Block cipher mode of operation

In cryptography, a mode of operation is an algorithm that uses a block cipher to provide an information service such as confidentiality or authenticity.[1] A block cipher by itself is only suitable for the secure cryptographic transformation (encryption or decryption) of one fixed-length group of bits called a block.[2] A mode of operation describes how to repeatedly apply a cipher's single-block operation to securely transform amounts of data larger than a block.[3][4][5]

Most modes require a unique binary sequence, often called an initialization vector (IV), for each encryption operation. The IV has to be non-repeating and, for some modes, random as well. The initialization vector is used to ensure distinct ciphertexts are produced even when the same plaintext is encrypted multiple times independently with the same key.[6] Block ciphers have one or more block size(s), but during transformation the block size is always fixed. Block cipher modes operate on whole blocks and require that the last part of the data be padded to a full block if it is smaller than the current block size.[2] There are, however, modes that do not require padding because they effectively use a block cipher as a stream cipher.

Historically, encryption modes have been studied extensively in regard to their error propagation properties under various scenarios of data modification. Later development regarded integrity protection as an entirely separate cryptographic goal. Some modern modes of operation combine confidentiality and authenticity in an efficient way, and are known as authenticated encryption modes.[7]

History and standardization

The earliest modes of operation, ECB, CBC, OFB, and CFB (see below for all), date back to 1981 and were specified in FIPS 81, DES Modes of Operation. In 2001, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) revised its list of approved modes of operation by including AES as a block cipher and adding CTR mode in SP800-38A, Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation. Finally, in January, 2010, NIST added XTS-AES in SP800-38E, Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: The XTS-AES Mode for Confidentiality on Storage Devices. Other confidentiality modes exist which have not been approved by NIST. For example, CTS is ciphertext stealing mode and available in many popular cryptographic libraries.

The block cipher modes ECB, CBC, OFB, CFB, CTR, and XTS provide confidentiality, but they do not protect against accidental modification or malicious tampering. Modification or tampering can be detected with a separate message authentication code such as CBC-MAC, or a digital signature. The cryptographic community recognized the need for dedicated integrity assurances and NIST responded with HMAC, CMAC, and GMAC. HMAC was approved in 2002 as FIPS 198, The Keyed-Hash Message Authentication Code (HMAC), CMAC was released in 2005 under SP800-38B, Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: The CMAC Mode for Authentication, and GMAC was formalized in 2007 under SP800-38D, Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) and GMAC.

After observing that compositing a confidentiality mode with an authenticity mode could be difficult and error prone, the cryptographic community began to supply modes which combined confidentiality and data integrity into a single cryptographic primitive. The modes are referred to as authenticated encryption, AE or "authenc". Examples of AE modes are CCM (SP800-38C), GCM (SP800-38D), CWC, EAX, IAPM, and OCB.

Modes of operation are nowadays[when?] defined by a number of national and internationally recognized standards bodies. Notable standards organizations include NIST, ISO (with ISO/IEC 10116[5]), the IEC, the IEEE, the national ANSI, and the IETF.

Initialization vector (IV)

An initialization vector (IV) or starting variable (SV)[5] is a block of bits that is used by several modes to randomize the encryption and hence to produce distinct ciphertexts even if the same plaintext is encrypted multiple times, without the need for a slower re-keying process.[6]

An initialization vector has different security requirements than a key, so the IV usually does not need to be secret. However, in most cases, it is important that an initialization vector is never reused under the same key. For CBC and CFB, reusing an IV leaks some information about the first block of plaintext, and about any common prefix shared by the two messages. For OFB and CTR, reusing an IV completely destroys security.[6] This can be seen because both modes effectively create a bitstream that is XORed with the plaintext, and this bitstream is dependent on the password and IV only. Reusing a bitstream destroys security.[8] In CBC mode, the IV must, in addition, be unpredictable at encryption time; in particular, the (previously) common practice of re-using the last ciphertext block of a message as the IV for the next message is insecure (for example, this method was used by SSL 2.0). If an attacker knows the IV (or the previous block of ciphertext) before he specifies the next plaintext, he can check his guess about plaintext of some block that was encrypted with the same key before (this is known as the TLS CBC IV attack).[9]

Padding

A block cipher works on units of a fixed size (known as a block size), but messages come in a variety of lengths. So some modes (namely ECB and CBC) require that the final block be padded before encryption. Several padding schemes exist. The simplest is to add null bytes to the plaintext to bring its length up to a multiple of the block size, but care must be taken that the original length of the plaintext can be recovered; this is trivial, for example, if the plaintext is a C style string which contains no null bytes except at the end. Slightly more complex is the original DES method, which is to add a single one bit, followed by enough zero bits to fill out the block; if the message ends on a block boundary, a whole padding block will be added. Most sophisticated are CBC-specific schemes such as ciphertext stealing or residual block termination, which do not cause any extra ciphertext, at the expense of some additional complexity. Schneier and Ferguson suggest two possibilities, both simple: append a byte with value 128 (hex 80), followed by as many zero bytes as needed to fill the last block, or pad the last block with n bytes all with value n.

CFB, OFB and CTR modes do not require any special measures to handle messages whose lengths are not multiples of the block size, since the modes work by XORing the plaintext with the output of the block cipher. The last partial block of plaintext is XORed with the first few bytes of the last keystream block, producing a final ciphertext block that is the same size as the final partial plaintext block. This characteristic of stream ciphers makes them suitable for applications that require the encrypted ciphertext data to be the same size as the original plaintext data, and for applications that transmit data in streaming form where it is inconvenient to add padding bytes.

Common modes

Many modes of operation have been defined. Some of these are described below.

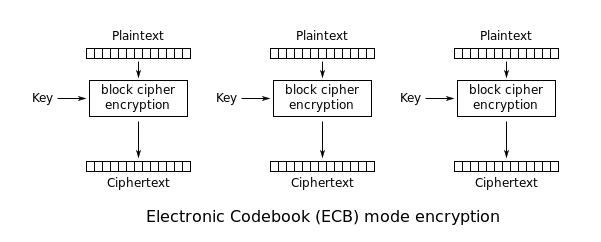

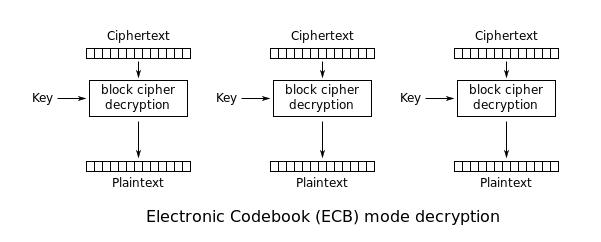

Electronic Codebook (ECB)

| ECB | |

|---|---|

| Electronic Codebook | |

| Encryption parallelizable: | Yes |

| Decryption parallelizable: | Yes |

| Random read access: | Yes |

The simplest of the encryption modes is the Electronic Codebook (ECB) mode. The message is divided into blocks, and each block is encrypted separately.

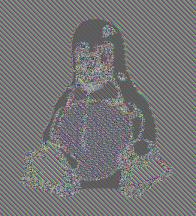

The disadvantage of this method is that identical plaintext blocks are encrypted into identical ciphertext blocks; thus, it does not hide data patterns well. In some senses, it doesn't provide serious message confidentiality, and it is not recommended for use in cryptographic protocols at all.

A striking example of the degree to which ECB can leave plaintext data patterns in the ciphertext can be seen when ECB mode is used to encrypt a bitmap image which uses large areas of uniform colour. While the colour of each individual pixel is encrypted, the overall image may still be discerned as the pattern of identically coloured pixels in the original remains in the encrypted version.

ECB mode can also make protocols without integrity protection even more susceptible to replay attacks, since each block gets decrypted in exactly the same way.

Cipher Block Chaining (CBC)

| CBC | |

|---|---|

| Cipher Block Chaining | |

| Encryption parallelizable: | No |

| Decryption parallelizable: | Yes |

| Random read access: | Yes |

Ehrsam, Meyer, Smith and Tuchman invented the Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode of operation in 1976.[10] In CBC mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted. This way, each ciphertext block depends on all plaintext blocks processed up to that point. To make each message unique, an initialization vector must be used in the first block.

If the first block has index 1, the mathematical formula for CBC encryption is

while the mathematical formula for CBC decryption is

CBC has been the most commonly used mode of operation. Its main drawbacks are that encryption is sequential (i.e., it cannot be parallelized), and that the message must be padded to a multiple of the cipher block size. One way to handle this last issue is through the method known as ciphertext stealing. Note that a one-bit change in a plaintext or IV affects all following ciphertext blocks.

Decrypting with the incorrect IV causes the first block of plaintext to be corrupt but subsequent plaintext blocks will be correct. This is because each block is XORed with the ciphertext of the previous block, not the plaintext, so one does not need to decrypt the previous block before using it as the IV for the decryption of the current one. This means that a plaintext block can be recovered from two adjacent blocks of ciphertext. As a consequence, decryption can be parallelized. Note that a one-bit change to the ciphertext causes complete corruption of the corresponding block of plaintext, and inverts the corresponding bit in the following block of plaintext, but the rest of the blocks remain intact. This peculiarity is exploited in different padding oracle attacks, such as POODLE.

Explicit Initialization Vectors[11] takes advantage of this property by prepending a single random block to the plaintext. Encryption is done as normal, except the IV does not need to be communicated to the decryption routine. Whatever IV decryption uses, only the random block is "corrupted". It can be safely discarded and the rest of the decryption is the original plaintext.

Propagating Cipher Block Chaining (PCBC)

| PCBC | |

|---|---|

| Propagating Cipher Block Chaining | |

| Encryption parallelizable: | No |

| Decryption parallelizable: | No |

| Random read access: | No |

The Propagating Cipher Block Chaining[12] or plaintext cipher-block chaining[13] mode was designed to cause small changes in the ciphertext to propagate indefinitely when decrypting, as well as when encrypting. In PCBC mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with both the previous plaintext block and the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted. As with CBC mode, an initialization vector is used in the first block.

Encryption and decryption algorithms are as follows:

PCBC is used in Kerberos v4 and WASTE, most notably, but otherwise is not common. On a message encrypted in PCBC mode, if two adjacent ciphertext blocks are exchanged, this does not affect the decryption of subsequent blocks.[14] For this reason, PCBC is not used in Kerberos v5.

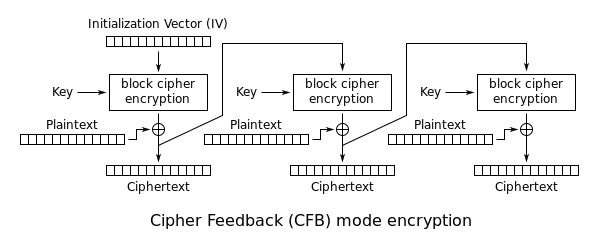

Cipher Feedback (CFB)

| CFB | |

|---|---|

| Cipher Feedback | |

| Encryption parallelizable: | No |

| Decryption parallelizable: | Yes |

| Random read access: | Yes |

The Cipher Feedback (CFB) mode, a close relative of CBC, makes a block cipher into a self-synchronizing stream cipher. Operation is very similar; in particular, CFB decryption is almost identical to CBC encryption performed in reverse:

By definition of self-synchronising cipher, if part of the ciphertext is lost (e.g. due to transmission errors), then the receiver will lose only some part of the original message (garbled content), and should be able to continue to correctly decrypt the rest of the blocks after processing some amount of input data. This simplest way of using CFB described above is not any more self-synchronizing than other cipher modes like CBC. Only if a whole blocksize of ciphertext is lost, both CBC and CFB will synchronize, but losing only a single byte or bit will permanently throw off decryption. To be able to synchronize after the loss of only a single byte or bit, a single byte or bit must be encrypted at a time. CFB can be used this way when combined with a shift register as the input for the block cipher.

To use CFB to make a self-synchronizing stream cipher that will synchronize for any multiple of x bits lost, start by initializing a shift register the size of the block size with the initialization vector. This is encrypted with the block cipher, and the highest x bits of the result are XOR'ed with x bits of the plaintext to produce x bits of ciphertext. These x bits of output are shifted into the shift register, and the process repeats with the next x bits of plaintext. Decryption is similar, start with the initialization vector, encrypt, and XOR the high bits of the result with x bits of the ciphertext to produce x bits of plaintext. Then shift the x bits of the ciphertext into the shift register. This way of proceeding is known as CFB-8 or CFB-1 (according to the size of the shifting).[15]

In notation, where Si is the ith state of the shift register, a << x is a shifted up x bits, head(a, x) is the x highest bits of a and n is number of bits of IV:

If x bits are lost from the ciphertext, the cipher will output incorrect plaintext until the shift register once again equals a state it held while encrypting, at which point the cipher has resynchronized. This will result in at most one blocksize of output being garbled.

Like CBC mode, changes in the plaintext propagate forever in the ciphertext, and encryption cannot be parallelized. Also like CBC, decryption can be parallelized. When decrypting, a one-bit change in the ciphertext affects two plaintext blocks: a one-bit change in the corresponding plaintext block, and complete corruption of the following plaintext block. Later plaintext blocks are decrypted normally.

CFB shares two advantages over CBC mode with the stream cipher modes OFB and CTR: the block cipher is only ever used in the encrypting direction, and the message does not need to be padded to a multiple of the cipher block size (though ciphertext stealing can also be used to make padding unnecessary).

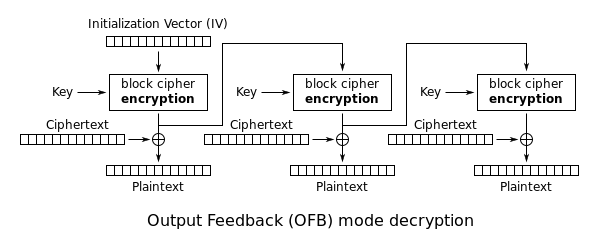

Output Feedback (OFB)

| OFB | |

|---|---|

| Output Feedback | |

| Encryption parallelizable: | No |

| Decryption parallelizable: | No |

| Random read access: | No |

The Output Feedback (OFB) mode makes a block cipher into a synchronous stream cipher. It generates keystream blocks, which are then XORed with the plaintext blocks to get the ciphertext. Just as with other stream ciphers, flipping a bit in the ciphertext produces a flipped bit in the plaintext at the same location. This property allows many error correcting codes to function normally even when applied before encryption.

Because of the symmetry of the XOR operation, encryption and decryption are exactly the same:

Each output feedback block cipher operation depends on all previous ones, and so cannot be performed in parallel. However, because the plaintext or ciphertext is only used for the final XOR, the block cipher operations may be performed in advance, allowing the final step to be performed in parallel once the plaintext or ciphertext is available.

It is possible to obtain an OFB mode keystream by using CBC mode with a constant string of zeroes as input. This can be useful, because it allows the usage of fast hardware implementations of CBC mode for OFB mode encryption.

Using OFB mode with a partial block as feedback like CFB mode reduces the average cycle length by a factor of or more. A mathematical model proposed by Davies and Parkin and substantiated by experimental results showed that only with full feedback an average cycle length near to the obtainable maximum can be achieved. For this reason, support for truncated feedback was removed from the specification of OFB.[16][17]

Counter (CTR)

| CTR | |

|---|---|

| Counter | |

| Encryption parallelizable: | Yes |

| Decryption parallelizable: | Yes |

| Random read access: | Yes |

- Note: CTR mode (CM) is also known as integer counter mode (ICM) and segmented integer counter (SIC) mode

Like OFB, Counter mode turns a block cipher into a stream cipher. It generates the next keystream block by encrypting successive values of a "counter". The counter can be any function which produces a sequence which is guaranteed not to repeat for a long time, although an actual increment-by-one counter is the simplest and most popular. The usage of a simple deterministic input function used to be controversial; critics argued that "deliberately exposing a cryptosystem to a known systematic input represents an unnecessary risk."[18] However, today CTR mode is widely accepted and any problems are considered a weakness of the underlying block cipher, which is expected to be secure regardless of systemic bias in its input.[19] Along with CBC, CTR mode is one of two block cipher modes recommended by Niels Ferguson and Bruce Schneier.[20]

CTR mode was introduced by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman in 1979.[21]

CTR mode has similar characteristics to OFB, but also allows a random access property during decryption. CTR mode is well suited to operate on a multi-processor machine where blocks can be encrypted in parallel. Furthermore, it does not suffer from the short-cycle problem that can affect OFB.[22]

If the IV/nonce is random, then they can be combined together with the counter using any lossless operation (concatenation, addition, or XOR) to produce the actual unique counter block for encryption. In case of a non-random nonce (such as a packet counter), the nonce and counter should be concatenated (e.g., storing the nonce in the upper 64 bits and the counter in the lower 64 bits of a 128-bit counter block). Simply adding or XORing the nonce and counter into a single value would break the security under a chosen-plaintext attack in many cases, since the attacker may be able to manipulate the entire IV-counter pair to cause a collision. Once an attacker controls the IV-counter pair and plaintext, XOR of the ciphertext with the known plaintext would yield a value that, when XORed with the ciphertext of the other block sharing the same IV-counter pair, would decrypt that block.[23]

Note that the nonce in this diagram is equivalent to the initialization vector (IV) in the other diagrams. However, if the offset/location information is corrupt, it will be impossible to partially recover such data due to the dependence on byte offset.

Error propagation

Before the widespread use of message authentication codes and authenticated encryption, it was common to discuss the "error propagation" properties as a selection criterion for a mode of operation. It might be observed, for example, that a one-block error in the transmitted ciphertext would result in a one-block error in the reconstructed plaintext for ECB mode encryption, while in CBC mode such an error would affect two blocks.

Some felt that such resilience was desirable in the face of random errors (e.g., line noise), while others argued that error correcting increased the scope for attackers to maliciously tamper with a message.

However, when proper integrity protection is used, such an error will result (with high probability) in the entire message being rejected. If resistance to random error is desirable, error-correcting codes should be applied to the ciphertext before transmission.

Authenticated encryption

A number of modes of operation have been designed to combine secrecy and authentication in a single cryptographic primitive. Examples of such modes are XCBC,[24] IACBC, IAPM,[25] OCB, EAX, CWC, CCM, and GCM. Authenticated encryption modes are classified as single pass modes or double pass modes. Unfortunately for the cryptographic user community, many of the single pass authenticated encryption algorithms (such as OCB mode) are patent encumbered.

In addition, some modes also allow for the authentication of unencrypted associated data, and these are called AEAD (Authenticated-Encryption with Associated-Data) schemes. For example, EAX mode is a double pass AEAD scheme while OCB mode is single pass.

Other modes and other cryptographic primitives

Many more modes of operation for block ciphers have been suggested. Some have been accepted, fully described (even standardized), and are in use. Others have been found insecure, and should never be used. Still others don't categorize as confidentiality, authenticity, or authenticated encryption - for example key feedback mode and Davies-Meyer hashing.

NIST maintains a list of proposed modes for block ciphers at Modes Development.[15][26]

Disk encryption often uses special purpose modes specifically designed for the application. Tweakable narrow-block encryption modes (LRW, XEX, and XTS) and wide-block encryption modes (CMC and EME) are designed to securely encrypt sectors of a disk. (See disk encryption theory)

Block ciphers can also be used in other cryptographic protocols. They are generally used in modes of operation similar to the block modes described here. As with all protocols, to be cryptographically secure, care must be taken to build them correctly.

There are several schemes which use a block cipher to build a cryptographic hash function. See one-way compression function for descriptions of several such methods.

Cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators (CSPRNGs) can also be built using block ciphers.

Message authentication codes (MACs) are often built from block ciphers. CBC-MAC, OMAC and PMAC are examples.

See also

References

- ^ NIST Computer Security Division's (CSD) Security Technology Group (STG) (2013). "Block cipher modes". Cryptographic Toolkit. NIST. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ a b

Cryptography Engineering: Design Principles and Practical Applications. Ferguson, N., Schneier, B. and Kohno, T. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 2010. pp. 63, 64. ISBN 978-0-470-47424-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ NIST Computer Security Division's (CSD) Security Technology Group (STG) (2013). "Proposed modes". Cryptographic Toolkit. NIST. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^

Handbook of Applied Cryptography. CRC Press. 1996. pp. 228–233. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c

"ISO/IEC 10116:2006 - Information technology -- Security techniques -- Modes of operation for an n-bit block cipher". ISO Standards catalogue. 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c

"A Novel Structure with Dynamic Operation Mode for Symmetric-Key Block Ciphers" (PDF). International Journal of Network Security & Its Applications (IJNSA). 5 (1): 19. January 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ NIST Computer Security Division's (CSD) Security Technology Group (STG) (2013). "Current modes". Cryptographic Toolkit. NIST. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ "Stream Cipher Reuse: A Graphic Example". Cryptosmith LLC. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ B. Moeller (May 20, 2004), Security of CBC Ciphersuites in SSL/TLS: Problems and Countermeasures

- ^ William F. Ehrsam, Carl H. W. Meyer, John L. Smith, Walter L. Tuchman, "Message verification and transmission error detection by block chaining", US Patent 4074066, 1976

- ^ "The Transport Layer Security (TLS) Protocol Version 1.1". p. 20. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ http://www.iks-jena.de/mitarb/lutz/security/cryptfaq/q84.html

- ^ Kaufman, C.; Perlman, R.; Speciner, M. (2002). Network Security (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 319. ISBN 0130460192.

- ^ Kohl, J. (1990). "The Use of Encryption in Kerberos for Network Authentication". Proceedings, Crypto '89. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 0387973176.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b NIST: Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation

- ^ Davies, D. W.; Parkin, G. I. P. (1983). "The average cycle size of the key stream in output feedback encipherment". Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of CRYPTO 82. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 263–282. ISBN 0306413663.

- ^ http://www.crypto.rub.de/its_seminar_ws0809.html

- ^ Jueneman, Robert R. (1983). "Analysis of certain aspects of output feedback mode". Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of CRYPTO 82. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 99–127. ISBN 0306413663.

- ^ Helger Lipmaa, Phillip Rogaway, and David Wagner. Comments to NIST concerning AES modes of operation: CTR-mode encryption. 2000

- ^ Niels Ferguson, Bruce Schneier, Tadayoshi Kohno, Cryptography Engineering, page 71, 2010

- ^ Lipmaa, Helger; Wagner, David; Rogaway, Phillip. "Comments to NIST concerning AES Modes of Operations: CTR-Mode Encryption" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.quadibloc.com/crypto/co040601.htm

- ^ https://class.coursera.org/crypto-010/lecture/21

- ^ Virgil D. Gligor, Pompiliu Donescu, "Fast Encryption and Authentication: XCBC Encryption and XECB Authentication Modes". Proc. Fast Software Encryption, 2001: 92-108.

- ^ Charanjit S. Jutla, "Encryption Modes with Almost Free Message Integrity", Proc. Eurocrypt 2001, LNCS 2045, May 2001.

- ^ NIST: Modes Development