in the crater of the Teutli volcano. In 2012, this event celebrated the town’s 480th anniversary.[20]

The borough is home to four significant balloon events, which together are called the Magic Route of Light. It begins with the Festival Multicultural de Globos de Cantolla (Multicultural Festival of Sky Lanterns) in September in Santa Ana Tlacotenco, with the main event of 3000 lanterns launched at once. It is followed by the Concurso Nacional de Globos y Faroles de Papel de China and the Encuentro Internacional de Constructores de Globos de Papel in San Agustin Ohtenco and San Antonio Tecomitl in November. The last is the Noche de Luces (Night of Lights) in San Francisco Tecoxpa in late November.[21]

History

The name Milpa Alta means “high cornfield.” “Alta” means high in Spanish and “milpa” is a Mexican Spanish word from Nahuatl referring to cornfields interspersed with other crops such as squash and maguey.[3] The Nahua name for the area is Momochco Malacateticpac, which means “place of altars surrounded by mountains.” This name is derived from the various volcanoes in the area.[4]

The recorded history of the area begins around 1240 when a Chichimeca group migrated into the Valley of Mexico from the north and founded the Malacachtepec Momozco dominion. They formed settlements in what is now the borough in places such as Malacatepec Momoxco, Ocotenco, Texcalapa, Tototepec, Tepetlacotanco, Huinantongo and Tlaxcomulco. In 1440, Mexica leader Hueyitlahuilli subdued these settlements and installed a leader. The capital of this dominion was centered on the town of Milpa Alta, in what are now the Santa Cruz, Los Angeles, San Mateo and Santa Martha neighborhoods with the name of Malacatepec Momoxco. The area formed a strategic point controlling the road between Tenochtitlan and Oaxtepec and Cuernavaca. At this time several lakeside docks, a ceremonial center, barracks and tribute collections centers were constructed, remnants of which remain.[3][15]

The indigenous of this area, allied with the Aztecs, struggled against the Spanish for about 100 years before being subdued.[15] This caused many of the indigenous here to abandon their lands and hide in the mountains, making incursions into Spanish held territory to plunder. In 1528, a peace pact was made with these people and the following year, Spanish authorities acknowledge their right to own land and have local governors; however, they were required to pay tribute to the Spanish and convert to Christianity.[3] The Spanish mostly kept their promise to allow indigenous rule except for a brief period in the 17th century. Organizationally, it was considered to be a district of Xochimilco. Compared to the rest of the valley area, it had little contact with the Spanish, allowing it to retain much of its indigenous character.[6]

The Franciscans were in charge of evangelization, naming Our Lady of the Assumption as patron.[6] For evangelization purposes, a modest hermitage dedicated to Saint Martha was constructed with later churches constructed in Tlatatlapocoyan and San Lorenzo. In 1570, the monastery and church of the Assumption was begun, taking a century to construct.[3]

After Independence, the area was initially part of the State of Mexico. The area’s incorporation into the Federal District of Mexico City began in 1854, when the district was expanded by Antonio López de Santa Anna expanded including part of what is now Milpa Alta.[15] However, towns such as San Pedro Atocpan were municipalities in the State of Mexico in the 19th century.[22] In 1903, the Federal District of Mexico City was expanded to include the rest of Milpa Alta.[6]

During the Mexican Revolution, the area generally sympathings with the Liberation Army of the South.[3] In 1914 this army marched to Mexico City from the state of Morelos against the regime of Victoriano Huerta. Part of that march included the occupation of the Milpa Alta area, forming a base. Here Emiliano Zapata ratified the Plan of Ayala on July 19, 1914.[23]

Reorganization of the Federal District of Mexico City created the modern borough, with the government in Villa Milpa Alta in 1929.[5]

While part of the Federal District, most residents still talk about Mexico City as a separate entity.[10] However, it is part of Greater Mexico City .[5] The pace of urbanization in the borough is slower in Milpa Alta than other outlying areas of the Federal District, but the growth of Mexico City since the mid 20th century has been affecting it.[5][8] Production of corn began to decrease in the mid 20th century.[10] In the 1970s, this process began to hasten.[5] The two major problems associated with this is illegal settlements or squatting on common land and illegal logging. Both of these are most serious in San Salavador Cuauhtenco, where squatters who have been there for years demand regularization and services and enforcers of environmental laws are threatened by residents.[8][24]

Socioeconomics

Milpa Alta is officially classed as one of the poorest in the Federal District by income, with 48.6% considered to be below the poverty line.[25] However it is also considered to have a low level of socioeconomic marginalization.[9] The discrepancy is likely due to the fact that the economy is based on cash and not all economic activity is reported.[10] Most of the land is held in common, either in ejidos or other arrangements. There is a problem with the lack of formal titles to land, which has allowed irregular settlements.[6] There is a telegraph office, a post office and various city agencies. Medical attention is mostly provided by two large clinics, one administered by UNAM and the other by ISSSTE and various small ones in various towns.[6] It has little in the way of commerce and services, with no large chain stores, few banks, no movie theaters or little else in the way of entertainment.[5]

The main economic activities of the borough are agriculture and food processing. Most agriculture is still done with traditional methods with only those of greater resources using machinery such as tractors.[6] The most important crop is the nopal cactus, with fields found just about everywhere including spaces between houses in the towns.[5][11] Founded in 1986, the Feria del Nopal is held in Villa Milpa Alta in June with the aim of promoting the consumption of the paddle cactus. The main event is the culinary exhibition of dishes made with the vegetable along with cultural, social, sporting and artistic events.[3] Other important crops include corn, beans, animal feed, fava beans, peas and honey. Pulque is produced for local consumption.[6]

One important processed food in Milpa Alta is the making of barbacoa, sheep meat cooked in a pit oven lined with maguey leaves. This is made principally for weekend sales for traditional markets and street stands in most of Mexico City.[26] The most important barbacoa producing area is Barrio San Mateo in Villa Milpa Alta.[10] About three thousand sheep are slaughtered and prepared as barbacoa each week in Milpa Alta,[10] but barbacoa is increasingly being made with sheep meat imported from Australia, New Zealand and the United States as it is cheaper than that produced in Mexico.[26] The barbacoa business in the area began in the 1940s and since then has been successful enough to allow many families to send their children to school and become professionals. Despite the younger generation’s higher education, many still participate in the family business. Its success has also allowed barbacoa families to gain a certain amount of prestige in the community.[27]

Even more important is the creation of pastes and powders to make mole sauce. These are created from the grinding and blending of twenty or more ingredients, which always include a variety of chili peppers. The mole sauces made are of various types such as rojo, verde, almendrado and about twenty others with trademarks.[3][15] The main producer of mole in the borough is San Pedro Atocpan, with almost all its residents involved in its production in some way.[3] Most of this production is done in families or small cooperatives.[6] The restaurants in San Pedro Atocpan also specialize in mole and receive about 8,000 customers each week.[26][28] The Feria Nacional del Mole occurs each year in San Pedro Atocpan in October and receives thousands of visitors to the festival site as well as the forty restaurants in the town that serve meats in mole sauce.[3]

The only other industry in Milpa Alta is small handcraft workshops making articles such as leather goods, furniture and textiles.[5]

Education

Although there are various primary schools, two technical middle schools and two high school (one a vocational school run by the Instituto Politécnico Nacional), Milpa Alta has the highest adult illiteracy rate at 5.6%.[6][11] Recently a technological institute called the Instituto Technológico de Milpa Alta was opened. Another educational and cultural institution is the Fábrica de Artes y Oficio Milpa Alta. It is the second of its type in the Federal District of Mexico City, patterned after the successful Fábrica de Artes y Oficios Oriente in Iztapalapa. Its function is to provide cultural and entertainment options to residents as well as classes in various arts and trades. In addition it supports the customs and traditions of the twelve indigenous communities found in the borough.[29] It also hosts an annual Pantomime, Clown and Circus Festival sponsored by the city’s secretary of culture. The purpose of the event is to promote the circus arts.[30]

Public high schools of the Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS) include:[31]

The Otilio Montaño Library is in Tlacoyucan.[32]

Transportation

Public transportation includes thirteen major bus route connecting the borough to Metro Tasqueña, Metro Tlahuac, the Central de Abastos, La Merced Market, Xochimilco and Santa Martha Acatitla, along with 23 smaller routes which are operated by private contractors.[33] It takes about two hours by public transportation to travel from the center of Mexico City to Villa Milpa Alta. It can take up to three if traffic is bad, but lately, the subway made close Milpa Alta to the rest of the city via Tecomitl.[11]

Most of the borough is accessible by road. This has facilitated problems such as illegal logging and irregular homesteading. The main access roads to the borough are the federal highway connecting the south of the city with Oaxtepec in Morelos, the highway connecting San Pablo-Xochimilco and the Tulyehualco-Milpa Alta road.[4]

Landmarks

Most of the borough’s landmarks are churches and chapels dating from the colonial period. The Santa Marta Chapel is considered to be the founding church of Milpa Alta. From here the churches of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were founded. The first of these is the Parish of the Assumption of Mary constructed in the 16th century along with its former monastery in Villa Milpa Alta. Other colonial era churche/chapels include Nuestra Señora de la Concepción Chapel (1767), Santa Cruz Chapel, San Agustín el Alto Chapel (16th century), San Francisco de Asís Chapel (16th century), San Jeronimo Chapel (16th century), San Juan Bautista Chapel (16th, 17th and 19th centuries), San Lorenzo Martir Chapel (1605), Calvario Hermitage (16th and 17th centuries), San Pablo Apostol Parish (16th can 17th centuries), La Lupita Chapel (16th century), San Pedro Apostol Church (17th century), San Martin Chapel (16th and 17th centuries), Santa María de Guadalupe Chapel (16th and 17th centuries), San Francisco Chapel (16th century), Divino Salvador Chapel (16th century), Nuestra Señora de Santa Ana Parish (17th century) and the San Bartolome Chapel (17th century).[34]

La Casona is one of the most important civil buildings in Milpa Alta both because of its construction and because of its history. It was constructed at the end of the 19th century and was the home of Rafael Coronel. Another important structure is the former headquarters of the Liberation Army of the South, now a museum.[34]

References

- ^ "Delegación Álvaro Obregón" (PDF) (in Spanish). Sistema de Información Económica, Geográfica y Estadística. Retrieved 2011-10-10. [dead link]

- ^ 2011 census tables: INEGI Archived May 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Milpa Alta" (in Spanish). Enciclopedia de Los Municipios y Delegaciones de México Distrito Federal. 2010. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "PLAN DELEGACIONAL PARA EL DESARROLLO RURAL SUSTENTABLE" [Borough Plan for Sustainable Rural Development] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: CONSEJO DELEGACIONAL PARA EL DESARROLLO RURAL SUSTENTABLE EN LA DELEGACION MILPA ALTA.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roberto Bonilla Rodríguez (September–December 2009). "Agricultura y tenencia de la tierra en Milpa Alta. Un lugar de identidad" [Agriculture and land tenency in Milpa Alta]. Argumentos (in Spanish). 22 (61). Mexico City. ISSN 0187-5795. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Nahuas de Milpa Alta" [The Nahuas of Milpa Alta] (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Puelbos Indígenas. October 22, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS 1951-2010". Servicio Meteorológico National. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Ivan Sosa and Ariadna Bermeo (June 27, 2003). "Conservan el ultimo bastion rural del DF" [Preserve the last rural bastion of Mexico City]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d "Milpa Alta Resumen municipal" [Milpa Alta municipal summary] (in Spanish). Mexico: Government of Mexico. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Adapon, Joy. p.5

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Milpa Alta, un rincón "olvidado" de la capital" [Milpa Alta, a "forgotten" cornier of the capital]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. January 22, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ Adapon, Joy. p.52

- ^ a b "Milpa Alta". Catálogo de Localidades. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (SEDESOL). Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "La Gran Palapa Chicahuac Zacacalli" (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Angeles Gonzalez Gamio (May 15, 2011). "El señorío de Milpa Alta" [The dominion of Milpa Alta]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Secretaria de Turismo DF anuncia ferias en Milpa Alta" [The Secretary of Tourism of Mexico City announces festival in Milpa Alta]. El Financiero (in Spanish). Mexico City. March 31, 2012. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "Celebran con globos de cantoya a los difuntos en Milpa Alta" [Celebrate the dead with sky lanterns in Milpa Alta]. El Porvenir (in Spanish). Mexico City. November 2, 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ Antonio Molina Martínez. "La Semana Santa en Milpa Alta, Distrito Federal" [Holy Week in Milpa Alta, Federal District] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ SHARENII GUZMÁN ROQUE (September 29, 2012). "Invitan a degustar pulque en Milpa Alta" [Invitation to enjoy pulque in Milpa Alta]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b PHENÉLOPE ALDAZ (August 8, 2012). "Milpa Alta celebra 480 años de su fundación" [Milpa Alta celebrates 480 years since its foundation]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ Zaira Vázquez Espejo (September 21, 2012). "La Ruta Mágica de la Luz, Milpa Alta" [The Magical Route of Light, Milpa Alta]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "San Pedro Atocpan" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ Edgar Anaya. "Zapata y su paso por Milpa Alta, Distrito Federal" [Zapata and his pass through Milpa Alta] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine.

- ^ "Ven peligroso vigilar bosques de Milpa Alta" [Protecting forests seen as dangerous in Milpa Alta]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. May 18, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "Milpa Alta, Tláhuac, Iztapalapa y A. Obregón, las delegaciones más pobres" [Milpa Alta, Tláhuac, Iztapalapa and A. Obregon, the poorest boroughs]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. December 3, 2011. p. 30. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c Tatiana Adalid (May 3, 2000). "El sabor de Milpa Alta" [The flavor of Milpa Alta]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 8.

- ^ Adapon, Joy. p.50-51

- ^ "Ven Milpa Alta Te Espera, Disfruta de… Esquisitos sabores ancestrales" [Come, Milpa Alta awaits you, Enjoy Exquisite Ancestral Flavors] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Milpa Alta. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08.

- ^ "FARO de Milpa Alta" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "3ER. FESTIVAL DE PANTOMIMA, CLOWN Y CIRCO MILPA ALTA 2012" [Third Festival of Pantomime, Clown and Circus Milpa Alta 2012] (in Spanish). Mexico: Government of Mexico City. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "Planteles Milpa Alta." Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal. Retrieved on May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Inauguración de la biblioteca Otilio Montaño, en Tlacoyucan" (Archive). Milpa Alta Borough. Retrieved on May 26, 2014.

- ^ "Rutas de Acceso" [Access Routes] (in Spanish). Mexico city: Borough of Milpa Alta. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "Ven Milpa Alta Te Espera, Disfruta de… Arquítectura Vírreinal" [Come, Milpa Alta awaits you, Enjoy Colonial Architecture] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Milpa Alta. Archived from the original on 2012-01-16.

Bibliography

- Adapon, Joy (2008). Culinary Art and Anthropology. Oxford, GBR: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1847882127.

External links

- (in Spanish) Official Delegación Milpa Alta (borough) website