Battle of San Juan and Chorrillos

| Battle of San Juan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the Pacific | |||||||

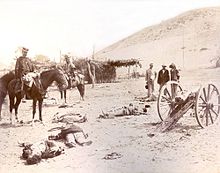

Troop movements at Chorrillos | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Manuel Baquedano | Nicolás de Piérola | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

23,129 men 88 guns |

22,000 men 85+ guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,107 killed & wounded[2] |

8,500 killed 2,500 wounded 4,000 captured 87 cannons captured 19 machine guns captured 4 flags captured Total: 15,000 casualties[3] | ||||||

The Battle of San Juan, also known as the Battle of San Juan and Chorrillos, was the first of two battles in the Lima Campaign during the War of the Pacific, and was fought on 13 January 1881. This battle is really a group of smaller, yet fierce confrontations at the defensive strongholds of Villa, Chorrillos, Santiago de Surco, San Juan de Miraflores, Santa Teresa and Morro Solar. The Chilean army led by Gen. Manuel Baquedano inflicted a harsh defeat on the Peruvian army commanded by the Supreme Chief Nicolás de Piérola. The Chilean triumph eliminated the first defensive line guarding Lima, and almost obliterated the Peruvian army defending it.

At the end of the battle, the town of Chorrillos was burnt to the ground by the Chilean army trying to eradicate the Peruvian defenders garrisoned there. During the night, civilian abuses were committed by drunk soldiers.

Despite this result, another battle had to be fought in order that the Chilean army could enter the Peruvian capital city at Miraflores, two days later.

Prologue

[edit]After the Chilean victories at the battles of Tacna and Arica, the southern department of Peru was in Chilean hands, so the Chilean government had no desire to continue the war. After all, the Bolivian zone in dispute which started the conflict was under Chilean domain, as well as the southernmost Peruvian department of Tarapaca, which was not in dispute but had started to play a significant role in financing the Chilean war effort. Despite this, the public opinion was divided. One side desired to end the war by conquering Lima, and the other one wanted to end the conflict right then, avoiding more casualties. The public debate reached the Chilean Congress, were José Miguel Balmaceda declared: The peace is at Lima, and nowhere else.[4] This political and social climate forced both the Chilean government and its high command to plan a new campaign with the objective to obtain an unconditional capitulation at the Peruvian capital city. Hence, the peace talks on the Lackawanna known as the Conference of Arica were futile.

Meanwhile, Nicolas de Pierola, at that time the dictator of Peru, did what he could to gather an army of conscripts at Lima and its surroundings (an "army" made basically of hastily trained and ill-equipped civilians, teenagers and senior citizens) but the defense was organized only when the Chilean army occupied Pisco. Since it became obvious the attack would come from the south, a long line of defenses was set at Chorrillos and Miraflores, under the advisement of the engineers Gorbitz and Arancibia. The line of Chorrillos was 15 kilometres long, lying from Marcavilca hill to La Chira, passing through the acclivities of San Juan and Santa Teresa.

Preliminary situation

[edit]The Chilean situation

[edit]

During the second half of December 1880, the Chilean Navy transported a number of divisions from Pisco and Paracas to Curayacu. Only Patricio Lynch's brigade took a land route. By 21 December, the invasion convoy was at Chilca. A detachment of ninety horsemen of the Cazadores a Caballo Cavalry Regiment, led by Lt. Col. Ambrosio Letelier scouted the terrain until they reached Lurin, finding no presence of Peruvian troops. Another 25 Cazadores joined with Lynch at Bujama.

Meanwhile, a massive Chilean disembarkment at Curayaco took place on 22 December. The following day, Col. Gana's brigade marched over the Lurin valley, where some cavalry engaged in a skirmish with Peruvian soldiers, but by 07:00, the Chilean forces reached their objective, and by 11:00 entered in the town of San Pedro de Lurin.

On 24 December, a small vanguard force formed by four infantry companies and 200 Cazadores marched to Manchay, from where it went to Pachacamac, in order to protect the bridge there. Here, this force engaged Peruvian troops in a fierce skirmish. On 25 December, the 1st Brigade of Sotomayor's II Division was sent to Pachacamac.

With the arrival of Lynch's brigade, the entire Chilean army gathered about 29,935 soldiers, organized into four divisions by the War Minister José Fco. Vergara.[5]

Two companies of the Curico Infantry Regiment with 300 artillery men were left here taking care of the wounded generated by the march of part of the Chilean troops.[5] On the afternoon of 12 January 23,129 men advanced to Chorrillos, reaching their destination that night.

The Peruvian situation

[edit]Meanwhile, as the Chilean army landed on Curayaco and moved to Lurin, the Peruvian government mobilized all men between 18 and 50 years, leaving those older than 50 years in a stationary reserve, whilst the younger ones formed the Line Army (Spanish: Ejército de Línea).[3] Hence, it was organised into two Southern Armies at Tacna and Arequipa, one Centre Army and one Northern Army. Pierola ordered the farmers of the Lima Department to form a mobile column and beset the Chilean forces landed in any way they could, and to serve as scouts.

The American engineer Paul Boyton, who was hired by the Peruvian government to develop torpedoes to be used against the Chilean navy, narrates that "the Peruvian troops were of natives who had been recruited in the mountain ranges and forced to fight, hundreds of them never had seen before a city".

When these contingents arrived at Lima, they numbered around 18,000 men. 10,000 soldiers were sent to the first defensive line set at Chorrillos and the rest were put as a reserve at the second line of Miraflores.

The Peruvian forces defending the line at Chorrillos were under the command of the Supreme Chief Nicolás de Piérola. The line stretched from the town of Chorrillos by the sea to Pamplona hill, extending about 15 km long. This army deployed with Miguel Iglesias' I Army Corps guarding the right flank of the Peruvian line, followed by Caceres' IV Army Corps. Next to it was Davila's III Army Corps and the II Army Corps of Belisario Suarez was placed in the rear as a reserve.[3]

The artillery deployed four Grieve-system cannons at Marcavilca hill and La Chira, and four Vavasseur cannons at Chorrillos; at Villa, another battery of four Grieves cannons and at Santa Teresa were fifteen Whites, four Grieves, four Walgely steel pieces, one Armstrong and one Vavasseur. By the left were twelve Grieve cannons, four Whites and two small Selay-system cannons. On the right of San Juan position were eight Whites cannons and fourteen Grieve cannons. At Pamplona were another four Grieve cannons and four Vavasseur cannons.

The attacking plan and defensive layout

[edit]The Chilean high command had two approaches about how to handle this battle. The first one, proposed by Col. Jose Fco. Gana and supported by the War Minister in Campaign Jose Fco. Vergara was a flanking maneuver on the far left of the Peruvian defenses. On the other hand, the plan of General Baquedano was quite similar to the one used in Tacna. It consisted in pressing the attack simultaneously along the entire front line, keeping the Allies from sending reinforcements from one point to another, and exploiting the fact than this defensive line was extensive but thin. At last, Baquedano's plan prevailed, nevertheless a previous skirmish at Ate confirmed that Vergara's plan was possible.[5]

The Peruvian strategy relied on the difficulty of assaulting hilltop positions. Their emplacements were strengthened by a system of trenches for shooters on the hill slopes and hidden devices such as land mines and booby traps, which were poorly installed and did not really work.[3]

The battle

[edit]The Peruvian right flank

[edit]Marcavilca

[edit]At 04:00 on 13 January, the battle began when the sunrise showed the advancing Chilean forces. Lynch's division engaged the troops defending the right flank of the defensive line.[5]

The Nº 9 "Callao" Battalion on the Villa sector was pushed back to Col. Iglesias' I Army Corps, which was also forced to retreat to new positions at Marcavilca. The Peruvian IV Army Corps attacked the I Division, thus Gen. Baquedano ordered the reserve to back Lynch up. This manoeuvre isolated Iglesias from the rest of the Peruvian army, breaking the defensive line as the I Army Corps withdrew from Marcavilca and regrouped at Morro Solar.[6]

The Peruvian centre

[edit]San Juan and Santa Teresa

[edit]

Whilst Lynch was fighting at Marcavilca, Sotomayor's division reached the battlefront and pressed the attack over Canevaro's 3rd Center Division, pinning it down in its position between San Juan and Pamplona. When Gen. Silva sent the Huanuco Battalion as reinforcement, it was rejected and disbanded. This also occurred with the following reinforcements sent to the sector.

Col. Gana's brigade marched onto and hammered the Peruvian positions at Papa and Viva el Peru hills. The "Buin" 1st Line Regiment bayoneted off its defenders,[7] as the "Esmeralda" 7th Line Regiment captured the banner of the Nº 81 "Manco Capac" Battalion. Barbosa's brigade attacked the Peruvian trenches from the south, forcing Davila's Army Corps to retreat from San Juan.

From this point, Gana turned left and charged Caceres' Army Corps left flank, which refolded, splitting the Peruvian line. Cannevaro's division, which was holding up the attack, had no choice but to retreat as well. Hence, the defensive line was now fractured in two points and the battle was turning in Chile's favour. Baquedano sent the Cazadores a Caballo and the Granaderos a Caballo cavalry regiments, led by Manuel Bulnes and Tomas Yavar, trying to stop the Peruvian retreat. The latter died of a gunshot, and Bulnes was injured by a land mine. Despite this, both regiments reached to Pampa de Tebes, but here were stopped by a Peruvian cavalry brigade sent by Silva and an intense infantry fire of the retiring battalions.[8] The rest of Suarez’ battalions retired to Chorrillos suffering heavy casualties in the march. Meanwhile, some dispersed troops were gathered and sent to the second defensive line at Miraflores.

Conclusion

[edit]

Morro Solar

[edit]With the Peruvian line broken now at its center and beginning to collapse, Lagos’ III Division were sent from the Chilean right wing to support Lynch's forces which were sustaining heavy damage. On a controversial decision, Gen. Baquedano ordered the exhausted I Division to make a frontal charge in order to eliminate this Peruvian stronghold. Part of Amunategui's 2nd Brigade, supported by some artillery marched towards Marcavilca. The "Martir Olaya" battery of Col. Arnaldo Panizo poured over the Chileans, inflicting severe casualties. The Chacabuco and the 4th Line regiments took several losses on their attempt at Morro Solar.[9] When the ammunition began to run out, the Chilean brigade retreated attacked by Iglesias near La Calavera hill, but was strengthened by the Atacama Regiment and resumed the attack. When the brigade of Col. Barcelo arrived, Iglesias refolded to Marcavilca.[10]

Lynch divided his division to conquer Marcavilca hill, with one column attacking the flank and the other engaged the front. Jose Maria Soto's column drove the Peruvians out of their positions, but its commander fell in the attempt, being replaced by Marcial Pinto Aguero as the commandant of the Coquimbo Battalion. In a new retreat, to Chorrillos this time, Iglesias was captured.[11]

Chorrillos

[edit]

Suarez' Corps reached Chorrillos and attacked the incoming Chilean forces. Sotomayor's division, along with Urriola's brigade attacked the town; meanwhile Barcelo marched to Morro Solar in order to take Panizo's position. The Peruvians garrisoned in the town, so the Chileans had to fight in every house in order to take it. To make this objective easier, the Chileans set Chorrillos on fire. Being surrounded, Suarez withdrew to Barranco, part of the Miraflores defensive line.

Prior to the occupation of Lima there were fires and sackings by demoralized Peruvian soldiers in the towns of Chorrillos and Barranco; as quoted by Charles de Varigny rendía incondicionalmente. La soldadesca (peruana) desmoralizada y no desarmada saqueaba la ciudad en la noche del 16, el incendio la alumbraba siniestramente y el espanto reinaba en toda ella.

The Chinese residents who betrayed their adoptive country and joined forces with Chilean army also fought alongside the Chileans in the battles of San Juan-Chorrillos and Miraflores, and there was also rioting and looting by non-Chinese workers in the coastal cities. As Heraclio Bonilla has observed; Peruvian oligarchs soon came to fear the popular clashes more than the Chileans, and this was an important reason why they sued for peace. [Source: "From chattel slaves to wage slaves: dynamics of labour bargaining in the Americas", by Mary Turner.]

During the night, Chilean troops entered the town of Chorrillos, and looted the houses, warehouses and Churches. Then the troops burned the town and committed abuses against the Peruvian civilians and themselves during these riots. Almost 200 Chilean soldiers died as a result of the fighting against their own companions. Many civilians were murdered, women were raped, houses and properties were sacked and many foreigners, who had stayed there to protect their houses, were murdered and their properties robbed. The members of the Italian fire fighters Brigade, after attempting to put out the fires, were executed by a Chilean firing squad (they are considered heroes in Peru). Colonel Andrés Avelino Cáceres requested permission to attack the drunken soldiers in the night and save the remains of the population since, as he claimed, most of Chilean troops had scattered and were mutinied and not obeying their officers. Cáceres' plea was not listened by Peruvian President Pierola.

Aftermath

[edit]Both sides had exorbitant losses. The Chilean army had 3,107 men dead or wounded, equivalent to thirteen percent of its personnel. Lynch's and Sotomayor's divisions were the most damaged units. The Peruvian army lost the Guardia Peruana, Cajamarca, Ayacucho "9 de Diciembre", Tarma, Callao, Libres de Trujillo, Junin, Ica and Libres de Cajamarca battalions at Morro Solar, the Zepita at Chorrillos and the Huanuco, Libertad and Ayacucho battalions at San Juan. Besides, the Paucarpata, Jauja, Ancash, Concepción, Piura, 23 de Diciembre and Unión battalions had abundant losses.[5] All this adds up about 8,000 men,[3] 87 cannons, 19 machine guns and 4 battalion banners were captured by the Chilean Army.

The survivors refolded to strengthen Lima's second defensive line at Miraflores, but the defeat had an impact in the Peruvian morale.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–161.

- ^ Army of Chile. Las Relaciones Nominales. Archived July 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Basadre, Jorge (2000). "La Verdadera Epopeya". Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- ^ La Guerra del Pacífico en imágenes, relatos, testimonios; p. 221

- ^ a b c d e Ojeda, Jorge (2000). "La Guerra del Pacífico". Archived from the original on October 24, 2009.

- ^ La Guerra del Pacífico en imágenes, relatos, testimonios; p. 239

- ^ Lt. Col. Juan Leon Garcia's official report, Commander of the Buin 1st Line Infantry Regiment Archived April 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bulnes, Gonzalo (1956). La Guerra del Pacífico. Santiago: Editorial del Pacífico. v. 2, p. 331-343 [1].

- ^ José Domingo Amunátegui (1885). "Arica" 4º de Línea.

- ^ Panizo, Arnaldo (1881). "Official report of the Battle of Chorrillos". February 9, 1881. Lima. Archived from the original on 2007-10-28.

- ^ Recavarren, Isaac (1881). "Carta de contestación al coronel Suárez sobre la batalla de San Juan y Chorrillos". Documentos relativos al 2º. Ejército del Sur 1880. Legajo Nº5. De la colección Isaac Recavarren. Lima. Archived from the original on 2007-10-28.

References

[edit]- Mellafe, Rafael; Pelayo, Mauricio (2004). La Guerra del Pacífico en imágenes, relatos, testimonios. Centro de Estudios Bicentenario.

External links

[edit] Media related to Battle of Chorrillos at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Chorrillos at Wikimedia Commons- Official Report of the colonel Arnaldo Panizo on the battle of the Morro Solar