All's Well That Ends Well: Difference between revisions

m replace html ndash with unicode |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

*King of France |

*King of France |

||

*Duke of [[Florence]] |

*Duke of [[Florence]] |

||

*Bertram, Count of [[Roussillon| |

*Bertram, Count of [[Roussillon|Roussillon]] |

||

*Countess of |

*Countess of Roussillon, Mother to Bertram |

||

*Lavatch, a [[Clown]] in her household |

*Lavatch, a [[Clown]] in her household |

||

*Helena, a [[Gentlewoman]] protected by the Countess{{0|000}} |

*Helena, a [[Gentlewoman]] protected by the Countess{{0|000}} |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

*An Old Widow of Florence, surnamed Capilet |

*An Old Widow of Florence, surnamed Capilet |

||

*Diana, Daughter to the Widow |

*Diana, Daughter to the Widow |

||

*Steward to the Countess of |

*Steward to the Countess of Roussillon |

||

*Violenta and Mariana, Neighbours and Friends to the Widow |

*Violenta and Mariana, Neighbours and Friends to the Widow |

||

*A Page |

*A Page |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==Synopsis== |

==Synopsis== |

||

Helena, a lowborn beauty, serves as a gentlewoman in the household of the Countess of |

Helena, a lowborn beauty, serves as a gentlewoman in the household of the Countess of Roussillon. Bertram, the Countess's son, is making preparations to leave for Paris to become a ward of the King of France. Helena has long nursed a secret love for Bertram, despite their class differences. It is revealed that the King is terminally ill of a [[fistula]] (to Shakespeare it was a long pipelike ulcer). Helena, whose father was a well-renowned physician, offers to cure him if he will allow her to marry the Lord of her choice – he agrees. Her medicinal knowledge proves fruitful, and she saves the King's life. The King is overjoyed and accedes to her condition, after which she chooses the reluctant and unwilling Bertram. She offers him freedom to deny her, but the King insists on the marriage as a reward to Helena. After their wedding, Bertram decides he would rather face death in battle than remain married to Helena. He resolves to leave and fight in the Italian war developing between the [[Florence|Florentines]] and the [[Siena|Senoys]]. While at war, he writes dismissively home to Helena:{{Quote|When thou canst get the ring upon my finger, which never shall come off, and show me a child begotten of thy body that I am father to, then call me husband.|(III.ii.55–58)}} |

||

Bertram thinks these things are impossible tasks. Nevertheless, Helena sets out with a plan to recover her husband. |

Bertram thinks these things are impossible tasks. Nevertheless, Helena sets out with a plan to recover her husband. |

||

Back at the war front, the young lords strive to convince Bertram that his ne'er-do-well friend Parolles is a coward. They set up an elaborate ruse to convince Parolles to recover a company drum stolen by the enemy and trick him into believing he has been captured. Parolles, thinking himself begging for his life, readily spills all his army's secrets to his "captors", betraying Bertram ("a foolish idle boy, and for all that very ruttish") in the process. Dishonored and stripped of his title, Parolles returns to France as a beggar. Helena, meanwhile, enlists the aid of Diana, a maiden who has taken Bertram's fancy. Together they execute the bait-and-switch "[[bed trick]]" during which Helena successfully gets the |

Back at the war front, the young lords strive to convince Bertram that his ne'er-do-well friend Parolles is a coward. They set up an elaborate ruse to convince Parolles to recover a company drum stolen by the enemy and trick him into believing he has been captured. Parolles, thinking himself begging for his life, readily spills all his army's secrets to his "captors", betraying Bertram ("a foolish idle boy, and for all that very ruttish") in the process. Dishonored and stripped of his title, Parolles returns to France as a beggar. Helena, meanwhile, enlists the aid of Diana, a maiden who has taken Bertram's fancy. Together they execute the bait-and-switch "[[bed trick]]" during which Helena successfully gets the Roussillon family ring and sleeps with Bertram as per the conditions in his letter. In the final act, Helena's cunning plot is revealed, and Bertram promises to be a faithful husband to her and "love her dearly, ever, ever dearly". (V.iii.354) |

||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

Revision as of 12:30, 23 January 2010

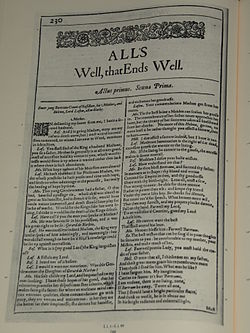

All's Well That Ends Well is a play by William Shakespeare. It is believed to have been written between 1601 and 1608,[1] and it was first published in the First Folio in 1623.

Though originally the play was classified as a comedy, the play is now considered by some critics to be one of his problem plays, so named because they cannot be neatly classified as tragedy or comedy.

Characters

|

|

Synopsis

Helena, a lowborn beauty, serves as a gentlewoman in the household of the Countess of Roussillon. Bertram, the Countess's son, is making preparations to leave for Paris to become a ward of the King of France. Helena has long nursed a secret love for Bertram, despite their class differences. It is revealed that the King is terminally ill of a fistula (to Shakespeare it was a long pipelike ulcer). Helena, whose father was a well-renowned physician, offers to cure him if he will allow her to marry the Lord of her choice – he agrees. Her medicinal knowledge proves fruitful, and she saves the King's life. The King is overjoyed and accedes to her condition, after which she chooses the reluctant and unwilling Bertram. She offers him freedom to deny her, but the King insists on the marriage as a reward to Helena. After their wedding, Bertram decides he would rather face death in battle than remain married to Helena. He resolves to leave and fight in the Italian war developing between the Florentines and the Senoys. While at war, he writes dismissively home to Helena:

When thou canst get the ring upon my finger, which never shall come off, and show me a child begotten of thy body that I am father to, then call me husband.

— (III.ii.55–58)

Bertram thinks these things are impossible tasks. Nevertheless, Helena sets out with a plan to recover her husband.

Back at the war front, the young lords strive to convince Bertram that his ne'er-do-well friend Parolles is a coward. They set up an elaborate ruse to convince Parolles to recover a company drum stolen by the enemy and trick him into believing he has been captured. Parolles, thinking himself begging for his life, readily spills all his army's secrets to his "captors", betraying Bertram ("a foolish idle boy, and for all that very ruttish") in the process. Dishonored and stripped of his title, Parolles returns to France as a beggar. Helena, meanwhile, enlists the aid of Diana, a maiden who has taken Bertram's fancy. Together they execute the bait-and-switch "bed trick" during which Helena successfully gets the Roussillon family ring and sleeps with Bertram as per the conditions in his letter. In the final act, Helena's cunning plot is revealed, and Bertram promises to be a faithful husband to her and "love her dearly, ever, ever dearly". (V.iii.354)

Sources

The play is based on a tale (3.9) of Boccaccio's The Decameron. Shakespeare may have read an English translation of the tale in William Painter's Palace of Pleasure.[2]

The name of the play comes from the proverb All's well that ends well, which means that problems do not matter so long as the outcome is good.[3]

Performance history

There are no recorded performances before the Restoration; the earliest occurred in 1741 at Goodman's Fields, with another the following year at Drury Lane where it acquired its reputation of being an unlucky play. The actress playing Helena, Peg Woffington fainted and had to be replaced, while the actor playing the King of France subsequently died. Henry Woodward popularised the part of Parolles in the Garrick era. Sporadic performances followed in the ensuing decades, with an operatic version at Covent Garden in 1832. George Bernard Shaw greatly admired Helena's character, comparing her with the New Woman figures such as Nora in Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House.[4]

Victorian objections centred on the character of Helena, who was variously deemed predatory, immodest and both "really despicable" and a "doormat" by Ellen Terry, who also – and rather contradictorily – accused her of "hunt[ing] men down in the most undignified way". In 1896 Frederick S. Boas coined the term "problem play" to include the unpopular work, grouping it with Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida and Measure for Measure.[5]

Critical comment

There is no evidence that All's Well was popular in Shakespeare's own lifetime, and it has remained one of his lesser-known plays ever since, in part due to its odd mixture of fairy tale logic and cynical realism. Helena's love for the seemingly unlovable Bertram is difficult to explain on the page, but in performance it can be made acceptable by casting an actor of obvious physical attraction as Bertram, or by playing him as a naive and innocent figure not yet ready for love although, as both Helena and the audience can see, capable of emotional growth.[6] This latter interpretation also assists at the point in the final scene in which Bertram suddenly switches from hatred to love in just one line. This is considered a particular problem for actors trained to admire psychological realism. However, some alternative readings emphasise the "if" in his equivocal promise: "If she, my liege, can make me know this clearly, I'll love her dearly, ever, ever dearly." Here, there has been no change of heart at all.[4]

One character that has been admired is that of the old Countess, which Shaw thought "the most beautiful old woman's part ever written".[4] Modern productions are often promoted as vehicles for great mature actresses; recent examples have starred Judi Dench and Peggy Ashcroft, who delivered a performance of "entranc[ing]...worldly wisdom and compassion" in Trevor Nunn's sympathetic, "Chekhovian" staging at Stratford in 1982.[4][7][8]

References

- ^ Snyder, Susan (1993). "Introduction". The Oxford Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 20–24. ISBN 9780192836045.

- ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 29.

- ^ The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, 3rd ed., 2002. Cited atBartleby.com

- ^ a b c d Dickson, Andrew (2008). "All's Well That Ends Well". The Rough Guide to Shakespeare. London: Penguin. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-1-85828-443-9.

- ^ Neely, Carol Thomas (1983). "Power and Viginity in the Problem Comedies: All's Well That Ends Well". Broken nuptials in Shakespeare's plays. New Haven, CT: University of Yale Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780300033410.

- ^ McCandless, David (1997). "All's Well That Ends Well". Gender and performance in Shakespeare's problem comedies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-253-33306-7.

- ^ Kellaway, Kate (14 December 2003). "Judi...and the beast". The Observer. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Billington, Michael (2001). One Night Stands: a Critic's View of Modern British Theatre (2 ed.). London: Nick Hern Books. pp. 174–176. ISBN 1-854-59660-8.

External links

- MaximumEdge.com Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well – searchable scene-indexed version of the play.

- Photos of a production of All's Well That Ends Well