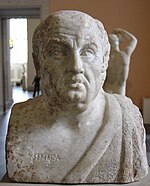

Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus

Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus | |

|---|---|

| Suffect consul of the Roman Empire | |

| In office 51–52 Serving with Titus Cutius Ciltus | |

| Preceded by | Quintus Volusius Saturninu Publius Cornelius Scipio |

| Succeeded by | Publius Sulpicius Scribonius Rufus Publius Sulpicius Scribonius Proculus |

Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus or Gallio (Greek: Γαλλιων, Galliōn; c. 5 BC – c. AD 65) was a Roman senator and brother of the famous writer Seneca. He is best known for dismissing an accusation brought against Paul the Apostle in Corinth.

Life

[edit]Gallio (originally named Lucius Annaeus Novatus), the son of the rhetorician Seneca the Elder and the elder brother of Seneca the Younger, was born in Corduba (Cordova) c. 5 BC. He was adopted by Lucius Junius Gallio, a rhetorician of some repute, from whom he took the name of Junius Gallio. His brother Seneca, who dedicated to him the treatises De Ira and De Vita Beata, speaks of the charm of his disposition, also alluded to by the poet Statius (Silvae, ii.7, 32). It is probable that he was banished to Corsica with his brother, and that they returned together to Rome when Agrippina selected Seneca to be tutor to Nero. Towards the close of the reign of Claudius, Gallio was proconsul of the newly constituted senatorial province of Achaea, but seems to have been compelled by ill-health to resign the post within a few years. He was referred to by Claudius as "my friend and proconsul" in the Delphi Inscription, around 52.

Gallio was a suffect or replacement consul in the mid-50s,[1] and Cassius Dio records that he introduced Nero's performances.[2] Not long after the death of his brother, Seneca, Gallio (according to Tacitus, Ann. 15.73) was attacked in the Senate by Salienus Clemens, who accused him of being a "parricide and public enemy", though the Senate unanimously appealed to Salienus not to profit "from public misfortunes to satisfy a private animosity".[3] He did not survive this reprieve long. When his second brother, Annaeus Mela, opened his veins after being accused of involvement in a conspiracy (Tacitus, Ann. 16.17), Gallio seems to have committed suicide, perhaps under instruction in 65 AD.[4]

Gallio and Paul the Apostle

[edit]According to the Acts of the Apostles, when Gallio was proconsul of Achaea, Paul the Apostle was brought in front of him by the Jews of Corinth with the accusation of having violated Mosaic Law. This action was presumably headed by Sosthenes, a ruler of the local synagogue. Gallio, however, was indifferent towards religious disputes between the Jews and Jewish Christians; therefore, he dismissed the charges against Paul (denegatio actionis) and had both him and the Jews removed from the Court. As this was being done, Sosthenes was beaten, but Gallio did not intervene (Acts 18:12-17).

Gallio's tenure can be fairly accurately dated to between AD 51–52.[5] Therefore, the events of Acts 18 can be dated to this period. This is significant because it is the most accurately known date in the life of Paul.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "L. Junius Annaeus Gallio, was suffect consul in the mid-50s AD, perhaps in 54." Robert C. Knapp, Roman Córdoba (University of California Press, 1992) ISBN 9780520096769 p.42. "L. Junius Gallio did hold consulship in 55 or 56". Anthony Barrett, Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Empire (Routledge, 1999) ISBN 9780415208673 p.280. "Gallio reached the consulship, probably in 55". Miriam T. Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty (Routledge, 1987) ISBN 0415214645 p.78. E. Mary Smallwood, "Consules Suffecti of A.D. 55", in Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Bd. 17, H. 3 (Jul., 1968), p. 384.

- ^ Miriam T. Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty (Routledge, 1987) ISBN 0415214645 p.45, relying on Dio 61.20, 2-3.

- ^ Vasily Rudich, Political Dissidence Under Nero: The Price of Dissimulation (Routledge, 1993) ISBN 9780415069519 p.117. And Steven Rutledge, Imperial Inquisitions: Prosecutors and Informants from Tiberius to Domitian (Routledge, 2001) ISBN 9780415237000 p.169.

- ^ Vasily Rudich, Political Dissidence Under Nero: The Price of Dissimulation (Routledge, 1993) ISBN 9780415069519 p.117.

- ^ John Drane, "An Introduction to the Bible", Lion, 1990, p. 634-635

- ^ Pauline Chronology: His Life and Missionary Work, from Catholic Resources by Felix Just, S.J.

Resources

[edit]- Ancient sources: Tacitus, Annals, xv.73; Dio Cassius, lx.35, lxii.25.

- Bruce Winter, "Rehabilitating Gallio and his Judgement in Acts 18:14-15", Tyndale Bulletin 57.2 (2006) 291–308.

- Sir W. M. Ramsay, St Paul the Traveller, pp. 257–261

- Cowan, H. (1899). "Gallio". In James Hastings (ed.). A Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. II. pp. 105–106.

- An interesting reconstruction is given by Anatole France in Sur la pierre blanche.

- F. L. Lucas's story “The Hydra (A.D. 53)” in The Woman Clothed with the Sun, and other stories (Cassell, London, 1937; Simon & Schuster, N.Y., 1938) focuses on Gallio at the time of Paul's trial. "A Greek trader, a chance acquaintance of Judas Iscariot, comes to tell the Roman Governor of Corinth 'the real truth about this religious quarrel among the Jews', but is dissuaded by the tolerant old man from taking risks for Truth" (Time and Tide, August 14, 1937).

- Rudyard Kipling's Gallio's Song

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gallio, Junius Annaeus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 419.

External links

[edit]- Gallio at Bible Study

- Paul's Trial Before Gallio A summary of the historical evidence.

- The Gallio Inscription Greek text and English translation.