Arrowslit

An arrowslit (often also referred to as an arrow loop, loophole or loop hole, and sometimes a balistraria) is a narrow vertical aperture in a fortification through which an archer can launch arrows.

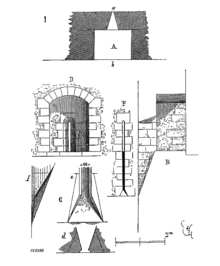

The interior walls behind an arrow loop are often cut away at an oblique angle so that the archer has a wide field of view and field of fire. Arrow slits come in a remarkable variety. A common and recognizable form is the cross. The thin vertical aperture permits the archer large degrees of freedom to vary the elevation and direction of his bowshot but makes it difficult for attackers to harm the archer since there is only a small target at which to aim.

Balistraria can often be found in the curtain walls of medieval battlements beneath the crenellations.

History

The invention of the arrowslit is attributed to Archimedes during the siege of Syracuse in 214–212 BC (although archaeologic evidence supports their existence in Egyptian Middle Kingdom forts around 1860 BC).[1] Slits "of the height of a man and about a palm's width on the outside" allowed defenders to shoot bows and scorpions (an ancient siege engine) from within the city walls.[2] Although used in late Greek and Roman defences, arrowslits were not present in early Norman castles. They are only reintroduced to military architecture towards the end of the 12th century, with the castles of Dover and Framlingham in England, and Richard the Lionheart's Château Gaillard in France. In these early examples, arrowslits were positioned to protect sections of the castle wall, rather than all sides of the castle. In the 13th century, it became common for arrowslits to be placed all around a castle's defences.[2]

Design

In its simplest form, an arrowslit was a thin vertical opening; however, the different weapons used by defenders sometimes dictated the form of arrowslits. For example, openings for longbowmen were usually tall and high to allow the user to shoot standing up and make use of the 6 ft (1.8 m) bow, while those for crossbowmen were usually lower down as it was easier for the user to shoot whilst kneeling to support the weight of the weapon. It was common for arrowslits to widen to a triangle at the bottom, called a fishtail, to allow defenders a clearer view of the base of the wall.[3] Immediately behind the slit there was a recess called an embrasure; this allowed a defender to get close to the slit without being too cramped.[4] The width of the slit dictated the field of fire, but the field of vision could be enhanced by the addition of horizontal openings; they allowed defenders to view the target before it entered range.[3]

Usually, the horizontal slits were level, which created a cross shape, but less common was to have the slits off-set (called displaced traverse slots) as demonstrated in the remains of White Castle in Wales. This has been characterised as an advance in design as it provided attackers with a smaller target;[5] however, it has also been suggested that it was to allow the defenders of White Castle to keep attackers in their sights for longer because of the steep moat surrounding the castle.

When an embrasure linked to more than one arrowslit (in the case of Dover Castle, defenders from three embrasures can shoot through the same arrowslit) it is called a "multiple arrowslit".[6] Some arrowslits, such as those at Corfe Castle, had lockers nearby to store spare arrows and bolts; these were usually located on the right hand side of the slit for ease of access and to allow a rapid rate of fire.[3]

See also

References

- ^ "7.10 Egyptian Forts in Nubia and Indigenous Peoples There". worldhistory.biz. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b Jones & Renn 1982, p. 445.

- ^ a b c Friar 2003, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Friar 2003, p. 104

- ^ Jones & Renn 1982, p. 451

- ^ Friar 2003, p. 182

Bibliography

- Friar, Stephen (2003), The Sutton Companion to Castles, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2

- Jones, Peter; Renn, Derek (1982), "The military effectiveness of Arrow Loops: Some experiments at White Castle", Château Gaillard: Etudes de castellologie médiévale, IX–X, Centre de Recherches Archéologiques Médiévales: 445–456

External links

Media related to Arrowslits at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arrowslits at Wikimedia Commons