Basilica

This article's images may require adjustment of image placement, formatting, and size. (November 2016) |

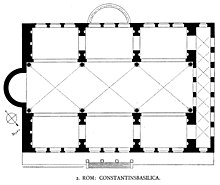

The Latin word basilica (derived from Greek βασιλικὴ στοά, lit. "royal stoa", serving as the tribunal chamber of a king) has three distinct applications in modern English. The word was originally used to describe an ancient Roman public building where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions. To a large extent these were the town halls of ancient Roman life. The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. These buildings, an example of which is the Basilica Ulpia, were rectangular, and often had a central nave and aisles, usually with a slightly raised platform and an apse at each of the two ends, adorned with a statue perhaps of the emperor, while the entrances were from the long sides.[1][2]

By extension the name was applied to Christian churches which adopted the same basic plan and it continues to be used as an architectural term to describe such buildings, which form the majority of church buildings in Western Christianity, though the basilican building plan became less dominant in new buildings from the later 20th century. Later, the term came to refer specifically to a large and important Roman Catholic church that has been given special ceremonial rights by the Pope.

Roman Catholic basilicas are Catholic pilgrimage sites, receiving tens of millions of visitors per year.[3][4] In December 2009 the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City set a new record with 6.1 million pilgrims during Friday and Saturday for the anniversary of Our Lady of Guadalupe.[5]

Architecture

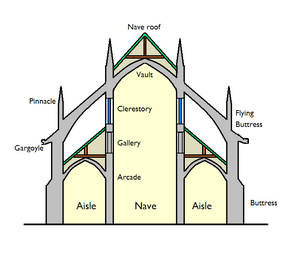

The Roman basilica was a large public building where business or legal matters could be transacted. The first basilicas had no religious function at all. As early as the time of Augustus, a public basilica for transacting business had been part of any settlement that considered itself a city, used in the same way as the late medieval covered market houses of northern Europe, where the meeting room, for lack of urban space, was set above the arcades, however. Although their form was variable, basilicas often contained interior colonnades that divided the space, giving aisles or arcaded spaces on one or both sides, with an apse at one end (or less often at each end), where the magistrates sat, often on a slightly raised dais. The central aisle tended to be wide and was higher than the flanking aisles, so that light could penetrate through the clerestory windows.

The oldest known basilica, the Basilica Porcia, was built in Rome in 184 BC by Cato the Elder during the time he was Censor. Other early examples include the basilica at Pompeii (late 2nd century BC).

Probably the most splendid Roman basilica (see below) is the one begun for traditional purposes during the reign of the pagan emperor Maxentius and finished by Constantine I after 313 AD.

Basilicas in the Roman Forum

- Basilica Porcia: first basilica built in Rome (184 BC), erected on the personal initiative and financing of the censor Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder) as an official building for the tribunes of the plebs

- Aemilian Basilica, built by the censor Aemilius Lepidus in 179 BC

- Basilica Sempronia, built by the censor Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 169 BC

- Basilica Opimia, erected probably by the consul Lucius Opimius in 121 BC, at the same time that he restored the temple of Concord (Platner, Ashby 1929)

- Julian Basilica, initially dedicated in 46 BC by Julius Caesar and completed by Augustus 27 BC to 14 AD

- Basilica Argentaria, erected under Trajan, emperor from 98 AD to 117AD

- Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (built between 308 and 312 AD)

Palace basilicas

In the Roman Imperial period (after about 27 BCE), a basilica for large audiences also became a feature in palaces. In the 3rd century AD, the governing elite appeared less frequently in the forums.

They now tended to dominate their cities from opulent palaces and country villas, set a little apart from traditional centers of public life. Rather than retreats from public life, however, these residences were the forum made private.(Peter Brown, in Paul Veyne, 1987)

Seated in the tribune of his basilica, the great man would meet his dependent clientes early every morning.

A private basilica excavated at Bulla Regia (Tunisia), in the "House of the Hunt", dates from the first half of the 5th century. Its reception or audience hall is a long rectangular nave-like space, flanked by dependent rooms that mostly also open into one another, ending in a semi-circular apse, with matching transept spaces. Clustered columns emphasised the "crossing" of the two axes.

Christian adoption of the basilica form

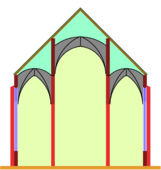

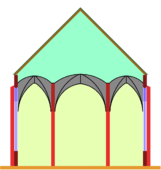

Variations: Where the roofs have a low slope, the gallery may have own windows or may be missing

The remains of a large subterranean Neopythagorean basilica dating from the 1st century AD were found near the Porta Maggiore in Rome in 1915. The ground-plan of Christian basilicas in the 4th century was similar to that of this Neopythagorean basilica, which had three naves and an apse.

In the 4th century, once the Imperial authorities had decriminalised Christianity with the 313 Edict of Milan, and with the activities of Constantine the Great and his mother Helena, Christians were prepared to build larger and more handsome edifices for worship than the furtive meeting-places (such as the Cenacle, cave-churches, house churches such as that of the Roman consuls John and Paul) they had been using. Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable, for their pagan associations, and because pagan cult ceremonies and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, as a backdrop. The usable model at hand, when Constantine wanted to memorialise his imperial piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilicas.[6]

There were several variations of the basic plan of the secular basilica, always some kind of rectangular hall, but the one usually followed for churches had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end opposite to the main door at the other end. In, and often also in front of, the apse was a raised platform, where the altar was placed, and from where the clergy officiated. In secular building this plan was more typically used for the smaller audience halls of the emperors, governors, and the very rich than for the great public basilicas functioning as law courts and other public purposes.[7] Constantine built a basilica of this type in his palace complex at Trier, later very easily adopted for use as a church. It is a long rectangle two storeys high, with ranks of arch-headed windows one above the other, without aisles (there was no mercantile exchange in this imperial basilica) and, at the far end beyond a huge arch, the apse in which Constantine held state.

Comparison of profiles of churches

-

Basilical structure: The central nave extends to one or two storeys more than the lateral aisles, and it has upper windows.

-

Pseudobasilica (i. e. false basilica): The central nave extends to an additional storey, but it has no upper windows.

-

Stepped hall: The vaults of the central nave begin a bit higher than those of the lateral aisles, but there is no additional storey.

-

Hall church: All vaults are almost on the same level.

Development

Putting an altar instead of the throne, as was done at Trier, made a church. Basilicas of this type were built in western Europe, Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine, that is, at any early centre of Christianity. Good early examples of the architectural basilica include the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem (6th century AD), the church of St Elias at Thessalonica (5th century AD), and the two great basilicas at Ravenna.

The first basilicas with transepts were built under the orders of Emperor Constantine, both in Rome and in his "New Rome", Constantinople:

- "Around 380, Gregory Nazianzen, describing the Constantinian Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople, was the first to point out its resemblance to a cross. Because the cult of the cross was spreading at about the same time, this comparison met with stunning success." (Yvon Thébert, in Veyne, 1987)

Thus, a Christian symbolic theme was applied quite naturally to a form borrowed from civil semi-public precedents. The first great Imperially sponsored Christian basilica is that of St John Lateran, which was given to the Bishop of Rome by Constantine right before or around the Edict of Milan in 313 and was consecrated in the year 324. In the later 4th-century, other Christian basilicas were built in Rome: Santa Sabina, and St Paul's Outside the Walls (4th century), and later St Clement (6th century).

A Christian basilica of the 4th or 5th century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street. This was the architectural ground-plan of St Peter's Basilica in Rome, until in the 15th century it was demolished to make way for a modern church built to a new plan.

In most basilicas, the central nave is taller than the aisles, forming a row of windows called a clerestory. Some basilicas in the Caucasus, particularly those of Georgia and Armenia, have a central nave only slightly higher than the two aisles and a single pitched roof covering all three. The result is a much darker interior. This plan is known as the "oriental basilica", or "pseudobasilica" in central Europe.

Gradually, in the early Middle Ages there emerged the massive Romanesque churches, which still kept the fundamental plan of the basilica.

In the United States the style was copied with variances. A rare American church built imitating the architecture of an Early Christian basilica, St. Mary's (German) Church in Pennsylvania, was demolished in 1997.

-

...is a pseudobasilica

Basilicas in Eastern Orthodoxy

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, in general, the basilica is a mere architectural description of churches built in the ancient style. It bears no significance with regard to precedence or importance of the particular building or clerics associated with it. Eastern basilicas may be single-naved, or have the nave flanked by one or two pairs of lower aisles; it may have a dome in the middle: in this case it is called a "domed basilica".

In Romania, the word for church both as a building and as an institution is biserică, derived from the term basilica.

The style influenced the construction of early wooden churches.

Ecclesiastical basilicas

The Early Christian purpose-built basilica was the cathedral basilica of the bishop, on the model of the semi-public secular basilicas, and its growth in size and importance signalled the gradual transfer of civic power into episcopal hands, which was under way in the 5th century. Basilicas in this sense are divided into classes, the major ("greater") basilicas and the minor basilicas; there are three other papal and several pontifical minor basilicas in Italy, and over 1,400 lesser basilicas around the world.

Churches designated as papal basilicas, in particular, possess a papal throne and a papal high altar, at which no one may celebrate Mass without the pope's permission.[8]

Numerous basilicas are notable shrines, often even receiving significant pilgrimages, especially among the many that were built above a confessio or the burial place of a martyr – although this term now usually designates a space before the high altar that is sunk lower than the main floor level (as in the case in St Peter's and St John Lateran in Rome) and that offer more immediate access to the burial places below.

Ranking of churches

The papal or major basilicas outrank in precedence all other churches. Other rankings put the cathedral (or co-cathedral) of a bishop ahead of all other churches in the same diocese, even if they have the title of minor basilica. If the cathedral is that of a suffragan diocese, it yields precedence to the cathedral of the metropolitan see. The cathedral of a primate is considered to rank higher than that of other metropolitan(s) in his circonscription (usually a present or historical state). Other classifications of churches include collegiate churches, which may or may not also be minor basilicas.

Major or papal basilicas

To this class belong only the four great papal churches of Rome, which among other distinctions have a special "holy door" and to which a visit is always prescribed as one of the conditions for gaining the Roman Jubilee. Upon relinquishing in 2006 the title of Patriarch of the West, Pope Benedict XVI renamed these basilicas from "Patriarchal Basilicas" to "Papal Basilicas".

- St. John Lateran, also called the Lateran Basilica, is the cathedral of the Bishop of Rome, the Pope.

- St. Peter's, also called the Vatican Basilica, is a major pilgrimage site, built over the burial place of Saint Peter.

- St. Paul Outside the Walls, also known as the Ostian Basilica because it is situated on the road that led to Ostia, is built over the burial place of Paul the Apostle.

- St. Mary Major, also called the Liberian Basilica because the original building (not the present one) was attributed to Pope Liberius, is the largest church in Rome dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The four papal or major basilicas were formerly known as "patriarchal basilicas". Together with the minor basilica of St Lawrence outside the Walls, they were associated with the five ancient patriarchal sees of Christendom (see Pentarchy): St John Lateran was associated with Rome, St Peter's with Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), St Paul's with Alexandria (in Egypt), St Mary Major with Antioch (the Levant) and St Lawrence with Jerusalem.

Minor basilicas

The privileges attached to the status of minor basilica, which is conferred by papal brief, include a certain precedence before other churches, the right of the conopaeum (a baldachin resembling an umbrella; also called umbraculum, ombrellino, papilio, sinicchio, etc.) and the bell (tintinnabulum), which are carried side by side in procession at the head of the clergy on state occasions, and the cappa magna which is worn by the canons or secular members of the collegiate chapter when assisting at the Divine Office.[8] In the case of major basilicas these umbraculae are made of cloth of gold and red velvet, while those of minor basilicas are made of yellow and red silk—the colours traditionally associated with both the Papal See and the city of Rome.

There are five "pontifical" minor basilicas in the world (the word "pontifical" referring to the title "pontiff" of a bishop, and more particularly of the Bishop of Rome): Pontifical Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary of Pompeii, the Pontifical Basilica of Saint Nicholas in Bari, the Pontifical Basilica of Saint Anthony in Padua, the Pontifical Basilica of the Holy House at Loreto, the Pontifical Basilica of St Michael in Madrid, Spain.

Until Pope Benedict XVI, the title "patriarchal" (now "papal") was officially given to two minor basilicas[9] associated with Saint Francis of Assisi situated in or near his home town:

The description "patriarchal" still applies to two minor basilicas[9] associated with archbishops who have the title of patriarch: the Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of St Mark in Venice and the Patriarchal Basilica of Aquileia.

Not all Patriarchal cathedrals are minor basilicas, notably: the Patriarchal Cathedral of St Mary Major in Lisbon, Portugal, the Patriarchal Cathedral of Santa Catarina, Old Goa, India.

Basilicas and pilgrimages

In recent times, the title of minor basilica has been attributed to important pilgrimage churches. In 1999 Bishop Francesco Giogia stated that the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City (constructed in the 20th century) was the most visited Catholic shrine in the world, followed by San Giovanni Rotondo and Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida in Brazil.[4] Millions of pilgrims visit the shrines of Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima. Pilgrimage basilicas continue to attract well over 30 million pilgrims per year.[4]

Every year, on 13 May and 13 October, the significant dates of the Fatima apparitions, pilgrims fill the country road that leads to the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Fátima with crowds that approach one million on each day.[10] In December 2009 the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe set a new record with 6.1 million pilgrims during Friday and Saturday for the anniversary of Our Lady of Guadalupe.[5]

Ecclesiastical basilicas by region

In 2010, 1587 churches bore the title of basilica.[11]

| Region | Basilicas |

|---|---|

| Europe | 1187 |

| Americas | 327 |

| Asia | 49 |

| Oceania | 6 |

| Africa | 18 |

| Total | 1587 |

See also

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

- Cathedral

- Duomo

- List of basilicas

- Roman architecture

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

References and sources

- References

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture (2013 ISBN 978-0-19968027-6), p. 117

- ^ Helen Dietz, "The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture"

- ^ a b Sacred Travels by Lester Meera 2011 ISBN 1-4405-2489-0 page 53

- ^ a b c "Eternal Word Television Network, Global Catholic Network". Ewtn.com. 13 June 1999. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Zenith News December 14, 2009". Zenit.org. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Basilica Plan Churches". Cartage.org.lb. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Syndicus, 40

- ^ a b Gietmann, G.; Thurston, Herbert (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b The title of minor basilicas was first attributed to the church of San Nicola di Tolentino in 1783. Older minor basilicas are referred to as "immemorial basilica".

- ^ Trudy Ring, 1996, International Dictionary of Historic Places, ISBN 978-1-884964-02-2 page 245

- ^ Gcatholic (2010). "Basilicas in the World". Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Sources

- Krautheimer, Richard (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine architecture. New Haven: The Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05294-4Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Architecture of the basilica, well illustrated.

- Syndicus, Eduard, Early Christian Art, Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- Basilica Porcia

- W. Thayer, "Basilicas of Ancient Rome": from Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby), 1929. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Oxford University Press)

- Paul Veyne, ed. A History of Private Life I: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, 1987

- Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Gietmann, G.; Thurston, Herbert (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- List of All Major, Patriarchal and Minor Basilicas & statistics by Giga-Catholic Information