Alexander Jackson Davis

Alexander Jackson Davis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 24, 1803 New York City |

| Died | January 14, 1892 (aged 88) Llewellyn Park, New Jersey |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

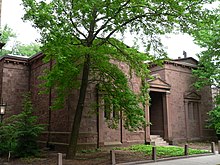

| Buildings | U.S. Customs House, Manhattan, 1833–42 (with Ithiel Town)

|

Alexander Jackson Davis, or A. J. Davis (July 24, 1803 – January 14, 1892), was one of the most successful and influential American architects of his generation, known particularly for his association with the Gothic Revival style.

Davis was born in New York City to Cornelius Davis, a bookseller and editor of theological works, and Julia Jackson. He spent his early years in New Jersey and attended elementary school in upstate New York. In 1818, Davis went to Alexandria, Virginia, to learn the printing trade from a half-brother. Living mostly in New York City from 1823 onward, he studied at the American Academy of Fine Arts,[1] the New-York Drawing Association, and from the Antique casts of the National Academy of Design. Dropping out of school, he became a respectable lithographer and from 1826 he worked as a draftsman for Josiah R. Brady, a New York architect who was an early exponent of the Gothic revival style: Brady's Gothic 1824 St. Luke's Episcopal Church is the oldest surviving structure in Rochester, New York.[2]

Career

Partnership with Ithiel Town

Davis made a first independent career as an architectural illustrator in the 1820s,[1] but his friends, especially painter John Trumbull, convinced him to turn his hand to designing buildings. Picturesque siting, massing and contrasts remained essential to his work, even when he was building in a Classical style. In 1826, Davis went to work in the office of Ithiel Town and Martin E. Thompson, the most prestigious architectural firm of the Greek Revival; in the office Davis had access to the best architectural library in the country, in a congenial atmosphere where he gained a thorough grounding.

From 1829, in partnership with Town, Davis formed the first recognizably modern architectural office and designed many late Classical buildings, including some of public prominence. In Washington, Davis designed the Executive Department offices and with Robert Mills the first Patent Office building (1834–36). [citation needed] He also designed the Custom House of New York City (1833–42). Bridgeport City Hall, constructed in 1853 and 1854, is a later government building Davis designed in the Classical style.

A series of consultations over state capitols followed, none apparently built entirely as Davis planned: the Indiana State House,[1] Indianapolis (1831 – 35), elicited calls for his advice and designs in building other state capitols in the 1830s: North Carolina's (1833 – 40, with local architect David Paton),[1] the Illinois State Capitol,[1] often attributed entirely to the Springfield, Illinois architect John F. Rague, who was at work on the Iowa State Capitol at the same time, and in 1839, the committee responsible for commissioning a design for the Ohio Statehouse asked his advice. The resulting capitol in Columbus, Ohio, often attributed to the Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole consulting with Davis and Ithiel Town,[3] has a stark Greek Doric order colonnade across a recessed entrance, flanked by recessed window bays that continue the rhythm of the central portico, all under a unique drum capped by a low saucer dome. With Town's partner James Dakin, he designed the noble colossal Corinthian order of the Greek Revival "Colonnade Row" on New York's Lafayette Street, the very first apartments designed for the prosperous American middle class (1833, half still standing). He continued in partnership with Town until shortly before Town's death in 1844.

In 1831, he was elected an associate member of the National Academy. From 1835, Davis began work on his own on Rural Residences, his only publication, the first pattern book for picturesque residences in a domesticated Gothic Revival taste, which could be executed in carpentry, and also containing the first of the Italianate style "Tuscan" villas, flat-roofed with wide overhanging eaves and picturesque corner towers. Unfortunately the Panic of 1837 cut short his plans for a series of like volumes, but Davis soon formed a partnership with Andrew Jackson Downing, illustrating his widely read books. Additions to Vesper Cliff were built in 1834.[4]

Country residences (1840 - 1860)

The 1840s and 1850s were Davis's two most fruitful decades as a designer of country houses. His villa "Lyndhurst" at Tarrytown, New York, is his single most famous house. Many of his villas were built in the scenic Hudson River Valley— where his style informed the vernacular Hudson River Bracketed that gave Edith Wharton a title for a novel [5]—but Davis sent plans and specifications to clients as far afield as Indiana, with the understanding that construction would be undertaken by local builders. The village of Skaneateles, New York, has at least two buildings designed by Davis. This practice put Davis's personal stamp on the practical builders' vernacular throughout the Eastern United States as far south as North Carolina, where he designed Blandwood, the 1846 home of Governor John Motley Morehead that stands as America's earliest Italianate Tuscan Villa. Innovative interior features, including his designs for mantels and sideboards, were also widely imitated in the trade. Other influential interior details include pocket shutters at windows, bay windows, and mirrored surfaces to reflect natural light. The Greek Revival style William Walsh House was built at Albany, New York, and Gothic Revival style Belmead was built near Powhatan, Virginia, in 1845.[6]

Two smaller but well known structures designed by Davis include one built for John Cox Stevens in 1845; Stevens was the first Commodore of New York Yacht Club and the small Carpenter Gothic building on his property near Hoboken was given to NYYC to be used as its first clubhouse. This building, fondly called "Station 10", still exists and can be found in Newport. Davis built a similar pavilion for his colleague and fellow NYYC founder, John Clarkson Jay, on Jay's Long Island Sound waterfront property in Rye, New York, in 1849. Although this building was taken down in the 1950s, the original setting and garden where it was once located is part of a National Historic Landmark site and open to the public.

In 1851, Davis completed Winyah Park, one of approximately eighteen or more Italianate houses he designed in the 1850s. Winyah was built for Richard Lathers, who had studied architecture with Davis in New York in the 1830s. It was situated on Lathers's estate in the town of New Rochelle in Westchester County, New York. For this design Davis won the first architectural prize at the New York World's Fair of 1853–54.[7][8] Davis himself must have been pleased with Winyah because he used its most striking feature, two adjacent yet contrasting towers, in a much larger house named Grace Hill, built in Brooklyn between 1853 and 1854. In both Winyah and Grace Hill, broad octagonal towers serve as visual anchors for the taller square towers. Lathers later employed Davis to design four additional "investment houses" on his property which became known as "Lathers's Hill". The homes included two Gothic cottages and "Tudor Villa" constructed in 1858, and "Pointed Villa" constructed in 1859. In 1890, the artist Frederic Remington purchased one of these cottages from which he created his estate "Endion", which served as the studio for most of his artistic career.[9] The success of "Winyah Park" and "Lathers's Hill" generated other important commissions for Davis in New Rochelle, including two cottage-villas, Wildcliff and Sans Souci, which he designed for members of a prominent Davenport family. Both homes feature Davis's signature central gable. Another extant Gothic Revival commission is Whitby Castle, designed in 1852 for Davis' lifelong friend William Chapman. The building is part of the Boston Post Road Historic District (Rye, New York) and retains many original features.

Davis was invited to become a member of the American Institute of Architects shortly after its founding in 1857.[10] In the late 1850s, Davis worked with the entrepreneur Llewellyn S. Haskell to create Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey, a garden suburb that was one of the first planned residential communities in the United States.[11]

Davis designed buildings for the University of Michigan in 1838, and in the 1840s he designed buildings for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. At Virginia Military Institute, Jackson's designs from 1848 through the 1850s created the first entirely Gothic revival college campus, built in brick and stuccoed to imitate stone.[12] Davis's plan for the Barracks quadrangle was interrupted by the Civil War; it was sympathetically completed to designs of Bertram Goodhue in the early 20th century.[13]

Declining patronage and retirement (1860 - 1892)

With the onset of Civil War in 1861, patronage in house building dried up, and after the war, new styles unsympathetic to Davis's nature were in vogue. In 1867, he designed the Hurst-Pierrepont Estate.[14] In 1878, Davis closed his office, where he had usually both lived and worked. He built little in the last thirty years of his life, but spent his easy retirement in West Orange drawing plans for grandiose schemes that he never expected to build, and selecting and ordering his designs and papers, by which he determined to be remembered. They are shared by four New York institutions: the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, the New York Public Library, the New-York Historical Society, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A further collection of Davis material has been assembled at the Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum library. After closing his office he joined his wife, Margaret Beale, whom he had married in 1853, and their two children. "Wildmont," his summer lodge overlooking Llewellyn Park, West Orange, New Jersey, was enlarged for year-round use, but it burned down in 1884, before the family could move there, and he died in a small house on its site. Davis is interred in Bloomfield Cemetery in Bloomfield, New Jersey.[15]

Legacy

Innovative and influential, Davis was a leader in bringing American architecture into the modern period, freeing it from past limitations and opening it to new forms and styles. He introduced styles new to America and invented the American Bracketed style. His designs broke open the boxlike American house form, with projections extending in every direction, bay and oriel windows reaching out, and verandas linking the house with the surrounding landscape. His interior planning was often unusual, moving toward open floor plans and space flow. Tempered by classical rationalism, Davis worked in the Romantic spirit of his day, with a deep love of nature that harmonized architecture and landscape, but his designs looked into the future. More recent interest in Davis was spurred by a retrospective exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in 1992.

See also

- John Henry Devereux, South Carolina architect who shared a client with Alexander Jackson Davis

References

- ^ a b c d e "United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.: East Front Elevation, Rendering". World Digital Library. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "Monroe County (NY) Library System - Pathfinders - Architecture - Every Building Tells a Story". www.rochester.lib.ny.us. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Images of Ohio State House, Columbus, Ohio, by Alexander Jackson Davis". www.bluffton.edu. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ William E. Krattinger (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Vesper Cliff". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2009-11-20. See also: "Accompanying 15 photos".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2005-06-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Society, South Carolina Historical (28 March 2018). "This discursive biographical sketch of Colonel Richard Lathers, 1841-1902: was compiled as required for honorary membership in Post 509, Grand Army of the Republic ..." J.B. Lippincott. Retrieved 28 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Edwards, Lee M., et al. (1986). Domestic Bliss: Family Life in American Painting, 1840-1910, p. 38. The Hudson River Museum.

- ^ Study of a New York Suburb - New Rochelle, Architectural Record 1909

- ^ "History of The American Institute of Architects". American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ W. Hawkins Ferry (1968). The Buildings of Detroit A History. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1665-8.

- ^ Mary Ann Sullivan, Clayton Hall, Virginia Military Institute Barracks

- ^ "Barracks History Timeline - VMI Archives - Virginia Military Institute". www.vmi.edu. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Elise M. Barry (April 1982). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Hurst-Pierrepont Estate". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alexander Jackson Davis, Find A Grave. Accessed August 22, 2007.

External links

- Alexander Jackson Davis architectural drawings and papers, circa 1804-1900.Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- Art and the empire city: New York, 1825-1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Davis (see index)

- Peck, Amelia, “Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History."

- John Thorn, "Alexander Jackson Davis : picturesque American"

- A.J. Davis at the Virginia Military Institute: plans and elevations at VMI

- Great Buildings on-line: Town and Davis

- Blandwood Mansion Greensboro, NC

- Driving map of Davis structures in the Hudson Valley

- Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on A.J. Davis.

- The Alexander Jackson Davis Architectural Drawing Collection at the New York Historical Society

Further reading

- Davies, Jane B (2000). Alexander Jackson Davis American National Biography. American Council of Learned Societies.

- Peck, Amelia (1992). Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect 1803-1892. Rizzoli.

- Peck, Amelia. “Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/davs/hd_davs.htm (October 2004)

- Placek, Adolf K., editor (1982). Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-925000-5.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Aspirations for Excellence : Alexander Jackson Davis and the First Campus Plan for the University of Michigan, 1838

- Great Houses of the Hudson River, Michael Middleton Dwyer, editor, with preface by Mark Rockefeller, Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, published in association with Historic Hudson Valley, 2001. ISBN 082122767X.