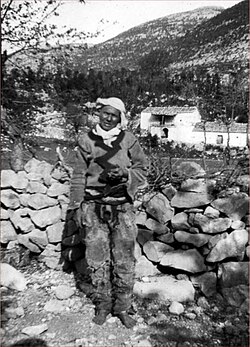

Balkan sworn virgins

Albanian sworn virgins (Template:Lang-sq) are women who take a vow of chastity and wear male clothing in order to live as men in the patriarchal northern Albanian society. To a lesser extent, the practice exists, or has existed, in other parts of the western Balkans, including Kosovo, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro,[1][2] Croatia and Bosnia.

Other terms for the sworn virgin include vajzë e betuar (most common today, and used in situations in which the parents make the decision when the girl is a baby or child), mashkull (present-day, used around Shkodra), virgjineshë, virgjereshë, verginesa, virgjin, vergjinesha, Albanian virgin, avowed virgin, muskobani, muskobanj, ostajnica (Serbian: means man-woman, manlike, she who stays), tombelija, basa, harambasa (Montenegrin), tobelija (Bosnian: bound by a vow), zavjetovana djevojka (Croatian), sadik (Stahl, Turk Moslem: honest, just).[3]

Origins

The tradition of sworn virgins developed out of the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit (Template:Lang-en, or simply the Kanun),[4] a set of codes and laws developed by Lekë Dukagjini and used mostly in northern Albania and Kosovo from the 15th century until the 20th century. The Kanun is not a religious document – many groups follow it including Roman Catholic, Albanian Orthodox, and Muslims.[5]

The Kanun dictates that families must be patrilineal (meaning wealth is inherited through a family's men) and patrilocal (upon marriage, a woman moves into the household of her husband's family).[6] Women are treated like property of the family. Under the Kanun women are stripped of many human rights. They cannot smoke, wear a watch, or vote in their local elections. They cannot buy land, and there are many jobs they are not permitted to hold. There are even establishments that they cannot enter.[7][5]

The practice of sworn virginhood was first reported by missionaries, travellers, geographers and anthropologists who visited the mountains of northern Albania in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[8]

Overview

A woman becomes a sworn virgin by swearing an irrevocable oath, in front of 12 village or tribal elders, to practice celibacy. Then she is allowed to live as a man. She will then be able to dress in male clothes, use a male name, carry a gun, smoke, drink alcohol, take on male work, act as the head of a household (for example, living with a sister or mother), play music and sing, and sit and talk socially with men.[7][8][9]

A woman can become a sworn virgin at any age, either to satisfy her parents or herself.[10]

The sworn virgin is believed to be the only formal, socially defined female-to-male cross-gender and cross-dressing role in Europe. Similar practices occur in some native American tribes in North America.[8]

Breaking the vow was once punishable by death, but it is doubtful that this punishment is still carried out now.[7] Many sworn virgins today still refuse to go back on their oath because their community would reject them for breaking the vows.[7] However it is sometimes possible to take back the vows if the sworn virgin has finished her obligations to the family and the reasons/motivations (see below) which enabled her to take the vows are no longer current.

Motivations

There are many reasons why a woman would have wanted to take this vow, and observers have recorded a variety of motivations. One woman said she became a sworn virgin in order to not be separated from her father, and another in order to live and work with her sister. Several were recorded as saying they always felt more male than female. Some hoped to avoid a specific unwanted marriage, and others hoped to avoid marriage in general.

Becoming a sworn virgin was the only way for women whose families had committed them as children to an arranged marriage to refuse to fulfil it, without dishonouring the groom's family and risking a blood feud. It was the only way a woman could inherit her family's wealth, which was particularly important in a society in which blood feuds resulted in the deaths of many male Albanians, leaving many families without male heirs. (However, anthropologist Mildred Dickemann suggests this motive may be "over-pat", pointing out that a non-child-bearing woman would have no heirs to inherit after her, and also that in some families not one but several daughters became sworn virgins, and in others the later birth of a brother did not end the sworn virgin's masculine role.[9]) It is also likely that many women chose to become sworn virgins simply because it afforded them much more freedom than would otherwise have been available in a patrilineal culture in which women were secluded, sex-segregated, required to be virgins before marriage and faithful afterwards, betrothed as children and married by sale without their consent, continually bearing and raising children, constantly physically labouring, and always required to defer to men, particularly their husbands and fathers, and submit to being beaten.[5][8][9][11]

Sworn virgins could also participate in blood feuds. If a sworn virgin was killed in a blood feud her death counted as a full life for the purposes of calculating blood money, rather than the half a life ordinarily accorded for a female death.[12]

Dickemann suggests their mothers may have played an important role in persuading women to become sworn virgins. A widow without sons has traditionally had few options in Albania: she could return to her birth family, stay on as a servant in the family of her deceased husband, or remarry. With a son or surrogate son, she could live out her life in the home of her adulthood, in the company of her child. Murray quotes testimony recorded by René Gremaux: "Because if you get married I'll be left alone, but if you stay with me, I'll have a son." On hearing those words Djurdja [the daughter] "threw down her embroidery" and became a man.[9]

Prevalence

The practice has died out in Dalmatia and Bosnia, but is still carried out in northern Albania and to a lesser extent in Macedonia.[8]

The Socialist People's Republic of Albania did not encourage women to become sworn virgins. Women started gaining rights, coming closer to equaling men in social status. By the time the Soviet bloc fell from Albania, women had as many rights as men, especially in the central and southern regions. It is only in the northern region that many families still live within the traditional patriarchal way.[13] Currently there are between forty and several hundred sworn virgins left in Albania, and a few in neighboring countries. Most are over fifty years old.[5] It used to be believed that the sworn virgins had all but died out after 50 years of Communism in Albania, but recent research suggests that may not be the case,[8] instead suggesting that the current increase in feuding following the collapse of the Communist regime could encourage a resurgence of the practice.[9]

Notes

- ^ Whitaker, (1984) p. 146

- ^ Shaw (2005) p. 74

- ^ Young, Antonia (December 2010). ""Sworn Virgins": The case of socially accepted gender change". Anthropology of East Europe Review.

- ^ From Turkish Kanun, which means law. It is originally derived from the Greek kanôn / κανών as in Canon Law)

- ^ a b c d Elena Becatoros (10/06/2008 12:37:38 PM MDT). "Tradition of sworn virgins' dying out in Albania". Die Welt. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Crossing Boundaries:Albania's sworn virgins". jolique. 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Joshua Zumbrun (August 11, 2007). "The Sacrifices of Albania's 'Sworn Virgins'". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical dictionary of Albania (2nd ed. ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 435. ISBN 0810861887.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e Murray, By Stephen O.; a.o, Will Roscoe; With additional contributions by Eric Allyn (1997). Islamic homosexualities: Culture, history, and literature. New York: New York University Press. p. 198. ISBN 0814774687.

- ^ Magrini, edited by Tullia (2003). Music and gender: perspectives from the Mediterranean. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 294. ISBN 0226501655.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ David Wolman (January 6, 2008). "'Sworn virgins' dying out as Albanian girls reject manly role". London: TimesOnline. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Swenson, edited by Sarah M. Anderson with Karen (2002). Cold counsel: women in Old Norse literature and mythology : a collection of essays. New York: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0815319665.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "At home with Albania's last sworn virgins". Sydney Morning Herald. June 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

References

- Shaw; Ardener, Shirley; Littlewood, Roland; Young, Antonia (2005). "The Third Sex in Albania: An Ethnographic Note". Changing Sex and Bending Gender. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-84545-053-1.

- Whitaker, Ian (2007). A Sack for Carrying Things: The Traditional Role of Women in Northern Albanian Society. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. JSTOR 3317892.

External links

- Photographs by Jill Peters, 2012

- Photographs by Johan Spanner, New York Times, 2008

- Photographs by Pepa Hristova, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie, 2009

- BBC radio show on sworn virgins

- Sworn Virgins - National Geographic Film (approx. 4 min.)

- BBC From Our Own Correspondent 02/09