Béatrice et Bénédict

| Béatrice et Bénédict | |

|---|---|

| Opéra comique by Hector Berlioz | |

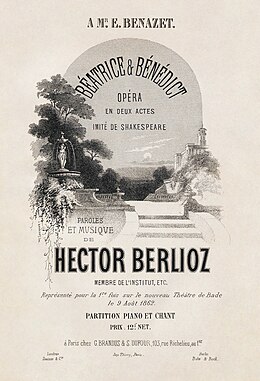

Cover of the first edition vocal score, with illustration by A. Barbizet | |

| Librettist | Hector Berlioz |

| Language | French |

| Based on | Much Ado About Nothing by Shakespeare |

| Premiere | 9 August 1862 |

Béatrice et Bénédict (Beatrice and Benedick) is an opéra comique in two acts by French composer Hector Berlioz.[1] Berlioz wrote the French libretto himself, based in general outline on a subplot in Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing.

Berlioz had been interested in setting Shakespeare's comedy since his return from Italy in 1833, but only composed the score of Béatrice et Bénédict following the completion of Les Troyens in 1858. It was first performed at the opening of the Theater Baden-Baden on 9 August 1862.[2] Berlioz conducted the first two performances of a German version in Weimar in 1863, where, as he wrote in his memoirs, he was "overwhelmed by all sorts of kind attention."

It is the first notable version of Shakespeare's play in operatic form, and was followed by works by, among others, Árpád Doppler, Paul Puget, Charles Villiers Stanford, and Reynaldo Hahn.[3]

Berlioz biographer David Cairns has written: "Listening to the score's exuberant gaiety, only momentarily touched by sadness, one would never guess that its composer was in pain when he wrote it and impatient for death".[4]

Performance history

[edit]Berlioz described the premiere of Béatrice et Bénédict as a "great success" in a letter to his son Louis; he was particularly taken with the performance of Charton-Demeur (who would create the role of Didon in Les Troyens in Paris a year later) and noted that the duo which closes the first half elicited an "astonishing impact".[5]

Although it continued to be staged occasionally in German cities in the years after the premiere, the first performance in France only took place on 5 June 1890 at the Théâtre de l'Odéon, 21 years after its composer’s death, promoted by Élisabeth Greffulhe's Société des Grandes auditions musicales de France, conducted by Charles Lamoureux, and with Juliette Bilbaut-Vauchelet and Émile Engel in the lead roles.[6]

Paul Bastide conducted a notable production of Béatrice et Bénédict in Strasbourg in the late 1940s.[7] It was produced at the Paris Opéra-Comique in 1966 conducted by Pierre Dervaux but with recitatives by Tony Aubin,[8] and in February 2010 under Emmanuel Krivine.[9]

The UK premiere was on 24 March 1936 in Glasgow under Erik Chisholm.[10] The English National Opera opened a production on 25 January 1990, with wife and husband Ann Murray and Philip Langridge in the title roles.[11] The work was first performed in New York in 1977 as a concert performance at Carnegie Hall, Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[12]

Although rather infrequently performed and not part of the standard operatic repertoire, recent productions have included Amsterdam and Welsh National Opera tour in 2001, Prague State Opera (Státní opera Praha) in 2003, Santa Fe Opera in 1998 and 2004, Opéra du Rhin in Strasbourg in 2005, Chicago Opera Theater in 2007, Houston Grand Opera in 2008 (in English), Opera Boston in 2011, Theater an der Wien in 2013, and Glyndebourne in 2016. The first Swedish production of the opera was at Läckö Castle in 2015, and the first in staging in Italy in late 2022 at the Teatro Carlo Felice in Genoa.[13]

Music

[edit]The overture (sometimes played and recorded separately) alludes to several parts of the score without becoming a pot-pourri.[2] The opera opens with a rejoicing chorus and Sicilienne. Héro has a two-part air where she looks expectantly to the return of her love, Claudio.[14] The sparring between Béatrice and Bénédict begins in the next musical number, a duo. An allegretto trio of "conspiratorial humour" for Don Pedro, Claudio and Bénédict,[4] consists of the latter expounding his views on marriage to which the others pass comment. After Somarone has rehearsed his Epithalame grotesque (a choral fugue about love), Bénédict's fast rondo reveals that he has fallen for the plot and will try to be in love. The act ends with a nocturne for Héro and Ursule – a slow duo in 6

8 which W. J. Turner described as "a marvel of indescribable lyrical beauty"[14] and which Grove compares to "Nuit d'ivresse" in Les Troyens.[2]

The second act opens with a drinking song for Somarone and chorus with guitar and tambourine prominent.[2] Next, in an extended air across a wide melodic span, Béatrice acknowledges that she too is powerless against love and in the following trio (added after the premiere) Héro and Ursule join her to extol the joys of marriage. There is a marche nuptiale and the work ends with a brilliant duet marked scherzo-duettino for the title characters whose "sparkle and gaiety" end the comedy perfectly.[14]

Instrumentation

[edit]- Woodwind: 2 flutes, (one with piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 1 cornet à piston, 3 trombones

- Percussion: timpani, tambourine, glasses

- Strings: strings, guitar, 2 harps

Roles

[edit]| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 9 August 1862 Conductor: Hector Berlioz[15] |

|---|---|---|

| Héro, daughter of Léonato | soprano | Monrose |

| Béatrice, niece of Léonato | mezzo | Anne-Arsène Charton-Demeur |

| Bénédict, Sicilian officer, friend of Claudio | tenor | Achille-Félix Montaubry |

| Don Pedro, Sicilian general | bass | Mathieu-Émile Balanqué |

| Claudio, general's aide-de-camp | baritone | Jules Lefort |

| Somarone, a music master | bass | Victor Prilleux |

| Ursule, Héro's lady-in-waiting | contralto | Coralie Geoffroy |

| Léonato, Governor of Messina | spoken | Guerrin |

| A Messenger | spoken | |

| A Notary | spoken | |

| People of Sicily, Lords, Ladies, Musicians, Maids – Chorus | ||

Synopsis

[edit]Act 1

[edit]Don Pedro, prince of Aragon, is visiting Messina after a successful military victory over the Moors, which is celebrated by all of Sicily. He is joined by two friends and fellow soldiers, Claudio and Bénédict. They are greeted by Léonato, governor of Messina, together with his daughter, Héro, and niece, Béatrice.

Héro awaits the return of her fiancé, Claudio, unwounded and rewarded for his valour. Béatrice inquires about and scorns Bénédict. They trade insults, as they have in previous meetings, and tease each other. Bénédict swears to his friends that he will never marry. Later, Claudio and Pedro scheme to trick Bénédict into marrying Béatrice. Knowing that he is listening, Léonato assures Pedro that Béatrice loves Bénédict. Upon hearing this, Bénédict resolves that Béatrice's love must not go unrequited, and so he decides to pursue her. Meanwhile, elsewhere, Héro and her attendant, Ursule, manage to play a similar trick on Béatrice who now believes that Bénédict is secretly in love with her.

Act 2

[edit]To celebrate the pending wedding of Claudio and Héro, Léonato hosts a masquerade party. A local music teacher, Somarone, leads the group in song and everybody enjoys themselves except Béatrice who realizes that she has fallen in love with Bénédict. With Héro and Ursule she sings of the happiness of a bride about to be wed. As she turns to leave she is met by Bénédict, prompting an exchange in which they both attempt to conceal their love for each other. A notary solemnizes the marriage of Claudio and Héro, and, as arranged by Léonato, produces a second contract, asking for another couple to come forward. Bénédict summons the courage to declare his love to Beatrice; the two sign the wedding contract, and the work ends with the words "today a truce is signed, we'll be enemies again tomorrow".

Recordings

[edit]There are several recordings of the opera. The overture, which refers to several passages in the opera without becoming a pot-pourri, is heard on its own in concerts and has been recorded many times.

- Josephine Veasey (Béatrice), John Mitchinson (Bénédict), April Cantelo (Héro), Helen Watts (Ursule), John Cameron (Claudio), John Shirley-Quirk (Don Pedro), Eric Shilling (Somarone), London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Colin Davis. L'Oiseau-lyre SOL 256-7 (1962).

- Janet Baker (Béatrice), Robert Tear (Bénédict), Christiane Eda-Pierre (Héro), Helen Watts (Ursule), Thomas Allen (Claudio), Robert Lloyd (Don Pedro), Jules Bastin (Somarone), London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Colin Davis. Philips 6700 121 (1977)

- Yvonne Minton (Béatrice), Plácido Domingo (Bénédict), Ileana Cotrubaș (Héro), Nadine Denize (Ursule), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Claudio), Roger Soyer (Don Pedro), John Macurdy (Somarone), Orchestre de Paris conducted by Daniel Barenboim. Deutsche Grammophon 2707 130 (1981).

- Susan Graham (Béatrice), Jean-Luc Viala (Bénédict), Sylvia McNair (Héro), Catherine Robbin (Ursule), Gilles Cachemaille (Claudio), Vincent le Texier (Don Pedro), Gabriel Bacquier (Somarone), Lyon Opera Orchestra and Chorus, John Nelson (conductor). Erato 2292-45773 (1991).

- Enkelejda Shkosa (Béatrice), Kenneth Tarver (Bénédict), Susan Gritton (Héro), Sara Mingardo (Ursule), Laurent Naouri (Claudio), Dean Robinson (Don Pedro), David Wilson-Johnson (Somarone), London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Colin Davis. LSO Live (2000)

- Stéphanie d'Oustrac (Béatrice), Paul Appleby (Bénédict), Sophie Karthäuser (Héro), Lionel Lothe (Somarone), Philippe Sly (Claudio), Frédéric Caton (Don Pedro), Katarina Bradìc (Ursule), London Philharmonic Orchestra, The Glyndebourne Chorus, staged by Laurent Pelly, conducted by Antonello Manacorda. 1 DVD Opus Arte 2017

References

[edit]- ^ Berlioz and the Romantic Imagination. Catalogue for exhibition at Victoria and Albert Museum for Berlioz centenary. Art Council, London, 1969, p. 46, exhibit 131 (orchestral manuscript score).

- ^ a b c d Holoman D. K. "Béatrice et Bénédict". In: The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

- ^ Wilson CR. "Shakespeare". In: The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

- ^ a b Cairns, D. Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness 1832–1869. Allen Lane, London, 1999, p. 670.

- ^ MacDonald, Hugh (Ed). Selected Letters of Berlioz (translated by Roger Nichols). Faber & Faber, London, 1995, letter 407.

- ^ Noel E. & Stoullig E. Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 16e édition, 1890. G. Charpentier et Cie, Paris, 1891, pp. 139–145.

- ^ Pitt C. Strasbourg. In: The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London & New York, 1997.

- ^ BnF archives et manuscrits, accessed 2 February 2018.

- ^ Article on Béatrice et Bénédict at the Opéra-Comique in 2010, Artistik Rezo, Marie Torrès, 25 February 2010.

- ^ Erik Chisholm biography. retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ Programme book. Béatrice et Bénédict, English National Opera, 1990.

- ^ "When Shakespeare Hit Berlioz Like a Thunderbolt" by Harold C. Schonberg, The New York Times, 23 October 1977

- ^ Rampone, Giorgio. Report from Genoa. Opera, March 2023, Vol 74 No 3, p291-2.

- ^ a b c Kobbé, Gustav, Harewood, Earl of. Kobbé's Complete Opera Book. Putnam, London and New York, 1954, pp. 730–733.

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Béatrice et Bénédict, 9 August 1862". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

External links

[edit]- Béatrice et Bénédict: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Béatrice et Bénédict libretto, HBerlioz.com