Anointing

To anoint is to pour or smear with perfumed oil, milk, water, melted butter or other substances, a process employed ritually by many religions. People and things are anointed to symbolize the introduction of a sacramental or divine influence, a holy emanation, spirit, power or God.[1] It can also be seen as a spiritual mode of ridding persons and things of dangerous influences, as of demons (Persian drug, Greek κηρες Keres, Armenian dev) believed to be or to cause disease.

Unction is another term for anointing. The oil may be called chrism.

The word is known in English since c. 1303, deriving from Old French enoint "smeared on", pp. of enoindre "smear on", itself from Latin inunguere, from in- "on" + unguere "to smear." Originally it only referred to grease or oil smeared on for medicinal purposes; its use in the Coverdale Bible in reference to Christ (cf. The Lord's Anointed, see Chrism) has spiritualized the sense of it, a sense expanded and expounded upon by St Paul's writings in his "Epistles". The title Christ is derived from the Greek term Χριστός (Khristós) meaning "the anointed one"; covered in oil, anointed, itself from the above mentioned word Keres.

Eastern tradition

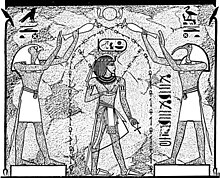

A complex of late Vedic and Buddhist rituals involved the anointing of government officials, worshipers, or statues and images of deities, in a rite called Abhisheka. Abhishekionians had believed that the virtues of one killed could be transferred to survivors if the latter rubbed themselves with his caul-fat. Other rites are associated with eating a victim whose virtues are coveted. So the Arabs of East Africa anoint themselves with lion's fat in order to gain courage and inspire fear in other animals. Human fat is likewise a powerful charm. W. Robertson Smith points out,[citation needed] after the blood, fat was peculiarly the vehicle and seat of life.[2] This is why fat of a victim was smeared on a sacred stone, not only in homage but in consecration. The influence of the deity, communicated to the victim, passed with the unguent into the stone. Thus such divinity could, by anointing, be transferred into men as well. In several temple reliefs in Ancient Egypt the Pharaoh is depicted being anointed by Horus (sun god and "father" of Pharaoh) and Thoth (god of wisdom), the oil of which is symbolically depicted as a stream of ankhs (symbols of life). Also, especially from the New Kingdom onward, anointing is often depicted in intimate scenes between husband and wife, where the wife is shown anointing her spouse, as a sign of affection. The most famous example of this is on the throne of Tutankhamun.

Most famously in Pharaonic Egypt—along with many other ancient cultures—preparation for burial included anointing human remains with sweet-smelling oils in devotion as well with the practical intent of obscuring the stench of death.[3] In sealing a coffin a ritual, final anointing of the mummy was observed.

In the Hindu belief systems anointment is freely practiced. To mark particular devotions, as a "consecration" to particular beliefs or as a ritualized blessing used especially to invoke auspicious beginnings, every stage of life features some gesture of anointment, from rituals accompanying birthing, to religious or educational initiations, royal enthronements to final rites. Even every new building and household is anointed, as well as some ritual instruments. Likewise, the installation and care of any deity's form (frequently appearing as a statue) can involve daily ritual anointing. In every case the direction of the smearing is significant. Persons are anointed from head to foot, downwards, as in India the ground is considered less clean than the uplifted head. Anointing is also used to aid persons within negative cycles—illnesses, demonic possession or streaks of "bad luck".

Though our western root word indicates a greasing of the head or skin with what is generally used as food, we understand "anointing" today to involve broader beliefs and practices, from ritual to talismanic. Yogurt, milk or butter produced by the Hindu's revered cow forms the base of much ritual anointing. Hindu ointments also include ashes, clay, wood (particularly sandal-wood) powders, herbal pastes, as well as endless waters, from sacred rivers or scented with saffron, turmeric, or flower-waters such as jasmine, gardenia, rose-water or infusions. More exotic are rinse-water used in bathing a deity and ink-water which has passed over the fresh calligraphy of appropriate scriptural verses—thus tinged with ink. Ayurvedic medicine practices include extensive herbal, mineral and talismanic preparations compounded and applied according to astrologic and Vedic prescription which tend to further expand monotheistic Western definitions of "anointment".

Buddhist practices of anointing are largely derived from Indian practices but tend to be much less free and noticeably less elaborate. The range of buddhist "anointments" typically include sprinkling assembled practitioners with water and the devotions shown to deities, images or ritual articles by marking statues of Buddhas, Bodhisatvvas and divinities with butter (including yak butter) and various waters including flower-waters, "saffron-waters" stained yellow using saffron or turmeric. Ointments including astrological and talismanic elements such as ink-water are also employed in Buddhist herbal medicine practice.

Hebrew Bible

Among the Hebrews, the act of anointing with the Holy anointing oil was significant in consecration to a holy or sacred use: hence the anointing of the high priest (Exodus 29:29; Leviticus 4:3) and of the sacred vessels (Exodus 30:26). Later, Kings and Prophets were given the right to partake in this sacrament as well.

Medicinal

Olive oil was used also for medicinal purposes. It was applied to the sick, and also to wounds to soften them (Isaiah 1:6).

The expression, "anoint the shield" (Isaiah 21:5), refers to the custom of rubbing oil on the leather of the shield so as to make it supple and fit for use in war.

Hospitality

It was the custom of the Jews in like manner to anoint themselves with oil, as a means of refreshing or invigorating their bodies (2 Samuel 14:2; Psalms 104:15, etc.). The Hellenes had similar customs. This custom is continued among the Arabs to the present day. Since about 3,000 years ago, Persian Zoroastrians honor their guests with rose extract [Golaab], while holding mirror in front of their guest's face. The guest holds his/her palm, collects the rose-water and then spreads the perfumed liquid onto face and sometimes on his/her head. The words of "Rooj kori aka" (have a nice day) might be said as well.

Priests and kings

The High Priest and the king are each sometimes called "the anointed" (Leviticus 4:3–5, 4:16; 6:20; Psalm 132:10). Prophets were also anointed with the Holy anointing oil (1 Kings 19:16; 1 Chronicles 16:22; Psalm 105:15).

Anointing a king was equivalent to crowning him; in fact, in Israel a crown was not required (1 Samuel 16:13; 2 Samuel 2:4, etc.). Thus Saul (1 Sam 10:1) and David were anointed as kings by the prophet Samuel:

- Then Samuel took the horn of oil, and anointed him in the midst of his brethren: and the Spirit of the Lord came upon David from that day forward. So Samuel rose up, and went to Ramah.—1 Samuel 16:13.

Christian Gospels

The Messiah, The Christ

Distinct from the Jewish view, Christians believe the "anointed" one referred to in various biblical verses such as Psalm 2:2, Daniel 7:13 and Daniel 9:25–26 is the promised Christian Messiah. According to the Jewish Bible, whenever someone was anointed with the specific Holy anointing oil formula and ceremony described in Exodus 30:22–25, the Spirit of God came upon this person, to qualify him or her for a God-given task. According to the New Testament, Jesus of Nazareth is this Anointed One, the Messiah (John 1:41; Acts 9:22; 17:2–3; 18:5, 18:28). Christians believe that the kings of the Old Testament were anointed with oil and only afterwards did they receive Power through the Holy Spirit that came upon them, but that Jesus on the other hand, was anointed because the Holy Spirit had come upon Him (Acts 10:38). Thus, for Christians, Jesus was anointed with the power of the Holy Spirit itself. God was pleased that Jesus should be His Son (Matthew 3:16) and Jesus was the anointed of God. For Christians, this marks a difference between the power of the kings of Israel and the power that Jesus (The King of Israel) had – the kings were anointed by a human high priest, but Jesus was anointed by God Himself. The Bible also makes a difference between Jesus Christ being anointed with the Spirit of God without measure while on earth (John 3:34) and the ascended, glorified Jesus Christ being anointed with the Spirit of God at The right hand of The Father (Acts 2:33). According to Psalm 92:10, The Old Testament psalmist called the anointing of the ascended and glorified Christ,"Fresh Oil". This "Fresh Oil" was then given to the Church on the day of Pentecost.[4] The Gospels also state that he was physically "anointed" by an anonymous woman who is interpreted by some as Mary Magdalene; however, this anointing was not done by a high priest, described in Exodus,[5] but rather done out of affection, which Jesus stated was to prepare him for his burial. The word Christ which is now used as though it were a surname was more accurately a title which was equivalent to the Hebrew HaMashiach meaning "the anointed one.”

Hospitality

Anointing was also an act of hospitality, as Jesus was anointed in the house of the Pharisee (Luke 7:38–46).

Medicinal

The New Testament records that oil was applied to the sick, and also to wounds Mark 6:13; James 5:14.

The bodies of the dead were sometimes anointed (Mark 14:8; Luke 23:56).

Christian monarchy

In Christian Europe, the Carolingian monarchy was the first to anoint the king [6] in the 7th century AD at a coronation ceremony that was designed to epitomize the Catholic Church's conferring a religious sanction of the monarch's divine right to rule. Nevertheless, a number of Merovingian, Carolingian and Ottonian kings and emperors have avoided coronation and anointing.

English and Scottish monarchs in common with the French included anointing in the coronation rituals (sacre in French). Today, only the Monarch of the United Kingdom and the Monarch of Tonga are crowned and anointed. For the coronation of King Charles I in 1626 the holy oil was made of a concoction of orange, jasmine, distilled roses, distilled cinnamon, oil of ben, extract of bensoint, ambergris, musk and civet.

Shakespeare reflected English popular culture in the indelible nature of anointing:

Not all the water in the rough rude sea

Can wash the balm off an anointed king.[7]

However this does not symbolize any subordination to the religious authority, hence it is not usually performed in Catholic monarchies by the Pope but usually reserved for the (arch)bishop of a major see (sometimes the site of the whole coronation) in the nation (usually its primate), as is sometime the very act of crowning. Hence its utensils can be part of the regalia, such as in the French kingdom an ampulla for the oil and a spoon to apply it with; in the Swedish and Norwegian kingdoms, an anointing horn (a form fitting the Biblical as well as the Viking tradition) is the traditional vessel.

The French Kings adopted the fleur-de-lis as a baptismal symbol of purity on the conversion of the Frankish King Clovis I to the Christian religion in 493. To further enhance its mystique, a legend eventually sprang up that a vial of oil—the Holy Ampulla—descended from Heaven to anoint and sanctify Clovis as King. The thus "anointed" Kings of France later maintained that their authority was directly from God, without the mediation of either the Emperor or the Pope.

Legends claim that even the lily itself appeared at the baptismal ceremony as a gift of blessing in an apparition of the blessed Virgin Mary.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Anointing of an Orthodox Sovereign is considered a Sacred Mystery (Sacrament). The act was believed to bestow upon the ruler the empowerment, through the grace of the Holy Spirit, to discharge his God-appointed duties, and his ministry in defending the Orthodox Christian faith. The same Myron which is used in Chrismation is used for the Anointing of the Monarch. In the Russian Orthodox Church, during the Coronation of the Tsar, the Anointing took place just before the receipt of Holy Communion, toward the end of the service. The Sovereign and his Consort were escorted to the Holy Doors (Iconostasis) of the Cathedral, and were there anointed by the Metropolitan. After the Anointing, the Tsar alone was taken through the Holy Doors (an action normally reserved only for bishops or priests) and received Holy Communion at a small table set next to the Holy Table, or altar.[8]

Christian sacramental usage

Anointing in the New Testament

In early Christian times, sick people were anointed for healing to take place:

- James 5:14–15

- 14 Is any sick among you? let him call for the elders of the church; and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord:

- 15 And the prayer of faith shall save the sick, and the Lord shall raise him up; and if he have committed sins, they shall be forgiven him.

- Mark 6:13

- 13 And they cast out many devils, and anointed with oil many that were sick, and healed them.

Early Christian usage

Scholars have often supposed that anointing in early Christian initiation arose first among the Gnostics. Many early apocryphal and Gnostic texts indicate that anointing was part of the baptismal process, and in fact that the baptism with water (Johns baptism) is incomplete. The Gospel of Philip states; "The Chrism is superior to baptism, for it is from the word "Chrism" that we have been called "Christians," certainly not because of the word "baptism." And it from the "Chrism" that the "Christ" has his name. For the Father anointed the Son, and the Son anointed the apostles, and the apostles anointed us. He who has been anointed possesses everything. He possesses the Resurrection, the Light, the Cross, the Holy Spirit. The Father gave him this in the bridal chamber, he merely accepted the gift. The Father was in the Son and the Son in the Father. This is the Kingdom of Heaven." In the Acts of Thomas the anointing is in fact the beginning of the baptismal process and essential to becoming a "Christian." It claims that God knows his own children by his seal, and that we shall receive the seal by the oil. Many such baptisms/Chrismations are described in detail throughout the text.

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to suppose that anointing was adapted from Gnostic practice. In defending the name “Christian,” Theophilus of Antioch, bishop there from 169-183 A.D., in To Autolycus, appeals to anointing as “sweet and useful” (a pun on χριστóς, anointed, and χρηστóς, useful). “Wherefore we are called Christians on this account, because we are anointed with the oil of God” (To Autolycus 1.12). This reference, quite probably to early non-Gnostic practices of anointing in connection with Christian initiation, predates any of the Gnostic texts. If Theophilus uses “oil” literally here, he is the first "orthodox" writer to refer to a literal anointing when one became a Christian. [The earliest manuscript of the work reads “mercy” (ἔλεoς) instead of “oil” (ἔλαιoν), but a corrector wrote “oil,” in agreement with the other two manuscripts.] Even if his statement is literal and not figurative, Theophilus was more interested in anointing as a metaphor than as a practice per se. The practice probably developed in the second half of the second century in both orthodox and unorthodox circles. Much of the development of liturgical actions in connection with baptism gave expression in literal acts to theological ideas associated with baptism, and it was natural to bring out the association of Christians with Christ (“the Anointed One”) and the idea of being anointed with the Holy Spirit by anointing the baptized with that which symbolized the Holy Spirit, with whom Christ was anointed. Theophilus’s words in praise of oil in the same section may hint at other considerations that encouraged the practice: “What person on entering into this life or being an athlete is not anointed with oil?” The anointing of a newborn child after its first bath would have suggested an anointing of the one who received the new birth in baptism, and the anointing of an athlete for the contests would have suggested the same for those who undertook the life of God’s athlete.[9] Hippolytus of Rome devotes his Commentary on the Song of Songs to a celebration of the Christian rite of post-baptismal anointing. While certain anti-Valentinian tendencies are decernible in the commentary, it would be a mistake to assume that Hippolytus derived the practice of baptsimal anointing from the Valentinians.[10] Origen of Alexandria also refers to anointing in connection with Christian initiation in baptism. This association was in keeping with ancient practice where a bath and an anointing were essentially one act. “All of us may be baptized in those visible waters and in a visible anointing, in accordance with the form handed down to the churches” (Commentary on Romans 5.8.3).

Roman Catholic usage

The Roman Catholic Church blesses three types of holy oils for anointing: Oil of the Catechumens (traditionally abbreviated "OS" for oleum sanctum), Oil of the Infirm ("OI"), and Sacred Chrism ("SC"). The first two are said to be "blessed", while chrism is "consecrated".

The Oil of Catechumens is used to anoint the catechumens (adults preparing for reception into the church) just before receiving the Sacrament of Baptism. Anointing is part of the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick, and the Oil of the Infirm is used for this. The Sacred Chrism is used in the Sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, and Holy Orders.

Any bishop may consecrate the holy oils, and normally do so every Holy Thursday at a special "Chrism Mass".

Orthodox usage

In the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches, Confirmation is known as Chrismation—from the Greek word chrisma (χρίσμα), meaning the medium and act of anointing. The Eastern Churches perform the Mystery of Chrismation immediately after the Mystery of Baptism during the same ceremony, even in the case of infant baptism, using the sacred myron (chrism) which they believe contains a remnant of oil blessed by the Twelve Apostles. This myron may be added to as needed, usually at a ceremony held on Holy Thursday at one of the Patriarchal Cathedrals. The new myron contains olive oil, myrrh, and numerous spices and perfumes. This myron is normally kept on the Holy Table (altar) or on the Table of Oblation. During Chrismation, the newly illuminate (i.e., newly baptized) person is anointed by making the sign of the cross with the myron on the forehead, eyes, nostrils, lips, both ears, breast, hands and feet. The priest uses a special brush for this purpose.

The oil that is used to anoint the catechumens before baptism is simple olive oil which is blessed by the priest immediately before he pours it into the baptismal font. Then, using his fingers, he takes some of the blessed oil floating on the surface of the baptismal water and anoints the catechumen on the forehead, breast, shoulders, ears, hands and feet. He then immediately baptizes the catechumen with threefold immersion in the name of the Trinity.

Anointing of the sick is called the Sacred Mystery of Unction. Although practices will vary, most of the Orthodox use Unction not only for physical ailments, but for spiritual ailments as well, and the faithful may request Unction any number of times at will. In some churches, it is normal for all of the faithful to receive Unction during a service on Holy Wednesday of Holy Week. The holy oil used at Unction is not stored in the church like the myron, but consecrated anew for each individual service. When an Orthodox Christian dies, if he has received the Mystery of Unction, and some of the consecrated oil remains, it is poured over his body just before burial.

It is also common to bless using oils which have been blessed either with a simple blessing by a priest (or even a venerated monastic), or by contact with some sacred object, such as relics of a saint, or which has been taken from an oil lamp burning in front of a wonderworking icon or some other shrine.

Consecration of Oil in the Orthodox Church

Among Eastern Orthodox Churches, the Myron (Μύρον, Holy Oil) for Chrismation (and, prior to the 20th century, for the Anointing of monarchs) is prepared periodically by the Orthodox Patriarchates (such as the Church of Constantinople—see an announcement and process for preparation, with some sample dates of preparation) and by the various heads of autocephalous churches (such as the Orthodox Church in America—see photos of the process). The Consecration of the Oil, when performed, occurs during Holy Week, and thereafter the Oil is distributed to the Orthodox parishes and monasteries under the authority of that ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

At the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the process is under the care of the Archontes Myrepsoi, lay officials of the Patriarchate. Various members of the clergy may also participate in the preparation, but the Consecration itself is always performed by the Patriarch or a bishop deputed by him for that purpose.

Pentecostal churches

As in the early Christian church, anointing with oil is used in Pentecostal churches for healing the sick and also for consecration or ordination of pastors and elders.

The word "anointing" is also frequently used by Pentecostal Christians to refer to the power of God or the Spirit of God residing in a Christian: a usage that occurs from time to time in the Bible (e.g. in 1 John 2:20). A particularly popular expression is "the anointing that breaks the yoke", which is derived from Isaiah 10:27:

- And it shall come to pass on that day, that his burden shall be removed from upon your shoulder, and his yoke from upon your neck, and the yoke shall be destroyed because of oil.

The NIV translates this passage as, "the yoke will be broken because you have grown so fat." The context of this passage refers to the yoke of Sennacherib, and how his oppressive nature is overturned by that of Hezekiah who was said to be as mild as oil.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Melchizedek Priesthood holders may anoint the head of an individual who is ill and has requested a blessing. Pure olive oil must be used, and it must have been consecrated earlier in a short ordinance that any Melchizedek Priesthood holder may perform. In addition to the James 5:14–15 reference, the Doctrine and Covenants contains numerous references to the anointing and healing of the sick by those with authority to do so.

Church founder Joseph Smith instituted anointing for other purposes on 21 January 1836 as a sign of sanctification and consecration preparatory to the endowment rites practiced in the Kirtland Temple.[11]

Biblical metaphor

Anointing is not only used by Pentecostal churches but by many other denominations to describe the work of the Holy Spirit among believers. In so doing they only recognize the spiritual anointing that the Bible speaks of. But you have an anointing from the Holy One 1 John 2:20. But the anointing, which you have received from Him abides in you 1 John 2:27

See also

Further reading

- Spieckermann, Hermann. "Anointing." In The Encyclopedia of Christianity, edited by Erwin Fahlbusch and Geoffrey William Bromiley, 66. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1999. ISBN 0802824137

Notes

- ^ Graham,Pastor James "The Picture Chart of The Horn of Fresh Oil" Createspace 2013 ISBN 149423307X pg3

- ^ Lectures on the Religion of the Semites

- ^ See for example: (Mark 16:1, Luke 23:56–24:1, John 19:39–40)

- ^ Graham, Pastor James (2013) The Picture Chart of The Horn of Fresh Oil pg3 ISBN 149423307X

- ^ Fleming, Daniel (1998). "The Biblical Tradition of Anointing Priests". Journal of Biblical Literature. 117 (3): 401–414. JSTOR 3266438.

- ^ Nelson, Janet L., 'The Lord's anointed and the people's choice: Carolingian royal ritual', in: Cannadine, David & Price, Simon: Rituals of Royalty. Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies, Cambridge, et al.: Cambridge University Press, 1987, 137-180, p. 137 & 142, also: Angenendt, Arnold: 'Pippins Königserhebung und Salbung', in: Becher, Michael & Jarnut, Jörg: Der Dynastiewechsel von 751. Vorgeschichte, Legitimationsstrategien und Erinnerung, Münster: Scriptorum 2004, 179-210, pp. 179 f.

- ^ Shakespeare, Richard II, II/ii.

- ^ Coronation of the Russian monarch

- ^ Ferguson, Everett (2009). Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Kindle Locations 5142-5149: Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 269. ISBN 0802827489.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Smith, Yancy (2013). The Mystery of Anointing. Gorgias. p. 30. ISBN 1463202180.

- ^ "Anoint," The Joseph Smith Papers (accessed 24 October 2012)

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)- EtymologyOnLine - word history