Arcovenator

| Arcovenator Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

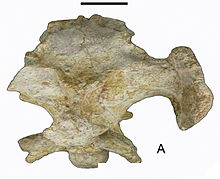

| Braincase (MHNAix-PV 2011-12) in dorsal view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Abelisauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Majungasaurinae |

| Genus: | †Arcovenator Tortosa et al., 2014 |

| Species: | †A. escotae

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Arcovenator escotae Tortosa et al., 2014

| |

Arcovenator ("Arc hunter") is an extinct genus of abelisaurid theropod dinosaurs hailing from the Late Cretaceous of France and possibly Spain.[1][2] The type and only described species is Arcovenator escotae.[1]

Description

[edit]

Though shallower, the nearly complete braincase of Arcovenator is otherwise similar in size to those of Majungasaurus and Carnotaurus; it was thus initially estimated as being about 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long,[1] but it was estimated in 2016 as being 4.8 m (16 ft) in length.[3] The skull roof exhibits as a unique diagnostic character a midline foramen, possibly housing the pineal gland, situated on the posterior surface of a slight dome formed by frontal bones as moderately thick as in Aucasaurus, thus less so than for Rajasaurus, though more than those of Rugops.[1] Less characteristically, above the orbit is a low fossa with a small fenestra bordered by the lacrimal, frontal, and postorbital.[1] The parietal bordering the supratemporal fenestrae forms ridges medially on the latter's respective anteromedial margins which, as they approach the parietal eminence, fuse into a sagittal crest.[1] The postorbital is intermediate between the plesiomorphic T-shaped condition of Eoabelisaurus and the derived inverted L-shaped one of Carnotaurus due to the unique feature of having a sheet of bone linking its ventral and posterior processes.[1] It has, in a similar autapomorphic fashion, a thick, rough-surfaced process dorsal to the eye socket that extends to the lacrimal, forming a bony brow ridge, and in a less notable way, a lateral rugose tuberosity on the extremity of its ventral process.[1] The paroccipital processes have remarkable accessory dorsal and ventral bony bars, that thus bound depressions lateral to the foramen magnum.[1] The ear region closely resembles that of Majungasaurus, though differing most substantially on a laterally directed basipterygoid process, with the shorter crista prootica and the smaller extent of a groove anterior to the 2nd and 3rd cranial nerve foramina being minor deviances from Majungasaurinae's type.[1] The squamosal is similar to that of the latter except for a less prominent parietal process.[1] Generally, the external bone ornamentation is more subdued than that of Majungasaurus.[1] The tall teeth (3-5.5 cm) have denticles on the apical portion of the mesial carina and along the length of the distal one, with varying density.[1]

The caudal vertebrae of A. escotae are remarkably similar to those of Majungasaurus, though more dorsoventrally compressed.[1] The centra possess amphicoelous articulations with the pertinent facets of an intermediate nature between the circular ones of Ilokelesia and those of the elliptical shape in Rajasaurus and have neither pneumatic recesses nor accessory hyposphene-hypantrum articulations.[1] The transverse processes of the neural arches are not as inclined as in the Brachyrostra.[1]

The cnemial crest of Arcovenator's the slender 51-cm tibia is well developed as is characteristic of abelisauroids.[1] It has a proximal lateral condyle more prominent than the medial one, a slight anterodorsal curve on the proximal aspect of the fibular crest, a noticeable distal longitudinal ridge, and tapered malleoli.[1] The nearly half-meter-long fibula possesses the typical anatomical characters of ceratosaurs.[1]

Classification and systematics

[edit]Arcovenator is a theropod genus nested within the clade Abelisauridae,[1] which in Linnaean taxonomy has the rank of family.[4] This taxonomical group has as close relatives noasaurids within the Abelisauroidea.[1][5] The latter in turn along with Limusaurus and Ceratosaurus nests within Ceratosauria.[1][6]

Distinguishing characters of abelisaurids are their short, tall skulls with extensively sculptured external surfaces, the drastically reduced fore limbs, and the stout hind limbs.[7]

Thierry Tortosa and colleagues conducted a phylogenetic analysis, which is summarized in the cladogram below and is based, in part, on previously published works including both the newly discovered fossil remains and other described but unnamed French abelisaurs.[1]

| Majungasaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||

The study generally agrees with previous results, namely a relatively recent one obtained both by Matthew Carrano and Scott Sampson (2008)[8] and Diego Pol and Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2012)[6] of a clade that includes at least Majungasaurus, Indosaurus and Rajasaurus, which in the more recent analysis includes Arcovenator.[1] Tortosa et al.. name this well-supported clade the Majungasaurinae, ranking it as subfamily and defining it to contain all abelisaurids more closely related to Majungasaurus than to Carnotaurus.[1] The members of this taxonomical group have various cranial characters in common including an elongated antorbital fenestra, and a parietal with a sagittal crest that widens anteriorly into a triangular surface.[1] Also of note is that, in partial agreement with some analyses, the more fragmentary French ceratosaur remains are placed within Abelisauridae, and contrary to others, Abelisaurus is recovered as a carnotaurin.[1]

Also, insights into the paleobiogeography of abelisauroids exist; just presence of them in the so-called European Archipelago[9] confounds hypotheses that only consider the continents derived from the breakup of Mesozoic Gondwana.[1] Two lineages of European abelisaurs are discerned: a basal one, including the small Albian Genusaurus and Lower Campanian Tarascosaurus, and a derived one, the larger Campanian Arcovenator allied with the Madagascan Majungasaurus and the Indian Rajasaurus in Majungasaurinae.[1] As the inferred character distributions obtained through the phylogenetic analysis make it unlikely that these lineages are more closely related to each other than to other abelisaurids, this suggests a more complicated series of events regarding their biogeography with vicariance applicable to the older one and oceanic dispersal being likelier for the more recent one.[1] These results lend support to the proposed role of Africa as a hub for faunal movements between Europe and India or Madagascar[10] and the isolation of South American abelisaurids.[1][8]

Discovery and naming

[edit]The fossil remains of A. escotae were found near Pourrières, Var department, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, during preventive paleontological and archaeological prospection activities before construction took place on the stretch of the A8 motorway between Châteauneuf-le-Rouge and Saint Maximin.[1][11][12] The pertinent late Campanian strata (between 72 and 76 million years ago)[13][14][15] of the Lower Argiles Rutilantes Formation are located in the Aix-en-Provence Basin of southeastern France.[1] The holotype of Arcovenator escotae, housed at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle d’Aix-en-Provence, was found closely associated in a single stratum of fluvial sandstone and is made up of specimens MHNA-PV-2011.12.1, a braincase in articulation with a right postorbital, MHNA-PV-2011.12.2, a left squamosal, MHNA.PV.2011.12.15, a tooth, MHNA.PV.2011.12.5, MHNA.PV.2011.12.5, an anterior caudal vertebra, MHNA.PV.2011.12.3, a right tibia, and MHNA.PV.2011.12.4, a right fibula.[1] Two anterior caudal vertebrae (MHNA.PV.2011.12.198 and MHNA.PV.2011.12.213) and three teeth (MHNA.PV.2011.12.20, MHNA.PV.2011.12.187 and MHNA.PV.2011.12.297) found close both in distance and depth were also referred to the species, but belonging to different individuals.[1] It is likely that a maxilla, the sole fossil found of the so-called Pourcieux abelisaurid, is referable to at least this genus on account of both its close proximity in time and space and the results of the phylogenetic analysis.[1][8] Numerous abelisaurid teeth from the early Maastrichtian strata from Laño are referred to as Arcovenator sp.[2]

The genus name Arcovenator derives from the river Arc as the locality is set within its basin and the Latin word for hunter, venator.[1] The specific epithet 'escotae' honors Escota, a motorway concession company,[16] which since 2006 has provided the necessary funds to excavate the locality.[1]

Paleoecology

[edit]A. escotae lived on the Ibero-Armorican island,[1] a relatively large landmass formed by what are now parts of France, Spain, and Portugal.[9] The compressional subsidence basin of Aix-en-Provence was a low-relief endorheic affair located at a paleolatitude of 35°N, and had its borders to north and south in the form of limestone highlands, respectively the Sainte Victoire and Etoile massifs, and to the east as the Maure Mountains.[13] The sediment from these sources flowed along rivers into a perennial lake originating interbedded lacustrine, alluvial and fluvial sediments at the time of Arcovenator, when the climate was warm, subhumid with marked seasons.[13] The fossil remains were found in one of the formation's various levels of fluvial sandstone,[1] characteristic of a river's mouth or when it overflows its banks,[13] along with hybodonts, the turtles Foxemys and Solemys, the crocodylomorphs Musturzabalsuchus and Ischyrochampsa, azhdarchid pterosaurs, titanosaurian sauropods, the ornithopod Rhabdodon and nodosaurids.[1] The abundance of fragmentary remains of medium-sized abelisaurs, especially teeth in this and other localities of the region show that these animals would have been relatively common in the landscape.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Tortosa, Thierry; Eric Buffetaut; Nicolas Vialle; Yves Dutour; Eric Turini; Gilles Cheylan (2014). "A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of southern France: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Annales de Paléontologie. 100 (1): 63–86. Bibcode:2014AnPal.100...63T. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2013.10.003.

- ^ a b Isasmendi, Erik; Torices, Angelica; Canudo, José Ignacio; Currie, Philip J.; Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier (2022). "Upper Cretaceous European theropod palaeobiodiversity, palaeobiogeography and the intra-Maastrichtian faunal turnover: new contributions from the Iberian fossil site of Laño". Papers in Palaeontology. 8 (1). Bibcode:2022PPal....8E1419I. doi:10.1002/spp2.1419. hdl:10810/56781. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 246028305.

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. Bibcode:2017CrRes..69...71G. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Krause, David W.; Sampson, Scott D.; Carrano, Matthew T.; O'Connor, Patrick M. (2007). "Overview of the history of discovery, taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". In Sampson, Scott D.; Krause, David W. (eds.). Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 8. Vol. 27. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[1:OOTHOD]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 13274054.

- ^ Sereno, Paul C.; Wilson, JA; Conrad, JL (2007). "New dinosaurs link southern landmasses in the Mid-Cretaceous". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 271 (1546): 1325–1330. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2692. PMC 1691741. PMID 15306329.

- ^ a b Diego Pol & Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2012). "A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1804): 3170–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660. PMC 3385738. PMID 22628475.

- ^ Tykoski, Ronald B.; Rowe, Timothy (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 47–70. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b c Carrano, M.T.; S.D. Sampson (2008). "The phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria:Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 183–236. Bibcode:2008JSPal...6..183C. doi:10.1017/s1477201907002246. S2CID 30068953.

- ^ a b Dalla Vecchia, Fabio M. (2006). "Telmatosaurus and the Other Hadrosaurids of the Cretaceous European Archipelago. An Overview" (PDF). Natura Nascosta (32): 1–55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-29. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ^ Ezcurra, M.D.; F.L. Agnolín (2012). "An abelisauroid dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Laurasia and its implications on theropod palaeobiogeography and evolution". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 123 (3): 500–507. Bibcode:2012PrGA..123..500E. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2011.12.003.

- ^ "VINCI Autoroutes | Quand l'autoroute mène aux dinosaures…" (in French). VINCI Autoroutes. 4 June 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "VINCI Autoroutes | L'autoroute du temps sur l'A8" (in French). VINCI Autoroutes. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Cojan, Isabelle; Marie-Gabrielle Moreau (2006). "Correlation of Terrestrial Climatic Fluctuations With Global Signals During the Upper Cretaceous–Danian in a Compressive Setting (Provence, France)" (PDF). Journal of Sedimentary Research. 76 (3): 589–604. Bibcode:2006JSedR..76..589C. doi:10.2110/jsr.2006.045.

- ^ Ogg, J.G.; L.A. Hinnov (2012). "27: Cretaceous". In Felix M. Gradstein; James G. Ogg; Mark D. Schmitz; Gabi M. Ogg (eds.). The Geologic Time Scale 2012. p. 810. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-59425-9.00027-5. ISBN 9780444594259.

- ^ Thibault, Nicolas; Dorothée Husson; Rikke Harlou; Silvia Gardin; Bruno Galbrun; Emilia Huret; Fabrice Minoletti (15 June 2012). "Astronomical calibration of upper Campanian–Maastrichtian carbon isotope events and calcareous plankton biostratigraphy in the Indian Ocean (ODP Hole 762C): Implication for the age of the Campanian–Maastrichtian boundary". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 337–338 (52–71): 52–71. Bibcode:2012PPP...337...52T. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.027.

- ^ "VINCI Autoroutes | Escota". VINCI Autoroutes. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2013.