Bone marrow

| Bone marrow | |

|---|---|

A simplified illustration of cells in bone marrow | |

| Details | |

| System | Immune system[1](Lymphatic system) |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Medulla ossium |

| MeSH | D001853 |

| TA98 | A13.1.01.001 |

| TA2 | 388 |

| FMA | 9608 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Bone marrow is the flexible tissue in the interior of bones. In humans, red blood cells are produced by cores of bone marrow in the heads of long bones in a process known as hematopoiesis.[2] On average, bone marrow constitutes 4% of the total body mass of humans; in an adult having 65 kilograms of mass (143 lbs), bone marrow typically accounts for approximately 2.6 kilograms (5.7 lb). The hematopoietic component of bone marrow produces approximately 500 billion blood cells per day, which use the bone marrow vasculature as a conduit to the body's systemic circulation.[3] Bone marrow is also a key component of the lymphatic system, producing the lymphocytes that support the body's immune system.[4]

Bone marrow transplants can be conducted to treat severe diseases of the bone marrow, including certain forms of cancer such as leukemia. Additionally, bone marrow stem cells have been successfully transformed into functional neural cells,[5] and can also potentially be used to treat illnesses such as inflammatory bowel disease.[6]

Structure

Types of bone marrow

The two types of bone marrow are "red marrow" (Template:Lang-la), which consists mainly of hematopoietic tissue, and "yellow marrow" (Template:Lang-la), which is mainly made up of fat cells. Red blood cells, platelets, and most white blood cells arise in red marrow. Both types of bone marrow contain numerous blood vessels and capillaries. At birth, all bone marrow is red. With age, more and more of it is converted to the yellow type; only around half of adult bone marrow is red. Red marrow is found mainly in the flat bones, such as the pelvis, sternum, cranium, ribs, vertebrae and scapulae, and in the cancellous ("spongy") material at the epiphyseal ends of long bones such as the femur and humerus. Yellow marrow is found in the medullary cavity, the hollow interior of the middle portion of short bones. In cases of severe blood loss, the body can convert yellow marrow back to red marrow to increase blood cell production.

Stroma

The stroma of the bone marrow is all tissue not directly involved in the marrow's primary function of hematopoiesis.[2] Yellow bone marrow makes up the majority of bone marrow stroma, in addition to smaller concentrations of stromal cells located in the red bone marrow. Though not as active as parenchymal red marrow, stroma is indirectly involved in hematopoiesis, since it provides the hematopoietic microenvironment that facilitates hematopoiesis by the parenchymal cells. For instance, they generate colony stimulating factors, which have a significant effect on hematopoiesis. Cell types that constitute the bone marrow stroma include:

- fibroblasts (reticular connective tissue)

- macrophages, which contribute especially to red blood cell production, as they deliver iron for hemoglobin production.

- adipocytes (fat cells)

- osteoblasts (synthesize bone)

- osteoclasts (resorb bone)

- endothelial cells, which form the sinusoids. These derive from endothelial stem cells, which are also present in the bone marrow.[7]

Cellular components

| Group | Cell type | Average fraction |

Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myelopoietic cells |

Myeloblasts | 0.9% | 0.2–1.5 |

| Promyelocytes | 3.3% | 2.1–4.1 | |

| Neutrophilic myelocytes | 12.7% | 8.2–15.7 | |

| Eosinophilic myelocytes | 0.8% | 0.2–1.3 | |

| Neutrophilic metamyelocytes | 15.9% | 9.6–24.6 | |

| Eosinophilic metamyelocytes | 1.2% | 0.4–2.2 | |

| Neutrophilic band cells | 12.4% | 9.5–15.3 | |

| Eosinophilic band cells | 0.9% | 0.2–2.4 | |

| Segmented neutrophils | 7.4% | 6.0–12.0 | |

| Segmented eosinophils | 0.5% | 0.0–1.3 | |

| Segmented basophils and mast cells | 0.1% | 0.0–0.2 | |

| Erythropoietic cells |

Pronormoblasts | 0.6% | 0.2–1.3 |

| Basophilic normoblasts | 1.4% | 0.5–2.4 | |

| Polychromatic normoblasts | 21.6% | 17.9–29.2 | |

| Orthochromatic normoblast | 2.0% | 0.4–4.6 | |

| Other cell types |

Megakaryocytes | < 0.1% | 0.0-0.4 |

| Plasma cells | 1.3% | 0.4-3.9 | |

| Reticular cells | 0.3% | 0.0-0.9 | |

| Lymphocytes | 16.2% | 11.1-23.2 | |

| Monocytes | 0.3% | 0.0-0.8 |

In addition, the bone marrow contains hematopoietic stem cells, which give rise to the three classes of blood cells that are found in the circulation: white blood cells (leukocytes), red blood cells (erythrocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes).[7]

Function

Mesenchymal stem cells

The bone marrow stroma contains mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs),[7] also known as marrow stromal cells. These are multipotent stem cells that can differentiate into a variety of cell types. MSCs have been shown to differentiate, in vitro or in vivo, into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, myocytes, adipocytes and beta-pancreatic islets cells.

Bone marrow barrier

The blood vessels of the bone marrow constitute a barrier, inhibiting immature blood cells from leaving the marrow. Only mature blood cells contain the membrane proteins, such as aquaporin and glycophorin, that are required to attach to and pass the blood vessel endothelium.[9] Hematopoietic stem cells may also cross the bone marrow barrier, and may thus be harvested from blood.

Lymphatic role

The red bone marrow is a key element of the lymphatic system, being one of the primary lymphoid organs that generate lymphocytes from immature hematopoietic progenitor cells.[4] The bone marrow and thymus constitute the primary lymphoid tissues involved in the production and early selection of lymphocytes. Furthermore, bone marrow performs a valve-like function to prevent the backflow of lymphatic fluid in the lymphatic system.

Compartmentalization

Biological compartmentalization is evident within the bone marrow, in that certain cell types tend to aggregate in specific areas. For instance, erythrocytes, macrophages, and their precursors tend to gather around blood vessels, while granulocytes gather at the borders of the bone marrow.[7]

Society and culture

Animal bone marrow has been used in cuisine worldwide for millennia, such as the famed Milanese Ossobuco. [citation needed]

Clinical significance

Disease

The normal bone marrow architecture can be damaged or displaced by aplastic anemia, malignancies such as multiple myeloma, or infections such as tuberculosis, leading to a decrease in the production of blood cells and blood platelets. The bone marrow can also be affected by various forms of leukemia, which attacks its hematologic progenitor cells.[10] Furthermore, exposure to radiation or chemotherapy will kill many of the rapidly dividing cells of the bone marrow, and will therefore result in a depressed immune system. Many of the symptoms of radiation poisoning are due to damage sustained by the bone marrow cells.

To diagnose diseases involving the bone marrow, a bone marrow aspiration is sometimes performed. This typically involves using a hollow needle to acquire a sample of red bone marrow from the crest of the ilium under general or local anesthesia.[11]

Imaging

On CT and plain film, marrow change can be seen indirectly by assessing change to the adjacent ossified bone. Assessment with MRI is usually more sensitive and specific for pathology, particularly for hematologic malignancies like leukemia and lymphoma. These are difficult to distinguish from the red marrow hyperplasia of hematopoiesis, as can occur with tobacco smoking, chronically anemic disease states like sickle cell anemia or beta thalassemia, medications such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factors, or during recovery from chronic nutritional anemias or therapeutic bone marrow suppression.[12] On MRI, the marrow signal is not supposed to be brighter than the adjacent intervertebral disc on T1 weighted images, either in the coronal or sagittal plane, where they can be assessed immediately adjacent to one another.[13] Fatty marrow change, the inverse of red marrow hyperplasia, can occur with normal aging,[14] though it can also be seen with certain treatments such as radiation therapy. Diffuse marrow T1 hypointensity without contrast enhancement or cortical discontinuity suggests red marrow conversion or myelofibrosis. Falsely normal marrow on T1 can be seen with diffuse multiple myeloma or leukemic infiltration when the water to fat ratio is not sufficiently altered, as may be seen with lower grade tumors or earlier in the disease process.[15]

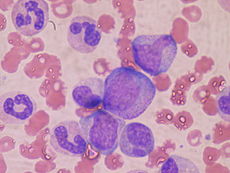

Histology

Bone marrow examination is the pathologic analysis of samples of bone marrow obtained via biopsy and bone marrow aspiration. Bone marrow examination is used in the diagnosis of a number of conditions, including leukemia, multiple myeloma, anemia, and pancytopenia. The bone marrow produces the cellular elements of the blood, including platelets, red blood cells and white blood cells. While much information can be gleaned by testing the blood itself (drawn from a vein by phlebotomy), it is sometimes necessary to examine the source of the blood cells in the bone marrow to obtain more information on hematopoiesis; this is the role of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

The ratio between myeloid series and erythroid cells is relevant to bone marrow function, and also to diseases of the bone marrow and peripheral blood, such as leukemia and anemia. The normal myeloid-to-erythroid ratio is around 3:1; this ratio may increase in myelogenous leukemias, decrease in polycythemias, and reverse in cases of thalassemia.[16]

Donation and transplantation

In a bone marrow transplant, hematopoietic stem cells are removed from a person and infused into another person (allogenic) or into the same person at a later time (autologous). If the donor and recipient are compatible, these infused cells will then travel to the bone marrow and initiate blood cell production. Transplantation from one person to another is conducted for the treatment of severe bone marrow diseases, such as congenital defects, autoimmune diseases or malignancies. The patient's own marrow is first killed off with drugs or radiation, and then the new stem cells are introduced. Before radiation therapy or chemotherapy in cases of cancer, some of the patient's hematopoietic stem cells are sometimes harvested and later infused back when the therapy is finished to restore the immune system.[17]

Bone marrow stem cells can be induced to become neural cells to treat neurological illnesses,[5] and can also potentially be used for the treatment of other illnesses, such as inflammatory bowel disease.[6] In 2013, following a clinical trial, scientists proposed that bone marrow transplantation could be used to treat HIV in conjunction with antiretroviral drugs;[18][19] however, it was later found that HIV remained in the bodies of the test subjects.[20]

Harvesting

The stem cells are typically harvested directly from the red marrow in the iliac crest, often under general anesthesia. The procedure is minimally invasive and does not require stitches afterwards. Depending on the donor's health and reaction to the procedure, the actual harvesting can be an outpatient procedure, or can require 1–2 days of recovery in the hospital.[21]

Another option is to administer certain drugs that stimulate the release of stem cells from the bone marrow into circulating blood.[22] An intravenous catheter is inserted into the donor's arm, and the stem cells are then filtered out of the blood. This procedure is similar to that used in blood or platelet donation. In adults, bone marrow may also be taken from the sternum, while the tibia is often used when taking samples from infants.[11] In newborns, stem cells may be retrieved from the umbilical cord.[23]

Fossil record

The earliest fossilised evidence of bone marrow was discovered in 2014 in Eusthenopteron, a lobe-finned fish which lived during the Devonian period approximately 370 million years ago.[24] Scientists from Uppsala University and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility used X-ray synchrotron microtomography to study the fossilised interior of the skeleton's humerus, finding organised tubular structures akin to modern vertebrate bone marrow.[24] Eusthenopteron is closely related to the early tetrapods, which ultimately evolved into the land-dwelling mammals and lizards of the present day.[24]

See also

- National Marrow Donor Program, a nonprofit organization that operates a registry of volunteer hematopoietic cell donors and umbilical cord blood units in the United States

- Gift of Life Marrow Registry, an American bone marrow transplantation registry

References

- ^ Schmidt, Richard F.; Lang, Florian; Heckmann, Manfred (30 November 2010). "What are the organs of the immune system?". © IQWiG (Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care): 3/7.

- ^ a b Birbrair, Alexander; Frenette, Paul S. (1 March 2016). "Niche heterogeneity in the bone marrow". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/nyas.13016. ISSN 1749-6632.

- ^ Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Tandon, N.; Godier, A.; Maidhof, R.; Marsano, A.; Martens, T. P.; Radisic, M. (2010). "Challenges in Cardiac Tissue Engineering". Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 16 (2): 169–187. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0352.

- ^ a b The Lymphatic System. Allonhealth.com. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Antibody Transforms Stem Cells Directly Into Brain Cells". Science Daily. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Research Supports Promise of Cell Therapy for Bowel Disease". Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d Raphael Rubin; David S. Strayer (2007). Rubin's Pathology: Clinicopathologic Foundations of Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 90. ISBN 0-7817-9516-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Appendix A:IV in Wintrobe's clinical hematology (9th edition). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger (1993).

- ^ "The Red Cell Membrane: structure and pathologies" (PDF). Australian Centre for Blood Diseases/Monash University. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell". Nature. 1997. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy". Lab Tests Online UK. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Poulton, TB; Murphy, WD; Duerk, JL; Chapek, CC; Feiglin, DH (December 1993). "Bone marrow reconversion in adults who are smokers: MR Imaging findings". AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 161 (6): 1217–21. doi:10.2214/ajr.161.6.8249729. PMID 8249729.

- ^ Zajick DC, Jr; Morrison, WB; Schweitzer, ME; Parellada, JA; Carrino, JA (November 2005). "Benign and malignant processes: normal values and differentiation with chemical shift MR imaging in vertebral marrow". Radiology. 237 (2): 590–6. doi:10.1148/radiol.2372040990. PMID 16244268.

- ^ Shah, LM; Hanrahan, CJ (December 2011). "MRI of spinal bone marrow: part I, techniques and normal age-related appearances". AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 197 (6): 1298–308. doi:10.2214/ajr.11.7005. PMID 22109283.

- ^ Vande Berg, BC; Lecouvet, FE; Galant, C; Maldague, BE; Malghem, J (July 2005). "Normal variants and frequent marrow alterations that simulate bone marrow lesions at MR imaging". Radiologic clinics of North America. 43 (4): 761–70, ix. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2005.01.007. PMID 15893536.

- ^ "Definition: 'M:E Ratio'". Stedman's Medical Dictionary via MediLexicon.com. 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Bone marrow transplantation". UpToDate.com. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Bone marrow 'frees men of HIV drugs'". BBC. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "Stem-Cell Transplants Erase HIV In Two Men". PopSci. 3 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "HIV Returns in Two Men Thought 'Cured' by Bone Marrow Transplants". RH Reality Check. 10 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ National Marrow Donor Program Donor Guide Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Marrow.org. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ Bone marrow donation: What to expect when you donate. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ McGuckin, C. P.; Forraz, N.; Baradez, M. -O.; Navran, S.; Zhao, J.; Urban, R.; Tilton, R.; Denner, L. (2005). "Production of stem cells with embryonic characteristics from human umbilical cord blood". Cell Proliferation. 38 (4): 245–255. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00346.x. PMID 16098183.

- ^ a b c Sanchez S., Tafforeau P. and Ahlberg P. E. (2014) "The humerus of Eusthenopteron: a puzzling organization presaging the establishment of tetrapod limb bone marrow". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281 (1782): 20140299. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0299

External links

Further reading

- Nature Bone Marrow Transplantation (Nature Publishing Group) – specialist scientific journal with articles on bone marrow biology and clinical uses.

- Cooper, B (2011). "The origins of bone marrow as the seedbed of our blood: from antiquity to the time of Osler" (PDF). Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 24 (2): 115–8. PMC 3069519. PMID 21566758.

- Wang J, Yu L, Jiang C, Chen M, Ou C, Wang J (2013). "Bone marrow mononuclear cells exert long-term neuroprotection in a rat model of ischemic stroke by promoting arteriogenesis and angiogenesis". Brain Behav Immun. 34: 56–66. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.010. PMC 3795857. PMID 23891963.

- Wang J, Yu L, Jiang C, Fu X, Liu X, Wang M, Ou C, Cui X, Zhou C, Wang J (2015). "Cerebral ischemia increases bone marrow CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in mice via signals from sympathetic nervous system". Brain Behav Immun. 43: 172–83. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.022. PMC 4258426. PMID 25110149.

- Wang J, Liu X, Lu H, Jiang C, Cui X, Yu L, Fu X, Li Q, Wang J (2015). "CXCR4(+)CD45(-) BMMNC subpopulation is superior to unfractionated BMMNCs for protection after ischemic stroke in mice". Brain Behav Immun. 45: 98–108. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2014.12.015. PMC 4342301. PMID 25526817.