Bertie the Brain

| Bertie the Brain | |

|---|---|

Comedian Danny Kaye photographed having just won against the machine | |

| Designer(s) | Josef Kates |

| Platform(s) | Computer game |

| Release | August 25, 1950 |

| Genre(s) | Tic-tac-toe |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Bertie the Brain was an early computer game, and one of the first games developed in the early history of video games. It was built in Toronto by Josef Kates for the 1950 Canadian National Exhibition. The four meter (13 foot) tall computer allowed exhibition attendees to play a game of tic-tac-toe against an artificial intelligence. The player entered a move on a lit keypad in the form of a three-by-three grid, and the game played out on a grid of lights overhead. The machine had an adjustable difficulty level. After two weeks on display by Rogers Majestic, the machine was disassembled at the end of the exhibition and largely forgotten as a curiosity.

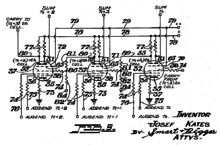

Kates built the game to showcase his additron tube, a miniature version of the vacuum tube, though the transistor overtook it in computer development shortly thereafter. Patent issues prevented the additron tube from being used in computers besides Bertie before it was no longer useful. Bertie the Brain is a candidate for the first video game, as it was potentially the first computer game to have any sort of visual display of the game. It appeared only three years after the 1947 invention of the cathode-ray tube amusement device, the earliest known interactive electronic game to use an electronic display. Bertie's use of light bulbs rather than a screen with real-time visual graphics, however, much less moving graphics, does not meet some definitions of a video game.

History

Bertie the Brain was a computer game of tic-tac-toe, built by Dr. Josef Kates for the 1950 Canadian National Exhibition.[1] Kates had previously worked at Rogers Majestic designing and building radar tubes during World War II, then after the war pursued graduate studies in the computing center at the University of Toronto while continuing to work at Rogers Majestic.[2] While there, he helped build the University of Toronto Electronic Computer (UTEC), one of the first working computers in the world. He also designed his own miniature version of the vacuum tube, called the additron tube, which he registered with the Radio Electronics Television Manufacturers' Association on 20 March 1951 as type 6047.[2][3][4][5]

After filing for a patent for the additron tube, Rogers Majestic pushed Kates to create a device to showcase the tube to potential buyers. Kates designed a specialized computer incorporating the technology and built it with the assistance of engineers from Rogers Majestic.[2][6] The large, four meter (13 foot) tall metal computer could only play tic-tac-toe and was installed in the Engineering Building at the Canadian National Exhibition from 25 August–9 September 1950.[2][7]

The additron-based computer, labeled as "Bertie the Brain" and subtitled "The Electronic Wonder by Rogers Majestic", was a success at the two-week exhibition, with attendees lining up to play it. Kates stayed by the machine when possible, adjusting the difficulty up or down for adults and children. Comedian Danny Kaye was photographed defeating the machine (after several attempts) for Life magazine.[2]

Gameplay

Bertie the Brain was a game of tic-tac-toe in which the player would select the position for their next move from a grid of nine lit buttons on a raised panel. The moves would appear on a grid of nine large squares set vertically on the machine as well as on the buttons, with either an X- or O-shaped light turning on in the corresponding space. The computer would make its move shortly after. A pair of signs to the right of the playfield, alternately lit up with "Electronic Brain" and an X or "Human Brain" and an O, marked which player's turn it was, and would light up along with "Win" when a player had won. Bertie could be set to several difficulty levels.[2] The computer responded almost instantly to the player's moves and at the highest difficulty level was almost unbeatable.[6]

Legacy

After the exhibition, Bertie was dismantled and "largely forgotten" as a novelty. Kates has said that he was working on so many projects at the same time that he had no energy to spare for preserving it, despite its significance.[2] Despite being the first implemented computer game—preceded only by theorized chess programs—and featured in a Life magazine article, the game was largely forgotten, even by video game history books.[6] Bertie's primary purpose, to promote the additron tube, went unfulfilled, as it was the only completed application of the technology. By the time Rogers Majestic pushed Kates to develop a working model for the Exhibition, he had been working on the tubes for a year, developing several revisions, and the University of Toronto team felt that the development was too slow to attempt to integrate them into the UTEC.[8]

Although other firms expressed interest to Kates and Rogers Majestic in using the tubes, issues with acquiring patents prevented him, Rogers Majestic, or the University of Toronto from patenting the tubes anywhere outside Canada until 1955, and the patent application was not accepted in the United States until March 1957, six years after filing.[8][9] By then, research and use of vacuum tubes was heavily waning in the face of the rise of the superior transistor, preventing any re-visitation of Bertie or similar machines.[8] Kates went on to a distinguished career in Canadian engineering, but did not return to working on vacuum tubes or computer games.[6][8]

Bertie was created only three years after the 1947 invention of the cathode-ray tube amusement device, the earliest known interactive electronic game, and while non-visual games had been developed for research computers such as Alan Turing and Dietrich Prinz's chess program for the Ferranti Mark 1 at the University of Manchester, Bertie was the first computer-based game to feature a visual display of any sort.[2][10][11] Bertie is considered under some definitions in contention for the title of the first video game. While definitions vary, the prior cathode-ray tube amusement device was a purely analog electrical game, and while Bertie did not feature an electronic screen it did run on a computer.[12] Another special-purpose computer-based game, Nimrod, was built in 1951, while the software-based tic-tac-toe game OXO and a draughts program by Christopher Strachey were in 1952 the first computer games to display visuals on an electronic screen rather than light bulbs.[6][10][13]

References

- ^ Simmons, Marlene (1975-10-09). "Bertie the Brain programmer heads science council". Ottawa Citizen. p. 17. Retrieved 2014-11-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bateman, Chris (2014-08-13). "Meet Bertie the Brain, the world's first arcade game, built in Toronto". Spacing Magazine. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-11-16.

- ^ "Release #951". RTMA Engineering Department. 1951-03-20.

- ^ Sibley, L. (2007). "Weird Tube of the Month: The 6047". Tube Collector. 9 (5). Tube Collectors Association: 20.

- ^ Osborne, C. S. (2008). "The Additron: A Binary Full Adder in a Tube". Tube Collector. 10 (4). Tube Collectors Association: 12.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Alexander (2014-01-22). "The Priesthood At Play: Computer Games in the 1950s". They Create Worlds. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-18.

- ^ Varley, Frederick (2007). F.H. Varley: Portraits Into the Light. Dundurn Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-55002-675-7.

- ^ a b c d Vardalas, John N. (2001). The Computer Revolution in Canada: Building National Technological Competence. MIT Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-0-262-22064-4.

- ^ US patent 2784312, Kates, Josef, "Electronic Vacuum Tube", issued 1957-03-05

- ^ a b Kowert, Rachel; Quandt, Thorsten (2015-08-27). The Video Game Debate: Unravelling the Physical, Social, and Psychological Effects of Video Games. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-138-83163-6.

- ^ Donovan, Tristan (2010-04-20). Replay: The History of Video Games. Yellow Ant. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-9565072-0-4.

- ^ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012-08-16). Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. XV–7. ISBN 978-0-313-37936-9.

- ^ Hey, Tony; Pápay, Gyuri (2014-11-30). The Computing Universe: A Journey through a Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-521-15018-7.